In March 2011, protests broke out in Syria against the dictator Bashar al-Assad. Assad turned the full power of the military against the ensuing revolutionary movement; yet for some time, it appeared possible that it might topple his government. Then Vladimir Putin stepped in, enabling Assad to stay in power at a tremendous cost in human lives and securing a foothold for Russian power in the region. In the following text, a collective of Syrian exiles and their comrades think through how their experiences in the Syrian Revolution can inform efforts to support the resistance to the invasion in Ukraine and the anti-war movement in Russia.

So much attention has been focused on Ukraine and Russia this past month that it is easy to lose track of the global context of these events. The following text offers a valuable reflection on imperialism, international solidarity, and understanding the nuances of complex and contradictory struggles.

Portraits of Putin and Assad look on as armed soldiers patrol the ruins of Syria.

Ten Lessons from Syria

We know it can be difficult to position yourself at a time like this. Between the ideological unanimity of the mainstream media and voices that unscrupulously relay Kremlin propaganda, it can be hard to know who to listen to. Between a NATO with dirty hands and a villainous Russian regime, we no longer know who to fight, who to support.

As participants in and friends of the Syrian revolution, we want to defend a third option, offering a point of view based on the lessons of more than ten years of uprising and war in Syria.

Let us make this clear from the beginning: today, we still defend the revolt in Syria in all the ways that it was a popular, democratic, and emancipatory uprising, especially the coordination committees and the local councils of the revolution. While many have forgotten all this, we maintain that neither Bashar al-Assad’s atrocities and propaganda nor those of the jihadists can silence this voice.

In what follows, we do not intend to compare what is happening in Syria and Ukraine. If these two wars both began with a revolution, and if one of the aggressors is the same, the situations remain very different. Rather, drawing on what we have learned from the revolution in Syria and then from the war that followed, we hope to offer some starting points to assist those who sincerely espouse emancipatory principles in figuring out how to take a stand.

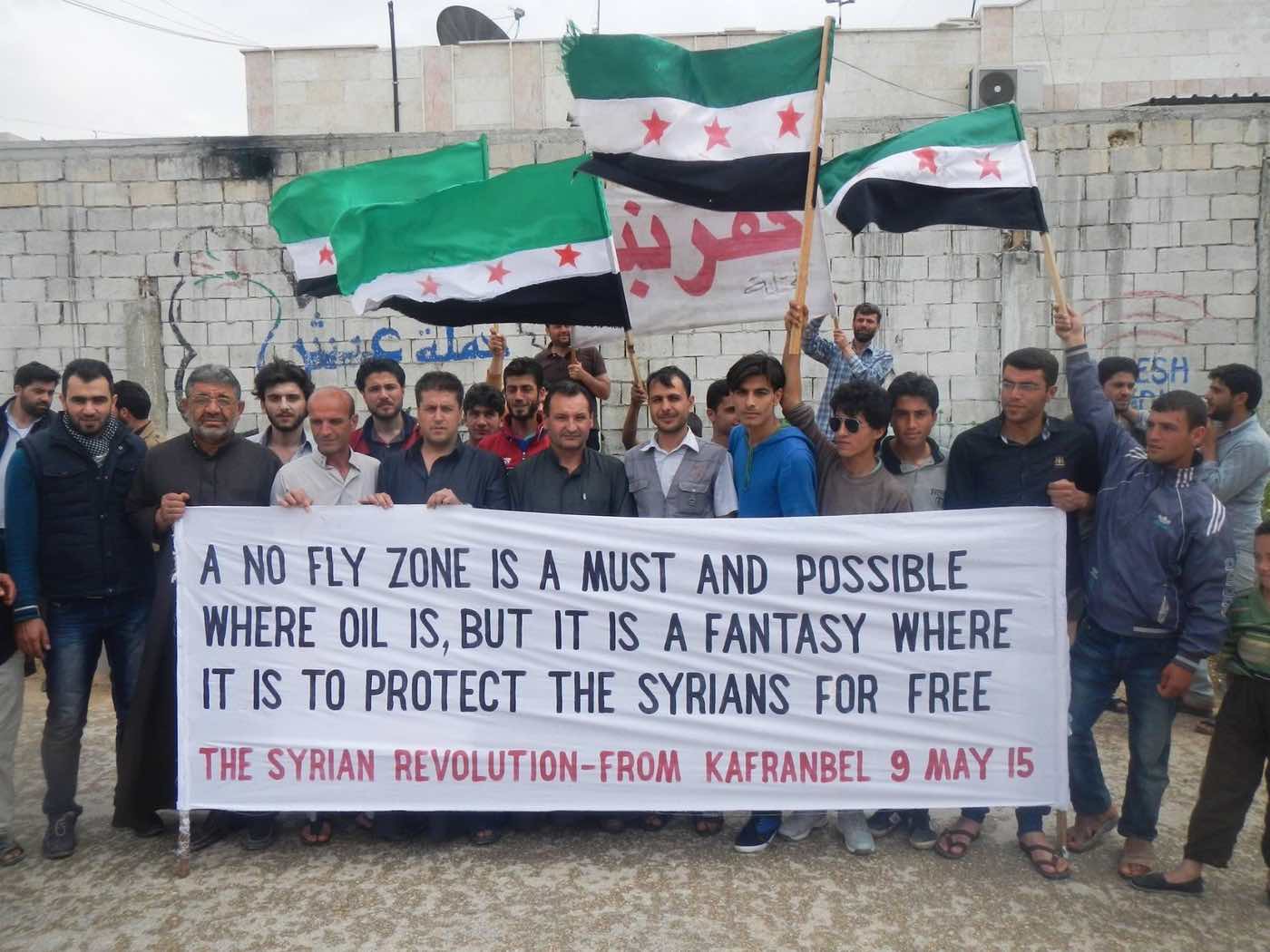

A banner in the Syrian town of Kafranbel. For a note on the flags displayed in this photograph, consult the appendix, below.

1. Listen to the voices of those immediately impacted by the events.

Rather than experts in geopolitics, we should listen to the voices of those who have lived through the revolution in 2014 and lived through the war; we should listen to those who have suffered under Putin’s rule in Russia and elsewhere for twenty years. We invite you to favor the voices of people and organizations that defend the principles of direct democracy, feminism, and egalitarianism from that context. Understanding their position in Ukraine and their demands to those outside it will help you to arrive at an informed opinion of your own.

Taking this approach to Syria would have elevated—and perhaps supported—the impressive and promising experiments in self-organization that flourished across the country. Moreover, listening to the voices coming from Ukraine reminds us that all these tensions started with the Maidan uprising. However imperfect or “impure” it may be, let’s not make the mistake of reducing the popular Ukrainian uprising to a conflict of interests between great powers, the way some people intentionally did to obscure the Syrian revolution.

2: Beware of over-the-counter geopolitics.

Certainly, it’s desirable to understand the economic, diplomatic, and military interests of the great powers; yet contenting yourself with an abstract geopolitical framing of the situation can leave you with an abstract, disconnected understanding of the terrain. This way of understanding tends to conceal the ordinary protagonists of the conflict, those who resemble us, those with whom we can identify. Above all, let’s not forget: what will happen is that people will suffer because of the choices of rulers who see the world as a chessboard, as a reservoir of resources to be plundered. This is the way that oppressors see the world. It should never be adopted by peoples, who should focus on building bridges between them, on finding common interests.

This does not mean that we should neglect strategy, but it means strategizing on our own terms, at a scale on which we can take action ourselves—not to debate about whether to move tank divisions or cut gas imports. See our concrete proposals at the end of the article for more.

3: Do not accept any distinction between “good” and “bad” exiles.

Let’s be clear—though hardly ideal, the reception of Syrian refugees in Europe was often more welcoming than the reception offered to refugees from sub-Saharan Africa, for example. Images of Black refugees turned away at the Ukraine-Poland border and comments in the corporate media privileging the arrival of “high quality” Ukrainian refugees over Syrian barbarians are proof of an increasingly uninhibited European racism. We defend an unconditional welcome for Ukrainians fleeing the horrors of war, but we refuse any hierarchy between refugees.

4: Be wary of the corporate media.

If, as in Syria, they pretend to espouse a humanist and progressive agenda, most of these outlets tend to limit themselves to a victimizing and depoliticizing portrayal of the Ukrainians on the ground and in exile. They will only be given the opportunity to talk about individual cases, people fleeing, fear of bombs, and so on. This hinders viewers from understanding Ukrainians as full-fledged political actors capable of expressing opinions or political analysis regarding the situation in their own country. Moreover, such outlets tend to promote a crudely pro-Western position without nuance, historical depth, or inquiry into the driving interests of Western governments, which are presented as defenders of goodness, freedom, and an idealized liberal democracy.

Another photograph from Kafranbel.

5. Do not portray Western countries as the axis of good.

Even if they are not directly invading Ukraine, let us not be naïve about NATO and Western countries. We must refuse to present them as the defenders of the “free world.” Remember, the West has built its power on colonialism, imperialism, oppression, and the plundering of the wealth of hundreds of peoples around the world—and it continues all of these processes today.

To speak only of the 21st century, we do not forget the disasters inflicted by the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan. More recently, during the Arab revolutions of 2011, instead of supporting the democratic and progressive currents, the West was mainly concerned with maintaining its domination and its economic interests. At the same time, it continues to sell arms to and maintain privileged relations with Arab dictatorships and Gulf monarchies. With its intervention in Libya, France added the shameful lie of a war for economic reasons disguised as an effort to support the fight for democracy.

In addition to this international role, the situation within these countries continues to deteriorate as authoritarianism, surveillance, inequality, and above all racism continue to intensify.

Today, if we believe that Putin’s regime represents a greater threat to the self-determination of peoples, it is not because Western countries have suddenly become “nice,” but because Western powers no longer have quite as many means to maintain their domination and hegemony. And we remain suspicious of this hypothesis—because if Putin is defeated by Western countries, this will contribute to giving them more power.

Therefore, we advise Ukrainians not to count on the “international community” or the United Nations—which, as in Syria, are conspicuous in their hypocrisy and tend to lure people into believing in chimeras.

6: Fight all imperialisms!

“Campism” is the word we use to describe a doctrine from another era. During the Cold War, adherents of this dogma held that the most important thing was to support the USSR at all costs against capitalist and imperialist states. This doctrine persists today in the part of the radical left that supports Putin’s Russia in invading Ukraine or else relativizes the ongoing war. As they did in Syria, they use the pretext that the Russian or Syrian regimes embody the struggle against Western and Atlanticist [i.e., pro-NATO] imperialism. Unfortunately, this Manichean anti-imperialism, which is purely abstract, refuses to see imperialism in any actor other than the West.

However, it is necessary to acknowledge what the Russian, Chinese, and even Iranian regimes have been doing for years now. They have been extending their political and economic domination in certain regions by dispossessing the local populations of their self-determination. Let the campists use whatever word they like to describe this, if “imperialism” seems inadequate to them, but we will never accept any excusing of the inflicting of violence and domination on populations in the name of pseudo-theoretical precision.

Worse still, this position pushes this “left” to relay the propaganda of these regimes to the point of denying well-documented atrocities. They speak of a “coup d’etat” when they describe the Maidan uprising or deny the war crimes perpetrated by the Russian army in Syria. This left has gone so far as to deny the Assad regime’s use of sarin gas, relying on an (often understandable) distrust of mainstream media to spread these lies.

It’s a despicable and irresponsible attitude, considering that the rise of conspiracy theories never favors an emancipatory position but rather the extreme right and racism. In the case of the war in Ukraine, these imbecile anti-imperialists, some of whom nevertheless claim to be anti-fascist, are the circumstantial allies of a large part of the extreme right.

In Syria, enflamed with supremacist fantasies and dreams of a crusade against Islam, the far right already defended Putin and the Syrian regime for their alleged actions against jihadism—without ever understanding the responsibility that the Assad regime had for the rise of jihadists in Syria.

Another photograph from Kafranbel.

7: Do not ascribe equal responsibility to Ukraine and Russia.

In Ukraine, the identity of the attacker is known to everyone. If Putin’s offensive is in some ways a response to pressure from NATO, it is above all the continuation of an imperial and counter-revolutionary offensive. After invading Crimea, after having helped crush the uprisings in Syria (2015-2022), Belarus (2020), and Kazakhstan (2022), Vladimir Putin no longer tolerates this wind of protest—embodied by the toppling of the pro-Russian president in the Maidan uprising—within countries under his influence. He wishes to crush any emancipatory desire that could weaken his power.

In Syria too, there is no doubt as to who is directly responsible for the war. The Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad, by ordering the police to shoot, imprison, and torture the demonstrators from the first days of protest, unilaterally chose to start a war against the population. We would like it if those who defend freedom and equality would be unanimous in taking a stand against such dictators who wage wars against the people. We would have liked it if this had been the case already, in reference to Syria.

If we understand and join the call to end the war, we insist that we must do so without any ambiguity as to the identity of the aggressor. Neither in Ukraine nor in Syria nor anywhere else in the world can ordinary people be blamed for taking up arms to try to defend their own lives and those of their families.

More generally, we advise people who don’t know what a dictatorship is (even if Western countries are becoming more overtly authoritarian) or what it is like to be bombed to refrain from telling Ukrainians—as some have already told Syrians or Hong Kongers—not to ask for help from the West or not to want liberal or representative democracy as a minimum political system. Many of these people are already clear on the imperfections of these political systems—but their priority is not to maintain an irreproachable political position, but rather to survive the next day’s bombings, or not to end up in a country in which a careless word can land you twenty years in prison. Insisting on this sort of purist discourse demonstrates a determination to impose one’s theoretical analysis on a context that is not one’s own. This indicates a real disconnection from the terrain and a very Western sort of privilege.

Instead, let’s listen to the words of Ukrainian comrades who said, echoing Mikhail Bakunin, “We firmly believe that the most imperfect republic is a thousand times better than the most enlightened monarchy.”

A souvenir shop in Damascus, Syria.

8: Understand that Ukrainian society, as in Syria and France, is crossed by different currents.

We are familiar with the procedure in which a ruler designates a serious threat in order to scare off potential supporters. This includes the rhetoric about “Islamist terrorism” that Bashar al-Assad used from the first days of the revolution in Syria; likewise, today, the “Nazism” and “ultra-nationalism” Putin and his allies have brandished to justify their invasion of Ukraine.

If, on the one hand, we recognize that this propaganda is deliberately exaggerated and that we must not legitimize it at face value, on the other hand, our experience in Syria encourages us not to underestimate the reactionary currents within popular movements.

In Ukraine, Ukrainian nationalists, including fascists, played an important role in the Maidan protests and the ensuing war against Russia. Moreover, like the Azov Battalion, they profited from this experience and became a legitimate part of Ukraine’s regular army. However, this does not mean that the majority of Ukrainian society is ultra-nationalist or fascist. The far right won only 4% of the vote in the last elections; the Ukrainian, Jewish, and Russian-speaking president was elected by 73%.

In the revolt in Syria, the jihadists started out as marginal actors, but they took on increasing importance, thanks in part to external support, allowing them to impose themselves militarily to the detriment of the civil movement and the most progressive participants. Everywhere, the extreme right threatens the extension of democracies and social revolutions; this is the case in France today without a doubt. In France, this same extreme right attempted to impose itself during the Yellow Vests movement. If it was beaten then, it was beaten because of the presence of egalitarian positions and the determination of anti-authoritarian and anti-fascist activists, not by the tongue-wagging of pundits.

Take care that defending the popular resistance (in both Ukraine and in Russia) against the Russian invasion does not amount to being naïve about the political regime that emerged from Maidan, either. It cannot be said that the fall of Yanukovych resulted in a real extension of direct democracy or the development of the egalitarian society that we wish for Syria, Russia, France, and everywhere in the world. Using an expression that is well known to us, some Ukrainian activists call the post-Maidan a “stolen revolution.” In addition to granting an important place to the ultra-nationalists, the Ukrainian regime was reestablished by oligarchs and others who were concerned with defending their own economic and political interests and extending a capitalist and neoliberal model of inequality. Likewise, though our knowledge on this subject remains limited, it is difficult for us to believe that the Ukrainian regime has no responsibility in the exacerbation of tensions with the separatist regions in Donbas.

In Syria, the revolutionaries involved on the ground have every right to ferociously criticize the choices of the political opposition that is positioned in Istanbul. We still regret their choice not to take into account the legitimate claims of minorities like the Kurds.

A neoliberal regime and fascistic elements are ingredients found in all Western democracies. While these opponents of emancipation should not be underestimated, this is no reason not to champion popular resistance to an invasion. On the contrary, as we wish others had done during the Syrian revolution, we call on you to support the most progressive self-organized currents within the defense.

The Arabic caption reads “The time of masculinity and men.”

9. Support popular resistance in Ukraine and Russia.

As the Arab revolutions, the Yellow Vests, and the Maidan have proven, the uprisings of the 21st century will not be ideologically “pure.” While we understand that it is more comfortable and galvanizing to identify with powerful (and victorious) actors, we must not betray our fundamental principles. We invite the radical left to take off their old conceptual glasses to confront their theoretical positions with reality. These positions must be adjusted according to reality, not the other way around.

It is for these reasons that in Ukraine, we call for people to prioritize supporting initiatives that come from the base: the self-defense and self-organization initiatives that are currently flourishing. One can discover that often, people who organize themselves can in fact defend radical conceptions of democracy and social justice—even if they do not call themselves “leftist” or “progressive.”

Also, as many Russian activists have said, we believe that a popular uprising in Russia could help end the war, just as in 1905 and 1917. When we consider the extent of the repression in Russia since the war began—over ten thousand demonstrators imprisoned, media censorship, the blocking of social networks and perhaps soon the internet—it is impossible not to hope that a revolution could lead to fall of the regime. This would finally put a stop, once and for all, to Putin’s crimes in Russia, Ukraine, Syria, and elsewhere.

This is also the case for Syria where, following the internationalization of the conflict, far from resenting the Iranian, Russian, or Lebanese peoples, the uprisings of these peoples could make us believe again in the possibility that Bashar al-Assad will fall, as well.

Likewise, we want to see radical upheavals and radical extensions of democracy, justice, and equality in the United States, France, and every other country that bases its power on the oppression of other peoples or a part of its own population.

10. Build a new internationalism from below.

While we are radically opposed to all imperialisms and all modern forms of fascism, we believe that we cannot limit ourselves to anti-imperialist or anti-fascist postures alone. Even if they serve to explain many contexts, they also risk limiting the revolutionary struggle to a negative vision, reducing it to reactivity, to permanent resistance without a path forward.

We believe that it remains essential to make a positive and constructive proposal such as internationalism. This means linking uprisings and struggles for equality all around the world.

A third option exists in addition to NATO and Putin: internationalism from below. Today, a revolutionary internationalism must call on people everywhere to defend the popular resistance in Ukraine, just as it should call upon them to support the Syrian local councils, the resistance committees in Sudan, the territorial assemblies in Chile, the roundabouts of the Yellow Vests, and the Palestinian intifada.

Of course, we live in the shadow of a workers’ internationalism—supported by states, parties, unions and large organizations—that was able to carry weight in international conflicts in Spain in 1936 and, later, in Vietnam and Palestine in the 1960s and ’70s.

Today, everywhere in the world—from Syria to France, from Ukraine to the United States—we lack large-scale emancipatory forces endowed with substantial material bases. While we hope for the emergence, as seems to be happening in Chile, of new revolutionary organizations based on local self-organized initiatives, we defend an internationalism that supports popular uprisings and welcomes all exiles. In this effort, too, we are preparing the ground for a real return to internationalism, which, we hope, one day will once again represent an alternative path distinct from the models of Western capitalist democracies and capitalist authoritarianism, whether Russian or Chinese.

Such a conception of what we were doing, in Syria, would surely have helped the revolution to maintain a democratic and egalitarian color. Who knows, it might even have contributed to our achieving victory. Therefore, we are internationalists not only as a matter of ethical principle but also as a consequence of revolutionary strategy. We therefore defend the need to create links and alliances between self-organized forces working for the emancipation of all without distinction.

This is what we call internationalism from below, the internationalism of the peoples.

Proposed positions on the Russian invasion of Ukraine

- Express full support for Ukrainian popular resistance against the Russian invasion.

- Prioritize support for self-organized groups defending emancipatory positions in Ukraine through donations, humanitarian aid, and publicizing their demands.

- Support progressive anti-war and anti-regime forces in Russia and publicize their positions.

- House Ukrainian exiles and organize events and infrastructure to make their voices heard.

- Combat all pro-Putin discourse, especially on the left. The war in Ukraine offers a crucial opportunity to put a definitive end to campism and toxic masculinity.

- Combat pro-NATO discourse by ideology.

- Refuse support to those in Ukraine and elsewhere who defend ultra-nationalist, xenophobic, and racist policies.

- Permanent criticism and distrust of NATO’s actions in Ukraine and elsewhere.

- Maintain pressure on governments via demonstrations, direct action, banners, forums, petitions, and other means in order to enforce the demands of self-organized actors on the ground.

Unfortunately, this is not much, but it’s all we can offer as long as there is no autonomous force here or elsewhere fighting for equality and emancipation that is capable of providing economic, political, or military support.

We sincerely hope that, this time, these positions will carry the day. If that happens, we will be deeply happy, but we will never forget that this was far from being the case for Syria, and that it cost it dearly.

—The Syrian Canteen of Montreuil and L’équipe des Peuples Veulent

Sources and Further Reading

The following texts informed this article or offer useful points of departure from it.

Voices of Resistance in Ukraine and Russia

- The Kyiv Declaration: Ukrainian Civil Society Leaders Appeal to the World

- Manifesto: Russian Socialists and Communists against the War—BALLAST

- A Letter to the Western Left from Kyiv—OpenDemocracy

- Ukraine and Russia: Grassroots Resistance to Putin’s Invasion—CrimethInc.

- Russian Anarchists on the Invasion of Ukraine: Updates and Analysis—CrimethInc.

- Against Annexations and Imperial Aggression: A statement from Russian Anarchists against Russian Aggression in Ukraine—CrimethInc.

- War and Anarchists: Anti-Authoritarian Perspectives in Ukraine—CrimethInc.

- Spring is Coming: Take to the Streets against the War—Call for Demonstrations in Russia against the Invasion of Ukraine—CrimethInc.

To Pursue the Questions of Imperialism and Internationalism further

- Against Russian Imperialism, for an Internationalist Leap, Mediapart

- Their Anti-Imperialism and Ours—Gilbert Achcar

- A Memorandum on the Radical Anti-Imperialist Position Regarding the War in Ukraine—Gilbert Achcar

- There Will Be No Scenery after the Battle—The Zapatista Sixth Commission

Syrian Perspectives

- The “Anti-Imperialism” of Idiots—Leila Al Shami

- Safe—On the Edge of Syria

- Why Ukraine Is a Syrian Cause—Yassin al-Haj Saleh

- أوكرانيا بعيون سوريّة

-

This Twittter thread by Joey Ayoub compiles a great deal of material connecting the Syrian and Ukrainian contexts.

https://twitter.com/Ahmad_Baqari/status/1497480750547062786

https://twitter.com/SyriaCivilDef/status/1499160006264033282

On the Role of NATO and Westerners

Appendix: Regarding the Flag of the Syrian Revolution

While it is true that the flag associated with the Syrian Revolution is also carried by militias who betrayed the revolution by allying with the Turkish government during its occupation of northern Syria and other territories, for the authors of this text, this symbol—seen in the photographs from Kafranbel—still represents the uprising of 2011. It was the flag of Syria when it declared its independence from France. By contrast, the current “official” flag (with two stars) symbolizes the domination of the Ba’ath party and a new colonization of Syria by the al-Assad family.