In response to Emmanuel Macron’s proposal to increase the tax on fuel for “ecological” reasons, France has experienced several weeks of unrest associated with the yellow vest movement. This grassroots uprising illustrates how the contradictions of modern centrism—such as the false dichotomy between addressing climate change and considering the needs of the poor—can create social movements that offer fertile ground for populists and nationalists. At the same time, the increasing involvement of anarchists and other autonomous rebels in the unrest raises important questions. If far-right groups can hijack movements, as they did in Ukraine and Brazil, can anti-capitalists and anti-authoritarians reorient them towards more systemic solutions?

“The yellow vests will triumph”—but what will triumph with them?

On Tuesday, December 4, the Macron government offered its first concession, delaying the fuel tax for six months. But the story has yet to reach its climax. Protests and police violence around France continue unabated; now truck drivers and high school students are involved. The yellow vest model has already spread to Belgium and there are demonstrations called in Spain and Germany.

Another day of action has been called for this Saturday; for the first time since the beginning of the movement, trade unions have officially announced that they will take part. Rail workers, students, and anti-racists are calling for people to gather at 10 am near Saint Lazare train station. In other words, it seems that another anti-fascist and anti-capitalist bloc is planned for Saturday. The government is preparing to intensify state violence once more in response to this. All the members of the government say that they are “really scared for Saturday.”

As seems usual these days, no one on any side of the conflict seems to have any strategy in mind except to continue escalating.

But who will benefit from this escalation? Will it radicalize ordinary people, equipping them to defend their livelihoods against neoliberal austerity measures by means of direct action? Will it offer the police state a new justification for further repressive laws and measures? Will it bring a far-right nationalist government into power in place of the government of Macron?

Likewise, if this internally contradictory movement spreads to other parts of Europe, what aspects of it will spread? Will it supplant xenophobic populism with popular rage about the economy, clearing the way for a new wave of anti-capitalism? Will it offer a vehicle for the far right to create a surge of grassroots nationalism, opening a new era of fascist street violence? Will it continue to be a battleground on which nationalists, anarchists, and others vie to determine what form the opposition to centrists like Macron will take in the years to come?

Let’s get some perspective on the situation.

In the United States, in less reactionary times, the Occupy movement saw some of the same conflicts emerge. Legalistic liberals, leftist pacifists, insurrectionist anarchists, far-right crypto-fascists, and unaffiliated angry poor people all converged in the movement and fought to determine its character. At first, it was unclear whether Occupy would be most useful to middle-class democrats, right-wing conspiracy theorists, or the genuinely poor and desperate; in fact, in September 2011, we heard some of the same pessimism about Occupy that we heard from anarchists about the yellow vest movement in November 2018. However, after a few weeks, anarchists and other militant opponents of capitalism and white supremacy seized the initiative, especially in Occupy Oakland, focusing the movement on confronting the root causes of poverty and ensuring that many of the people who were radicalized during Occupy adopted emancipatory rather than reactionary politics.

We saw the opposite process play out in Ukraine two years later, when fascists gained the initiative via the very same approach anarchists had used in Occupy Oakland—taking the front lines in clashes with the police and forcing their political adversaries out of organizing spaces.

Today, the far right has made considerable gains since 2014, and conflicts worldwide are playing out at a much fiercer pitch than they were in the days of Occupy. France has a long history of movements for liberation, including many powerful struggles over the past decade and a half. Hopefully, these have created powerful networks that will not let nationalists take the lead in determining what social movements in France will look like.

But even if we understand the movement itself as a battleground, that only poses further questions. What is the best way to influence the character of a movement? How do we engage in this struggle in a way that doesn’t weaken the movement, offering the advantage to the police? How do we remain focused on connecting with other ordinary participants in the movement rather than getting mired in a private grudge match with fascists?

The fog of war.

In order to explore these questions in greater detail, we present the following update from France. This report picks up where our previous analysis left off, in the aftermath of the yellow vest demonstration of November 24.

The Aftermath of November 24

A week ago, total confusion reigned about the yellow vest movement—and within it. The self-proclaimed “leaderless,” “spontaneous,” and “apolitical” movement against the increase of taxes on gas had reached its first impasse. How could the movement remain unified when people from across the entire political spectrum were participating with completely contradictory views about how to address the government, what sort of tactics to employ, and what narratives to rally around? At the same time, how could the movement resist the attempts from political opportunists and party leaders to coopt it, while continuing to push? The yellow vest movement was fracturing over these issues.

The yellow vest movement is a battleground for the entire political spectrum.

The day after the Parisian demonstration on Saturday, November 24 that saw the avenue of the Champs Elysées transformed into a battlefield between demonstrators and police, part of the movement voted to elect eight official spokespersons. In doing so, they hoped to reintroduce some good old-fashioned hierarchy and centralization into the movement, so as to establish dialogue with the government.

Once again, with these elections, it was not easy to maintain the appearance that the yellow vest movement was “apolitical.” Two of the newly elected spokespersons had connections with the far-right:

-

Thomas Mirallès ran for the Front National (now Rassemblement National) in the 2014 municipal elections. To defend himself, he describes this political experience as “a youthful mistake” and emphasizes that since that election, he “has never campaigned again.”

-

On social media, Eric Drouet has shared videos against migrants and expressed arguments used by the xenophobic far right. Knowing that this could tarnish his new “respectable” image as a spokesperson of the movement, he deleted all his Facebook publications up to November 18.

However, these elections were rejected by another part of the movement that refused to fall into the traps of representation and negotiation. Some yellow vesters explicitly reject the concept of representation: rather than having a spokesperson, the idea is that every participant should speak for himself or herself. Moreover, after the intense confrontations that took place during the November 24 demonstration in Paris, several local organizers decided to distance themselves from the movement.

The conflict within the movement didn’t stop some determined yellow vesters from calling for another day of action on Saturday, December 1, in order to increase the pressure on the government to rescind the tax—or simply to destabilize the government itself. The tone was set!

State power, destabilized.

The Government Tries Dialogue

It is clear now that the French government was not expecting the demonstrators’ rage to escalate, producing hours of rioting in Paris. When another call appeared to demonstrate in Paris the following weekend, the government realized that they were losing control of the situation. This is why, after weeks of expressing contempt towards the yellow vest movement, members of the government changed their strategy in hopes of pacifying the situation. In this regard, the decision to elect official spokespersons for the movement was a strategic mistake, in that it facilitated the government’s efforts to establish a “dialogue” in which politicians would dictate terms to representatives who would then dictate them to participants.

On Tuesday, November 27, President Macron made a public speech in order to present the creation of the Haut Conseil pour le Climat (the High Council for Climate), the purpose of which is to “provide an independent perspective on the Government’s climate policy.” During his speech, President Macron changed his strategy by directly addressing some of the demands and concerns of the yellow vesters, presenting himself as a pedagogue willing to listen to what people have to say. This political masquerade failed; many members of the yellow vest movement rejected the so-called “helping hand” offered by the president and criticized his hypocrisy, as Macron had categorically refused to meet some yellow vesters just that morning.

Later that day, at the request of President Macron, the Minister of Ecological Transition, François de Rugy, received the leading figures of the movement. This meeting was supposed to establish some kind of dialogue between the government and the movement in order to find an exit from the situation. However, after two hours, the deadlock remained. Unconvinced by their exchange with the minister, the two spokespersons reaffirmed their intention to demonstrate on Saturday, December 1.

Understanding that the situation was escalating as more and more yellow vesters rejected the idea of dialogue and committed to gathering in the streets, the government tried one more time to re-establish dialogue. On November 30, Prime Minister Edouard Philippe invited the eight spokespersons of the movement to a meeting. This meeting was a failure, too: in the end, only one spokesperson out of eight met with the Prime Minister and the Minister of Ecological Transition. A second spokesperson, Jason Herbert, left the meeting shortly after it began.

Yellow for all.

A Fertile Ground for Populists

That same week, the self-proclaimed “legalist” and “official” part of the movement, including the elected leaders and spokespersons for the yellow vests, presented traditional media outlets with 42 demands. Looking at this list, it is easy to see the confusion within the movement, but also to identify some of the political influences that its protagonists share.

The list includes demands from every position on the political spectrum. There are social demands such as increasing minimum wage, fighting homelessness, and increasing financial assistance to handicapped people. But there are also reactionary demands, including deporting immigrants who haven’t received the right to asylum, blocking migration, developing a policy of assimilation for those who want to live in France, increasing the presidential term from 5 to 7 years, and providing more funding to the Justice department, the police forces, and the army.

Alongside these demands, we saw the now “classic” opposition to the increase of taxes on gas, as well as some ecological, protectionist, and nationalist arguments. The “legalist” or “official” part of the movement was playing a dangerous game in giving populists from the left to the far right reason to support the movement, if not enabling them to coopt it completely.

Jean-Luc Mélenchon, leader of the leftist populist party France Insoumise, publicly denies that his party has engaged in any efforts to coopt the movement; in reality, the populist leader, who is obsessed with the idea of a coming “citizens’ revolution,” is hoping that the anger in the streets will weaken Macron’s government. This is purely opportunistic, as the leftist populist party aims to increase its ranks by attracting “angry” voters in the 2019 European elections.

On the other side of the political spectrum, emboldened by the wave of far-right victories in the US, Italy, and Brazil, nationalists know that this movement of collective anger represents a great opportunity for them to gain power and confirm their status as a “real political alternative” to the current government. Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, leader of Debout La France, has been supporting the movement from the beginning, and some yellow vesters are members of his political party—Frank Buhler, for example, whose video became viral online.

Marine Le Pen, leader of the Rassemblement National, believes that the yellow vest movement represents what she’s been describing for years as “the France of the people left behind.” The nationalist party believes that “Yellow vesters look like our voters. Unhappy and unlucky people because they are usually invisible, and who have a strong contempt for politicians.” This explains why the Rassemblement National has been extremely cautious in terms of strategy. They fear that if they attempt to coopt the movement too obviously, they could turn the demonstrators against them. They decided instead to offer verbal support to the demonstrations without their leaders marching in the streets alongside protestors. They have concentrated on communicating and defending some of the “42 demands” in corporate media outlets. Marion Maréchal Le Pen, niece of Marine Le Pen, said that she was present at the Champs Elysées on November 24 and described herself as “an ardent moral support for the yellow vesters’ suffering,” claiming to have “a lot of empathy for them.”

December 1 in Paris.

Preparing for the Unknown

Frustrated at having failed to neutralize the movement through dialogue, and fearing that, for the second week in a row, images of chaos in the streets of Paris would dominate the airwaves, the government decided to take every possible measure to maintain its precious republican order during the demonstrations of Saturday, December 1.

To secure the capital city, prevent or contain confrontations, and deal with the infiltration of radicals and “extremist elements,” the government arranged 5000 anti-riot police (Gendarmes and CRS) for the day. Their mission was to control all the access routes to the Champs Elysées, the meeting location of the demonstration. To ensure that no dangerous objects or possible projectiles would be brought inside the demonstration, the authorities filtered the access points, searching every single person who wanted to enter the perimeter. These controls were to be in effect from 6 am on Saturday, December 1 until 2 am on Sunday, December 2.

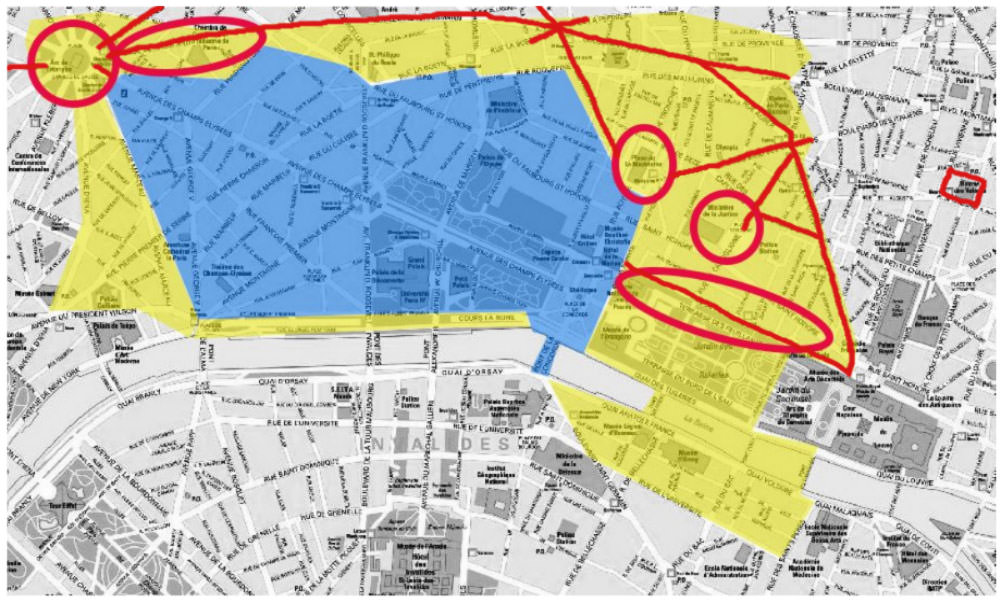

In order to protect the most important buildings, symbols, and organs of power, the authorities designated restricted areas where freedom of movement would be limited. All access to the Elysée (the Presidential palace), the Place Beauvau (the Ministry of the Interior), the Hôtel Matignon (the Prime Minister’s office), or the National Assembly was sealed off completely for the day.

Another reason the government took all those safety measures was that the yellow vests were not the only group demonstrating that day in Paris. At 10 am, railway workers were supposed to gather near the Saint Lazare train station to defend their status; they planned to join the yellow vesters after their action. At 12 pm, other trade unions were gathering for a traditional annual march against unemployment and precariousness. At 1 pm, several collectives of Parisian suburbs and anti-fascists decided to gather at Saint Lazare to join the yellow vest movement.

In short, on the eve of the December 1 national day of action, all the elements were combining to make for a truly explosive mixture in the streets of Paris.

All cops are bastards; all cars are barricades.

The Fuse Is Lit…

Due to the dramatic scope of what happened on December 1, we cannot provide an exhaustive list of all the actions and confrontations that took place in the streets of Paris that day. This is only an incomplete overview of the course of events. Also, in reference to the images and stories presented herein, it bears saying that some of the protagonists may be members of the far right.

Early in the morning, the first demonstrators began to converge on the Champs Elysées. Police were already deployed and on the alert; all yellow vesters were searched before entering the perimeter of the demonstration. The trap set up by the government was in effect. During the first few hours of the day, police arrested several individuals on accusations of possessing weapons and projectiles.

This map depicts the zones that were declared forbidden or restricted.

This map depicts the part of Paris where the clashes took place. In blue, the restricted area controlled by police forces; in yellow, the areas where yellow vesters circulated; in red, the major confrontation zones, including the route taken by some anarchist comrades in their report.

Surprisingly, the safety plan set up by authorities protected the avenue of the Champs Elysées, but not the Place de l’Etoile—the large traffic circle around the Arc de Triomphe. Proposed by Napoléon I in 1806, the Arc de Triomphe was inaugurated in 1836 by Louis Philippe, then King of France, who dedicated the monument to the armies of the Revolution and the Empire. In 1921, the French government buried the Unknown Soldier of World War I beneath it. The flame of remembrance is revived everyday and official military commemorations take place annually in front of the flame. The monument is a symbol of French glory.

Aware that the Arc de Triomphe was not under police control, and knowing that, to access the Champs Elysées, they would have to submit to a search and have their identities checked, demonstrators began to gather around the monument, just outside the police perimeter. At 8 am, about a hundred yellow vesters were already on site, while the official beginning of the demonstration was due at 2 pm. Shortly after, around 9 am, the first confrontations began when yellow vesters tried to force their way through a checkpoint to enter the Champs Elysées. Police responded immediately with tear gas, which only escalated the clashes.

From this vantage point, it is not easy to confirm precisely who initiated the first confrontations or who took part. As during the previous week, the confrontations included everyone from neo-Nazis and other fascists to anarchists, anti-capitalists, and anti-fascists, not to forget angry yellow vesters from many other different backgrounds and political tendencies.

As is becoming usual with the yellow vest movement, the situation was quite confusing. Some protestors gathered around the Unknown Soldier’s flame as if they were paying tribute to war, nationalism, and imperialism. Others started singing the Marseillaise—the French national anthem. Meanwhile, the more determined protestors were throwing cobblestones at police forces, erecting barricades in the neighboring streets, and setting cars on fire.

Soon, the entire traffic circle was enveloped in tear gas. The situation continued to escalate. Every time the police line got too close, rioters welcomed them with a shower of cobblestones and other projectiles. In the meantime, the first tags appeared on the Arc de Triomphe; this imperial symbol was finally profaned! Sadly, although some of the tags were clearly inscribed by anarchist and anti-statist comrades, others were written by fascists.

The Arc de Triomphe.

French taxes at work.

The presence of organized fascist groups during the clashes around the Place de l’Etoile during the morning of December 1 is undeniable. Several mainstream media outlets covering the yellow vest movement mentioned their presence among the yellow vest movement. In one article, the journalist says: “Several police vehicles had to leave the Place des Ternes hastily after being attacked by tens of individuals wearing visible far-right symbols.” In another article, the author reports the presence of monarchists, traditionalist Catholic groups, and nationalist and fascist groups, such as the GUD (Groupe Union Défense), a far-right student union—backing up these claims with photographs.

In their personal report about the yellow vest demonstration, anarchist comrades also mention the presence of the far right near the Place de l’Etoile:

“When we arrived at the Place de l’Etoile around 12 pm, it had already been a huge chaos for almost three hours. According to some comrades we met on site, the confrontations had been extremely violent underneath the Arc de Triomphe during the morning. It seemed that a lot of people had been injured. It was also in this area that radical far-right groups were most present during the day. The GUD was there. We saw a good amount of walls covered by Celtic crosses. The far right in its “legalist” tendency also appeared to be well-represented among the demonstrators. It seemed to us, and according to several other testimonies as well, that these fascist tendencies stayed present all day long around the Place de l’Etoile. Nevertheless, it was difficult to really quantify them.”

The Arc de Triomphe was the focal point of confrontations throughout the morning. Police repeatedly tried to repel protestors from the historical monument, but not without difficulties, as evidenced by this scene in which a group of demonstrators charged an anti-riot police unit that was trying to protect the edifice. During the charge, one policeman was isolated from his unit and beaten up by yellow vesters.

Clashes at the Arc de Triomphe.

This event illustrated once more the confusion and disagreement within the movement. While some yellow vesters were attacking the police officer, others helped him to escape from his attackers, so he could rejoin his unit. Later, another yellow vester even returned an anti-riot shield to the police after demonstrators had seized it.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the French capital, other people in yellow vests gathered in the district of Bastille and walked along the large street of Rivoli, passing in front of the main City Hall of Paris, with the objective of entering the Champs Elysées from the opposite side—via the Place de la Concorde.

The museum under the Arc de Triomphe.

…Now It’s Time to Explode

The following section draws on this narrative published by anarchists, complemented by information from corporate media and other sources.

Around 1 pm, while the Arc de Triomphe was still surrounded by massive clouds of tear gas, a group of comrades decided to change their strategy and create a new dynamic by starting a wildcat demonstration and leaving the stalemate around the traffic circle behind them. Rapidly, a procession of 800 individuals left the square and entered the streets of wealthy Parisian districts. The crowd was quite heterogeneous, but the atmosphere seemed friendly.

On the Hoche avenue, the wildcat demonstration ran into a large procession of railway workers who were heading towards the Saint Lazare train station in order to join the afternoon call made by suburban and anti-fascist collectives. Without thinking twice, the two processions united and continued to march towards the meeting point. This development shifted the horizon of possibility for the rest of the day.

When all the processions converged in the luxurious Opéra district, thousands of individuals were marching through the streets. Over a century ago, during the Belle Epoque era, anarchists such as Emile Henry demonstrated the concept of propaganda of the deed in this neighborhood by attacking the rich and their symbols in their own luxurious district. Here, in contrast to the ambience around the Arc de Triomphe, the atmosphere was comfortable. Within this large procession, there were anarchists, anti-fascists, queer radicals, collectives against police violence, railway workers, garden variety yellow vesters, some people we might describe as rioters without adjectives, and many others, including the simply curious. For the first time, it really seemed that some kind of anti-capitalist and anti-fascist force could gain a foothold within the troubled waters of the yellow vest movement.

Heading south, the large procession finally arrived at Rue de Rivoli—a large street that connects Bastille to the Place de la Concorde, the highly restricted area near the Presidential palace. At this point, part of the crowd decided to go east and continue marching towards the City Hall of Paris—where they were welcomed by police forces with tear gas. The rest of the procession, about 1500 individuals, were determined to go the opposite way and force their way through the police checkpoint near Place de la Concorde.

When they approached the square, numerous police trucks and a water cannon blocked their way. Uninterrupted and intense confrontations followed between radicals and police forces. Barricades appeared on different fronts, projectiles were thrown at police, while a rain of tear gas canisters fell on protestors and the water canon attacked them at full blast. Eventually, however, the water canon seemed to have some technical issues. Some demonstrators seized this opportunity to set a car on fire for use as an additional barricade.

A barricade.

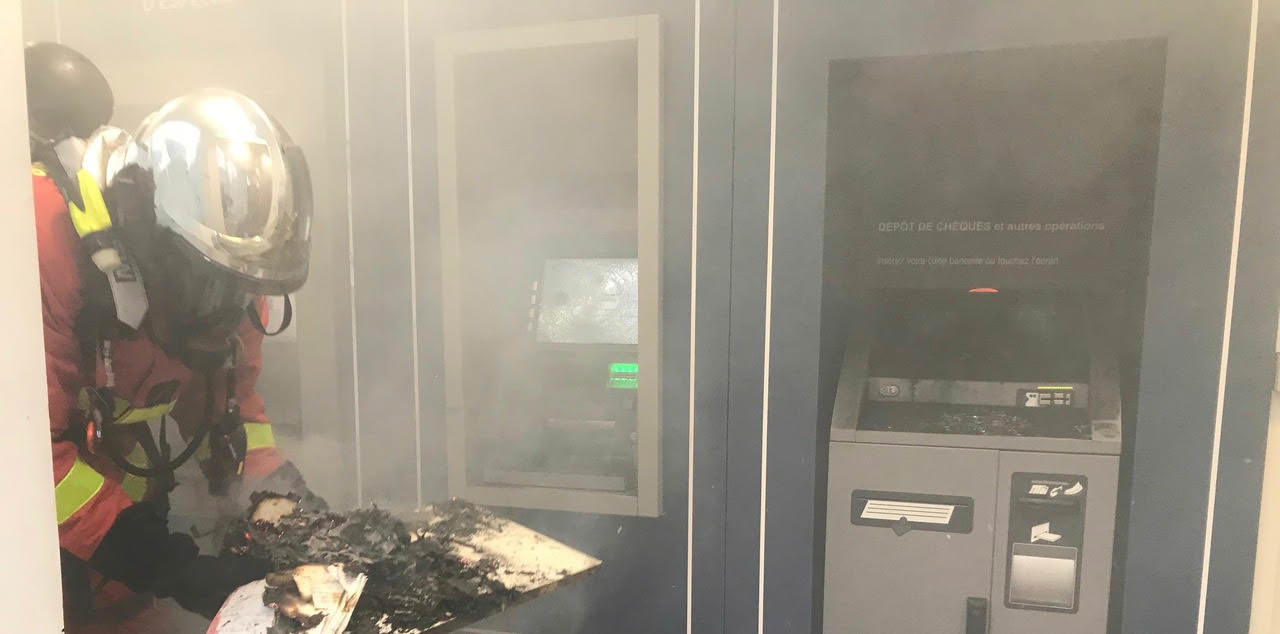

Further away, near Saint Augustin, about 3000 individuals had been gathering at a major intersection since 3 pm, building numerous barricades in the area to block traffic. People were joyously expressing their desire to overthrow President Macron. The fences of a nearby construction site were used to erect new barricades, while others were set on fire. A little further away, police forces were already blocking the streets. At this point, mounted police also appeared. Not thinking twice, protestors began breaking up the asphalt and throwing projectiles at the police. For over an hour, a confrontation continued at this intersection. This shows how determined people were that afternoon. In the meantime, a nearby bank was thoroughly damaged, while other demonstrators flipped a truck over. Law enforcement finally cleared the area of protestors with a massive tear gas attack.

Christmas comes early to Paris.

Several different parts of Paris were completely chaotic. Three cars were burning on the fancy Haussmann Boulevard, named for the reactionary urban planner who attempted to make Paris insurrection-proof after the revolution of 1848. Several streets further, an empty police car was destroyed, looted, and set aflame. A crowd of radicals arrived at Place Vendome, well known for its luxurious jewelry stores, the Ministry of Justice, and the infamous column that the Communards once destroyed. Plastic Christmas trees found in the nearby streets were piled up as barricades and set on fire.

While a thick cloud of smoke enveloped the Opera district, the anti-capitalists decided to move towards the Bourse, the historical stock market building—another symbol of capitalism and state power. Granted, since 1998, no more financial transactions are made inside this building. Nevertheless, several windows were smashed, the front doors were opened, and fireworks made their way inside the hall. Then the rioting crowd left the area, attacking another police car in a neighboring street on the way. They used urban furniture and construction equipment to block traffic, destroyed the front windows of several banks, and disappeared into the early night.

One day, all that money will just be burning garbage.

The evening of December 1.

The emergence of some kind of anti-capitalist and anti-fascist bloc was an important development within the yellow vest movement. Likely drawing on years of experience in demonstrations such as the May Day and Loi Travail protests, the bloc took advantage of the general confusion to carry out multiple actions throughout Paris with clear objectives and intentions.

In addition to the clashes with police, there were also several confrontations with fascists. Members of the GUD were seen on a barricade with a Celtic cross flag. In another instance, protesters recognized Yvan Bennedetti—a well-known Nazi and former president of the ultranationalist Oeuvre Française, which disbanded after the killing of anti-fascist Clément Méric in 2013. He was effectively forced out of the area, if not out of the movement as a whole.

On Saturday, December 1, an insurrectional wind blew through the streets of Paris. Many thousands of people unleashed their rage against symbols of power: police were constantly harassed; banks and insurance agencies were systematically destroyed; numerous stores were looted, some even set on fire; cars and urban furniture were used to build barricades; several private mansions were vandalized and set on fire; historic monuments and republican symbols were occupied or attacked, including the Bourse and the Arc de Triomphe. Demonstrators succeeded in entering, looting, and destroying the museum located beneath the historical monument.

Scenes from December 1.

In view of such determination, the government and police forces were completely overwhelmed. There are several explanations for this. The first reason is the wide range of people taking part in the riots. It was not just anarchists and anti-capitalist radicals attacking police forces, but also a great number of other angry people in yellow vests including far-right activists and other rioters. Secondly, the protests continued to change and develop throughout the day, assuming unpredictable new forms. Finally, the extreme mobility, diffuse organization, and determination of the protestors made them a match for the officers, who were pinned down by their task of defending predefined areas. Indeed, as most police forces were assigned to positions around the restricted areas or busy dealing with confrontations near the Champs Elysées, they couldn’t respond to the developments in other districts of Paris. Nevertheless, on several occasions, members of the BAC (Anti-Criminality Brigade) were seen in the streets haphazardly shooting rubber bullets at every demonstrator in view.

Many officials and media agree that Paris hasn’t experienced such riots since 1968. To this assessment, we must add the following figures.

-

Altogether, 412 individuals were arrested and 378 of them were put in custody.

-

It is difficult to tell how much ammunition the police used; numbers vary widely between sources. However, it appears that they deployed about 8000 tear gas grenades, 1000 sting-ball grenades, 339 GLI-F4 stun grenades, 1200 rubber bullets, and 140,000 liters of water during the confrontations.

-

In the end, during the Parisian demonstration alone, 133 individuals were injured, while the authorities counted 112 cars, 130 pieces of urban furniture of one kind of another, and six buildings set on fire for a total of 249 fires.

-

The total amount of property destruction could reach 4 million euros.

The clashes around the Arc de Triomphe continued well into the night.

The police unloading even more ammunition.

Some of the consequences.

If you want us to spend more on gas, you may spend more on cars.

Fire Spreads on the Wind

Paris was not the only place in France where yellow vesters expressed their anger with actions. In various cities, protestors gathered for this third nationwide day of action; some of them were as determined as those who took the streets in Paris.

In Nantes, the first actions took place at the airport, where demonstrators succeeded in entering the tarmac. In the afternoon, about a thousand yellow vesters gathered in the streets of Nantes. The demonstration didn’t last very long; as soon as protestors tried to enter to the shopping district, police deployed massive quantities of tear gas to disperse the march.

In Toulouse, intense confrontations took place between yellow vesters and law enforcement. In Narbonne, yellow vesters set fire to a toll collection point. In Bordeaux, clashes erupted between police and protesters when the crowd of yellow vesters arrived at City Hall and tried to enter by force.

In Tours, a demonstration drew about 1300 individuals. Shortly after the beginning of the march, participants began smashing shop windows, and confrontations with police escalated. One yellow vester lost his hand as a consequence of a grenade thrown by police.

In Marseille, the confrontations began at the end of the day. Protestors burned trash containers, smashed several shop windows, looted stores, set a fire in front of the city halls of the 1st and 7th districts, and finally set a police car on fire in front of the Canebière police station. It appears that 21 individuals were arrested after these actions. An 80 year old women was killed when a tear gas grenade hit her in her face as she was closing her shutters.

Finally, about 3000 individuals gathered at Puy-en-Velay. Yellow vesters entered the courtyard of the local Prefecture with tires and refused to leave. Some of them set fire to the tires. Police forces tried to disperse the crowd by using tear gas, but this only increased the anger of the demonstrators. Numerous confrontations followed. The prefect himself tried to discuss with the protestors in order to bring back order but without any success. In the end, dissatisfied with the situation, yellow vesters burned down the Prefecture.

A day of chaos.

The Aftermath

The day after the demonstrations, the government knew that it had reached an impasse of its own. President Macron was on a trip to Buenos Aires for the G20; as soon as he heard about the situation in Paris, he returned to France immediately to deal with this major political crisis.

On Sunday, December 2, President Macron met with some of the policemen and firemen who had been in the streets the previous day. He also made a small tour of the damages caused by hours of insurrectional confrontations before heading back to the Elysée palace for an emergency meeting with all of the government. The President asked his ministers to cancel all their business trips for the next two days.

President Macron did not make any official declaration after the meeting. Nevertheless, he personally asked the Prime Minister Edouard Philippe to see all the political leaders of the different parties the next day, as well as the spokespersons of the yellow vest movement.

In the meantime, the left populist Jean-Luc Mélenchon requested that every political group in the National Assembly opposed to the government should make a vote of no confidence to denounce the “catastrophic management of the yellow vest issue.” At the same time, the far-right leader Marine Le Pen demanded the dissolution of the National Assembly. Once more, it is not difficult to see who wants to take advantage of the situation.

On Saturday night, the Minister of the Interior said that he was willing to consider all possibilities to ensure republican peace and order in France, even re-imposing the state of emergency to deal with the yellow vest movement. This is gratuitous: in the new antiterrorist law adopted on October 31, 2017, many of the elements that constituted the exceptional aspect of the state of emergency are now fully integrated into ordinary French common law—for example, the creation of restricted zones during events.

Nevertheless, on Sunday, December 2, yellow vesters determined to push their movement further were already planning a fourth round with the government, calling for another national day of action on Saturday, December 8. It happens that on the same day, the global climate march will take place in Paris. For the occasion, radicals have made a call for an offensive contingent. We will see whether it is possible for these two movements to establish a connection.

On Tuesday, December 4, Prime Minister Edouard Philippe said that the government had decided to suspend gas tax increases for the following six months. In addition, the government is also suspending new tougher rules on vehicle checks for the same amount of time, and committing not to increase electricity fares until May 2019. In addition, the Prime Minister announced that a debate about taxes and public expenses at a national scale would take place between December 15, 2018 and March 1, 2019. In making these concessions, the government aims to show that it is open to dialogue with yellow vesters.

Nevertheless, it seems that part of the yellow vesters are not willing to give up the fight. The spokespersons of the yellow vest movement rejected the invitation from the Prime Minister to find a way out of the current situation; several local yellow vests groups are calling to continue their actions.

So far, the government’s announcement does not seem to have had much effect upon the ranks of the yellow vest movement. Since the beginning of the movement on November 17, the number of demonstrators has dropped as the intensity of conflict has escalated. Yet even if some yellow vesters have dropped out due to the increasingly confrontational strategy, the last day of action showed that some demonstrators are determined to continue forward.

We still have an unknown horizon before us—and so many dawns yet to break.

Revolutionary optimism.

Some Reflections

As we hoped, an anti-capitalist and anti-fascist front has emerged within the yellow vest movement. In Paris on December 1, this created a convergence point and catalyst for people who do not identify with nationalist narratives. Hopefully, this will help to spread a discourse that identifies the structural causes of Macron’s programs, rather than framing them as the “betrayals” of a politician who should simply be replaced with a more nationalistic populist.

In only three weeks, the yellow vest movement has gone from blocking traffic to demolishing the wealthy districts of Paris. This illustrates the efficacy of direct action, horizontality, and the refusal to negotiate. In the era of globalized capitalism, any movement that is to face down the neoliberal assault on the living standards of ordinary people will be forced to escalate in this manner and to resist all attempts to control, represent, or placate it.

As many anarchists have emphasized before, effective resistance to capitalism requires the participation of a wide range of people, not just those who share a common ideological framework. This means that a movement must spread beyond the control of any one group or position. Indeed, we can understand the yellow vest movement as a widespread popular appropriation of the confrontational tactics that anarchists and other rebels have been employing in France for years—for example, in the protests against the Loi Travail and on May Day.

Yet the widespread appropriation of radical tactics is not necessarily a step towards a better world unless people also absorb the values and visions that accompany them. The rise of Trump and grassroots nationalism in the US has been marked at every step by the far-right appropriation of left and anarchist rhetoric and tactics, which they have used to advance their own agenda.

What happens inside a movement against the reigning government is just as important as what happens in the conflicts between that movement and the police. This is why we have emphasized the importance of fighting on two fronts—against Macron’s police and likewise against fascists and nationalists.

United colors of resistance?

There’s No Such Thing as an Apolitical Movement

From the outset, the yellow vest movement has claimed to be an “apolitical” space open to all. This has offered fertile ground for populists and nationalists to promote their ideas. In most cases, they have not been the majority of those taking action in the streets, but they have often set the discourse online. Fascist groups have gained visibility, too, even if their number seems comparatively modest. They are better organized now than they were at the beginning of the movement. We must not abandon the streets and the movement to the far right.

No social movement is a monolith; each is a heterogeneous space of perpetual change and tension. It is foolish to deem movements worthy or unworthy, standing in judgment like the Pope, relinquishing the ones that do not meet our standards to the influence of our adversaries. Instead, we can aim to participate in ways that enable the emancipatory currents within them to gain momentum and become distinct from the reactionary currents. The challenge is to offer our fellow participants useful examples of how to solve their immediate problems and to connect those with visions of long-term change—and to do all this without creating tools or momentum that fascists, authoritarian leftists, or other opportunists can capitalize on.

Perhaps we should think more about the relationship between street battles and the battle of ideas. Historically, anarchists have often assumed that those who are willing to take the most risks will be best positioned to determine the character and goals of a movement. On the ground, this is often true—for example, when a movement escalates conflict with the police, it can force centrists and legalists to withdraw. But we should also remember all the times that rebels from oppressed groups have taken the most risks and suffered the most repression, only to see authoritarians take advantage of their sacrifices to consolidate their power. This is a very old story, from the French revolutions of 1830, 1848, and 1870 and the Italian Risorgimento to the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the Egyptian Revolution of 2011.

We should bear all these lessons in mind when we weigh whether the best way to gain leverage within a movement is to be the ones who take the most risks within it. How can we make sure that our adversaries within the movement cannot force us to take the majority of the casualties while they simply—take power?

Likewise, if our only idea for how to gain leverage within a movement is to engage in the most dangerous or disruptive activity, far-right groups with greater social privilege and more access to resources may be able to beat us on that playing field while taking fewer losses.

A decade ago, in less complicated times, some anarchists and autonomists imagined that, rather than being connected by a common set of values and aspirations, people in revolt could be connected simply by behaving ungovernably in relation to the prevailing authorities. It is still possible to find examples of this “anti-ideological” attitude in France today, despite the evidence that at least a few of those who wear the yellow vest are simply fighting to enthrone other authorities who will be just as dangerous when they come to power. It would not be the first time that rebellious street violence brought a new oppressive government into office.

Yes, the order that reigns must be undermined by any means necessary. The same goes for the proponents of rival ruling orders. Driving Yvan Bennedetti out of a demonstration is just as important as defending it against the police.

At the same time, it must be clear to all the newly mobilized and politicized participants in these movements that we are not simply robots acting according to a pre-programmed ideological framework, but that we genuinely hope to connect with them, exchange ideas and influences with them, and work together to create solutions to our mutual problems. We are not trying to seduce them into joining our party, but seeking to become something new together. Our opposition to authoritarians is not a tenet of a religion, but a hard-won lesson about what it takes to create spaces of freedom and possibility.

In this regard, the moments of dialogue between strangers that take place in the street are just as important as the courageous acts by which people hold police at bay and force out fascists. Let’s not be naïve, let’s not disavow our opinions or abandon our convictions, but let’s remain open to the possibility that we could become stronger and more vibrantly alive by working with others we have not yet met, who share our problems but not our reference points.

The Long Game

Sooner or later, this moment of crisis will pass—either the leaders will cut a deal with the state and the police will succeed in isolating those who refuse to cooperate, or Macron’s government will fall and be replaced by another that promises to solve the problems that drove people into the street.

And what then? Will the far right be able to claim that they were the ones who scored the victory against Macron? Most of the aforementioned 42 demands are compatible with both leftist and far-right populist programs; it would not be surprising to see the movement split in two and be coopted by the two populist parties. Since the riots last weekend, both populist leaders have been galvanized by the demand to oust President Macron and his government. It is entirely possible that a far-right government will come to power after Macron.

What should we be doing right now to prepare for that situation, to make sure that people will continue to come together in the streets against the next government?

As we fight—in France, in Belgium, and everywhere else that neoliberal governments are forcing austerity measures on us—let’s be thinking about how to come out of each fight more connected, more experienced, and with a sharper way of identifying the questions before us.

Good luck to each of you, dear friends.

Further Reading: Comparing the Yellow Vests with Ukraine and Italy

Gilets Jaunes et Extrême Droite: Les Leçons de Maïdan

Les Gilets Jaunes à la lumière de l’expérience italienne

Uncertain futures.