Since October, the territory nominally controlled by the Chilean government has seen massive demonstrations against capitalism and the state that have opened up exciting new possibilities for social transformation. The movement has shown unprecedented longevity and resilience in the face of brutal repression and efforts at co-optation. With the summer vacations coming to a close, a new chapter of this story is about to begin. Our comrades in Chile present an overview of the situation along with translations of recent texts from anarchists on the ground in the movement—focusing on anarcha-feminism, the rejection of electoral politics, and strategies for toppling state power.

Rich or poor, urban or rural, for or against a new constitution, everyone in Chile has been repeating the same phrase for a month now: “March is coming.” You see it on the news. You hear it in the streets. It’s the punctuation mark at the end of every casual conversation about the ongoing revolt.

And now March is upon us.

The translations we present here explain why Chile’s autumn looks like it will be full of conflict—and why anarchists around the world should be paying attention. The first text, “For a Subversive, Anarcha-Feminist, Queer Month of March,” looks forward, setting the tone for a season of resistance and boldly proclaiming out-and-out anarchism. The second, “More than Two Months of Revolt against the Chilean State: First Impressions, Instinctive Predictions, and Non-Negotiables,” recapitulates what happened in the revolt up until the January-February summer vacations, and explores how it is both promising and challenging for anarchists.

Hot Summer and the Chilean Fall

The January-February summer vacations have seen the confrontations turn smaller and shorter, but there have still been significant developments. On January 28, in the middle of a week of student action against Chile’s university entrance exam, police ran over and murdered a soccer hooligan, Jorge “El Neco” Mora. As in October, this police violence compelled wider sectors of the oppressed to rise up alongside the students, looting supermarkets and attacking over 40 police stations in Santiago alone.

https://twitter.com/nobodypays/status/1222756978767933441

Last weekend, the coastal Viña del Mar International Song Festival—the oldest, largest, and arguably most prestigious music festival in Latin America—was rocked by riots outside its gates as well as demonstrations of solidarity inside the festival. Since October, the government has cancelled a number of international mega-events, including the COP 25, the APEC trade summit, the Copa Libertadores soccer championship, and Chile’s annual Teletón. It was a feat that the first international mega-event since October saw solidarity on stage, riots outside, and international artists and celebrities breathing tear gas in the luxury Hotel O’Higgins. What’s more, it is a sign that March will be fire.

https://twitter.com/crimethinc/status/1233024887347957760

https://twitter.com/_PuebloInforma/status/1232114076207271936

https://twitter.com/GatoDelPueblo/status/1232131750274502656

https://twitter.com/nobodypays/status/1231730323785965568

The March-April-May season in Chile is already known for its series of combative commemorative dates. In view of everything that has been going on since October, people have a lot of expectations this year. The calendar is packed:

- March 4-5: High school student protests on the first day of classes

- March 8: International Women’s Day

- March 9: Feminist general strike

- March 20: Mapuche march

- March 22: World Water Day, significant because of Chile’s privatization of water

- March 29: Day of the Young Combatant

- April 18: Six-month anniversary of October 18, the first night of looting and arsons against transportation infrastructure in Santiago

- April 26: Constitutional Plebiscite

- May 1: May Day

-

May 21: Navy Day, a national holiday celebrating Chile’s imperial conquest of the Peruvian and Bolivian coast in the 1883 War of the Pacific. Traditionally, the president gives an annual state-of-the-nation address on this day and people respond with violent protests in the coastal city of Valparaiso.

Anarcha-Feminists on the Frontline

Amid the countless calls circulating for action in March, one of the most significant is the call for anarcha-feminist and queer militancy.

On a visual level, anarchism-as-anarchism has been notably absent from much of the protests in Chile. The circle-A is widespread on walls and occasionally on signs, but as one interviewee put it in Radio Evasión 3, “There are also black and anarchist flags, but they are few. People are more concerned with other things than they are with carrying flags, because the confrontations are… well, let’s just say that if you’ve got a flag in your hands on the frontline instead of something else, you’re just asking to get shot.” There are a handful of anarchist assemblies, but (admittedly lacking hard numbers to back this claim up) we estimate that there are more self-described anarchists participating in neighborhood assemblies (many of which are anarchic in form) than in specifically self-identified anarchist assemblies.

The fact that the first wide-reaching, definitively anarchist call for action we know of in this revolt comes from anarcha-feminists attests to how popularly legitimate yet radical the Chilean feminist movement is. Perhaps the clearest confirmation of this is how widely popular the viciously anti-state “Un Violador En Tu Camino” song/dance by Las Tesis has become. This call for anarcha-feminist participation is a significant development in anarchist participation in the social revolt overall.

At a time when many in the North American left seem to be swapping out identity politics for class reductionism, the anarcha-feminist call to action in Chile is a reminder that resistance on every axis of oppression can offer points of departure for dismantling oppression and hierarchy as a whole. As the April 26 constitutional plebiscite approaches, it will be increasingly important for anarchists to emphasize visions and actions beyond participation in democracy, as the results of the plebiscite are sure to leave participants in the movement dissatisfied sooner or later. Lest fascists and the far right gain the opportunity to portray themselves as the only sector that consistently opposed the constitutional process—a process that will define a generation to come in Chile—anarchists must demonstrate that the misery of class stratification, the violence of police and prisons, and the lack of control over one’s life in society are not specific to any particular kind of constitution or government, but inherent in the state itself.

“FOR A SUBVERSIVE, ANARCHA-FEMINIST, QUEER MONTH OF MARCH. Patriarchy is the cornerstone of capitalist domination and the oppression, death, rape, and destruction that it generates. We are calling on you to escalate the already traditionally combative month of March. We are calling on you to support this fight, in all of its forms, against any institution and representation—symbolic or material—of patriarchal domination. We advocate for direct confrontation, without intermediaries, leaders, or representatives. AGAINST ALL AUTHORITY.”

“For a Subversive, Anarcha-Feminist, Queer Month of March”

Original text in Spanish here.

Society is structured by different chains of oppression that overlap and intersect, and we understand that we will only be able to do away with every one of them through radical confrontation. One of the primary anchors of these chains is patriarchy, which is why we are making a call for a subversive, anarcha-feminist, and queer month of March. Traditionally, March has been a combative month and we intend to maintain that tradition.

The destruction of authority, in its myriad dimensions, cannot be separated from questioning, challenging, and confronting cis-male domination in all its forms and effects. This is why we don’t see confrontation with patriarchy as a partial or single-issue struggle.

We are critical of the hegemonic views of liberal feminism that marginalize and exclude non-normative bodies and sexualities. Gender is an imposition, a social construct that we’re not interested in being a part of. We advocate for the complete deconstruction of how we see ourselves and relate to one another, without rules that govern who we can be.

Likewise, we do not see the struggle against patriarchy as separate or removed from anti-racist and anti-speciesist practice. The exercise of domination transverses all bodies and species, which is why any liberation must be total.

For the month of March, we call on all anti-authoritarian individuals and collectives to join in confronting any and every institution or representation, symbolic or material, that upholds, represents, or propagates cis-male domination. We will kick off this month of anti-patriarchal and anarchist struggle by taking to the streets—not to celebrate, nor to demand our “rights” or “equality.”

We are freely associated anti-authoritarians independent of any group, collective, or campaign that advocates reforming the current system of domination. We don’t demand anything from any institution. We’re not interested in “humane” capitalism. Regarding those who hold the monopoly on power and violence, we desire only their destruction. The changes in our lives only happen because of our own efforts, in which we mutually support one another as equals. We’re not interested in the kind of sisterhood of sympathizing with whoever happens to be a woman. Our solidarity is with the comrades who walk on the same side of the barricades with us. Social and psychological determinism based on gender is not all there is to comradeship. We immediately recognize those who choose to wield authority in any way, such as female cops or female judges, as our enemies—neither the social nor biological nor psychological conditions matter in this regard.

This March 8, we call on all the marginalized, on anyone alienated by reformist, pacifist, and liberal notions, to participate in a queer and anarcha-feminist black bloc. Let’s take the streets, fill them with anti-authoritarian action and propaganda, and defend beautiful and conscious uses of force.

Against the state and capital, struggle against patriarchy.

For total liberation, long live anarchy!

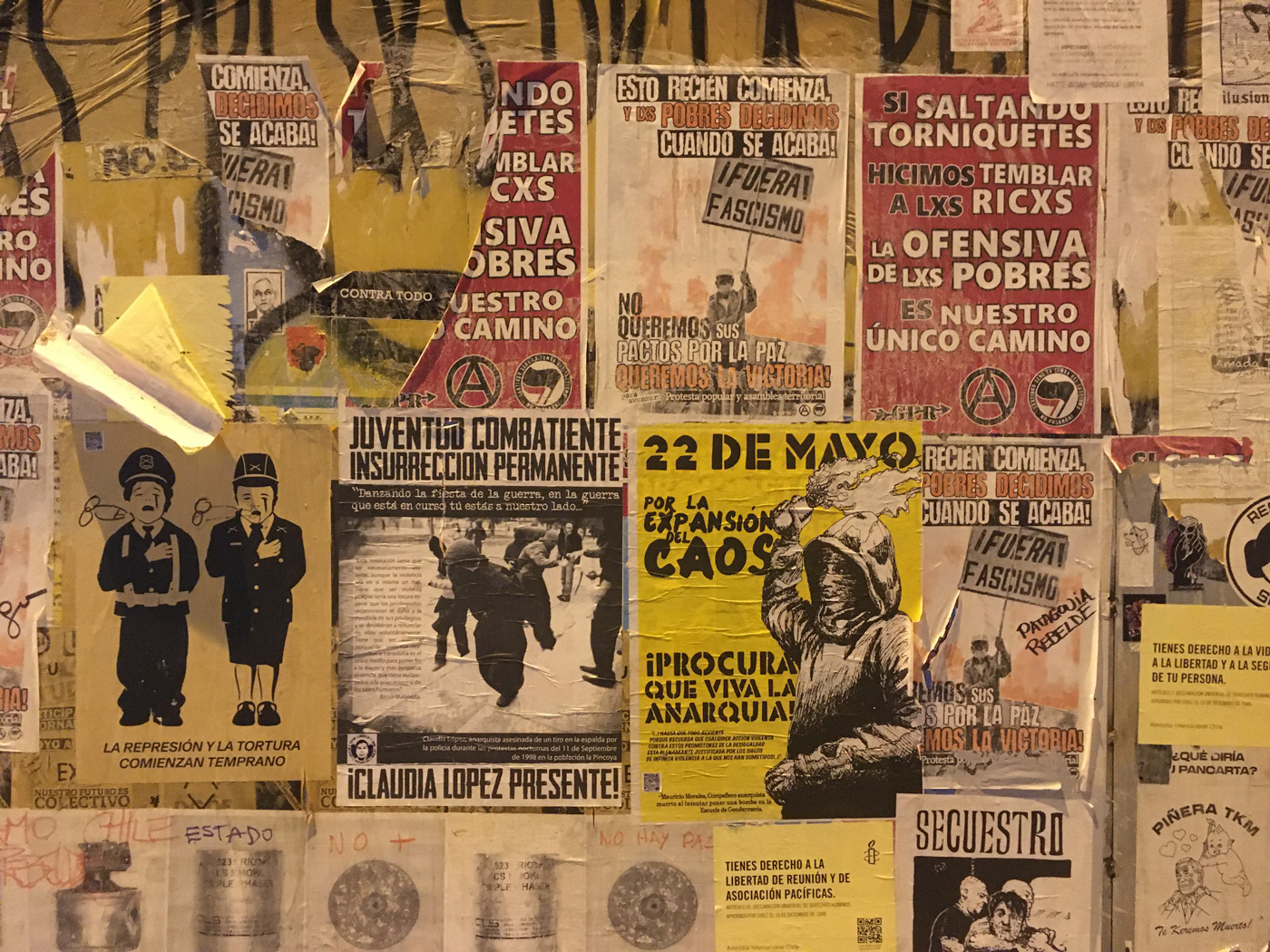

Anarchist propaganda on Alameda.

Popular Revolt: The Lay of the Land

Whether you’ve been following all of these developments closely, or are just getting acquainted with the months-long social revolt, the following text by the anarchist magazine Kalinov Most offers an excellent analysis of what aspects of the revolt are promising and challenging for anarchists. The Kalinov Most collective describes their publication as “a contribution towards the different debates and reflections that take place in anarchist and anti-authoritarian spaces, from a position that seeks to sharpen our ideas and practices of confrontation against domination.” Although the essay is over a month old, it comprehensively describes where things stood during the intermission between Round 1, during which the movement established that confrontation with the state is here to stay, and Round 2, when the upcoming Constitutional Plebiscite and electoralism in general will dominate the discussion of social issues.

The essay offers useful lessons for anarchists in all contexts: a healthy caution against romanticizing combat, a critique of the tendency to use conspiracy theories to explain disruptive acts [see appendix, below], and an analysis of leftist cooptation. The informal anarchist perspective behind the essay is “based on ideals of permanent conflict and the quest for individual liberty,” as they put it, but that does not mean they don’t promote collective efforts. Throughout the essay, they emphasize the need for spaces of encounter and interconnection. Lest readers mistake the idea of “permanent conflict” for simply continuing to endlessly protest without revolutionary ambitions, our translation team wants to emphasize that we were especially motivated to bring you this piece because, for perhaps the first time since Greece 2008, anarchists in the context of an ongoing social revolt are thinking practically about how to topple the state.

“…the need has arisen to experiment with the very real possibilities of weakening and eventually destroying the State. When all of the supermarkets in the area have been looted; when a large part of the transportation sector has been sabotaged; when the services of the state and capital simply do not work; when the fabric of society is torn and barely functions, how do we satisfy our needs? With whom? Among whom? In what way?”

Just as the Kalinov Most collective opts for a sober analysis instead of uncritical celebration, we want to temper hopes that the situation in Chile could become revolutionary. Still, the fact that revolutionary hopes are arising within us to the extent that we need to moderate them is itself remarkable, personally speaking. The last three years in the United States have seen a disheartening advance of authoritarianism—both on the right with Trumpist fascism and on the left with the troubling resurgence of authoritarian communism. The situation has become so bleak that, with revolution seemingly nowhere on the horizon, more than a few North American anarchists have turned to defending the Bernie Sanders campaign as a step forward.

Here, by contrast, there is a deep-seated distrust of the Chilean state in general, and against the promises of a new constitution that would increase social guarantees via the state—yes, the Bernie model—anarchists are continuing to push for destroying the state to open up more space for leaderless, horizontal relationships of mutual aid and solidarity, the forms of organization that have given the social movement in the streets the strength to persist up to the present moment.

Kalinov Most, an anarchist periodical.

“More than Two Months of Revolt against the Chilean State: First Impressions, Instinctive Predictions, and Non-Negotiables”

Original text in Spanish here.

“The passion for destruction is also a creative passion.” -Mikhail Bakunin

“Insurrection is a party. We take joy in the din of their defeat.” -Leon Czolgosz

The Ongoing Revolt: Days and Months of Conflict

The uprising that is currently rocking Chile is taking place without any official spokespeople or leadership to guide it. It goes on leaderless, self-organized, chaotic, and destructive; unstoppable despite the dead, injured, mutilated, and nearly two thousand new prisoners packed into Chile’s already crowded prisons. The spark of mass fare evasion in response to yet another increase in public transportation prices galvanized a broad spectrum of struggle and action against authority, culminating with all its force and vitality on October 18.

The aftershocks of those first days of upheaval are still felt—to a greater or lesser extent—daily, expressed in daring attacks on police stations and symbols of capitalism and in intense clashes with the Carabineros de Chile. Despite some wearing down (normal and understandable after more than 80 days of combat), the violent fight against authority is alive and well—and is becoming widely recognized as the most effective tool to dismantle state oppression, even among those who, until recently, would have condemned such behavior. We believe that this collective realization, along with the absence of any defined leadership, are, in one way or another, the key ingredients that have kept this uprising uncontrollable.

The anarchist presence in the different spheres of the confrontation is clear, and it has been from the day one. How could it not be—when this uprising is a massive and overwhelming expression of the same tactics of disobedience carried out and encouraged by anarchists for years upon years? How could it not be, being an uncontainable uprising without centralized leadership? How could it not be, when it is so completely in harmony with our constant calls for movement and action? The uprising is part of us because we are part of it; we feel completely at home in its destructive maelstrom, working to spread and intensify it wherever and however we can, far from and contrary to any attempt to domesticate or control it.

In the midst of months of revolt, we pause and take a deep breath of air (still poisoned with tear gas, mind you) to clarify a few things, to collect our thoughts, to venture a few predictions, and, of course, to assert our defiance.

Demonstration at Plaza de la Dignidad with an upside-down Chilean flag.

Street Fighting and Police Repression

This uprising represents both a continuity and an evolution of expressions of defiance against a world based on authority. We’ve seen the escalation of violence towards traditional power structures (financial institutions, political parties, and other symbols of authority), and of course against authoritarian security forces (military, police, under-cover agents, and the paramilitary gangs known as the Yellow Jackets1).

This generalization of defiance has broadened the arc of the street conflict, the practice of which didn’t start on October 18 [translator’s note: the first day of mass looting and transport arsons in Santiago], but which nevertheless has gone on amplifying and innovating its strategies in the heat of the revolt. The systematic and widespread use of shields, for example, only became necessary as a response to the enormous quantities of birdshot and tear gas fired indiscriminately at the bodies and faces of protesters, causing injuries and mutilations that have now been seen around the world. The multiformity of the movement is apparent in the wide variety of individual contributions to the conflict, made by each according to their abilities. Examples range from those who use laser pointers to blind security forces, to those who tear up the sidewalks for rocks to throw, to those who distribute food and water to those who are exhausted after hours of confrontation—all of this organized in a completely informal way in the heat of the battle for the streets.

This burgeoning political violence [translator’s note: against security forces] has been completely validated and legitimized during these days of conflict, with even the primera linea (frontline) being romanticized—something to perhaps be viewed with a certain amount of caution, given the tendency towards heroic exaltation of certain roles within the uprising that can lead to fetishism and militaristic mentalities.

The decentralized conflicts of the first days have given way to battles largely centered around downtown Santiago, central gathering spots in the poblaciones2 and in the plazas of other cities throughout Chile—battles which often turn into struggles for territory won from, or lost to, government forces.

A wide range of factors are contributing to the uprising; we do not fool ourselves by imagining that these anarchistic tendencies play a leading role above and beyond any other. Behind the goggles, gas-masks, and hoodies in the streets, we have seen the great variety of those who fuel the revolt, a mixture that fits quite well with the anarchic characterization we would make of the uprising: anti-authoritarian, leaderless, fostering horizontal relationships of mutual aid and solidarity. The idea of simple protest or making petty complaints has been clearly overtaken by a sensation of wanting to change absolutely everything, a feeling that may well be ephemeral—we can’t know how long it will last—but which is the very oxygen of the uprising at this moment.

The state has taken to its old ways with strategies and techniques drawn straight from the dictatorship, showing clearly how little it has changed. Worldwide coverage has shown many of these repressive tactics, from arrests, beatings, torture, rape, sexual abuse, lost eyes, and death in some circumstances (by gunshot or beatings, with the victims’ corpses thrown into burning businesses to pass them off as “looters,” or as having been trampled and suffocated).

We see the state making distressed and desperate calls for peace and unity among Chileans. Their attempts at pacification, however, have not had any meaningful result, and have not been able to quell the people’s rage and rejection of a broken normality. Their campaign for peace has been rendered ridiculous, as simply no one believes in or expects anything from those in authority anymore. Meanwhile, for their part, the political parties have unanimously agreed to draft a series of repressive laws that are being rushed through the legislative machinery.

If history is any lesson, we can expect the left to try to co-opt the uprising, reducing it to a handful of negotiable demands, to individual leaders or to the leadership of organizations. We have already seen unsuccessful attempts to employ this strategy from the group Unidad Social, comprised of various labor unions and political organizations. Despite their sad attempts to lead the protests, the streets have completely ignored them and continue to move to their own rhythm. If Unidad Social were to call for the end of the uprising and a return to normalcy today, absolutely no one would listen to them. Still, that isn’t to say that that those in the streets haven’t seized on any and every call for strikes and protest, regardless of whoever is behind the calls, to join in stronger and more combative days of action.

As a direct result of the uprising, new forms of collective action have arisen in the neighborhoods. Contentious and rife with contradiction, the asambleas territoriales [neighborhood assemblies] have become common spaces to argue for our ideas and approaches and to find each other in the upending of the old world.

Imposing normality: at the end of January, the police put heavy concrete barriers in front of the monument to fallen police offices. First these were covered with graffiti, then toppled. In effect, the police unwittingly built a trench for the primera linea, who previously had to make their own wall with shields. The only downside of the current concrete barriers is that police can shoot tear gas on the other side of them, where it’s risky for the primera linea to go.

The Neighborhood Assemblies: New Seeds Taking Root within the Revolt?

Born of the uprising, the neighborhood assemblies are on the one hand fascinating initiatives that provide an opportunity for self-organization and for invigorating territorial autonomy in all kinds of sectors, neighborhoods, and poblaciones throughout the country. However, on the other hand, the majority of these assemblies are currently calling for a constitutional process in order to replace the current constitution that has been in place since 1980. Political parties, social movement organizations, and labor unions that have been advocating for a constitutional process for years are taking advantage of the situation to try to position this process as the most important demand—in fact, the only demand—which would obviously mean a peaceful and civil resolution to the uprising, leading inevitably to a reestablishment of the state, and thus further strengthening it.

Similarly, we’ve encountered some political tendencies that look to transform the assemblies into “autonomous councils” to which authority would return as soon as it comes time to organize (or supplant) the “new society,” as well as tendencies that would like to have the assemblies converted into nothing more than transitional institutions prior to the formation of a “workers’ government.”

At this point, it becomes necessary to state in no uncertain terms that no anarchist group, assembly, federation, or organization is making or supporting the call for a constitutional process. There has not been a single word from the anarchist community suggesting that a new constitution would represent any kind of valid solution or a victory for the uprising, as was erroneously reported in recent weeks. To the contrary, these groups have explicitly positioned themselves against the constitutional process.

If our anarchist comrades can be found actively participating in the territorial assemblies (as they certainly can), it is in order to promote self-sufficiency and self-organization, with the goal of showing that we don’t need the state or capital to provide for our needs while at the same time making it clear that we currently find ourselves in a repressive situation in which it is impossible to escape the tentacles of authority. It is also to encourage and engage in anti-authoritarian action wherever we can—and not to demand a new constitution, a new panel, or a new council. Ultimately, any participation in the territorial assemblies is based on the never-ending quest to take control of our own lives, to find new ways of relating to each other, away from and contrary to those which have been imposed upon us. As anarchists, our involvement is based on ideals of permanent conflict and the quest for individual liberty—we don’t go to the assemblies to toe some line, nor do we confuse ourselves going down paths that are not our own. We also understand that these spaces are ever-changing, and that over time they may become institutional and authoritarian in nature, at which point we will find ourselves on the other side of the barricades from them.

Imposing normality: in mid-February the city government of Santiago painted over blocks of beautiful, inspiring, historically important art all along Alameda.

The Last Word Has Not Been Said: The Stage is Empty

This climactic, massive, and dynamic panorama—without leaders, without specific demands, and, thus far, not co-opted by the system—has been the stage on which we have moved and lived these last months. It goes on uninterrupted, though its intensity varies depending on current events and how worn out people are from the repression.

In an effort not to just fit the facts into preconceived notions, we constantly question our conclusions, weighing them against the insights of other comrades of other subversive inclinations in view of what is actually happening in the streets. By no means do we want to fall into self-serving fantasies or ridiculous conspiracy theories that see montajes [translator’s note: frame-ups or false flag operations, essentially state-fabricated criminal cases] all around us. For this reason we must be clear that not everything within the revolt is about rejecting and destroying the established order—there are social groups and movements involved in the uprising that are indeed part of the establishment and many others that, if they are not, wish to be. However, despite their various and constant attempts, these civic institutions have not managed to lead, centralize, or pacify the revolt in any way; a failure which is plainly evident, and in reference to which many anarchist groups are trying to force to a point of no return by using every kind of propaganda, in every orbit of the social upheaval, to focus on authority and all its tentacles as the enemy to destroy.

Our classic police poster alongside a mosaic portrait of Negro Matapacos on Alameda—a small contribution to the re-decoration of the walls after the mid-February paint job.

Blazing Paths of Destruction: Interpretations, Predictions, and Repudiations

This period of revolt has brought to light our weaknesses, which have perhaps been evident for years, but within the current context come into view much more clearly. The lack of connection, coordination, and communication between anarchist groups and spaces, particularly among those of us who opt for informality and constant opposition, brought about a failure to carry out any initiatives towards expanding the revolt, among other things—especially in the fist days of the uprising (October 18, 19, and 20). A previously consolidated coordination would have opened up new possibilities in the struggle given the context of the initial popular frenzy, when anything was possible and everything could be found at hand. The state had stumbled—and we should have been there to finish it off. Intensifying the offensive and occupying buildings are two out of a great many things we could have done more robustly. For this reason, we believe it is critical to create effective channels of communication and interaction between those of us who struggle for the destruction of authority.

In addition, a lack of anarchist spaces for meeting and engaging in activities aggravated this disconnection. Being able to count on stable spaces not only would have helped create more meetings (in spite of the sparse and weak communication that exists), it also could have served for preparing better propaganda, distributing resources, etc. Certainly, we would have had considerably greater opportunities to encourage dissent in the neighborhoods if such spaces had existed, though we cannot be sure to what extent state security forces would have tolerated their presence.

Nonetheless, in the revolt, we have seen a reaffirmation of the ideals and tactics that we have championed for years and that many comrades have gone to (and remain in) jail for. Specifically, we’re referring to our commitment to the destruction—here and now—of all that oppresses us, to unbridled and relentless resistance, to the generalizing and growth of street conflict—essentially, to everything we’ve lived and enjoyed on such a grand and continuous scale during these last months. We believe that this relentless anarchistic resistance has at last borne fruit, as seen in the wild student-led street conflicts of the last few years, all of which have been characterized by an undeniable anarchic sensibility reflected in their statements and actions. We have no doubt that this tireless and fierce student struggle was the direct predecessor of the October 18 uprising. The mass fare dodging that students called for, mobilized, and led was the unexpected spark of the revolt that we are now experiencing—an act that was actually preceded by months of conflict between police and students, primarily those from the Instituto Nacional, an emblematic school in the center of Santiago.

The fact that the revolt has continued to be chaotic and leaderless can be attributed to multiple factors and circumstances, a full analysis of which would far exceed the limits of this text; but the strong anarchist presence that vindicates the escalation and intensification of the revolt has played an important role in thwarting those who try to pacify or direct it. The antagonistic approach towards the state, expressed in the street fighting and in all the other aspects of this revolt, has blended harmoniously with the destructive spontaneity of the incited masses, which has in large part prevented any leaders from directing this uprising.

It’s reassuring that, throughout all of the informal anarchist efforts, our comrades have not been blinded by vanguardist pretensions, nor by ridiculous attempts to form some grand organization capable of leading the uprising. This contrasts with the tired voices of ex-members of extreme-left political groups who long for a past when they were the leaders and the only dissident voices. As anarchists, we understand very well that we are only a part of this revolt, neither above nor below anyone else, and that working to strengthen the uprising does not mean that we want to lead it—on the contrary, among other things, it means resisting those who try to lead it, because we know that this [the consolidation of leadership in any particular set of hands] would spell the end of the revolt.

The situation for our comrades who were in prison before the uprising has been further complicated by potential transfers and the imposition of laws that have created even more obstacles to their release. It is true that there have not yet been prison riots in this revolt, but it is also true that freeing prisoners has always been a priority in all uprisings, and this one should be no exception, precisely because they are the ones we need most in the streets.

The lessons and challenges are many, and they occur every day of conflict, in each moment of rest by the flames of the barricades or walking the streets of the city. The speculation about possible outcomes seems endless; one can hear it in conversations in chance encounters or in any neighborhood concert, assembly, or cook out. These are the urgent lessons that we want to share with our comrades from every locale and in all social contexts, lessons that branch out into discussion about the possibilities of the ongoing conflict.

Within the more informal anarchist tendencies, we have been working for years to raise awareness of the need for free association and affinity groups—and we have continued those practices in different facets of the uprising. These ways of organizing ourselves are the most consistent and coherent with our principals, and they allow us to realize our potential as individuals within a collective united by a sincere will, without limiting or coercive structures.

Over the course of the revolt, there have been several initiatives in the neighborhoods and poblaciones, all working to extend the conflict and recover autonomy. The territorial dimension of the uprising plays an important role not only in taking on the state and its control, but also in promoting survival initiatives that are antagonistic to the old world. So we’re left with a few questions: How best to blend the idea of affinity with the perspectives in the neighborhoods, where community is largely based on geographic location? Where do these perspectives intersect and where do they diverge? Can we afford to ignore these neighborhood initiatives or to put all of our energy into these spaces? These are not merely questions for theoretical discussion, but rather of the utmost practicality in the day-to-day aspects of the uprising.

When the state begins to falter, questions like these or about opportunities for self-determination and autonomy lead us to the arguments at the root of anarchist visions. Those old debates, which we so often avoided because they seemed full of nothing but promises of a future revolution, are actually contemporary and urgent when we see them through the lens of constant resistance. The pulse of the uprising confirms this, demands it.

Among those of us who search for the effective destruction of authority and not just a dynamic of routine protest, the need has arisen to experiment with the very real possibilities of weakening and eventually destroying the State. When all of the supermarkets in the area have been looted; when a large part of the transportation sector has been sabotaged; when the services of the state and capital simply do not work; when the fabric of society is torn and barely functions, how do we satisfy our needs? With whom? Among whom? In what way?

It is at this point that we return to the essence of the anarchist struggle in the destructive/creative process. We understand that destruction and creation occur in unison: they cannot be thought of as two distinct stages, but rather evolve together simultaneously. On a deeper level, the youths that decide to destroy a bank office are not only breaking a few windows or reducing the place to ashes; beyond simply destroying a symbol, at the same time they are creating a different way of understanding the use of force, of normality, of urbanization, of life itself and the various ways to confront oppression. Clearly this is not just about making more (or, for the state, less) broken windows—it’s about a choice between social relationships of free association or relationships of structural domination, and in this way the revolt creates conditions of willingness, creativity, imagination, and a vitality unknown in the world ordered by authority. We have lived and felt it within ourselves, in conversations, in dialogues, and in the bonds that people are constantly forging.

From individual acts to the development of generalized revolt, the destruction of both material structures and of relations of authority brings with it, almost instinctively, the rejection of the status quo and an openness to the possibilities of new ways of understanding the world. It is in this domain that we must work to strengthen these emerging possibilities, to carry them into practice, to give them material form in order to survive and attack.

We have always offered sharp critiques of bubbles of liberty, and this essay will be no exception. We understand that in the scenes of this pervasive revolt, of the fracturing and rupturing of the state, it is the conflict itself that brings us back to questions of how to live our daily lives in a way that is adversarial to authority. We know that the answers do not lie in some alternative lifestyle or mere coexistence, but in the organization of combative practices in open opposition to the world of power. Discussions about the expansion of territorial self-determination in small communities and confrontation with authority in general resound in conversations throughout the revolt. We can learn from past experiences, but we need to keep them current and relevant.

We have always held that our means should be in direct accordance with our ends. Therefore, from an informal anarchist point of view, allow us to daydream as we review the present situation. What are our ends? We are committed to the free association of small communities thath support and provide for each other without permanent power structures over individuals, to maintain constant tension and to always be questioning, to never believe in a final or finalized state of being. Our present actions should be directed towards these ends.

The uprising is continuously opening up new discussions, and these are not just scripted dialogues—we are living through the process of discussion and it has real consequences for our lives. Again, we ask ourselves what the limits of this uprising are, and how to transform it into the total collapse of the state and the reign of authority, how to bring down the entire establishment. The revolt shows us our own limits—not the limits of a lack of specific organization, structure, or plan, but rather the limits of our own ability to tear down the old world and to expand and defend anti-authoritarian ways of being.

What else can we be doing? What else can we provide? The streets have not stopped burning and the conflict has taken on a life of its own, growing and intensifying with each passing day. Far from longing for militant political parties that we can rely on to fight for us, we believe revolutions have a force and rhythm of their own, and perhaps the uprisings of the 21st century have dynamics that we are still just exploring and getting to know. We must leave aside those who sadly see the hand of the state behind the first acts of the uprising and those who dismiss the reality we are living as some “mock revolution,” those with defeatist attitudes and a sterile, structured view of the revolutionary process. These attitudes will be remembered as nothing more than anecdotes lost to the flames of the revolt, to the destruction of symbols of power, in what is without doubt one of the most important political and historical moments for anarchist expression in generations—not only for Chile, but for the world at large.

The streets are still burning, hundreds of eyes are still being blinded by uniformed hitmen, blood still stains the walls of the police stations, and hundreds of prisoners are facing prison for the first time. The smell of petrol and tear gas, the sound of the explosions, the color of the flames and the laser pointers mix with the statues and monuments tumbled to the ground. Every day, everywhere, there dawns a new day of revolt—even when exhaustion takes its toll and fighting becomes sporadic. Thus far, the authorities have absolutely failed to impose order or normalcy, while we as dissidents have not yet been able to completely overturn it. This is a work in progress, unfolding at this very moment—as these words are written new initiatives for insubordination and insurrection are being born.

We remain with and for all.

Because the revolution is alive: Long live the reproducible and contagious revolution!

-Kalinov Most / Chilean region

January 2020

A small tent city occupying the ruins of a former bank just around the corner from Plaza de la Dignidad, the survival of which is made possible by the primera linea.

Appendix: Communiqués and Conspiracy Theories

More and more, anarchists in Chile are publicly criticizing the tendency to assume that any significantly disruptive or destructive act without a credible communiqué must be a plot conspired by the state. Part of this focus on communiqués—and, as some anarchists in Chile argue, part of the doubt that ordinary people could radicalize so quickly as to, say, begin burning metro stations—stems from the legacy of the armed guerrilla organizations that fought against the Pinochet dictatorship. Currently, instead of frank and honest discussions about tactics and strategy, ideological differences between distinct currents within the revolt are often expressed through accusations that certain behavior is the work of state actors.

In the best light, this can be seen as the result of comrades on the street not wishing to create divisions in the movement. It can also be risky to speak frankly about which kinds of militant applications of force one endorses. On the other hand, there are certainly some comrades who find it more comfortable to describe anything that might stain the movement as a state-fabricated conspiracy rather than reckoning with the messiness of a four-month long insurrection in a country with one of the most dramatic proportions of wealth inequality in the world.

Here’s what the February/March 2020 edition of the anarchist periodical Confrontación has to say about the matter:

Montajes

For quite a while now, we have been seeing the accusations on social media that such and such violent action, be it an individual action or with mass participation, was a state-fabricated plot, a montaje. They say that the huge fire on the ENEL building was a montaje; that the arsons of the Metro stations have traits of false-flag operations; that the torching of this or that church was a montaje; that undercover cops threw that Molotov, and so on and so on.

While thousands of people march and struggle in the streets, some people seriously seem to think that any uncontrollable action must be the work of some obscure apparatus of the state. There are even comrades from revolutionary and leftist tendencies that end up parroting the line that this or that violent action was an obvious conspiracy.

At the end of the day, this way of looking at the world only feeds the false notion that the state is omnipotent and that nobody can escape its panoptic, limitless surveillance.

Of course, we are happy to discuss the revolutionary character of any particular action or attack, its efficacy or its consequences for the exploited class. We’re even up for criticizing the indiscriminate romanticization of violence, but from to go from there to saying that every attack, act of looting, or incidence of propaganda by the deed must have been cooked up by the police—that is a disastrous step that must not be taken, as we will continue to argue.

It’s not that we are so naïve as to reject a priori the possibility that the intelligence apparatuses of the state are capable of provoking certain destabilizing acts with the goal of taking advantage of them, but it’s another thing to overlook the capacity, will, and autonomy that people have to carry out all sorts of actions, including those of violent protest.

This is why we question the idea of taking conspiracy theories and false-flag actions as the primary explanation for the violent acts of protest that occurred at the beginning of the social upheaval on October 18—because the recognition of individual autonomy that we claim for ourselves is something that we extend to others as well.

For freedom, anarchy, and the defense of our autonomy.

Anarchy in the streets! The intersection of Alameda with Santa Rosa, one of the busiest intersections in downtown Santiago, has been without a traffic light for months. Anarchy works.

-

In this context, the term “Yellow Jackets” has nothing to do with the Yellow Vest movement in France. In this case, groups of organized citizens who have decided to protect the interests and infrastructure of capital and the state in their neighborhoods identify themselves with this term. ↩

-

The connotation of the term población requires more Chilean history than we can include here; suffice it to say that the poblaciones are ghettos that began as land occupations and shantytowns. Most have been developed in Santiago, but many poblaciones throughout Chile are still essentially shanties, or slums. The history of the poblas also carries a connotation of self-organization and experiences of autonomy from the state. In the simplest translation of the word, población can be understood as “ghetto.” For a more extensive history of the poblaciones, check out episode 29 of The Ex-Worker podcast. ↩