On the occasion of March 8, International Women’s Day, Somayeh Rostampour explores the origins and implications of the slogan that became the watchword of the uprising in Iran in 2022.

Preface

The revolutionary uprising associated with the slogan “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” (“Woman, Life, Freedom”) began in Iran almost six months ago, on September 16, 2022, when the morality police of the Islamic Republic murdered a 22-year-old Kurdish woman, Jina (Mahsa) Amini. Since then, the whole country has been on fire. This feminist revolution is not simply a response to compulsory hijab; it aims to put an end to 44 years of gender apartheid, patriarchy, military dictatorship, neoliberalism, nationalism, and Islamist theocracy. Like the so-called Arab Spring, the Jin, Jiyan, Azadi movement demands “the fall of the regime” with an eye toward systemic social change.

During the first three months of the movement, more than 18,000 activists and protesters were arrested, thousands were injured, and more than 500 people were shot dead or killed during torture, including 70 children. More than 100 people still face the risk of execution. Prisoners have been subjected to various forms of brutality, including baseless verdicts in show trials conducted without independent lawyers and physical and psychological torture aimed at forcing captives to sign false confessions. Women and queer prisoners in particular face the threats of rape and sexual harassment. In the most recent phase of repression, the regime is taking revenge on the women’s insurrection by systematically poisoning female students and children with chemical gas in more than 200 schools across the country, resulted in the death of at least two children and the hospitalization of hundreds more.

Despite this, or because of it, the movement lives on. The oppressed classes continue to fight on the street, in prisons and schools, at work, on social media platforms, in the commemoration of martyrs during funeral ceremonies and in solidarity with mothers and families who have lost their children. The Islamic Republic has reached an irreversible point; the wheels of history cannot be turned backwards by repression. When young women in universities chant, “This is a women’s revolution, do not call it a protest anymore,” they mean that “This time is different,” that they are determined to overthrow the regime. Currently, the rhythm of street protests is reduced; militants have used this interval as an opportunity to organize recover, and reflect.

The following article was originally published in Persian on October 27, 2022, during the initial phases of the movement. It was translated from Persian to English by Golnar Narimani and compared with the translation of an anonymous comrade. The text is edited and finalized by Morteza Samanpour. I am grateful to all of them as well as the editorial board of CrimethInc. for making this lengthy text available for English readers.

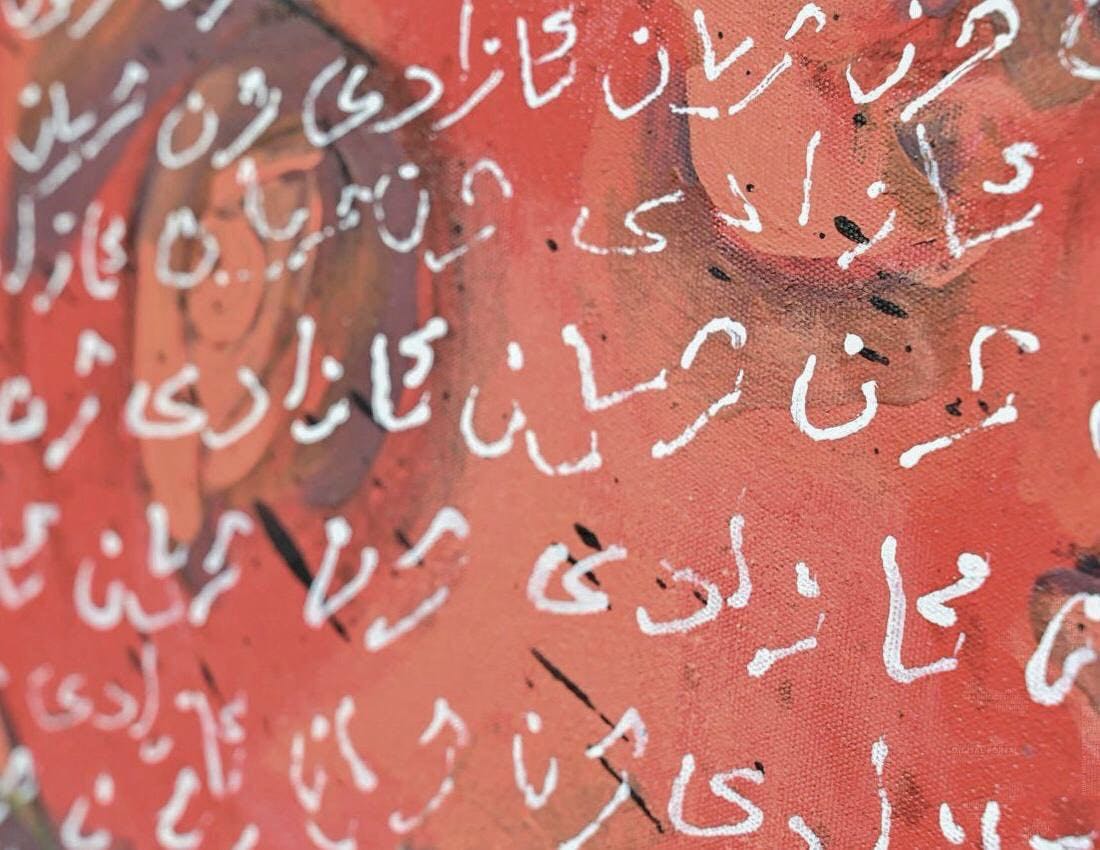

Jin, Jiyan, Azad (“Woman, Life, Freedom”) in Kurdish.

Introduction

After the so-called “morality police” murdered Jina Amini on September 16, 2022, “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” rapidly became the central slogan for a wave of protests that spread all over Iran. The slogan was chanted for the first time on the day of Jina’s burial by the angry people of Saqqez, her home city in Kurdistan: thousands of courageous people expressed solidarity with her family and ruined the regime’s plan to bury Jina in secret.

As a part of their political culture, Kurdish people collectively celebrate martyrdom at the funerals of militants who sacrificed their lives, transforming death into a weapon of resistance. On the day of Jina’s burial, someone shouted “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi,” which everyone else immediately repeated, according to a woman who witnessed that event. The slogan was clear, familiar, and intuitively understandable by heart. This slogan was then used in Sanandaj, another Kurdish city, and then by students in Tehran, finally spreading throughout the country to every city, village, and street.

How did this slogan come to Saqqez in the first place? Why did it become the central slogan of different parts of Kurdistan and the rest of Iran? How did it become the name via which the revolutionary movement in Iran identifies itself? What social and political meanings can the genealogy of the slogan reveal?

The Kurdish-controlled city of Qamishli in northeastern Syria (Rojava) on September 26, 2022. Women burn headscarves to support of women’s uprising in Iran.

The Historical Origins of “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” (Woman, Life, Freedom)

The slogan “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” did not become the watchword of the uprising in Iran by accident. It did not fall from the sky; it emerged from a long history of social struggles. This slogan is the legacy of the Kurdish women’s movement in the part of Kurdistan that lies in Turkey, an area known to Kurds as “Bakur.”

In September 2022, Atefeh Nabavii, a fellow inmate of Shirin Alamholi (a member of PJAK, the Kurdish Iranian branch of the PKK), wrote on her Twitter:

“It was Shirin Alamholi from whom I first heard the slogan of “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” in Evin Prison; it was written on the wall, next to her bed.

Shirin Alamholi was executed in May 2009 for being a member of PJAK, considered a “terrorist” party by the regime. She was only 28 years old; they never returned her body to her family.

Both the PJAK in Rojhilat (the part of Kurdistan in Iran) and the Kurdish women’s movement in Bakur are influenced by the political philosophy of Abdullah Öcalan, the founder and charismatic leader of Kurdistan’s Workers’ Party (PKK). Öcalan founded the party in 1978 with a small group of his comrades; following the repressive military coup of 1980, the party put armed struggle on its agenda in 1984 and has become the most important opposition force in Turkey since then. Öcalan has been in solitary confinement since 1999, locked in İmralı prison on an island near Istanbul. In his Marxist and nationalist phase, Öcalan tried to interweave the ideas of Mao Tse-Tung and Frantz Fanon with the demand for Kurdish liberation in order to form a united socialist movement. Right from the beginning, he encouraged women to participate in Kurdistan’s national movement with the principal slogan that “the liberation of Kurdistan is not possible without women’s liberation.”1

With this slogan, the PKK distinguished itself from other leftist organizations of that time in Turkey and the Middle East more generally. The PKK highlighted the question of women within the framework of modern Kurdish nationalism, which was mostly intertwined with preserving the homeland, one’s own soil, and the Kurdish culture and language.

A photograph of Jina (Mahsa) Amini in Kurdish attire.

However, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, from 1995 onwards the PKK went through an intellectual revolution. It began to move away from orthodox Marxism and the demand for an independent Kurdish state, abandoning the idea of “Great Kurdistan,” and moved towards political ideas centered around “democracy” rather than “class” in the classical Marxist sense of the term. In this new phase of the Kurdish movement led by the PKK, political subjectivity is not identified only with workers as a “vanguard,” but also with women and ecological activists. This trend reached its peak following Öcalan’s arrest and the texts he published from Turkey’s prison as a court defence. In these books, written under desperate conditions and sent to his followers by fax as well as his lawyers, Öcalan leans towards a form of council self-government called “democratic confederalism” constituted of three main pillars: “communes, women, and ecology.”2 In this new phase, the question of women became central to the PKK and the women’s movement of the party gained increasing independence, both practically and theoretically.3

In the first phase of the PKK, when nationalist and Marxist-Leninist ideas prevailed, Öcalan referred to the ancient mythologies of Mesopotamia (the historical region of Western Asia that includes the geographical inhabitants of Kurdish people and others), framing it as the “glorious ancient past” of the Kurds and proposing that Mesopotamian societies were matriarchal during that time.4

Öcalan employed local and feminine myths against the histories of imperialism, colonialism, and patriarchy. Highlighting the mythical antagonism between Enkidu (the masculine god) as the embodiment of the state and Ishtar (the goddess of war, romantic love, and feminine freedom) as incarnated in women guerrillas, Öcalan tried to encourage Kurdish women to join armed struggle. In this theoretical framework, women are considered to be the first to create life and cultivate the knowledge and tools for living, which were later stolen from the goddesses by men.

Öcalan associated women’s creative powers with their unique capability of motherhood and childbirth, i.e., their distinctive bodily and physiological features. This is where part of his framework ties the superiority of women with their distinctive physical characteristics in an essentialist way, and in his interpretation of gender, a mythological and immaterial approach replaces a materialistic approach. The goal, however, was clearly political. As Öcalan himself stated, his aim was to give back to women their lost self-confidence and to show that patriarchy was not an eternal and natural principle of history but the result of historical practices.5 Patriarchy, therefore, can be transformed. In other words, because a world based on gender equality had existed in Mesopotamia once, it could have been realized again.

In Turkey, Kurdish women took to the streets of Istanbul, Ankara, and Adana to protest the killing of Jina Amini.

Starting in the 1990s, especially in the years 1994 to 1998, Öcalan used “Woman” and “Life” together many times. Especially because the root of the words woman (Jin) and life (Jiyan) are the same in Kurdish, the use of women and life together was easily diffused in Kurdistan. For instance, in 1999, the PKK published a booklet titled “Jin Jyian” (“Women-Life”), and from around 2000 onwards, the slogan “Jin, Jiyan” was widely used by the Kuridish women’s movements in Bakur. The expression “woman-life” (Jin, Jiyan) is much older than “Jin, Jyian, Azadi” (“Woman, life, freedom”).

Freedom (Azadi) is also one of the PKK keywords in the context of gender. In fact, it was the idea of “women’s freedom” that initially mobilized them to participate in political action as well as armed struggle. According to the PKK, “freedom” is the liberation of women from power relations and domination—specifically from capitalism, the state, and patriarchy (including the institution of the family). For instance, in the first conference held in Istanbul (in 1999) by Kurdish activists in support of the PKK, the slogan “Woman is free, homeland is free” played a central role.

As part of the larger process via which Öcalan’s thought transformed in prison, he used these three words together for the first time in the fourth volume of his prison writings, The Civilizational Crisis in the Middle East and the Democratic Civilization Solution (2016). But until 2008, its use was very limited. It was from 2013 onwards that the slogan was heard in Rojava and Bakur, spreading to other parts of Kurdistan. In a letter written in 2013, Öcalan underlined the political power of the slogan “Jin, Jyian, Azadi” in pursuing a “dignified life” and creating a utopian society. Curiously, Öcalan called the slogan a “magical formula” for women’s revolution in the Middle East that should be a model for the women of Rojava and all Middle Eastern women.6 Today, the slogan is chanted by women in numerous cities of Latin America, Europe and the United States.

January 2, 2023: the commemoration ceremony of the 40th day of the martyrdom of one of the martyrs of the Kurdish city of Mahabad.

However, neither the history of the PKK, nor the history of women in this movement, nor the history of this slogan can be reduced to its leader. The PKK is both a social and a political movement that has found its way not only into politics but also into the daily lives of millions of people across successive generations. The PKK cannot ideologically control the political scene of Kurdistan however it wishes to, because in the end, the actions of political subjects determine the fate of ideas—whether they are accepted, consolidated, and promoted or rejected and abandoned.

PKK women (both guerrillas and civil activists) are the subjects who have made “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” the pivotal idea of the movement. Their simultaneous struggle against both the nationalist patriarchy of the Turkish state and patriarchy within the party itself has been a great historical achievement, a source of inspiration for us Kurdish women and for women in the region and around the world. Especially after 1995, they carried out a range of endeavors, making numerous sacrifices and performing many experiments. While it is beyond the scope of this text to provide a detailed history of the PKK’s women’s movement, it should be pointed out that it was women who “feminized” politics in Kurdistan and dramatically transformed it in Turkey.7 The fact that the party’s new ideology placed women at the center was surely influential, but it was women’s conscious political actions and their intersectional fights against capital and the state (which is the symbol of patriarchy, according to the PKK) that caused the slogans to be popularized and to travel across borders.

Activists who sought to deal with violence against women in Bakur played a commendable role. They established various institutions to fight against violence; they themselves carried the coffins of women who were killed due to violence and buried them with their slogans, songs, and feminine ululation. They were connected with “ordinary” women, going from door to door and from neighbourhood to neighbourhood in order to change the question of gender from a concern of “elites” to an issue concerning all of the oppressed. By criticizing elitist feminism, they were able to make women’s issues relevant to all classes of society.

According to one of the women I interviewed, in 2002, during a ceremony held by female PKK supporters for the burial of a woman who lost her life in a so-called “honor killing,” the women chanted “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi.” Some activists referred to these victims as “martyrs.” Later, this became a widespread political tradition among PKK supporters.

More recently, in Bakur and especially Rojava, women who were victims of domestic violence or were killed by the Turkish state and ISIS have been buried with the slogan “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi.”

The funeral ceremony of Jina Amini in Saqqez, where the slogan “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” was chanted by women who took off their headscarves as an act of protest against the compulsory hijab.

Therefore, what happened on September 17, 2022 in Saqqez during the burial of Jina Amini was not a new and unprecedented event. Rather it was the continuation of a longstanding political tradition that emerged from the PKK and had become a revolutionary tradition in various parts of Kurdistan. Jina’s burial became a demonstration in the cemetery in Saqqez precisely because of this tradition of politicizing death that has been practiced for years in Bakur and Rojava, which has been inspiring for Kurds in Iran.

Dadkhaah mothers of Kurdistan, the justice seekers who lost their loved ones, also played a pivotal role in spreading “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” in Bakur. They succeeded in removing woman-life from its essentialist associations and giving it a more political meaning. These mothers acted as Kurdistan’s memory defying oblivion and death. They challenged the deaths of their loved ones by politicizing justice, thus becoming political subjects and messengers of “life.” In a movement that has experienced more than 40,000 casualties so far in its fight against the fascistic Turkish state, Dadkhaah mothers have been the pioneers of peace, especially those justice-seeking mothers who lost their children in the fight against the Turkish state and could not even bury their bodies.

One of the key groups among those seeking justice in the part of Kurdistan in Turkey is the “Mothers of Saturday.” They protested every Saturday in Galatasaray Square from 1995 to 1999 for 200 weeks, seeking justice for their disappeared children—who were among over 17,000 victims. After they were repressed, the “Mothers of Reconciliation” continued organizing from 2008 on with the aim of raising awareness towards a peaceful solution to the Kurds’ issues. They came from various social classes; most of them had little education and worked in various cities in Kurdistan. For example, one of the members of Mothers of Peace (Makbulaa) who had lost her children participated in international gatherings despite never having attended a school.

Both Mothers of Saturday and Mothers of Peace used the slogan “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” in their protests in different ways. Thanks to them, starting in 2006, the slogan made its way to the demonstrations in Turkey observing International Women’s Day on March 8, and then to Rojava from 2012 onwards.

Kurdish women demonstrate during International Women’s Day celebrations in Diyarbakir, Turkey, on March 10, 2007. Their signs read “Woman, life, freedom,” “Long live March 8,” “No to the massacres of women” and “No to harassment and rape.”

Thousands of mothers who have become political activists due to tragic and brutal oppression in the part of Kurdistan that lies in Turkey are increasingly politicizing their daily lives across both private and public spaces. This represents another similarity with the situation in Iran. Private affairs under the yoke of oppression have created a deep crisis that inevitably spreads to public spheres, so that the two mutually transform each other. Understanding these similarities, we can identify the multiple significations of Jin, Jiyan, Azadi in a transnational context.

The justice-seeking mothers sought to occupy public space in their own way during these protests and especially at funerals, through ululation (Zılgıt), expressions of joy, and collective Kurdish dances through which they turned non-political male-dominated spaces into women’s political spaces.

The justice-seeking mothers’ struggles soon crossed the Turkish border, spreading further with the revolution in Rojava and in response to the murders of three women who were PKK members in Paris in 2013.8 The coinciding of these assassinations with the participation of women activists in what is called the “Rojava Women’s Revolution” gave women’s issues such as femicide more prominence in politics throughout Kurdistan. The YPJ (Women’s Protection Units) increasingly employed the slogan “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” at the burials of women martyrs who fought against the Islamic State. Consequently, the slogan became a symbol of struggle and sacrifice in the effort to build a new woman-centered society. More recently, this slogan has become a weapon of resistance against any form of violence; it especially symbolizes the celebration of life against the everyday murder of women due to their gender.9

So this slogan is the fruit of over four decades of relentless struggle against all forms of authoritarianism, capitalism, colonialism, foreign interventions, nationalist and quasi-colonial governments, political Islam, religious extremism, and sexual socio-political violence. Now, it has passed beyond the local borders, becoming a source of inspiration not only for leftist activists who value women’s revolutionary struggles but also for women across various geographies who have had similar experiences. In 2020, Catalan and Spanish women who had travelled to Rojava published a book about women’s movement in Kurdistan, titled “Mujer, Vida, Libertad” (Jin, Jiyan, Azadi).

Demonstrations in Europe in solidarity with the Kurdish women’s movement in Turkey.

This slogan has had a life of its own, finding new meanings in different geographies. For example, from 2014 until now, during the March 8 protests in France, “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” has been heard in some left blocs; some feminists have adjusted it to the new combination “Women, Struggle, Freedom” [Femmes, Lutte, Liberté] to make it more inclusive. They made “woman” plural in order to integrate a diversity of sexual orientations, and replaced “life” with “struggle” because the word “life” could lock women into naturalistic biological roles, according to some interpretations. Others believe that this slogan does not suffice to express women’s demands, because it does not identify class oppression.

In relation to the Jina Uprising in Iran, it is vital to acknowledge the roots of this slogan from a feminist perspective because it makes visible the women of the PKK who created the slogan, women who have been marginalized as political subjects by the apparatus of both state and non-state nationalism as well as by the PKK’s rivals in Kurdistan. This affirms their feminist struggles and helps us to challenge the right-wing appropriation of “Jina, Jiyan, Azadi” by both Kurdish and non-Kurdish parties. Emphasizing the roots of this slogan also reflects the distinct history of the men and women within the PKK. This history is ignored by most of the PKK’s rivals in Iran and Kurdistan (especially by masculine institutions and parties), because they only seek to win political competitions, not to bring about the liberation of women and gender equality.

This denial also makes it more difficult to identify the similarities between PKK women and other Kurdish and Middle Eastern women in the region, quite apart from the PKK as a political party. In fact, the shared experience of patriarchal oppression under authoritarian governments and patriarchal society connects the Kurdish women’s movement in Bakur and Rojava and their slogan “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” to the struggles of other women in the region—today in Iran and tomorrow in other countries. This is why we have seen women in Bakur and Rojava carry out many solidarity actions with women in Iran over the past five months.

The Kurdish city of Saqqez, Jina’s home city, marking 40 days since she died in custody.

Turkey may not be considered authoritarian for many Turkish citizens, but the Kurds have always experienced it as an authoritarian state, where even the use of the words “Kurd” and “Kurdistan” or the letters that are in the Kurdish alphabet but not in Turkish (Q, W, X) were considered as a crime from the beginning of the twentieth century until very recently. After the Turkish state militarized Diyarbakır (considered by many Kurdish people to be the capital of Turkey), mayor Cemal Gürsel stated “There are no Kurds in this country. Whoever says he is a Kurd, I will spit in his face.” This shows the similarities between the authoritarian structure of the Turkish state in the part of Kurdistan ruled by Turkey—a state which has always exposed Kurdish people to the threat of genocide and massacre—and the despotic Iranian dictatorship. These similarities are becoming more evident with the rise of the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi) in Turkey and the attempt to recode gender questions according to Islamic doctrines.

This has also brought about similarities between the struggles in Turkey and Iran. The spread of the slogan “Women Life Freedom” is as much the product of cross-border inspiration as the result of political traditions in Rojhilat (the part of Kurdistan in Iran). The magnificent performance of the Kurdish women on the day of Jina’s funeral in Kurdistan (the starting point of the revolutionary uprising of 2022), in which they waved their headscarves and turned the symbol of state oppression into a flag of feminist struggle, was the outcome of a longstanding history of struggles, resistance, and political organization in Rohjilat.

October 29, 2022: the Kurdish city of Mahabad.

This has been handed down from one generation to the next despite brutal state repression. From the Republic of Kurdistan in Mahabad (1946) to the 1979 Revolution, from the social dynamics of Kurdish society to the activities of political parties with the slogan “democracy for Iran and autonomy for Kurdistan,” involving popular councils in some cases, this political tradition has established a kind of radicalism in Kurdistan, the legacy of which has reached today’s youth. The seeds of these collectives and political movements, most of which belonged to the left, were buried with the rise of counterrevolutionary movement of Islamist forces in the 1979 revolution.

These movements were among the first to fight against the Islamic Republic’s announcement of mandatory hijab in 1979, pushing back against sexist and nationalist narratives amid the many intersecting fields of oppression and exploitation that Kurdish women face. In some cities of Kurdistan (Sanandaj, Marivan, and Kermanshah), thousands of women demonstrated on the occasion of the 8th of March to protest against the mandatory hijab in Iran. Like their sisters in other cities, they chanted the same slogans that were heard during the 2022 uprising: “No to mandatory hijab, no to humiliation, death to the dictatorship.” This has entrenched a radical tradition around March 8th in Iranian Kurdistan.

The power vacuum caused by the fall of the dictatorial Pahlavi regime also led to the formation of women’s organizations. In the midst of opening up this political space, for the first time in the history of the Kurdish people’s struggle, even before the PKK, a group of revolutionary women from Kurdistan took up arms and joined the ranks of Komala’s Peshmerga force (1979-1991), a Maoist party.10 During and because of these struggles, numerous independent and mainly leftist women’s organizations were established in 1979-1980, including the “(Kurdish) Women’s Council of Sanandaj,” the “Women’s Union of Marivan,” and the “Community of Women Activists of Saqqez.” Despite repression, activists in Kurdistan, especially socialists, continued along this path over the following years, struggling against inequalities imposed along the lines of gender, ethnicity, and class.

November 19, 2022: protesters barricading the Kurdish city of Mahabad while listening to a famous Kurdish political song associated with a socialist party (Komala), composed shortly after the 1979 revolution.

The Time Has Come!

While during 1980s and 1990s, Turkish nationalists (both in the government and in political movements) denied the existence of Kurdish question and Kurdish nationalists deprioritized women’s issues, the PKK emphasized the question of gender. In the 1980s and 1990s, these organizations were often influenced by anti-imperialist ideology, which sometimes reproduced an opposition to feminism and prevented the advancement of women’s independent activities. At that time, most of the leftist movements in Turkey believed that efforts towards women’s liberation should be abandoned until the realization of class revolution.11

In this context, the PKK rejected the conventional understanding of the Turkish left, which believed that “the question of women should be suspended until the victory of socialism” or “efforts towards women’s liberation should be abandoned until the realization of class revolution.” The organization also rejected the idea that socialism had sufficiently solved women’s problems in the past. In doing so, PKK distinguished itself both from the Turkish left and from Kurdish nationalists. The PKK criticized patriarchy, especially the institution of the family and the honor system in Kurdistan, while accusing Turkish leftists of turning a blind eye to Turkey’s internal colonialism against the Kurds, who made up twenty percent of the country’s population.

November 19, 2022: protesters barricading the Kurdish city of Mahabad.

Since the late 1980s, Kurdish women have worked towards a politics based on women’s self-governance within the PKK, which distinguished them from the dominant currents of feminism in Turkey and from the men within other revolutionary organizations.12 From 1995 on, they carried out an intersectional struggle in which the question of women, the liberation of Kurdistan, and class and ecology became of equal significance. They implied that the time had come to solve the women’s issue during the revolution, not after: we should be able to carry out a social revolution for gender equality along with a political revolution and an armed struggle to build a socialist Kurdistan. In this respect, they were far ahead of their times and urged a progressive politics on the entire party.13

October 1, 2022: protesters set their scarves on fire while marching down a street in Tehran.

The importance of such an intersectional approach becomes clearer when we compare the PKK with its leftist counterparts, especially political organizations that have existed since the 1990s. For instance, in the left movements in Palestine, until recently, the issue of women has always remained on the sidelines. The Tala’at campaign (a Palestinian feminist movement) was launched in 2018, following the so-called “honor” murder of Palestinian women by their families, aiming to address the issue of violence against women along with the issue of Israeli occupation of Palestine. Palestinian women took to the streets under the slogan “There is no free homeland without free women,” a slogan that was chanted three decades ago in the part of Kurdistan ruled by Turkey. However, Palestinian men severely criticized these women, claiming that the main problem right now is Israeli colonialism and “it is not the time” for women to hold street protests. They believed Palestinian women portray a “primitive” image of Palestinian men that provides justifications to the Israeli right-wing, when it is the Israeli state that uses the most brutal violence against the Palestinian people. But these women did not hesitate; they emaphasized that solving women’s issues should not be postponed after liberation from Israeli colonialist forces.14

As Kurdish, Turkish, Baloch, and Arab women in Iran, we have faced similar problems for many years. Fighting against the oppressive central government, as the main enemy that has militarized our place of residence, has always been prioritized. Because state-driven nationalism has put the marginalized regions of the country in a permanent state of emergency, some nationalist Kurdish, Turkish, Arab, and Baloch activists have asked us not to give nationalists and centralists an opportunity to take advantage of women’s protests against violence to misrepresent the men. “Now is not the right time,” they implied. After liberation, we will have enough time to address women’s issues. There are supposedly more urgent problems than those that women face, which can be postponed or completely abandoned.

But it has become clear to women in Iran, as in many other countries, that the fights against both patriarchy and national and class oppression must proceed simultaneously. Otherwise, after the liberation of the nation and the realization of socialist revolutions, women might be sent to their homes or removed from the public space. This was an important lesson that the Kurdish women in Bakur Kurdistan had learned from the history of the socialist struggles before them. They positioned the freedom of women in their political agenda alongside the freedom of Kurdistan and freedom from capitalism. As a result, this movement produced many slogans about women and their importance. They tried to introduce the issue of gender equality into the party agenda while fighting the patriarchal nationalism represented by the repressive exclusionist government and giving a new value to lower-class women.15 They shifted what it meant to be a woman in the collective imagination and forced the traditionally male-dominated Kurdish parties to place more importance on gender.

October 1, 2022: protesters set their scarves on fire while marching down a street in Tehran.

Women not only participated in the movement—they became its pioneers. They were the bearers of free life in a situation where the repression of the Turkish government had turned daily life into a permanent crisis. Accordingly, the slogan “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” implies above all that “The time has come” to achieve a better and freer life today, to address the women’s issues, not to postpone gender oppression by prioritizing class or national oppression.

“Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” is the outcome of the struggles of women who have been fighting on several fronts at the same time. With several decades of consistent resistance, they have brought women from behind the scenes to the political stage of Kurdistan, taken gender equality from an unknown future to the present, and from private space to public discourse. Although this may seem obvious at first glance, it has not been fully accepted in the field of struggle, at least in Iran. Setting aside the right-wing and sexist approach to women in Iran, there are still many on the left who think that addressing gender oppression can create divisions within the working class, that gender oppression is not as important as class oppression. Of course, class and gender do not exist independently of one another, since capitalism reproduces itself via gendered, racial, and ethnic inequalities. For many, though, the intersection between the two is not certain.

The connection of national (ethnic) oppression with gender and class oppression is even more challenging and has created more questions. Non-Persian peoples in Iran have been doubly exploited and colonized for more than a century, living under the domination of a powerful system of repression that does not necessarily act with the same intensity in the “central” regions—as we can see when we look at the bloody Friday in Zahedan and the bloody Saturday in Sanandaj in September and October 2022 and the mass killings in November 2018 in the marginal areas of the country.16

October 29, 2022. The person filming says, “This is Kurdistan, the nightmare of fascists, the nightmare of chauvinists, the nightmare of dictators. Down with despotism, down with colonization and exploitation, down with the dictator, down with fascism, down with opportunism. Long live the revolution, long live equality, long live the oppressed peoples, long live socialism, long live happiness! Beauty is currently in the streets in Iran…”

We cannot imagine a free future without formulating a political understanding of how all kinds of oppressions fit together. As long as activists are not able to address ethnic oppression and the right to self-determination in Iran, they will contribute to minorities’ mistrust of progressives in the urban core. Ironically, most of them are pushed towards “separatism,” which historically has never been the wish of the Kurds, Baloch People, or other minority groups—for they realize that they cannot wait for the approval and recognition of the urban center, they must transform their social lives themselves. This trend could be very challenging for the future of politics in Iran. Ironically, the chief thing giving it force is those who deny the importance of self-determination, not ethnic minorities (as the propaganda of the Islamic Republic and the Iranian right allege). Ethnic minorities have always shown a desire to unite with the urban centers according to legitimate political conditions. During the recent revolutionary uprising, this culminated in the chanting of slogans in defence of unity in the marginal cities of the country, especially in Kurdistan and Baluchistan.

For years, leftists oriented towards “working-class struggles” have denied the importance of feminism and the need to prioritize the question of gender. Kurdish nationalists also tried to spread the myth that patriarchy does not exist in Kurdistan and if there is any violence, it is mostly rooted in the oppression of the colonialist central government. Even recently, during Jina’s uprising, a video was published by some Iranian Kurdish activists in which Kurdish women say in different ways that “The hijab is not a Kurdish woman’s problem”! Meanwhile, every day, there are reports of Kurdish women’s conflicts with their families and the patriarchal structure of society over covering their bodies and control of their sexuality.

The widespread acceptance of the slogan “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” shows the necessity of this form of intersectional politics in today’s Iran; it represents a potential alternative to the Islamic Republic. In direct contrast to the male-dominated and repressive regime, which has denied various groups any rights at all—especially women and queer people, but also labor organizers, ethnic and environmental activists, and other marginalized groups—”Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” offers a unifying alternative embracing plural oppressions. For this very reason, sexist nationalists and reactionaries, often close to monarchists, attempt to replace it with other slogans, including populist and chauvinist slogans such as “Man, Patriot, Prosperity.” Similarly, during the first bloody weeks of the Jina uprising, the military forces in Kurdistan erased the slogan “Woman, life, freedom” from the walls of Kurdish cities, writing “Woman, chastity, honor” or “Man, glory, authority,” which shows how frightened the regime is by the feminist and intersectional character of the revolutionary slogan.

In view of the political implications of the slogan, it seems vital to preserve it at this historical moment in Iran. If any other form of unity does not reflect its pluralism, it could only be a hypocritical and opportunistic strategy to gain homogenizing and eliminationist power in the future of Iran.

Students at Sine’s university in Kurdistan in Iran dancing while chanting “Jin Jiyan Azadi.”

Women and ethnic minorities have walked a long and difficult road to bring this society to the point at which it accepts that gender and ethnic oppression is not just “their problem” but a societal issue that must be addressed for everyone’s sake. Getting rid of class oppression will require simultaneously abolishing other forms of oppression that have made some people “minorities” (not necessarily quantitatively) and “peripheral” (not necessarily geographically). Just as for the women of Turkish Kurdistan, “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” implied that women’s concerns should not be deprioritized, the translation of this slogan into the Iranian context proposes that we should not postpone addressing gender and ethnic oppression or other forms of domination until the Islamic Republic falls. This slogan can help us to prevent reactionaries from appropriating and manipulating our movements.

To increase our sensitivity to the suppression of the voices of marginalized ethnic women, we can use the Kurdish version of the slogan “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” even more than the Persian one, which everyone already understands and repeats. This is a symbolic action, but in these critical moments it can strengthen the unity that we need and provide a basis to consolidate mutual trust.

People have chanted slogans in Farsi many times in non-Persian regions of the country; now, it is time for the central regions to show more openness to non-Persian slogans. Similarly, the self-conscious employment of Jina, the Kurdish name, instead of Mahsa (a Persian name) renders visible the state oppression that has deprived us of our mother tongue in various spheres, including the names we can give our children. This is what the people of non-Persian regions have faced for years. Not only Jina did become the code name for the revolutionary uprising of the Iranian people, but her name became a code for resurrection despite the dominance of an Iranian nationalism that has criminalized non-Persian people to such an extent that even non-Persian names are considered a threat.17

Her family called her “Jina.” They mourned her by that name. Her mother wrote to her in virtual spaces by that name. Her tombstone reads “Jina Amini.” However, Jina is identified by the majority of Persian people as “Mahsa Amini,” and the latter has become a trend. This is no coincidence. The name Jina, like her death, represents the symbolic oppressions that she faced as a non-Persian woman. If we consider one of the tasks of revolutionary movements to highlight and articulate multiple internally related forms of oppression, the “Women, Life, Freedom” movement can achieve unity by recognizing differences now, not later. This is the only way to build a harmonious but inclusive alternative. Those who struggle for freedom, equality, and justice in Iran must fight on several fronts at the same time, unlike the right-wing opposition that has shied away from this responsibility under the false umbrella of “Ettehad” (‘unity’), putting a exclusionary politics on its agenda.

A woman protesting Mahsa Amini’s murder in Tehran, Iran, on October 7, 2022.

-

Abdullah Öcalan, War and Peace in Kurdistan (International Initiative, 2012 [2008]). ↩

-

Somayeh Rostampour, “Gender, local knowledge and revolutionary militancy. Political and armed mobilizations of Kurdish women in the PKK after 1978,” PhD thesis, September 2022, University of Paris 8, France. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Abdullah Öcalan, Prison Writings: The Roots of Civilisation (Transmedia Publishing, 2007). ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Saadi Sardar, “A Feminist Revolution is Challenging Iran’s Regime, Kurdish Peace Institute,” September 26, 2022 (accessed October 2022) ↩

-

For example, when Turkey joined the European Union around 2000 on the condition of granting certain political rights to “ethnic minorities,” women seized the opportunity, while the PKK began to pursue its aims through means other than armed struggle, including participation in parliamentary elections and spreading its political influence in civil movements such as councils. ↩

-

One of the three women who were assassinated in Paris was Sakine Cansız, one of the founders of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, the most important female figure in the history of PKK. She spent more than eight years in Turkish prisons, where her breasts were cut off under torture. Read this for more information about Sakineh Jansez. ↩

-

For example, “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” was the chief slogan in the battle that women from Rojava fought against the Islamic State in Afrin (a canton of Rojava, which is now occupied by the Turkish state) from December 2017 to March 2018. From 2018 to 2021, 83 women were killed, 200 women were kidnapped, and 70 women were raped in Afrin under the military occupation of the expansionist Turkish government. ↩

-

For the same reason, after the Jina uprising began, the government agency Fars news published a text on its website on October 7, 2022 entitled: “40 years ago, Komle sang ‘woman, life, freedom,’ but in a different way.” ↩

-

For some well-known socialist organizations such as the MLKP (Marxist–Leninist Communist Party), the discussions about women’s struggles began in the mid-2000s. Many other organizations (e.g., DHKP-C or TIKB) believed that they did not have a problem with sexism and therefore had no need to reflect on it. ↩

-

Despite the tendency of the PKK to raise the issue of gender equality, until nearly 1995, this party still had a male-dominated structure; its leader was an influential man, and gender inequality was reproduced in various forms within the party itself. The women in this party, after gaining experience and increasing their number since the early 1990s, concluded that their struggle could not be focused only on the liberation of Kurdistan, because even if Kurdistan were liberated, they would remain under domination of the men. Consequently, they joined forces in order to establish women-only organizations in which they could strengthen themselves and make decisions independently to advance women’s self-governance alongside the self-governance of Kurdistan. ↩

-

If today, the PKK is known for the importance that it has given to gender issues, that is due to the continuous activities of the women of the party, which started from the guerrillas in Shakh (the Qandil mountains) and followed in Shar (cities) by feminist and queer supporters with a different approach. ↩

-

This campaign was a big step forward. It continued for eight months, becoming the basis for a wave of protests in Arab countries in 2019. The participants even issued a cross-border call to Palestinian women in camps in Lebanon and other countries, asking them to join the campaign. Consequently, for the first time, in 2018, we witnessed demonstrations by women in these camps, and non-Palestinian immigrant women joined them in some countries. Immigrant women living in Western countries who joined the campaign had similar conflicting feelings: they feared that if they spoke about domestic violence publicly and collectively, they would be giving an excuse to the anti-immigrant right wing in the West. ↩

-

Although the PKK has theoretically distanced itself from Maoism, it has always given a lot of space to “ordinary” women in practice, especially women from the lower classes. For example, the mayor of Mardin (Sürgücü) in Turkish Kurdistan, who was supported and elected by a pro-PKK party, was a forty-year-old woman who had eight children and very little education. By maintaining constant contact with women and with different classes, the PKK was able to turn what was hitherto considered “exceptional” into a common model in Kurdistan. ↩

-

Rostampour, Somayeh. “Ethnic Cleavages in the Iranian Protest Movement.” Multitudes 83, no. 2 (2021): 112-119. ↩

-

Although it is still not clear why Jina (Mahsa) Amini herself had two names, in general, many people in Kurdistan have two names—one in Farsi to be used in their birth certificate and a second one in Kurdish to be called in their community. This is because some registrars refuse to register Kurdish names, on the grounds that “this name is not Iranian”; in other cases, families prefer Farsi names on birth certificates, so that their children will not be discriminated against or humiliated because of their Kurdish identity. ↩