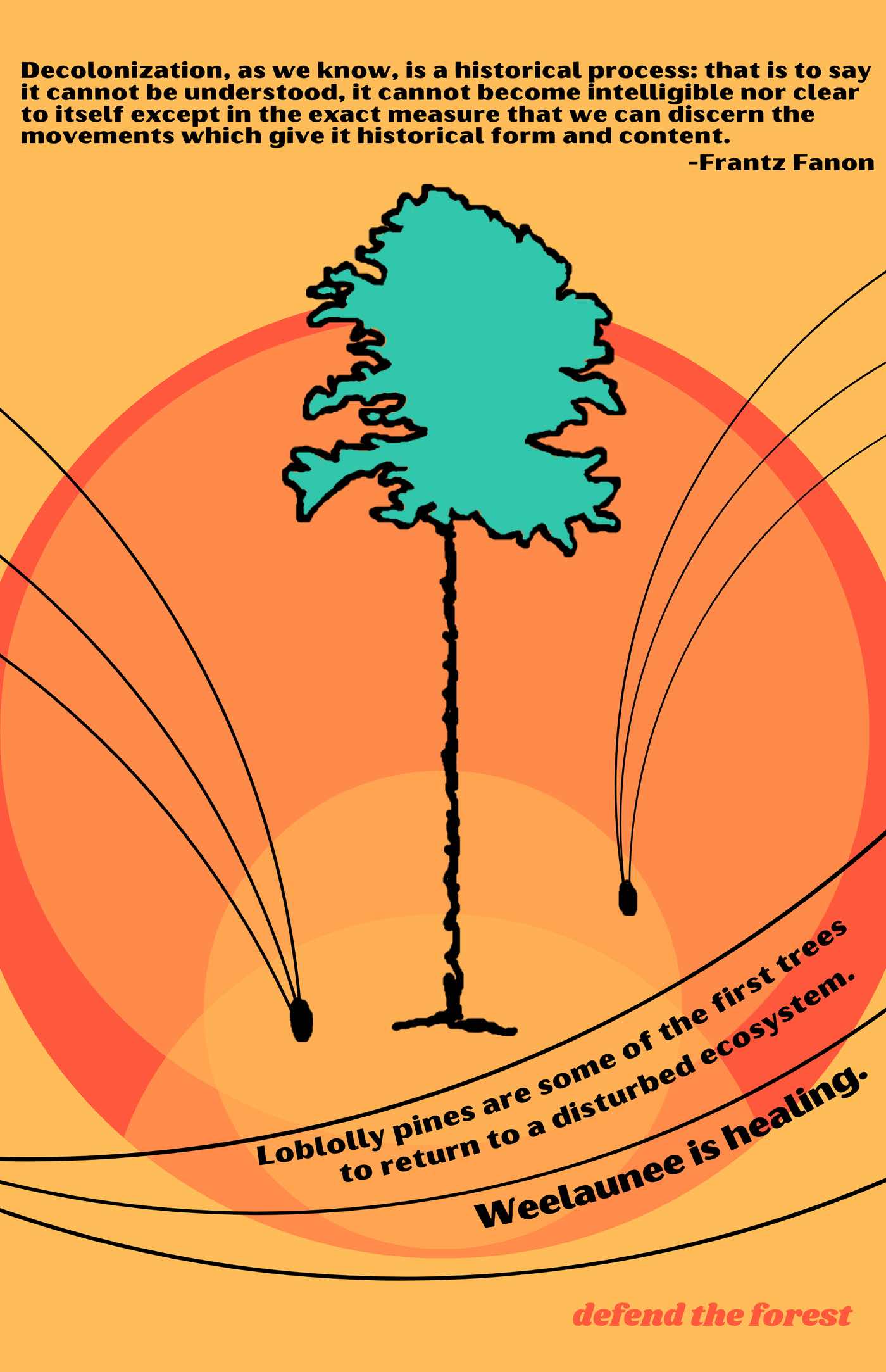

In the following text, participants in the movement to defend Weelaunee Forest in Atlanta, Georgia describe some of the values that animate this struggle. For background on the movement, start here.

This is a collection of short essays reflecting on the abundance that exists in our communities and in the more-than-human world, and how we not only can practice gratitude for this abundance but embody it as a way of approaching the world.

We dedicate this work to our friend, Tortuguita, who was part of these conversations. Georgia State Troopers killed Tortuguita on January 18, 2023 at the forest they loved so dearly. This piece is for them and for all past, present, and future Warriors defending and loving the Sacred Web of Abundance everywhere.

With profound love and admiration,

The Weelaunee Web Collective: Abundia, Jesse, Jordan, & Mara

Introduction

The threads of our lives have been slowly woven together through meals cooked communally, organizing meetings, bonfires and late conversations, foraging, harvesting, taking care of each other, and, lately, mourning a fallen comrade and friend. We all came together to protect Weelaunee Forest: the trees, waters, people, and all beings of this land. We came together to Stop Cop City and the violent military occupation of police in our communities, especially the Black and Brown ones, in Atlanta, Georgia. We came together amid COVID, when we felt the loss of closeness with our people, knowing we had to find creative ways of fostering community. We have come together to build the world we want to live in, even as we recognize we are all swimming in the extractive and oppressive systems of colonization, white supremacy, and capitalism, programmed for convenience and quick rewards. We keep coming back together, gathering with each other, to live in the joy and rest and wellness of community care.

The topic of this piece is the Sacred Web of Abundance (SWoA). The larger Sacred Web of Abundance is the sum of the vast, intricate system that sustains all life on this planet. Your Sacred Web of Abundance is the place that you live, the ways in which it sustains you, and the ways in which you sustain it. We are here to be part of this web and invite in others who are on the same land. What we have found is that the Sacred Web of Abundance, with her billions of years of wisdom, is there for us, waiting for our gratitude, delight, offerings, rituals, and ceremonies—waiting to build a relationship with us.

These unique ways of considering abundance emanate from a particular place, the South River Forest, known as the Weelaunee Forest on old maps of Georgia. These ideas come from conversations among a group of people as they adapt to living in that place.

Often overlooked, we feel that the Sacred Web of Abundance is a powerful idea for radical organizing. It is here for us as a force for liberation—as it has existed since time immemorial—and to help us fix the mess we are in by reclaiming our community power and centering it around the land that the community inhabits. In these times, we are all called to create new forms of organizing and direct action; new language, perspectives, and modes of being; and infrastructure for healing, care, and safety that centers the SWoA as key praxis for autonomous communities to build on.

Abundance points to the interconnected reliance on both self and community to provide for all; therefore, re-creating and reconnecting to our Sacred Web of Abundance are both essential collective actions for a new political project aimed at freedom and autonomy. Abundance is here, already, alive around us, if we open ourselves to its presence. We do not take this reliance on abundance for granted, as we did with the gift of human contact and proximity pre-COVID. Instead, we want to nourish and be nourished in its care, find inspiration from it to build new mutual aid infrastructure, gather strength to defend it from extractivism and capitalism everywhere, and create new cultures and ways of being and relating to each other and all the members of the SWoA.

The Sacred Web of Abundance

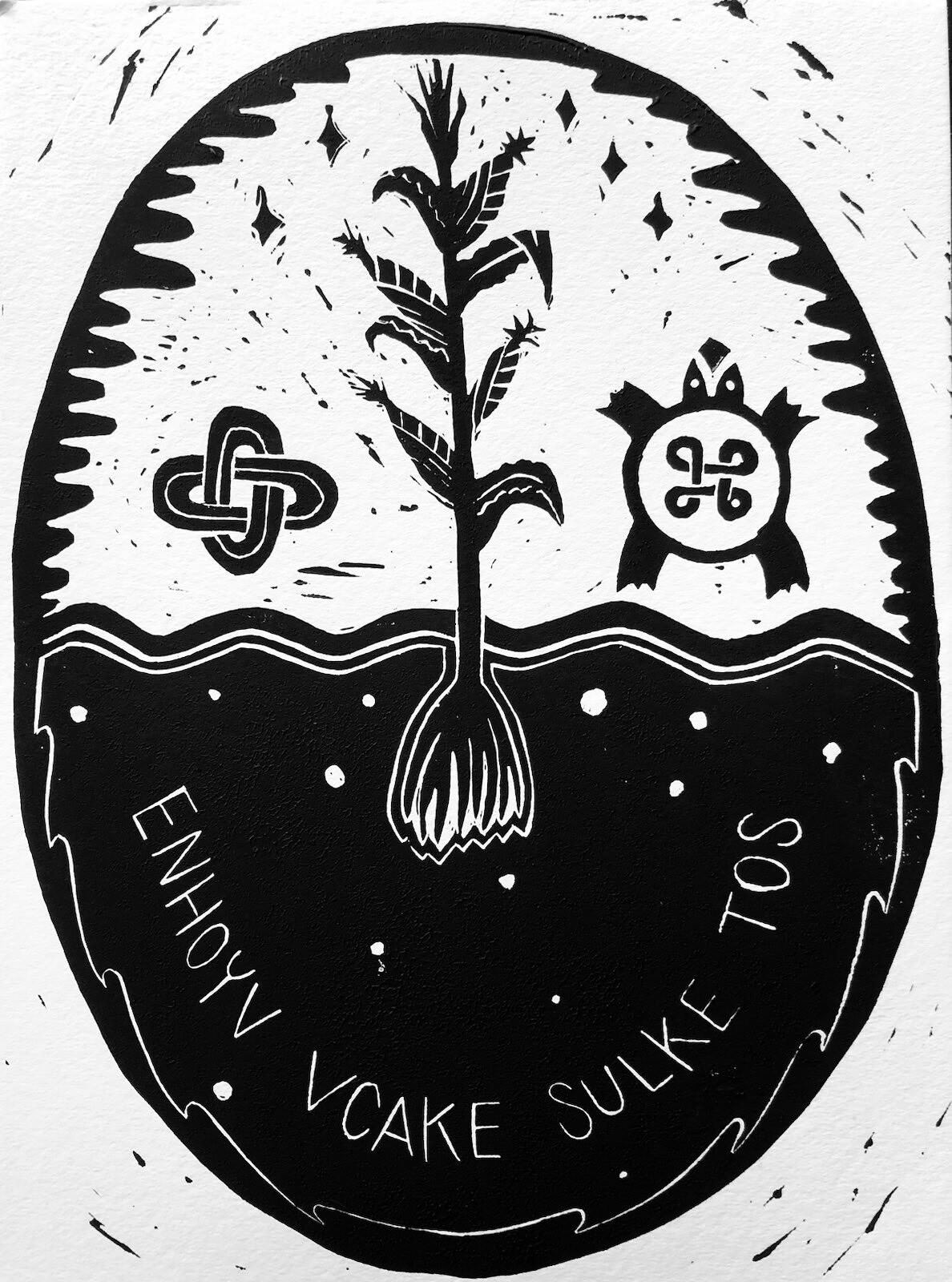

The Mvskoke’s main religious ceremony is Pvsketv (Green Corn), a millennia-old multi-ritual revolving around the harvest of new corn at the height of summer. Pvsketv aims at the renewal and balancing of relationships between humans, land, animals, spaces that humans inhabit, and spirit. In conversations with Mvskoke language scholars, I was told that to them, the concept of abundance as a single word does not exist. Reverend Rosemary McCombs Maxey, a Muscogee Creek citizen of Oklahoma and Mvskoke language educator, shared in her class the phrase enhoyv vcake sulke tos, which translates as “webs that are precious are many.” This resonates deeply with us and our experience of the Sacred Web of Abundance.

We understand the Sacred Web of Abundance as a living entity with intricate and ever-changing processes and systems. These webs have been woven collectively and continuously for more than 4.5 billion years by all that are part of it, from flora and fauna to fungi, elements, and humans. In the case of the Atlanta SWoA, the weaving of human species was done first by the Mvskoke people.

The Sacred Web of Abundance is always in flux, renewing and healing itself through what we call regional ecosystems, or microclimates, and it’s always nurturing the species connected to it through a series of processes that contain limitless knowledge. From the SWoA, we can take all of our cues to reimagine the future and make everything anew, in each community and even the world. We can reflect or mimic the SWoA when creating new mutual aid infrastructure, culture, accessibility, meaning, and much more. But first, we must reconnect with it both personally and collectively in a deeper way.

Each Sacred Web of Abundance is unique and distinct, yet interconnected. We feel that SWoA is not an abstract concept like “nature/environment/ecosystem” but rather a concrete one. You can learn about its history and the particular ways the land you are on likes to be cared for, celebrated, and loved; you can touch, feel, see, get closer to, interact with, learn from, feed and sustain yourself and your community by, and build meaning and life around, a particular SWoA. Furthermore, the concept of the SWoA is easy to relate to, given that we are all already in a relationship with it to some degree. Every human in every culture has a personal experience of abundance as a physical phenomenon, as well as of the SWoA as a network in nature, yet people are often not entirely aware of it. Under capitalism, we exist in a permanent mode of scarcity and extraction, whether we are conscious of it or not. This mode is interrupted and challenged when, collectively, we start weaving back into the SWoA.

In our early history, the human experience was centered around the Sacred Web of Abundance. We built everything from our relationship with it, including meaning, ritual, ceremony, agriculture, art, economies, sustenance, and culture. In more recent history, we have been slowly but surely estranged from the SWoA as we’ve developed culture around hierarchical power structures, normalizing extractivist systems and accumulation. Until the end of the last century, especially prior to the Industrial Revolution, many people were still foraging, growing, processing, celebrating, and sharing food collectively while still worshiping their particular SWoA. There are still people doing this today, but they are in the minority now, frequently self-segregated or pushed to live in isolation under attack from a global market economy.

Regardless of how radical our political ideas might be, most people’s relationship with their Sacred Web of Abundance is strained or truncated by the permanent mediation of capitalism and its narrowness. Capitalism controls our daily experience of the SWoA because people have to prioritize survival and because we’ve been conditioned to live with convenience and instant gratification. That’s why we don’t know, or have forgotten, how to accept the gifts of our particular SWoA. That’s why we are likely to step on an acorn or walk past the seasonal gifts of abundance on our way to work or to buy food at the grocery store, always distracted by the transactional. That’s why, in radical activist circles, we don’t prioritize foraging, growing, processing, distributing, sharing, or celebrating foods, which have been the main collective means of connecting and autonomous organizing throughout history.

Today, there is not just a misinformation crisis but also a crisis of motivation. Especially among young people, there is a lack of concrete ideologies that one can identify closely with, directly benefit from, experience, and be empowered to act on. We see this with the climate emergency and other pressing issues. In the face of the greatest crisis in modern history, organizers often recycle strategies for organizing that either no longer work or do not appear relevant to enough people to make use of the human energy that the climate emergency deserves, rendering this organizing performative rather than constructive. Sadly, even with the climate crisis at the forefront, the consistent trend within all of our organizing is the absence of consideration or even awareness of the Sacred Web of Abundance as a political idea, radical praxis, way of being, and urgent priority to attend to—that is, as an entity to defend.

Furthermore, most settler-imposed economic, political, spiritual, religious, and philosophical systems (communism, capitalism, socialism, etc.) have ignored the Sacred Web of Abundance as a critical collective experience and radical idea. Anarchism, too, has largely ignored it, and so sadly passed up the opportunity to effectively challenge and destabilize capitalism and private property. It’s uncomfortable for Western systems of thinking to build around the expansiveness of the SWoA, so instead they’ve focused on the extremely limited experience of humans, and a limited selection of humans at that. Therefore, all of the systems we live under or aspire to live under are weak, without self-actualization or resilience, because they all ignore the most powerful and common experience on this planet for all species: our interconnectivity to the SWoA, and our common histories of weaving and living in abundance.

Weaving Collectively Back to Our Beloved Sacred Web of Abundance in Atlanta

Since we started to organize against the construction of Cop City in Weelaunee Forest almost two years ago, we’ve been having deep conversations about collectively weaving ourselves back into the Sacred Web of Abundance. While bringing food and water to visit friends and comrades, before events and after walk-throughs, or during morning coffee at the open kitchen, we’ve become committed to testing out our ideas, not just talking about them. This commitment can be seen in the three Atlanta experiences shared below.

Pecan Foraging Morning

This past autumn, in 2022, Jordan and I went to Kirkwood, a residential neighborhood in Atlanta, searching for pecans. Jordan knew of a house where the most beautiful pecans could be found outside, and sure enough, we arrived to a blanket of them. They were big and soft, with thin and easy-to-crack shells, full of milky, earthy flavors and a strong dirt fragrance. We knocked on the house’s door, and when a woman answered, we asked if we could share in her abundance. “Go ahead, they are just going to go bad!” she said, so we got down on the soil until we had many bags full. After some time, the woman came back out with lemonade and some questions for us. The conversation went something like this:

“Why are you doing that?” she inquired.

“Because we love pecans! And we appreciate the gifts of the earth. We want to be connected to this pecan tree and web of abundance.”

“Oh, that’s so true! I’ve never thought about it like that.”

She started sharing stories of her family growing up in California, how they would go hiking and she would collect little things. She told us we reminded her of her own childhood practice of foraging and feeling that connection.

“Are you from here?” she asked. “Do you do this a lot?”

“Yes! We’re part of a new collective, Common Abundance,1 and we want to make foraging accessible to all people.”

“What do you do with the things you forage?”

“Well, we process and share and enjoy them; that’s the whole point of foraging! We’re going to make acorn pancakes next Saturday from our foraging too.”

We continued picking up the pecans, and she began to reflect on the tree and how blessed she is to have this particular tree in front of her home. Though she doesn’t provide it with active care, it supplies such gloriously big pecans and is strong and healthy.

We thanked her—after filling up seven bags! We never take everything, of course, for the pecans left behind will nourish other beings and soils. Who knows who will come around next, or where those pecans will land again, or whether they’ll sprout into a new tree or die and offer their life back to the earth.

As we were about to leave, she said, “Come forage anytime, no need to ask! I’ll tell my husband and son that people are welcome to forage here. I want to support this collective.” She gave us her contact information and offered her skills in storytelling and tech. Before we left, she added, “I recognize this is not my land, even though I bought it a year ago. I’m not a steward here. I haven’t been taking care of these trees. Indigenous people were stewards here once, and probably Black people stewarded this land before me. That’s probably why these pecans are so beautiful. These pecans aren’t even mine. Come whenever you want. You are welcome anytime!”

We were amazed. Much to our surprise, we didn’t have to lecture to her, bring her to a documentary viewing night, or make her read Marx! We were just living the ethics of abundance, honoring the gifts of the land, and listening to the stories that emerged from the tree and this woman. The physical embodiment of abundance was so attractive to her, so welcoming, that she brought her whole self to it and broke open her own ideas of private property. She got it.

Foraging a Connection

My friend Jesse and I stand in front of a small crater that cups a mangle of severed roots. We are gathered to mourn and defy. Over the past two days, Weelaunee People’s Park has been illegally bulldozed by a private developer who was tired of not getting his way. In his tantrum, his workers have torn up what was planted with care. At least six serviceberry trees were felled. They are stacked in a sad pile on the southern edge of the park.

Have you ever tasted a fresh serviceberry? In her essay dedicated to the fruit, “The Serviceberry: An Economy of Abundance,” Robin Wall Kimmerer invites us to imagine “a fruit that tastes like a Blueberry crossed with the satisfying heft of an Apple, a touch of rosewater and a minuscule crunch of almond-flavored seeds.”2 This understory tree lines parks, streets, forests, and forest edges from the southeast of the so-called United States to the northeast of so-called Canada.

I first met and tasted serviceberries through the Concrete Jungle food map. The map lists the public fruit trees in Atlanta—pears, apples, plums, and more. Concrete Jungle uses this map to organize volunteers to gather fresh produce and deliver that food to pantries and shelters throughout the city. But for these volunteers and other map users, myself included, it presents an exciting new geography of abundance. A portal opens into a world where every lawn, side street, forest, and forest edge becomes a possible source of food, new and wild flavors, and opportunities for learning, curiosity, sharing, and connection.

After many seasons of picking spring berries with friends, shaking apples and persimmons onto tarps into the fall and early winter, and expanding from fruits and nuts to wild greens, roots, and fungi, I’ve formed my own mental map of the abundant gifts hiding in plain sight. I’m not much of a visual artist, but even if I were, I’m not sure that I could paint this map for you. It is magical and dynamic. It re-renders as the seasons shift. It reroutes me toward the pecan tree with the fattest nuts on my bike ride home. It surfaces map pins of memories that dance larger as I approach.

There is the temptation to translate this newfound abundance into a dollar amount, especially given farmers’ market novelties like pecans at $5 a pound or chanterelles at $15. But when we come to something like acorn flour, which can be purchased at an Asian supermarket for a few dollars, the market economy comes out far ahead. Once you account for the hours gathering, drying, shelling, leeching, dehydrating, grinding, and storing, you’re looking at an hourly equivalent earning far below any minimum wage.

This is where the concept of the Sacred Web of Abundance becomes a useful tool. A monetary calculation doesn’t account for the refreshing richness of time spent outside under the trees, with the scent of earth and the soothingly repetitive task of sorting through eligible nuts. (This one has a crack in it, this one a weevil hole, this one is too small to be worth the effort.) It doesn’t account for the time spent with friends that makes the task more enriching. It doesn’t factor in the satisfaction of gathering to feast on acorn pancakes covered with blackberry jam. It does not account for the increased connection and feeling of responsibility toward our kin.

The average supermarket (if you can afford it) is abundant, true, but at its core, it’s extractive. It is not woven into the Sacred Web of Abundance. Commodities—items broken down into individual, indistinguishable units—are, by definition, disconnected. The cost of this disconnection is immeasurable; it is at the center of our culture of death and suffering.

Weaving an appreciation for abundance is the task of culture and relationship building. This is the goal of our new collective, Common Abundance. Through the sharing of tools and knowledge around foraging, specifically nuts and other nutrient-dense, high-calorie foods, we hope to make it easier and more accessible to connect to the web. Together, we can increase regional food autonomy by lowering barriers to harvesting uncultivated foods. As the taste for foraging grows, so must the amount of forageable land. This appetite can be fed through acts of ecosystem reciprocity, repair, and land defense.

This past autumn, in 2022, Common Abundance gathered in a park for an acorn skill share. We were able to demonstrate the many steps it takes to turn acorns into food for humans. Fear melted away as we collaborated on this multistep process and enthusiasm took its place. The participants were able to taste acorn pancakes fresh off the griddle, topped with jams and jellies also made with local forageables.

Our nutcrackers were present for display and use—from Grandpa’s Goodie Getter for cracking the rock-hard shells of the black walnut to the Kinetic Pecan Cracker, an electric tool for speeding up the shelling of pecans. It’s our goal to one day have a facility where community members can bring their foraged bounty to process with ease.

The steps we’ve made in this direction give me hope. While we mourn the loss of our serviceberry friends at the hands of a cruel, disconnected private developer, I have no doubt that they will be replanted. Too many people have tasted their berries and embarked upon a loving, reciprocal relationship with both the fruit and the tree.

So today, back at Weelaunee People’s Park, we follow the example of the spider, who doesn’t throw up eight limbs and swear off weaving when some deer or human unwittingly plows through its web. We set about cleaning up the park and preparing for that evening’s potluck in the ruins. Lights glow above folding tables. We share stories, songs, and reassurances. We feel full and connected. We eat.

Planting the Seeds of Abundance: Dandelion Fest

Some of the seeds of the Sacred Web of Abundance were planted during the Dandelion Fest, the money-less market and festival put on annually by Mariposas Rebeldes.3 There are few public spaces in the United States, especially queer ones, where spending money is not socially expected—or even compulsory. We are always encouraged to be consumers, buying things we don’t need and seeking to meet our individual needs instead of collective ones. The Dandelion Fest aimed to show people what it felt like to be in a queer space where there wasn’t an expectation to spend money, and where money wasn’t a barrier to accessing community. The festival was not permanent but ephemeral; an experimental experience of a horizontal society full of things that we could gift each other or trade with each other—one without scarcity. But what if we already lived in such a society?

Capitalism has brainwashed us into believing in the myth of scarcity. But we already live in abundance. The Dandelion Fest demonstrated this. Dozens of people came together to share food, medicine, plants, and clothes, plus their talents on the open mic. It felt like many other queer outdoor markets in Atlanta—except you didn’t leave spending $50. Soon, people were asking us when we were going to put on the next festival—it had become a staple of Atlanta’s DIY scene.

Dandelion fest challenged our dominant consumerist culture, which has infiltrated even the most leftist spaces. It asked the question: if we could pull something like this off, can we do it at a larger scale? Why aren’t we already living like this? Obviously, there are many practical answers to this question, living in a capitalist society, not having the infrastructure for robust mutual aid networks, and most of our modern education systems prioritizing the remembrance of facts over knowledge that would be relevant to our survival. We’re not saying we’re creating that infrastructure by throwing a free festival, but by doing this we hope to, even in small pockets, start shifting attitudes and culture around spending money and showing up for each other.

We also can’t say that we conceived of the philosophy of horizontal trade ourselves, which was the intention that the festival was centered around. We have been heavily inspired by the project El Cambalache, a mutual aid project and “free store” run by a group of primarily Indigenous women in Chiapas, Mexico. The philosophy of Cambalache, meaning literally “to swap” in Spanish, aims to remove the hierarchy of transactional value, allowing people to give what they don’t need and ask for what they do. This theory asks to unpack why certain things in our society have more value than others. Cambalache also forces people to be in relationship to each other, which buying and gifting doesn’t always necessitate. Cambalache also does not subscribe to the notion of charity, being that charity requires a hierarchy in which a person with resources or money gives to someone who lacks these things. Charity is diametrically opposed to horizontal exchange.

After the Dandelion Fest, we were left with feelings of wanting something more permanent. We saw how much could happen when people came together, even for a single afternoon, and brought with them the abundance that existed in their communities. But why couldn’t people help each other meet their needs on a daily basis? We knew we weren’t going to abolish capitalism overnight, so we settled for a Facebook page and a group chat. Our wish was that the seeds we planted during the festival would grow into a web of community, resources, mutual aid, and abundance! These virtual spaces would be a resource people could visit before or instead of going to the store and spending money on something new.

So far, the Cambalache chat has been beautiful to see: a place where people ask for care of their dogs, help building chicken coops, or a hand in fixing their cars. A place where people give away everything from shoes that no longer fit them to medicine and makeup. It’s a small chat, but we already see people getting their needs met! We hope that by encouraging people to interrogate and reorient their relationship to consuming and buying, that not only will we save people a few bucks, but also foster a sense of community. Hopefully they will start talking to their neighbors when they run out of eggs, instead of going to the Kroger self-checkout.

Radical Stewardship

In our view, the concept of radical stewardship stems from the recognition of the millennia of knowledge and work of the Indigenous people of any given land, the land’s first stewards. Radical stewardship is in alignment with the rights and interests of the first stewards of the land, whether they choose to demand the land back, move to “rematriate” it, or exercise their right to keep taking care of it. In our case here in Atlanta, these first stewards are the Mvskoke people.

Radical stewardship’s tenets are starting to reemerge due to our collective desire to reconnect with our beloved Sacred Web of Abundance. Right now, our work is to ask Mvskoke people, and Indigenous people everywhere, to help us give solid meaning to how radical stewardship works today. Should they be open to sharing with us what radical stewardship means to them and what practices are more beneficial to the land, we can continue to ground our lives, spirituality, and organizing in this way of being. Still, some of the key tenants are intuitive, like radical stewardship’s collective and dynamic nature (which is necessary for adapting to the challenges of the climate crisis).

Radical stewardship is fundamentally a spiritual way of being. When we allow ourselves to fall deeper into the Sacred Web of Abundance around us, we see how each moment of connection with the earth is a ceremony: we harvest pecans and sing the glory of the pecan tree, we bury the dead bird on the side of the road and mourn a life taken too soon, we speak with the chanterelles growing along the river and ask how we might be nourished by their bodies, we see the cycles of life and death happen again and again around us in seasons and know that we too must live now and will someday die, our body weaving itself back to SWoA—but while we breathe into this world, each connection weaves us tighter into the interconnected world, into abundance.

In his essay “All Land Back, All States Smashed: Free the Earth by Any Means Necessary,” Dan Fischer does the important work of reaching out and asking Native American people what the slogan “Land Back” means to them. This is what Madolyn Rose Wesaw, a Pokagon Band Potawatomi and American Indian Movement organizer, had to say: “I think in general what most [Indigenous] people understand Land Back to mean is returning stewardship of the land to Indigenous hands, because we believe it’s our purpose and we know how to take care of this land… We all agree on returning stewardship and responsibility of this land into Indigenous hands and then also providing us the resources we need to do our jobs, since so much has been taken from our communities.”

As we’re just starting to develop the concept of radical stewardship, and as we shape this idea into our main tool for personal and collective reconnection to the Sacred Web of Abundance, we must continue the paramount work of reaching out and being in constant conversation with Native American and Indigenous people everywhere. By doing this, we ensure that radical stewardship at any particular SWoA in the world is informed by the millennia of knowledge and work of the first stewards of the land.

Weaving Collectively Back to the Sacred Web of Abundance Everywhere

We are just beginning our collective weaving back to our beloved Sacred Web of Abundance thru rituals and ceremonies of praise, reconnection, celebration, learning, and enjoyment, along with the work of creating mutual aid infrastructure that replicates, protects, and enhances our natural SWoA, as well as our organizing rooted in radical stewardship. We feel these ideas acting as spores, landing in ready substrates, feasting on the ways of being that are dead and no longer serve. We feel our interweaving connecting us deeper to the sounds of cicadas while our bodies reflect the light of the summer sun.

Today, the call to reconnect with our Sacred Web of Abundance is stronger and more urgent than ever, given the threats of extractivism, ongoing colonialism and capitalism, and the climate crisis that endangers every SWoA on this planet. Wherever you are, we invite you to join us in weaving back to the SWoA together, celebrating her gifts while learning from and recognizing the work, knowledge, and right to steward the land from the first stewards of the SWoA—Indigenous people everywhere, and the Mvskoke people in Georgia and Atlanta. With this work, our collective SWoA is happy, keeps thriving and providing, and enables us to thrive too in these times that are at once challenging and full of possibilities.

It is our hope that communities will take any or all of these four ideas—abundance, the Sacred Web of Abundance, weaving back into that web, and radical stewardship—and expand, adapt, and shape them to their particular reality and autonomous work. May our weaving back into our beloved SWoA teach us to appreciate the next Pvsketv and sing loud the abundance of corn harvest like the cicadas in the height of new harvest time and bear good fruit in us all, and in all of our communities!

Enhoyv vcake sulke tos. “Webs that are precious are many.”

-

Common Abundance is a collective in Atlanta, Georgia working to make foraging more accessible by sharing knowledge and tools. You can find them on Instagram here. ↩

-

This essay and the larger project that it is attached to are indebted to the writing and thinking of Kimmerer, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. You can find the full essay here. ↩

-

Mariposas Rebeldes is a Latine queer, trans, two-spirit, gender-non-conforming, intersex, lesbian, gay, and bisexual agriculturalist collective building permanence in so-called Atlanta. You can find them on Instagram here. ↩