As everyone knows, we have been suspended from Twitter at the same time that Elon Musk is welcoming notorious neo-Nazis back to the platform. On a platform like Twitter, a project like ours is like a canary in a coal mine: when things change, we are the first to go, and that means the clock is ticking for everyone.

Today, we speak to you from the other side of the great divide. Banned on Facebook, Instagram, and now Twitter, we nonetheless exist and organize. If you can still hear us—if you are reading these words—then there is life after social media. That goes for entire social movements as well as individuals and publishers.

Looking at this situation in a broader historical context, Twitter itself is like a canary in a coal mine. Elon Musk’s acquisition of the platform confirms the end of social media as we have known it, at least for the purposes of positive social change. All the major platforms that played roles in the movements of the past decade have been brought under the direct control of reactionaries determined to make sure that they cannot be used to coordinate resistance.

The question is what comes next. Will reactionary billionaires determine what we can do and think and dream? Or will we establish other channels via which to communicate, other forms of connection, other means of coordination?

Twitter is just the proverbial canary in the coal mine.

Hostile Takeover

When Donald Trump was booted off of Twitter after January 6, it became inevitable that someone from his faction of the ruling class would seek to take over the company.1 Twitter became a symbol of everything that remained beyond their control.

Relative to the size of its user base and its ability to turn a profit, Twitter has been disproportionately influential. This is precisely because it has been moderated differently from Facebook and other such platforms, which have consistently suppressed dissident voices while offering echo chambers for the far right. Twitter has been difficult to monetize, but—perhaps for precisely that reason—it has retained a certain credibility.

Unfortunately, all this made it irresistible to Elon Musk. And thanks to the capitalist market, a billionaire can waltz in and purchase just about anything.

This is especially true today, as wealth inequalities reach new extremes.2 In 2003, Bill Gates was considered the world’s wealthiest man with roughly $40 billion to his name; in January 2022, Elon Musk was valued at over $300 billion. Not long ago, if rich people wanted to take over a major corporation, they had to form a corporation to buy it; today, a single power-crazy billionaire can do it alone.

Now that most of the world’s financial capital has accumulated in a few hands, we are also forced to compete for attention as a new currency so that the capitalist market can go on expanding. This is not just a metaphor: cryptocurrency, for example, derives its entire worth from the fact that people perceive it to possess financial value. It has never been so obvious that the supposedly essential truths on which capitalism is based are simply arbitrary social constructs.

This explains why, having accumulated the most financial capital in the world, Elon Musk set out to gain control of one of the platforms on which attention is distributed.

We should not trust Musk to disclose his true intentions any more than we take Donald Trump at his word. Musk spoke about securing Twitter for “free speech”; by now, it is clear that he meant the opposite. Musk’s acquisition of Twitter lines up with his desire to be the tastemaker-in-chief and to suppress the voices of those critical of himself and other capitalists. The impact of his acquisition of the platform will likely hit hardest in parts of the Global South where Musk is trying to get a foothold for his various business interests at the same time that authoritarian governments are cracking down on social media in order to secure their rule.

When Musk purchased Twitter, it had approximately 7500 employees. He fired half the workforce, prompting many other employees to resign. By Thursday, November 17, less than 3000 remained—a disproportionate number of them dependent on their work visas for their residency of the United States, and therefore at the mercy of Musk’s agenda. In retrospect, this probably was not a question of bad management on Musk’s part, nor a deliberate effort to destroy Twitter itself, but rather a strategy to oust everyone who was not supportive of Musk’s program.

This wave of downsizing created a considerable buzz on the platform, with alarmists suggesting that without those employees, the platform would quickly collapse or suffer a severe security breach. As often occurs, however, the real danger was not that Twitter would come to an end, but that business would continue as usual.

Users crowed about how Musk had declared that “comedy is now legal on Twitter,” then threatened parody accounts with permanent suspension; others went on the offensive with fake accounts, ruining Musk’s initial attempt to roll out $8 credentials and temporarily undermining market confidence in certain profiteering corporations. We saw straitlaced New York Times columnists urging people to follow them on Mastodon as if they were reclusive German hackers. For a moment, it appeared that Musk had unwittingly cast himself in a real-life morality play about the risks of absolute power.

Yet we are not witnessing the demise of a specific platform so much as the end of an era. Once Elon Musk bought it, Twitter collapsing was the best case scenario. Instead, we are in the midst of a boiling frog situation, in which every day, things get a little worse on the platform, but not quite bad enough for most people to quit. Bit by bit, Twitter users are becoming inured to algorithms that promote racist and anti-Semitic material, to the suspension of anti-fascists, to the appearance of neo-Nazis in the center of public discourse.

No conspiracy theories are necessary here. Musk did not to set out to destroy Twitter at the cost of $44 billion dollars and his own reputation as a good manager. He simply wants to control the platform and believes that in the long term, doing so could pay dividends in a currency more valuable than mere money. Since taking charge of Twitter, Musk has sought to employ the same tactics by which he bullied workers into giving him an edge in the aerospace and electric car industries.3 On a platform like Twitter, however, the user base itself is effectively both product and producer—so it is the users as well as the employees who are the target of his tactics.

If Musk’s takeover of Twitter works out and the platform survives, the whole fiasco will set a precedent for similar behavior from other billionaires. In any case, the damage is already done. The old Twitter workforce and culture—not radical by any measure, but arguably less reactionary than the equivalents at comparable social media platforms—is gone. And without the previous Twitter administration as a competitor, other social media corporations will have no incentive to include the voices of those already suppressed on Facebook.

If the New York Times columnists stay on Twitter rather than migrating to Mastodon, they will effectively grant a far-right billionaire the role of moderator in every discussion. But what is happening is not the result of the whim of a single malevolent individual. Relying on market-based means of communication made it inevitable that sooner or later, the ruling class would get to determine who can speak and how.

Let’s go back to the metaphor of the canary in the coal mine. When the canary dies, it’s time to get out of the mine. Now, we’re not necessarily urging you to quit Twitter; it would be better to get permanently suspended for raising a fuss. The point is that it’s not good to have to be in a coal mine in the first place. Even if it doesn’t kill you outright, it diminishes your quality of life. Corporate social media and the social relations it fosters cut us off from other ways of understanding and experiencing the world—and if we maintain the coal mine metaphor, the target of extraction is our sociality itself.

The networks offered by Facebook aren’t new; what’s new is that they seem external to us. We’ve always had social networks, but no one could use them to sell advertisements—nor were they so easy to map. Now they reappear as something we have to consult. People corresponded with old friends, taught themselves skills, and heard about public events long before email, Google, and Twitter. Of course, these technologies are extremely helpful in a world in which few of us are close with our neighbors or spend more than a few years in any location.

The network, which had previously been used to establish and maintain relationships, becomes reinterpreted as a channel through which to broadcast.

Networks of Resistance

In a digitally interconnected world, whoever has the most robust networks, the right relationship between visible and opaque channels, and the most persuasive narrative will triumph. Communication and coordination trump brute force when any clash can draw in a potentially infinite number of participants on either side. This is why the EZLN (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional, Zapatista Army of National Liberation) was able to stand down the Mexican state; it’s why the global uprisings of 2019-2020 spiraled out of control in over a dozen countries.

The authorities know this. The challenge for them has been that the same digital networks that maximize economic productivity by keeping all potential workers, trends, and ideas available to the market at all times can also serve as a space to coordinate resistance. Over the past two decades, they have scrambled to establish controlled networks that can fulfill the same economic function without facilitating unrest—Facebook and WeChat being among the chief examples of this.

Early on in this era, the RAND corporation theorized this kind of connectivity-based conflict as Netwar, seeing early examples of it in the Zapatista uprising and the shutting down of the summit of the World Trade Organization in 1999.

But the Zapatistas were not using Indymedia. Likewise, demonstrators were not using Twitter or even TXTmob at the protests against the WTO, the International Monetary Fund, or the Free Trade Area of the Americas. Most of the participants didn’t even have cell phones. The communications platforms that were in play when the concept of Netwar emerged were mostly 20th-century unidirectional technologies, like printing newspapers and pressing vinyl LPs, that had been repurposed to create grassroots movements.

So the most determinant factor in the victories of the anti-capitalist movement of the turn of the century was not digital connectivity, per se—it was robust networks that exceeded the control of the authorities, such as those that had emerged in Indigenous organizing, punk, environmental movements, and other cultural spaces. The intensity of the connections that people formed, and the fact that they were so difficult for the authorities to monitor, were as important as the extent to which they spread.

In the next wave of revolt, between 2008 and 2013, participants took advantage of mobile phones and emerging digital networks to gain the initiative. After Greek police officers murdered Alexandros Grigoropoulos in Athens in 2008, for example, police around Greece were taken by surprise by activists who had received the news before them. At the same time, mobile phone records enabled British police to convict a large number of participants in the riots of August 2011. The Egyptian revolution picked up momentum precisely when Hosni Mubarak shut down the internet, forcing everyone to go into the street to learn what was happening. Occupy spread digitally, including on Facebook, but drew its power from the shared physical presence of the participants. Once again, it wasn’t digital connectivity, per se, that gave these movements their strength.

The wave of movements of 2018-2020 (say, from the Yellow Vest Movement to the end of Donald Trump’s administration) did indeed draw on Twitter, Telegram, and similar platforms for coordination. Still, it’s worth noting that the specific platforms that have been essential to each of these waves of activity have changed from one wave to the next.

Extrapolating from these examples, it seems likely that the next wave of social movements will emerge as a consequence of people forging new connections on new platforms. Those platforms will necessarily develop beyond the control of people like Elon Musk. It would be simplest if those fired from Twitter would establish their own platform on a self-organized, decentralized, horizontal basis—something like Mastodon, say, but better organized. What will actually come next is hard to anticipate, but one thing is certain under capitalism: things will continue to change.

In the meantime, there are two layers to digital communication—a public layer and a private layer. The public layer serves movements as a means of informing and coordinating on a large scale; the private, of connecting and planning on a personal scale. As it becomes more difficult to utilize the public layer of corporate social media platforms, people will shift their focus to the private layer—to encrypted platforms like Signal and Matrix—and this will hopefully produce stronger and deeper connections than platforms like Instagram and Twitter could.

A contradiction: the self-regulating and self-organizing qualities of emergent networked phenomena appear to engender and supplement the very thing that makes us human, yet one’s ability to superimpose top-down control on that emergent structure evaporates in the blossoming of the network form, itself bent on eradicating the importance of any distinct or isolated node. This dissonance is most evident in network accidents or networks that appear to spiral out of control—Internet worms [sic] and disease epidemics, for instance. But calling such instances “accidents” or networks “out of control” is a misnomer. They are not networks that are somehow broken but networks that work too well.

-The Exploit, Alexander R. Galloway and Eugene Thacker

The Effects on Our Communities

In the 1980s and 1990s, anarchism made a comeback by rooting within subcultural spaces including punk, the rave scene, and various protest movements. Starting in the early 2000s, some young people treated anarchism as a subcultural milieu unto itself comprised of interlocking cliques and institutions. Most of those models began to reach their limits by the early 2010s, as scenes that had been based in tight-knit groups of friends succumbed to attrition and communities fractured over conflicts about privilege and accountability. At the same time, gentrification was rendering it more difficult to hold on to physical spaces such as social centers and collective housing projects.

By the beginning of the Trump era, many of the communities that had preceded social media had disintegrated, replaced by networks based in online connection. Coordinating through social media allowed for a more atomized social body to nonetheless respond rapidly and flexibly to unfolding events—without necessarily emerging from those experiences with stronger social ties.

The pandemic created unprecedented isolation and reliance upon digital technology. Internet use skyrocketed alongside alienation. Some of us hoped that the end of the pandemic would bring a renaissance of in-person organizing. But there was no conclusion, properly speaking, just a tapering off of security measures, with the consequence that intimate social relationships have continued to erode throughout our society.

The reactionary takeover of social media, which culminated with Elon Musk buying Twitter, will force us to renew other forms of connection. Otherwise, what we can create together will indeed be limited by the algorithms of the ruling class.

This situation is an opportunity as well as a setback. It reminds us to root our relationships in deep connection, to build affinity offline. If we are successful in fostering nourishing communities, other people will want to share these with us, as alienation and isolation have become widespread. There is life after social media.

“At a cultural level, we didn’t stop smoking just because the habit was unpleasant or uncool or even because it might kill us. We did so slowly and over time, by forcing social life to suffocate the practice. That process must now begin in earnest for social media.”

Let’s go offline together.

Some Ways to Connect besides Posting on the Internet

Spending time physically together—or at least in direct contact—is the bedrock of our relationships. If we don’t begin from strong personal connections and an ability to gather, there is nothing to network.

-

Print out some zines, acquire a few books, and set up a literature table. For the previous generation of anarchists, the classic in-person educational event was the book fair, at which a variety of publishers and distributors would hawk their wares. But you could set up a table at other events, too—protests, speaking events, punk shows, dance parties, art shows, even holiday markets. Maybe you don’t need an event at all, just a high-traffic location on a campus or at a public park or skate park.

-

Go out at night and decorate your community with stickers and posters. You can buy wallpaper paste or make wheatpaste at home yourself. You can also use stencils or other forms of graffiti to spread a message widely. You can obtain a variety of posters and stickers from us or make your own.

One of our stickers in action.

-

Organize mutual aid events, projects, and networks. The classic mutual aid project is Food Not Bombs—cooking and eating together is a time-honored way to solidify bonds. Another longstanding model is the Really Really Free Market, in which the participants establish a temporary commons based in a gift economy. The pandemic and the George Floyd Rebellion offered a range of newer frameworks for mutual aid projects. The solidarity network model offers a blueprint for how people can help each other confront typical problems with landlords and bosses. For a more informal model drawing on traditional barn raising, a group could form to assist with group projects on a rotating basis.

-

Organize dance parties! All the better if you can occupy some exciting or unusual venue to host them.

-

Organize reading groups around particular texts, discussions about ideas or public events, movie screenings, presentations, speaking tours, conferences.

-

Organize a social center to host events and provide a point of entry for curious people in your community. Maintaining a gathering space will help you meet new people and enable your community to form deeper connections. If it’s impossible to rent a space, you could establish a common gathering area in a public locatioin, or make a practice of gathering at a regular time and place. The Atlanta forest offers one example of how forest defenders have made an embattled public space into a sort of revolutionary commons.

-

Host a knitting circle, art night, or work party so you benefit from each other’s company while you tinker.

-

Organize a theater group—traditional theater, shadow puppetry, sock puppetry—or just gather to read a play aloud, the way people did in the 19th century. If you don’t have a better idea, try the works of Dario Fo.

-

Host parlor games. The surrealists developed an array of those.

-

Construct giant inflatables, homemade musical instruments, infernal machines. Carry out interruptive performance art actions at municipal events, staid gallery openings, graduation ceremonies, and the like. You can read about how others have done such things here.

-

Print handbills advertising local events. Leave them at bus stops, on the bus, at coffee shops. Put them under windshield wipers. Put them in mailboxes. Hand them to strangers.

-

Talk to people. Talk to your housemates, your family members, your co-workers, your neighbors, to people at bus stops. Invite them to events. Don’t keep to yourself with others like you in a subcultural bubble—make sure you are always interacting with new people, challenging them and yourself.

-

Most of these things can be organized in such a way as to minimize risk from COVID-19 and address other health concerns in order to keep everything participatory and inclusive. If circumstances make participating in these activities difficult for you personally, you can support others who engage in these activities, donate to social centers and distribution projects, and contribute to bail funds when people get arrested.

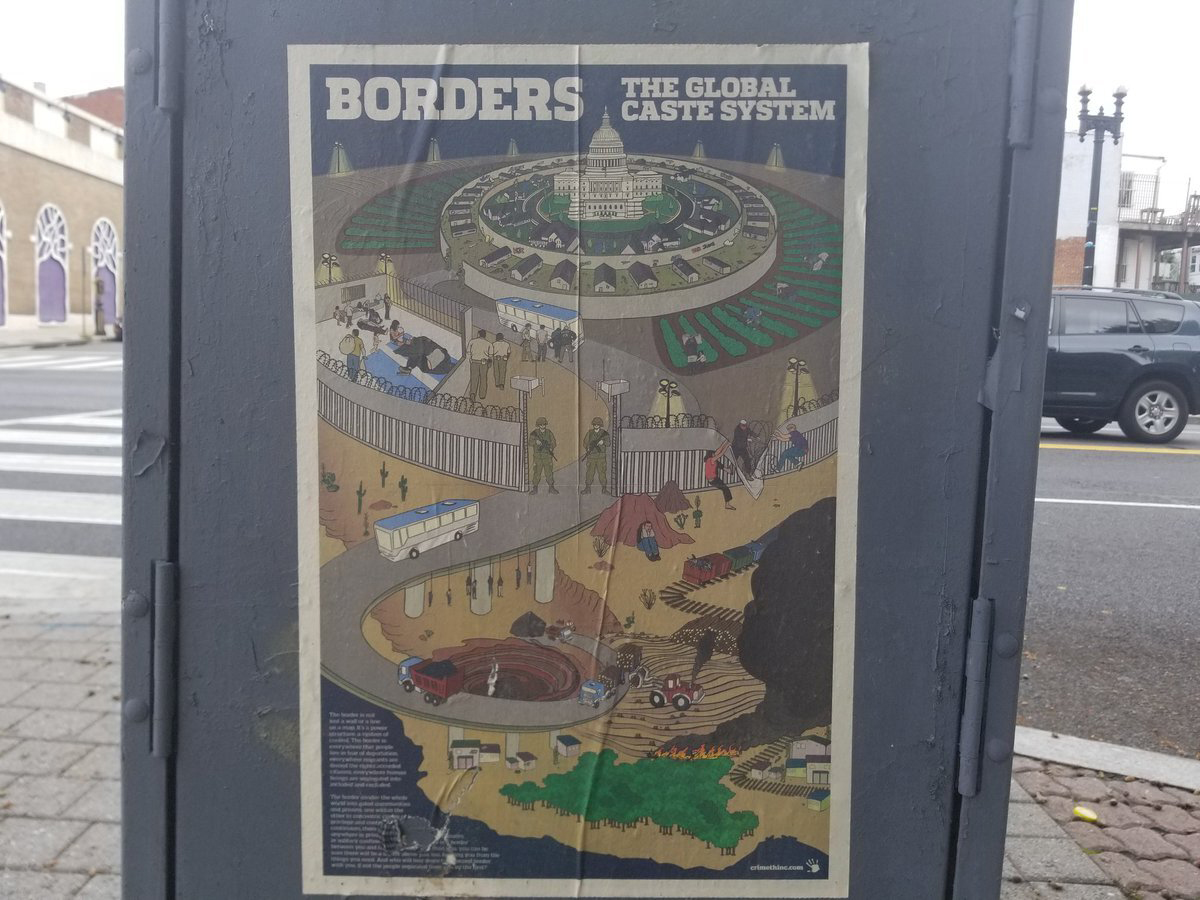

One of our posters in action.

Further Reading

- Deserting the Digital Utopia

- The Internet as New Enclosure

- The Billionaire and the Anarchists—Tracing Twitter from Its Roots as a Protest Tool to Elon Musk’s Acquisition

-

Precisely nine months after this article was published, we finally have a citation for this claim. According to a New York Times article published on September 9, 2023, “Days after Twitter’s board approved the deal, Mr. Musk told his four teenage sons that he had purchased the social network to sway the next U.S. presidential election. ‘How else are we going to get Trump elected in 2024?’ he said.” ↩

-

The richest 1% of the world’s population currently owns nearly half of the world’s wealth, and the rest of the top 10% own most of the remainder. ↩

-

In a sector of the tech market in which employees have a wider range of employment options that Tesla and SpaceX employees do, reusing the tactics he developed in the aerospace and electric car industry proved more difficult than he anticipated. Many of the employees who worked at Twitter could earn more money selling the same skills to other corporations; they stayed at the company because, to some extent, they identified with the role Twitter played in society. As soon as they received Musk’s email demanding that they be “hardcore,” most of them left. ↩