After several failed attempts across Europe to frame anarchists and other anti-authoritarians with conspiracy and terrorism charges, the Greek state is at the forefront of developing new legal strategies to attack social movements. Article 187A of the Greek legal penal code has existed since 2004, but last year, Greek officials used it in a new way against Nikos Romanos and several other anarchist prisoners, convicting and sentencing them to many years in prison based on a new interpretation of the article. Regardless of whether these verdicts are overturned in higher courts, the trials indicate a major strategic shift in the policing of social movements in Greece. They offer an important warning sign about the new forms that repression may assume around the world as social conflict intensifies.

The Greek “anti-terrorism” laws are largely drawn from United Nations and European anti-terrorism guidelines; for the most part, they were drafted in the post-9/11 period. The social-democratic PASOK government introduced the majority of Greek “anti-terrorism” legislation in 2001; at the time, it was primarily aimed at criminal organizations. In 2004, the right-wing government of New Democracy introduced a new charge: “terrorist organization.” The infamous article 187A appeared in this legislative package.

Article 187A defines the nature and scope of so-called “criminal” and “terrorist organization” and describes the role of an “individual terrorist” within an organization. In both cases, it is not necessary that an actual crime be committed to determine that an individual participated in a coordinated act against the state and should therefore be imprisoned for many years. The article gives the judge free rein to interpret the evidence provided by the police however he or she sees fit. This has already resulted in many arrests and long-term imprisonments, mostly targeting anarchists and anti-authoritarians.

When Nikos Romanos and several other anarchists faced trial last year, the prosecutor repeatedly emphasized: “They are anarchists, so their actions are terrorist.” This sentence summarizes the message that the Greek state aims to send.

Nikos Romanos.

The case of Nikos Romanos illustrates this clearly. He was sentenced to 15 years and 10 months in prison in 2014, after police arrested and brutally tortured him for expropriating a bank in Venvento, Kozani. They also accused him and five others of participating in an alleged “terrorist organization,” Conspiracy Cells of Fire; all of the accused deny this. The state failed to prove they were part of the network and consequently failed to convict them on charges of conspiracy or terrorism.

Considering the burden of proof too high for the state to imprison anarchists for participating in collective struggle, officials set out to invent a new prosecution strategy. For this purpose, the advantage of article 187A is that it prosecutes an idea. This strategy strikes at the heart of the ungovernable anarchist movement in Greece, which is based above all in a shared ethic. When Nikos Romanos faced additional charges along with his comrades in 2018, he was no longer being charged with carrying out acts of collective terrorism; rather, he was charged with being an individual terrorist on the basis of his ideas. The consequence was that he received a harsher sentence for being an avowed anarchist than he did for robbing a bank.

It is no coincidence that article 187A was first used in this way against an anarchist who saw his best friend, Alexis Grigoropoulos, murdered by police on the streets of Exarchia. Nor is it a coincidence that the authorities used article 187A against Romanos after the hunger strike he carried out in prison in 2014 triggered massive confrontations in Greece and solidarity protests around the world. The Greek authorities hope to crush the most militant current in the anarchist movement while giving others a false sense of security—as if what happens to Nikos Romanos is an isolated case of an extremist receiving an extreme punishment rather than a step towards the repression of all social movements in Greece. Essentially, prosecution on the grounds of “individual terrorism” is intended to break down any kind of form of solidarity, making people fear that if they stand up for someone who is targeted by the state, they too could be targeted as “individual terrorists.”

The only way to counter this strategy is to create an abundance of solidarity, rather than the scarcity they aim to produce. This is not just about Nikos Romanos and other specific imprisoned anarchists. It is about the future of resistance itself. And not just in Greece.

Nikos Romanos greets supporters with a raised fist through the bars of a hospital prison during his hunger strike in 2014.

We have to see the article 187A trials in a broader context. For over a century, the Balkans have functioned as a state laboratory for experiments in breeding nationalist hatred, fomenting civil war, and crushing social movements. Greece undoubtedly has one of the most thriving and confrontational anarchist movements in Europe; other countries are observing it carefully for this reason. Just as Germany exports crowd control tactics and tear gas to the south, what happens in Greece could be exported as a model to destroy movements elsewhere as well.

Following the rise and inevitable failure of left political parties like Podemos, Syriza, and Die Linke in Europe, and the equally inevitable rise of extreme right-wing and openly pro-fascist political parties and governments like we are seeing in Hungary, Austria, Poland, and Italy, centrist politicians are desperately grasping for ways to stay in power wherever they can.

The partisans of the extreme center have to demonstrate that they are the rational alternative to both the right-wing and left-wing movements. In an absurd situation in which the pro-war neoliberal Angela Merkel has apparently become the sole defender of migrants’ right to travel, it is clear that centrists aim to falsely distinguish themselves from the right via a discourse of liberal and reformist “openness” and “human rights,” while at the same time deporting migrants to war zones and depriving them of human dignity in maximum security prisons and refugee camps all around Europe.

But the centrists have to do more than simply prove themselves more rational and reasonable than the far right. They also have to show that the values of true solidarity, mutual aid, radical equality, horizontality, anti-capitalism, anti-sexism, and self-organization are not the appropriate response to the rising tide of fascist politics and the environmental and economic crises of our age. They have to figure out how to target scapegoats within the social movements. This is why they are putting anarchism on trial, not just anarchists. To retain power, they have to prevent people from developing the ability to imagine other forms of social organization beyond capitalism and the state. By introducing and expanding harsher methods of repression, the centrists are pushing us faster and faster towards a state of extreme center in which the right wing does not need to take power to implement its agenda—because the policies of the center themselves create de facto fascist results on the ground.

The trials under article 187A, the introduction of ever more restrictive laws, and the increasing impunity of police and the military around the world comprise an attack on our communities and on the possibility of collectivity itself. They are an attempt to divide, isolate, and defeat us so we will have to accept any injustice that the state imposes. In constructing the “individual terrorist” as a new target for law enforcement on the basis of ideology alone, they are threatening everyone who might dare to challenge the prevailing order.

In such circumstances, practically anyone can become the target of persecution. The only way to fight this is to stand together.

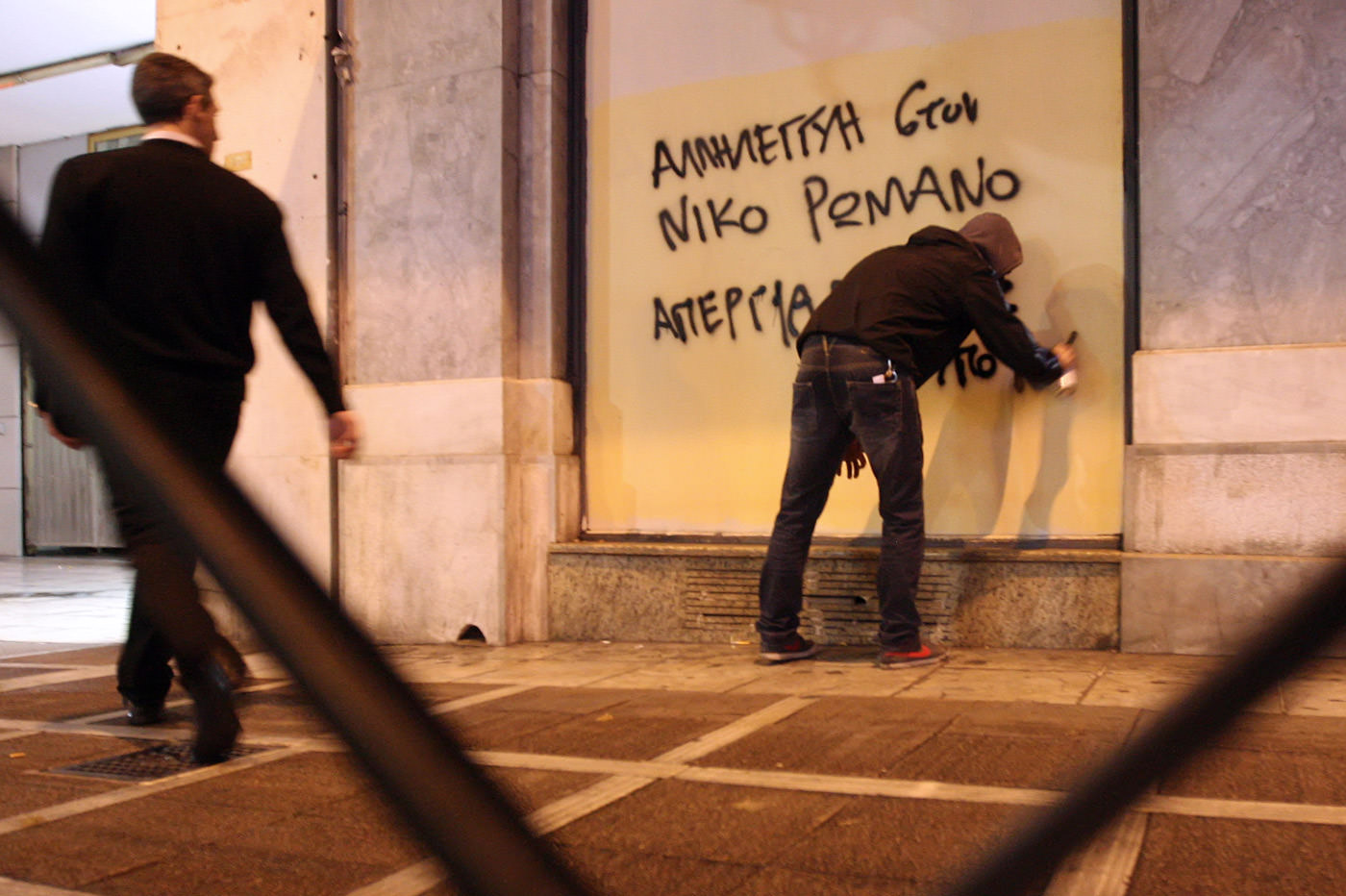

Graffiti in solidarity with Nikos Romanos.

The following interview with Nikos Romanos originally appeared in Greek in Apatris, an anarchist street newspaper in Greece. You can read more about Apatris in the appendix, below. We thank our comrades for generously translating the interview.

How is the new interpretation of the counter-terrorist law affecting your case?

Nikos Romanos: This conviction has a significant effect on us, as it means that some of us will spend two or three more years in prison. Considering that we have already been in prison for more than five years, this conviction should be seen as an attempt to create a permanent captive status based on the “counter”-terrorism law (187A). In application, this law serves the purpose of producing the specter of “internal enemies.”

Dehumanizing sentences, repressive new interpretations and arbitrary applications of the 187A law, criminalization of the anarchist (political) identity—together, these constitute a network of penal repression that methodically enfolds the anarchist movement and its imprisoned militants.

This specific conviction should not be understood as an attack against individuals. We have to recognize it as a continuation of the domestic Greek counterterrorism policy, which aims to tighten a noose around the neck of the anarchist movement as a whole.

The state is taking advantage of the fragmentation and the lack of a radical analysis that characterize both the movement and society at large to intensify its attacks.

The conviction for individual terrorism is the first of its kind in Greece. The 187A counter-terrorism law deliberately leaves a lot of space for each judge to make his own interpretation, which expands the armory that the state has at its disposal to carry out repression. How should we respond to this kind of law, and to the other convictions like yours that we can expect to follow?

Nikos Romanos: What is further equipping the state is the political nature of 187A law, which legalizes every possible interpretation of the article. Essentially, we are dealing with a law that practically implements the dogma of the US “war on terror.” This law paves the way for a ruthless witch-hunt targeting “internal enemies” and all who are seen as a threat to the state and capitalist interests.

Regarding our response to these processes, in my opinion, first, we must realize that we need an organized subversive movement. A movement that is capable of destabilizing and undermining the state and the plans of the capitalist bosses and their political puppets in our regions.

To be more precise, we have to begin a process of self-criticism analyzing our mistakes, our deficiencies, our organizing weaknesses. This self-criticism must neither flatter us nor make space for pessimism and despair. Our goal should be to sharpen the subversive struggle in every form it can take, to transform it into a real danger for every ruler. Part of this process is reconstructing our historical memory, so it can serve as a compass for the strategies of struggle we employ. We should start talking again about the organization of different forms of revolutionary violence, the practices of revolutionary illegalism, and the need to diffuse these in the movement in order to overcome the “politics” (in the dirty and civil meaning of the word) that have infected our circles.

This conversation will be empty and without effect if it isn’t connected with the political initiatives of comrades, in order to fill in the gaps in our practice and to improve our prospects on the basis of our conclusions. The best response to the judicial attacks on the movement is to make sure that those who enact them pay a high political cost for it. This should take place throughout entire pyramid of authority—everyone, from the political instigators of the repression to the straw men who implement it, should have to share the responsibility for the repression of the movement.

This response is part of the wider historical context of our time; it is our political proposition. In response to the transnational wars, we propose nothing less than a war of liberation in the capitalist metropolises, a war of everyone against everything that capitalism promotes.

Defending a social center in Thessaloniki from riot police during demonstrations in solidarity with Nikos Romanos.

How does this new interpretation of the law affect comrades in struggle outside the walls of prison who are thinking of taking militant action?

Nikos Romanos: This decision creates a really negative precedent that will increase the extent of criminal repression against anarchists who take action and have the misfortune of being captured and becoming prisoners of the Greek state. Essentially, according to this interpretation of the law, what is criminalized is the anarchist political identity. In the words of our appellate prosecutor, “What else could these acts be, other than terrorist, since they are anarchists?” With the new interpretation of “individual terrorism,” it is not necessary for judicial mechanisms to try to associate the accused with the action of a revolutionary organization, as was the case in the past. One’s political identity and taking an uncompromising position in the courtroom are enough for a person to be condemned as an “individual terrorist.” Anyone who chooses to fight according to the principles of anarchy can therefore be condemned as a terrorist as soon as their choices put them beyond the frameworks set by civic legitimacy.

Of course, this should not spread defeatism. On the contrary, it is another reason to escalate our struggle against capitalist dominance. Whoever arms his conscience to overthrow the brutal cycle of oppression and exploitation will definitely be the target of vengeful and authoritarian treatment by the regime. This does not mean that we will give up our fight, in the courtroom or elsewhere.

The fact that anarchy is a target of state oppression even in a time of the movement’s retreat should be a source of honor for the anarchist movement, proof that the struggle for anarchy and freedom is the only decent way to stand against the totalitarianism of our time.

“Partly because of their studies, partly because of their job, partly because they got “Europeanized,” some seem to forget more easily now how furious they are about the social and political stagnation of Greece. Still others shook the dust off their feet out of the disappointment that followed the wrath, promising themselves they would never look back. But then there come those moments of the ‘re-awakening,’ when the death of freedom is near and humanity loses its value. In moments like those, they imagine grabbing the first plane and going back to get down on the streets. SOLIDARITY TO NIKOS ROMANOS!”

Given the directives of the European Union and the global witch-hunt against “terrorism” since 9/11, counterterrorism law has become a major battlefield against the enemies of the Greek state, internal and otherwise. In this situation, when the state is attempting to widen the application of the law with new trials, what sort of actions should the movement take to respond to this interpretation of the law?

Nikos Romanos: For me, there is an imperative need to create political initiatives against the “counter”-terrorism law, which constitutes the battlefield of criminal law enforcement against us. We have to spread the word that this can affect others involved in struggle if their actions create obstacles for capitalist interests. They too will be charged with the counterterrorism law (187A).

For example, the residents of Skouries (Chalkidiki) were persecuted for terrorism because they took action against capitalist development and the pillaging of nature. This demands careful political analysis. It is dangerous to make two categories of people who are accused with the “counter”-terrorism law. On the one hand, the authorities are using it against those whose actions could be described as an urban guerrilla strategy; on the other hand, they are using it against people from completely different parts of society.

Calling for a front of struggle against the “counter”-terrorism law does not mean maintaining illusions that it will be abolished. Greece is a state in the European Union; it has a specific role in capitalism in the region and it is willing to unconditionally apply all EU directives on security and immigration. No matter which party is in power, Greece will not abolish the “counter”-terrorism law. The “counter”-terrorism law is inseparable from the interests of the Greek state. Therefore, the fight against 187A has to reveal precisely this connection. We have to attack both the local continuation of the American rhetoric of the “war on terror” and the mendacious narratives of the left social-democratic SYRIZA. In reality, all their talk about human rights magically ceases when the interests of the state and capitalists are in play.

A common struggle against 187A has to emphasize the internal contradictions of the system, show the role of “counter”-terrorism laws in the functioning of the EU states, and send a powerful message of solidarity to everyone around the world who is imprisoned under laws like this. This would create political issues around the invasive “counter”-terrorism crusades of our era. It would inflict permanent political damage for the criminal existence of the 187A law, the state, and capitalism, all of which poison and destroy our lives.

Establishing this offensive can offer a basis for comrades to communicate, act, and undertake a general counterattack against the capitalist complex and all its deadly tentacles. This is why I consider an initiative like this crucial for the evolution of the subversive struggles of our time.

Riots in solidarity with Nikos Romanos in Athens on December 2, 2014.

Further Reading

The Case of “Individual Terrorists” by Nikos Romanos

Appendix: Regarding the Anarchist Paper Apatris

Apatris was born in Heraklion, Crete in Greece in 2009. It was the response of some people to eviction threats against the local squat Evaggelismos in the summer of 2008. When the threats stopped, the uprising of December the same year boosted our ideas into a feasible project. It started as a local anarchist “free press” publication with a circulation of 3000; starting in June 2013, it became a nationwide project and today it is still going strong with a circulation of 15000 copies.

apatris: without a homeland, apatride, apatrido

We see Apatris as a means of spreading the word of the Anarchist, Autonomous, and Anti-Authoritarian movement everywhere. We serve to amplify the various voices of the movement in a critical way and to promote its pluralism as something positive, encouraging participation in a fertile discussion based on mutual respect and avoiding any dogmatic interpretation of the surrounding situation.

A banner in Brussels expressing solidarity with Nikos Romanos.