In the following account, a participant describes how people involved in an anarchist social center set up a haunted house last October as a fundraiser to support defendants facing RICO charges as a consequence of repression targeting the movement to Stop Cop City. This is an excellent example of how creative efforts can add a joyous element to political outreach and legal support.

“I don’t know what to say about it other than it was one of the coolest events ever. I literally felt like you could get lost in our space. I didn’t recognize where I was.”

-Participant testimony

This video offers a walkthrough of the haunted house. Watch at your own risk!

How We Made a Haunted House

Many Halloweens ago, in a galaxy far far away, our local anarchist puppet troupe (not to be confused with the other local radical puppet troupe, which also involved anarchists) hosted a haunted house fundraiser for the local books-to-prisoners project.

It was a wild success. With a sliding scale admission of just $5-10, we raised over $10,000. Dozens of anarchists artistically collaborated, improvised, and laughed together throughout two nights of performance. The haunted house attracted hundreds of townspeople who otherwise would never have set foot inside our books-to-prisoners space, or been to exposed to the abolitionist and anti-authoritarian ideas undergirding the jokes and jumps throughout the haunt.

So, years later—to be precise, at our Weelaunee Defense Society meeting last September—when someone made a passing comment to the effect that we shouldn’t limit our imaginations to only the traditional rote tasks of solidarity committees, I leaped at the chance. “Halloween Haunted Weelaunee Forest! But, uh, I can’t work on it. I’m too busy…”

In the end, I was still nailing wooden trees together minutes before opening. Not because no one else was willing, but rather because the collective’s creative energy was too electrifying to resist.

Checklist

Personnel:

- A team to hammer out a theme or narrative for your haunted house

- A team to coordinate logistics

- A team to promote the event (social media, fliers, interfacing with other projects)

- Acting crew

- Make-up and costuming crew

- Set build and safety crew

- Prop gathering and making crew

- Electrical and special effects crew (e.g., sound and lighting)

- Day-of volunteers

Materials:

- paint

- fabric

- plastic sheeting

- two-by-fours

- plywood

- chickenwire

- nails

- artificial foliage

- bones

- costume supplies

Tools:

- hammers

- saws

- drills

- paintbrushes

- staple gun

Lights and Electricity:

- black lights

- strobe lights (make sure to warn attendees in advance)

- colored gel lights

- colored LED lights

- extension cords and power strips

- fog machines

Don’t let this list intimidate you—we made our haunted house a success with the initiative of a half dozen people. That’s all it really takes to get started.

As for brainstorming props and mechanics, go to a library and check out books about how to make your own haunted house. There’s a wealth of information on the subject.

Organization

Our anarchist social center is, for lack of a better term, federated. The building has its own name, but inside it, there are half a dozen spaces, each managed by a freestanding organization or project: a community print space, a radical lending library, a queer Jewish zine archive, a co-working space for a handful of anarchist publishers and podcasts, a semi-squatted garden, a harm reduction warehouse, and a free kitchen that serves two meals a week. To pull off the haunted house, we had to get permission from each of these projects and acquaint ourselves with their preferences.

The garden and library were already reserved, as another collective had already booked those areas to throw a Halloween rager on the same night that we wanted to do the haunted house. That left us with the harm reduction warehouse, the office, the kitchen, the print shop, and the hallway between those areas.

To coordinate with the party crew, we met face to face with as many collective members as we could gather. It was hard to find time for a critical mass of us to meet, but I think it was worth it to sit down in person. There are some things that just can’t be expressed well over text, like the fact that we sincerely weren’t trying to compete with the party, we wanted to collaborate with them.

We took a different approach with the project spaces. We chose point people for each room who would be responsible both for coordinating with the regular users of their space and for bringing together the materials and design for that room in the haunted house. By decentralizing responsibility, we maximized each point person’s investment in their room and their ability to respond to the needs of those who would normally use it. The project would have been too much for one person to take on alone. It also meant that each room had its own creative vision for the scares and wonders. The results included jump scares, compressed air guns, falling spider babies, chainsaw chaser guys, and a grotesque, impaled dummy representing a cop.

Internally, we met in person for a couple of hours once a week, and established a signal thread for discussion between meetings. Both the thread and the meetings were completely open to whoever wanted to contribute. All in all, the project took about a month and a half from start to finish. It was surprisingly little work for what we accomplished. Only afterward did it become clear how much more we could have achieved with just a little more time and teamwork.

We only had one “casting call” for actors. As it turned out, this was less a matter of selecting the best actors and more a question of begging the few people who showed up to commit to the roles, days, and windows of time that we needed them to fill.

Our dress rehearsal took place immediately before we opened. It took about five runs through to start to feel confident in our rhythm.

Building Another World

Early on, we decided that all of the money raised would go to support those facing charges stemming from forest defense. We explicitly agreed not to reimburse anyone for costs or materials from building the haunted house. This was a good decision. It forced us to be more creative with our designs than we would have been if we could have essentially just bought the haunted house piece by piece from Amazon or Walmart. Some of us did spend a little money on this or that, but the vast majority of the materials were acquired through anarchist economics—they were gifted, stolen, dumpstered, returned after use, or borrowed. We even attracted two professional makeup artists from the fancy ($60 admission!) studio haunted house in town. They originally asked to be paid but quickly decided that we were cool enough for them to happily donate their time and makeup!

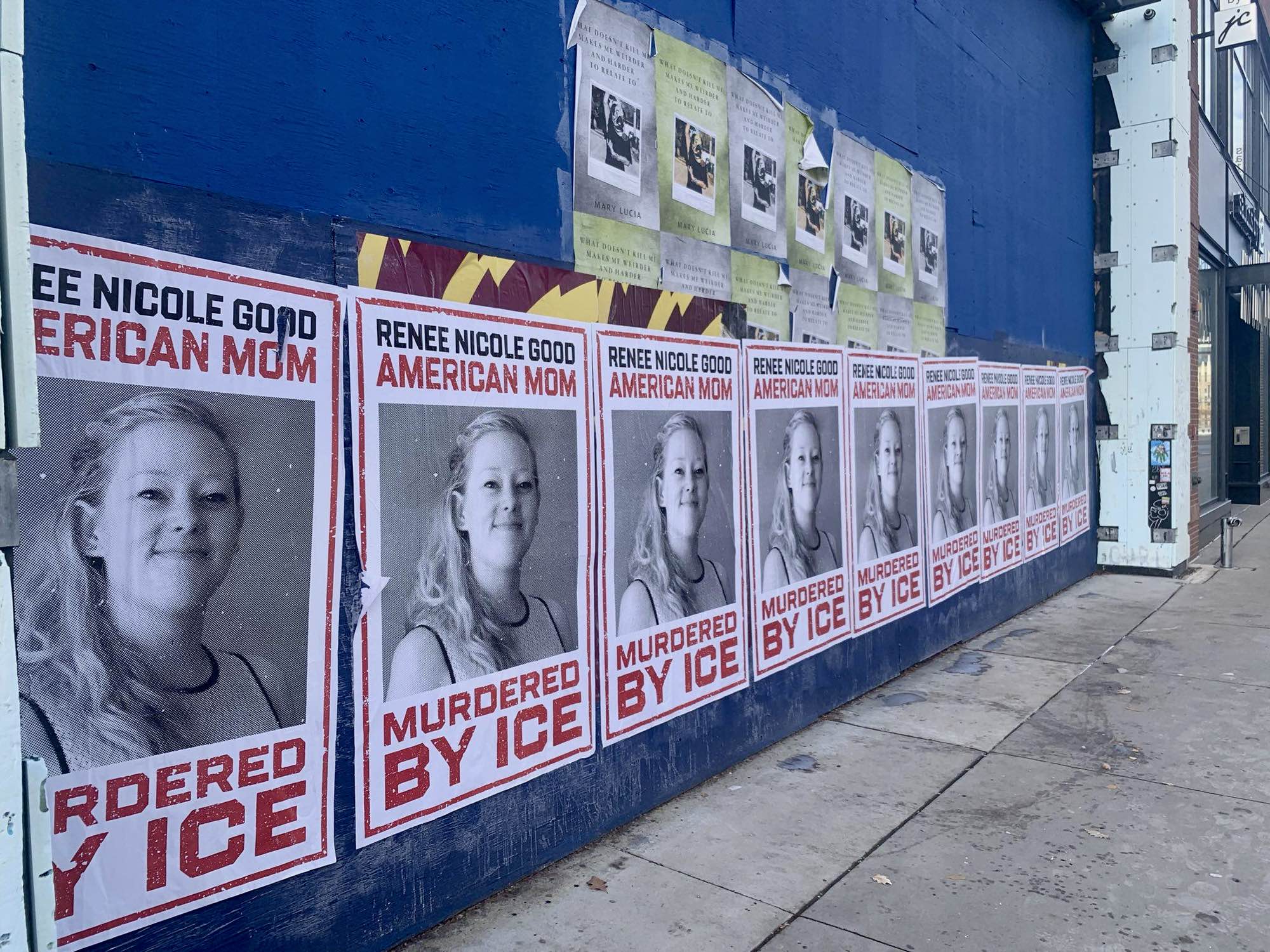

We developed the story through big group brainstorming, then we tasked one of our participants—a person who had professional haunted house experience—with synthesizing the ideas into a script. One of the bigger debates in our group was whether an absurdist work of horror was an appropriate way to represent a struggle that has already cost some people their life or liberty. It wasn’t exactly a formal decision, but those who participated most in the preparation and were actually in touch with defendants all seemed determined to make the haunt a direct reference to the ongoing struggle to defend the forest, with our sights set on building towards the Block Cop City week of action just a couple of weeks after Halloween.

We had three long build days ahead of opening. Miraculously, no one lost any of their tools in the furious clanging and banging. Often, a small team would embark on a stated task only to be pulled in by a sudden, spontaneous, fun idea that would then take hours to accomplish, morphing again and again in the course of its genesis. Almost every room saw new details added right up to the very last minute. This is a benefit of haunted houses for anarchist expression: they are spaces of maximalist chaos. The more detail, the more it confuses, the more it creates chaos, the better.

Pulling It off

In addition to the actors in the haunt, we had a Stop Cop City protester to work the crowd as they waited in line and a stage manager to check in on the actors and make sure we took a ten-minute break every hour. Those roles were indispensable. We had a line the entire night and only got all the way through it at the very end: we somehow managed to plan perfectly for the audience that showed up for us. Actors kept showing up until the end, and we managed to improvise to fill in gaps as other actors left early.

One of the highlights of the night came when a mostly Spanish-speaking group arrived to tour the haunted house. The “project manager” character started them off in Spanish, figuring that the people in the other rooms would end up using English but that it would be all right, since those rooms weren’t as dependent on narrative. Instead, from one room to the next, the people running each room heard Spanish being used in the previous room and adapted their script accordingly, resulting in a complete tour in Spanish for the group. It was beautiful to discover that we could improvise and collaborate on the basis of our affinities without making formal decisions or even being in the same room together, not to mention the analogous benefits of exercising that kind of collaborative social muscle within an anarchist community.

Room for Improvement

As in many anarchist efforts, our chief error was that we didn’t plan for success. Early on in the planning process, we decided to forego a second night on Saturday because the social center was booked for a show. As it turned out, that show lasted two hours, took place early in the evening, and did not use any of the haunted house rooms. Cast and audience alike had a blast on the night we ran the haunted house. We could easily have hosted it a second night—we would have made more money and had more fun. Part of the reason that we rushed to commit to only hosting it for one night was that we were asking a lot of the projects who lent us their space, but we should have had more faith that we would succeed in pulling off something great. Whether you’re planning a risky direct action or just a fun piece of theater with your friends, the most important question in any anarchist activity is “What if everything goes so well that we want to take it further? What will we do then?”

We reached our fundraising goal, but we easily could have made double it by raising the price of admission. Admission was basically set at $5 by making a two-for-one ticket price: $10 admission to the party, $10 for the Haunted House, or $15 for both. In reality, the Haunted House was just another activity for the party-goers, and I think they would have paid $10 or more to check it out. Everybody in our collective seemed most comfortable making the admission price as adjustable and low as possible so that no one would be turned away for lack of funds, but—in my non-expert opinion—most of the crowd could and would have gladly donated more to forest defender legal defense if prompted. With dozens of comrades facing RICO and domestic terrorism charges, we shouldn’t take any opportunity to raise funds for granted.

We had planned to publish video from the haunted house to hype up the Block Cop City week of action that was scheduled to take place just a couple weeks later. In the end, unfortunately, we just didn’t have the capacity, partly because we had done so little planning around media. Likewise, early on, we had jokingly discussed adding a hell-house-style recruitment effort at the end of the haunt. Obviously, we weren’t actually going to sit people down in the final room and ask them if they would accept militant sabotage as their one and only salvation, but we did miss an opportunity to promote the week of action or channel the interest that we generated and the bonds forged that night into some kind of action treating our local Cop City profiteers to trickery.

We also failed to make a plan for cleaning up, which ended up demanding just as much effort as preparing for the haunt had. Fortunately, the success of the haunted house won us plenty of willing volunteers the next day… but still, we should have planned better. You need people to take out the trash, but you also need places to put the trash. Many thanks to the local queer Shakespeare collective for taking the psychedelic trees off our hands. We should have reserved time to communicate with the people responsible for the spaces on the backside of the haunt. Some of them were upset with how we left those spaces, while others expressed gratitude, having enjoyed the haunted house and saying that their spaces were cleaner after the event than they had been before it. The differential between the happy people and the unhappy people was one drawback to the decentralized, point-person model of organization, in that different point people had different standards regarding what it meant to clean up.

In Conclusion

You should host an anarchist haunted house in your social center! Apart from May Day, is there a more anarchist holiday than Halloween? Dark, mischievous, occult, fun!

Our haunted house brought in plenty of people who don’t usually participate in other projects at our social center, and the crowd that attended was full of people I hadn’t seen at previous event. And a whole lot of them screamed.

You can consult an interview about the haunted house and Halloween party here courtesy of our local radical journal, Living and Fighting.