Throughout the world, mass displacement is accelerating as climate catastrophe, economic crisis, and war drive millions into exile, both within their own countries and across borders. These mass migrations are exacerbating gentrification, driving up housing costs just as real estate speculation is rendering more and more people homeless. How can displaced people continue to take political action in their new homes, establishing solidarity across ethnic lines in unfamiliar settings? In Armenia, Russian anarchists living in exile set one example, supporting Armenian refugees who had squatted the abandoned Ministry of Defense.

For background on recent social movements in Armenia, you could start here. For another example of displaced people doing powerful political organizing in a new context, read this.

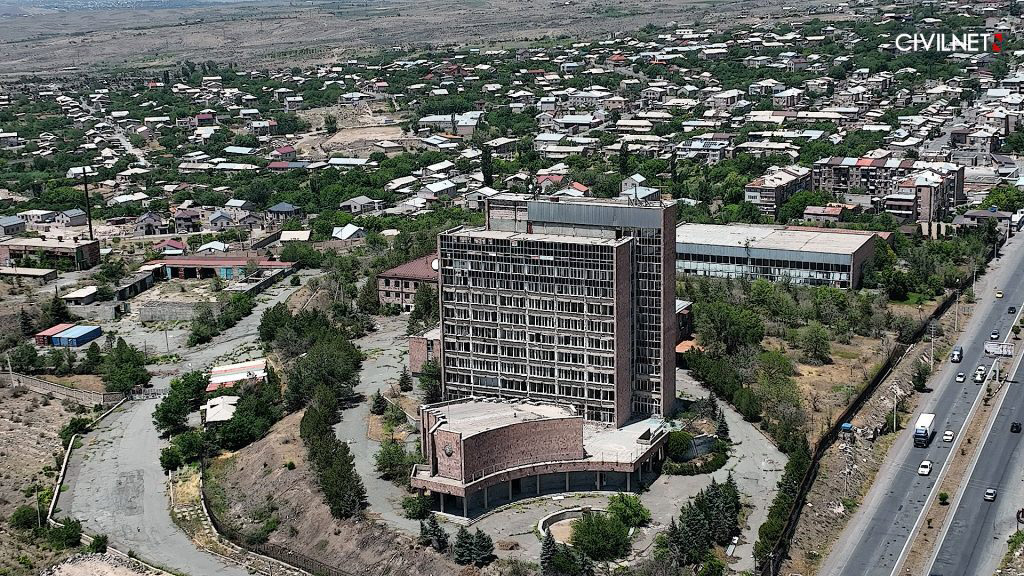

The empty windows of the evicted former Ministry of Defense building in Yerevan.

Background

The territories that were once designated by global superpowers as the “Eastern Bloc” all have their own distinct historical, social, and political trajectories. For centuries, the orientalist line between “civilized” West and “barbarous” East has been disputed here. In these territories, empires have conquered and crumbled, war and genocide have drawn and redrawn the borders.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, anarchism was at the forefront of some of the fiercest struggles in these regions. Since then, the consequences of decades of socialist rule, state repression, and brutal capitalist economic privatization in the 1990s have created a challenging political landscape. Maintaining anarchist organizing in this context has ranged from difficult (as in Poland) to extremely dangerous (as in Russia or Belarus).

We can trace the history of anarchism in Armenia back to the late 19th century. One of the most famous Armenian anarchists was Alexander Movsesi Atabekian, who was inspired by the writings of Peter Kropotkin. He was one of the early critics of the October revolution in Russia, a stance that cost him his freedom, as the Soviet authorities arrested him several times. His work remains influential, as he created one of that era’s few anarchist periodicals in Armenian.

After decades of authoritarian rule, Armenia gained independence in 1991 when the Soviet Union dissolved. The first years of independence were wracked by war, as Armenia fought Azerbaijan over the still unresolved territory of Nagorno-Karabakh.

The two decades since then have seen repeated bouts of social unrest. In 2013, a massive decentralized movement emerged in the capital city of Yerevan against the increasing cost of public transportation. A year later, self-organized protests broke out against the reform of pension system. Anarchists participated in both of these movements, and in protests against the demolition of the historic Afrikyan Club house in Yerevan. In 2015, the rising costs of electricity drew more people to the streets, once again including anarchists.

In Armenia, as in many other post-socialist countries in the region, it is difficult to make a clear distinction between protests triggered by social and economic pressures and movements seeking regime change. Nonetheless, the years leading up to 2016 saw the rise of affinity groups and small anarchist organizations, including feminist and queer initiatives.

Yet in 2016, reflecting shifts taking place around the world, the political terrain began to change, as right-wing militias snatched the initiative from anarchists. That July, they seized the largest police station in Yerevan, unsuccessfully trying to precipitate an armed insurrection. At the same time, emigration was eroding the gains that anarchists had made. As one Armenian anarchist told us then, “Leaving Armenia and joining the ranks of immigrants is currently the most widespread form of radicalization.”

In 2020, war resumed with Azerbaijan. Over the preceding years, Russia had raked in profits by selling weapons to both countries. Vladimir Putin eventually brokered a ceasefire between the two nations, but military conflict continued over the following years, escalating again after Russia became bogged down in its invasion of Ukraine. War often fosters the development of reactionary politics and far-right groups while tearing apart the social fabric that previously facilitated grassroots organizing.

In this context, it is especially important to find examples of how refugees who have been displaced from their homes and homelands can organize together, even as the previous social movements collapsed.

The former Ministry of Defense building in Yerevan.

Russian Anarchists in Solidarity with Armenian Squatters: An Interview

The following answers were provided by a Russian anarchist living in Yerevan.

Tell us about the housing crisis in Armenia.

Already, before the invasion of Ukraine, the city authorities of Yerevan were redeveloping the city, dismantling old buildings, including historic sites, and replacing them with the new structures, shops, and restaurants that are the engines of the city’s growing gentrification crisis.

After Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022, over 100,000 Russians migrated to Armenia—including anarchists. But as it turned out, there was also a war going on in Armenia itself. While Putin is officially recognized as a war criminal in The Hague, Ilham Aliyev and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the presidents of Azerbaijan and Turkey, are killing and bombing Armenians, destroying Armenian cultural monuments, and blockading Artsakh, depriving a population of 120,000 of food and medicine without any resistance from the world community.

As a consequence, in addition to Russian expatriates, Armenia has been flooded with a massive number of internal refugees, and the state has done precious little to assist them.

Landlords and real estate agents took advantage of the situation to increase rent dramatically. There were stories in the Armenian media about how refugees from Artsakh were forced to pay one and a half times more rent as a family of five in an apartment. The landlords called them and threatened to install Russians in their place, despite the fact that the terms of the lease had been discussed in advance. Sometimes, when moving in Russians, they did not remove the advertisement announcing that the space was available, but raised the price on it, threatening to evict the new tenants if they received a better offer. This contributed to the spiral of rising prices.

For the most part, landlords do not sign formal contracts with tenants, in order to be able to change the terms of rental at any time, set a new price, or kick the tenants out. This also enables them to avoid paying taxes to the government. As a result, tenants are left to fend for themselves. They have to struggle on their own, on the one hand, with landlords trying to extract the maximum profit from them, and on the other, with the economic consequences of the recent war i.

The housing crisis has affected many different demographics: students, workers from other regions of Armenia who moved to the capital, refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh, and Armenians from various other social strata.

When the partial military mobilization was announced in Russia in September 2022, a second wave of Russian migrants arrived in Armenia. This time, it included not only ethnic Russians, but also ethnic Armenians with Russian passports. As a result, even garages and basements are being hastily converted into apartments and rented out on the Yerevan market, and real estate prices in large regional cities of Armenia (such as Gyumri, Vanadzor, Kapan or Dilijan) have reached the level that prices in Yerevan reached the preceding February.

In my own experience, the problem of housing is acute for many relocated people. There are a few computer programmers who can afford an expensive apartment, but most immigrants cannot.

There is only one homeless shelter in Yerevan; it is capable of housing 100 people, whereas something like four times that many people are sleeping on the streets. Some of them have had to have their limbs amputated on account of frostbite. Yet officially, there are no homeless people in Armenia!

A fire built by evicted squatters outside the former Ministry of Defense building in Yerevan. Photo by Samson Martirosyan.

How does this relate to the eviction of the housing occupation at the old Defense Ministry?

In 2018, hundreds of people squatted a 13-story former Defense Ministry building located close to the Yerevan’s highway. It had been empty since 2008. Many of the participants were families with children, war veterans, elderly and poor people. Some of them were veterans of three or four wars. They repaired the building, planted trees, and ran a farm.

The authorities decided to renovate the space and give it to the state tax agency, which is supposed to relocate there in 2027. The idea was to create a “Foreign Economic Center” in place of the evicted squat.

Weeks before they evicted the occupation, they cut off the electricity, creating very difficult living conditions for the residents. On February 16, 2023, Armenian police came to the building and forced all the tenants out. By that time, there were at least 150 families living there. Many of the squatters fought back; 26 people were arrested on the spot. Having brought in thousands of police officers, the authorities began looting, destroying the farm and stealing things from the evictees, including military uniforms.

Twenty families have been allowed by the authorities to live in a dormitory, while others are living with relatives. But many refused to leave their home, setting up a camp on the land near the building and demanding to be allowed to continue living there.

We, the representatives of an anarchist circle that meets periodically in an anarchist bar, decided not to stand aside.

A fire built by evicted squatters outside the former Ministry of Defense building in Yerevan. Photo by Samson Martirosyan.

What was the response to the eviction and your solidarity efforts?

The eviction and our activities in solidarity with the squatters have provoked some discussion among the émigré community. Someone in one of the emigrant chat rooms wrote that these refugees and veterans were “bums who seized state property,” and he, as a taxpayer, was extremely indignant about it. In response, others made arguments about human rights. Some liberals began to argue that “in Germany or Sweden, preserving the right to housing and a decent life is a duty on the part of an official.”

For me, as an anarchist, the story of the occupation is a vivid illustration of how the people themselves, with their own labor and ingenuity, can solve social problems at the grassroots level. By ensuring social rights via non-state means, this social project avoids bureaucracy and paternalism, the chief drawbacks of the welfare system.

In many ways, social experiments like squatting can also put the existence of landlords into question. Just like medieval feudal lords, landlords do not create anything of value for society, but they are still permitted to profit on others’ labor. As one of the squatters said, “If the state can’t help us, then God help us, at least let it stop interfering and stop stealing and destroying what we’ve built.”

Laundry belonging to evicted squatters camping outside the former Ministry of Defense building in Yerevan.

In the last decade, Yerevan saw several waves of protests. Do you see people building historical knowledge and experience from one struggle to the next?

With regards to the movement of the 2010s in Yerevan, there really was a street movement in which Armenian anarchists participated. There were protests against the increase in electricity prices, an anarchist bloc participated in a demonstration on human rights day, there was an action against the gentrification of Yerevan, and an action of anarcho-feminists. But unfortunately, all of the people from that generation have either left politics, joined political parties, or gone abroad to Russia or Europe.

Today, the anarchists in Armenia are mostly emigrants from the Russian Federation. In fact, I only know two Armenian anarchists: N—, a punk musician (who became an anarchist in the early 2020s), and S—, an anarcho-feminist who lectures in our space and occasionally publishes in left-wing and anarchist magazines (who also became anarchist around that time). Neither them, alas, was connected to the movements and affinity groups of the 2010s.

There is also an anarchist from Israel: Y—, a Jewish woman who gave birth in the Crimea, repatriated to Israel, lived there for 18 years in kibbutzim and participated in the anarchist movement there (including contact with “Anarchists Against the Wall”), married an Armenian and moved to Yerevan, and decided to establish a café here with anarchist and feminist themes. The café became a gathering place for the local Jewish community (for example, at Shabbat celebrations every Saturday), as well as for the creative intelligentsia, who held public readings there.

All this continued until Russia invaded Ukraine, after which the Russian authorities began to persecute their citizens even more, and hundreds of thousands of anti-war Russians (including anarchists) fled the country.

As a result, Armenia, which was mono-ethnic for almost all the years of its independence, is now more diverse.

Subsequently, many representatives of leftist and anti-authoritarian views became regular visitors at the Mama-jan café. This offered fertile ground for the formation, on the initiative of Y—, S— (of whom I spoke above), and the Russian anarchist S—, of what was called the Emma Goldman Public School. In practice, this was a weekly meeting of anarchists and sympathizers in a small room of the café to discuss new articles as they appeared in anarchist magazines.

The door of the Mama-jan café. The second sticker says “No war” in Russian.

That is how our small circle was formed, which now represents the entire anarchist movement in Armenia.

There are many different people among us. One is actively involved in veganism and even founded his own vegan cooperative (which I also joined). Others, like one friend who is a Christian anarchist, collect humanitarian aid for the victims of the war. There is a queer anarchist group that continues to engage in street activism.

The café became a social space where we began to actively hold public lectures on various topics, such as the legacy of the Armenian anarchist Alexander Atabekian (a lecture that I presented), anarchism and ecology, the Zapatistas, and more.

A presentation in Yerevan about Alexander Atabekian.

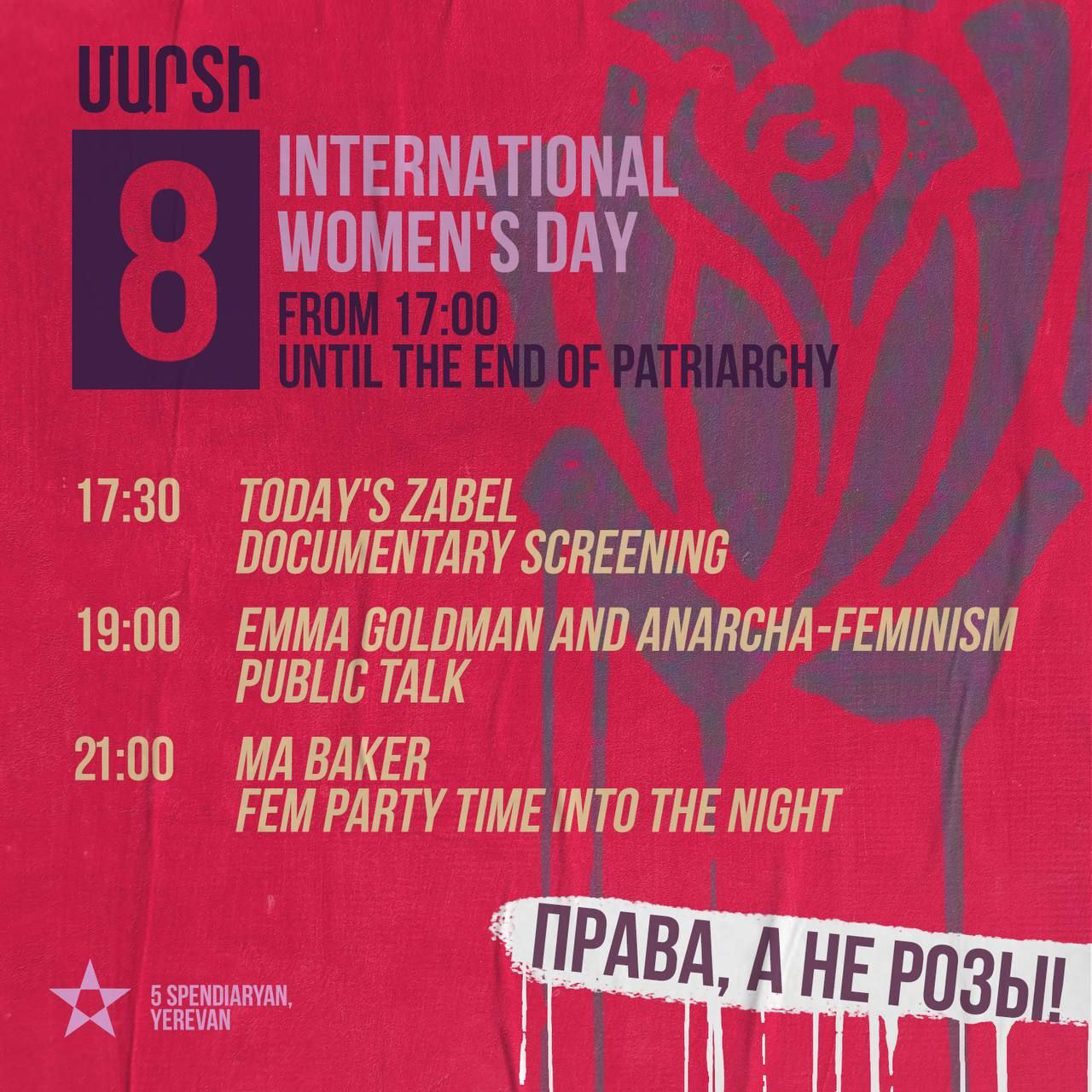

An event in Yerevan for March 8, International Women’s Day.

How did you go about supporting the squatters?

As soon as we learned that they had been forcibly evicted, we decided to go and help them. We went to them several times and, despite some initial distrust, my friends managed to find a common language with them.

As a result, at the next weekly meeting, we discussed how to go about supporting them. One of the sympathizers of anarchist ideas, a visitor to our circle, arranged to supply firewood for using potbelly stoves to heat their tents. Also, as an anti-war activist with certain connections, I managed to invite a journalist friend there. During a subsequent visit, they met us very hospitably. We helped to unload the firewood and they fed us and taught us to play backgammon.

We made a report about the situation for emigrant Russian-language media, which later played a very important role. We also established contact with the charitable organization “Ethos,” which was founded by relocators in Yerevan and is engaged in helping both Ukrainian and Armenian refugees.

Thanks to the fact that news coverage appeared about the eviction and was reposted on our initiative via various publishing houses (for example, in “Doxa,” which actively covered the persecution of anarchists and anti-war protesters), we were able to initiate a collection for food, medicine, and fuel in Ethos. In the end, we collected 60,000 drams more than planned! [The equivalent of approximately $157, still a significant amount of money for some refugees in Armenia.]

Also, the squatters began to actively invite us to their protests: they held these every Thursday and every Monday near the government building and the State Expenditure Committee. My friends and I held a poster reading “State, why did you take away people’s housing” with anarchist symbols.

The squatters were very pleased with our support, and even invited us to barbecues—which was especially ironic in the case of our vegan friend.

Now their struggle continues, and we maintain contact with them.

Camping conditions outside the former Ministry of Defense building in Yerevan.

What do anarchists have to offer to struggles for housing?

Anarchism, in principle, throughout its history, has been very interested in the housing issue. It is not for nothing that during the Paris Commune, one of the revolutionary decisions of the council was to settle homeless Parisians in the apartments of bourgeois emigrants who had fled to Versailles, and to establish a ban on evicting tenants for non-payment of rent. Housing insecurity is a significant aspect of modern society, a challenge to which anarchists must respond.

The example of this eviction is particularly striking. It shines a light on all the absurdity and immorality of a civilization based on private property.

It is necessary here to draw parallels between how Azerbaijan is trying to force out the Armenians and carry out ethnic cleansing in Artsakh, using tactics such as setting up a blockade and cutting off the electricity—and how the same thing happened in Yerevan, with the Armenian government cutting off the electricity to the squatters and creating unbearable conditions for them.

Squatters camping outside the former Ministry of Defense building in Yerevan.

The house was not built by its owner. It was erected, decorated, and furnished by innumerable workers—in the timber yard, the brick field, and the workshop, toiling for dear life at a minimum wage…

Who, then, can appropriate to himself the tiniest plot of ground, or the meanest building, without committing a flagrant injustice? Who, then, has the right to sell to any bidder the smallest portion of the common heritage?

On that point, as we have said, the workers are agreed. The idea of free dwellings showed its existence very plainly during the siege of Paris, when the cry was for an abatement pure and simple of the terms demanded by the landlords. It appeared again during the Commune of 1871, when the Paris workmen expected the Communal Council to decide boldly on the abolition of rent. And when the New Revolution comes, it will be the first question with which the poor will concern themselves.

Whether in time of revolution or in time of peace, the worker must be housed somehow or other; he must have some sort of roof over his head. But, however tumble-down and squalid your dwelling may be, there is always a landlord who can evict you…

Refusing uniforms and badges–those outward signs of authority and servitude–and remaining people among the people, the earnest revolutionists will work side by side with the masses, that the abolition of rent, the expropriation of houses, may become an accomplished fact. They will prepare the ground and encourage ideas to grow in this direction; and when the fruit of their labours is ripe, the people will proceed to expropriate the houses without giving heed to the theories which will certainly be thrust in their way–theories about paying compensation to landlords, and finding first the necessary funds.

On the day that the expropriation of houses takes place, on that day, the exploited workers will have realized that the new times have come, that Labour will no longer have to bear the yoke of the rich and powerful, that Equality has been openly proclaimed, that this Revolution is a real fact, and not a theatrical make-believe, like so many others preceding it.

-Peter Kropotkin, The Conquest of Bread

Squatters camping outside the former Ministry of Defense building in Yerevan.