What would a general strike look like today? The last two localized general strikes in the United States occurred in the same city—Oakland, California—in 1946 and 2011.1 This makes it easy to compare them in order to see what we can learn from the ways that labor struggles have changed over the past century.

Looking at the strikes of the 1940s, we can see that any combative labor resistance that breaks out today will likely emerge in defiance of union leadership rather than because of it. Looking at the general strike of 2011, we can see that to succeed, combative organizing must begin outside the workplace as well as within it, connecting the struggles of the unemployed and precarious with those of the employed. Exploring how the strategies that people experimented with in 2011 have fared in the decade since, we can draw up new proposals about what to bring to tomorrow’s uprisings.

As it has become increasingly difficult for workers to exert leverage on employers on a workplace-by-workplace basis, the general strike might represent a more ambitious way to wield power against the capitalist class as a whole.

“General strike—occupy everything—death to capitalism.” A banner in downtown Oakland on the night of November 2, 2011.

Oakland 1946

The general strike of December 1946 in Oakland was arguably the last general strike of the 20th century in the United States. As Jeremy Brecher details in Strike!, it occurred on the heels of the Second World War, during which the union bureaucracy renounced strikes.

When the United States entered the war, the leaders of both the American Federation of Labor and the Congress of Industrial Organizations pledged that there should be no strikes or walkouts for the duration of the war. Thus, at a time when profits were “high by any standard” and a great demand for labor meant “higher wages could be secured… and a short stoppage could secure immediate results,” the unions renounced the principal method by which workers could have gained from the situation.

Interestingly, the unions with Communist leadership carried this policy furthest.

Defying the united front of government and labor bureaucrats, rank-and-file workers shifted to wildcat strikes as a way to exert leverage. As Brecher recounts:

At first, the power of the government and the unions, combined with general support for the war, virtually put an end to strikes. The chairman of the War Labor Board called labor’s no-strike policy an “outstanding success.” Five months after Pearl Harbor was bombed, he reported that there had not been a single authorized strike and that every time a wildcat walkout had occurred, union officials had done all they could to end it.

Faced with this united front of government, employers, and their own unions, workers developed the technique of quick, unofficial strikes independent of and even against the union structure on a far larger scale than ever before. The number of such strikes began to rise in the summer of 1942, and by 1944, the last full year of the war, more strikes took place than in any previous year in American history.

When the war ended, capitalists were determined to regain control of the production process by suppressing wildcat strikes, while workers hoped to win wage increases to offset inflation. As a result, a new wave of wildcat strikes broke out.

Many of these wildcat strikes ultimately forced the union bureaucracy to declare official strikes. For example, immediately after the conclusion of the war, United Auto Workers requested a 30% wage increase from General Motors—but the union president declared that he hoped to reach an agreement with the management without any work stoppages. It was only after the workers at 90 plants in the Detroit area went on strike that the union ordered a strike vote, which eventually resulted in 225,000 workers walking out.

The United States Bureau of Labor Statistics called the first half of 1946 “the most concentrated period of labor-management strife in the country’s history.” Stan Weir described it as “the largest strike wave that ever occurred in the United States.”

According to Brecher,

Trade unions played an essential role in forestalling what might otherwise have been a general confrontation between the workers of a great many industries and the government, supporting the employers. The unions were unable to prevent the post-war strike wave, but by leading it they managed to keep it under control.

A scene from the Russian film Forgotten Melody for a Flute.

Altogether, 1946 saw general strikes in six cities: Rochester, Houston, Hartford, Lancaster, Camden, and—last of all—in Oakland, California.

Brecher notes that by 1946, 69 percent of production workers in manufacturing were covered by collective bargaining agreements. But unionizing efforts in the service industry had not been as successful—and after the war ended, women who had been employed in well-paid unionized production jobs were forced back into precarious service industry employment.

In the Bay Area, storeowners had their own Retail Merchants’ Association, which fought viciously to prevent the Oakland Retail Clerks’ union from organizing department store workers. Nonetheless, the momentum of the strike wave bolstered the union drive at Kahn’s Department Store, the largest store in Oakland—located downtown at the intersection of Broadway and 16th—and Hastings, the men’s store beside Kahn’s. At the same time, a nationwide maritime strike dragged on into late November in the Bay Area, creating an atmosphere of tension.

Workers at Hastings went on strike on October 21, and workers at Kahn’s joined them on October 31. In “The Oakland General Strike,” Richard Boyden describes how these strikes became a flashpoint for labor unrest:

There was strong sympathy for the strikers, most of whom were women. Not only did they receive crucial support from the Teamsters who honored the picket lines, but from the other unions, many of whose members volunteered their free time to join the strikers at the store entrances. Even before the general strike, therefore, activists—both rank-and-filers and officials—of a broad cross section of the labor movement were meeting each other on the strike scene. This contributed to a growing sense of common purpose and struggle and sentiment, as the strike dragged on, for a general strike.

According to census records, Oakland was predominantly white in 1946. It was also plagued by racial tension: the Zoot Suit Riots that had broken out in Los Angeles in 1943 had spread to Oakland as well. Nonetheless, photographs from November 1946 show an array of workers picketing in front of Kahn’s, including both Black and white workers of various genders.

According to Boyden, the local leadership of the Teamsters union “covertly opposed the Kahn’s-Hastings strike, but was prevented from acting on this opposition by its own membership.” As Boyden puts it,

The Retail Clerks’ union had always relied on Teamster support in strikes because retail workers are relatively unskilled and easily replaced. The stopping of deliveries, therefore, often is the key to success.

Blocking deliveries remains a crucial element of today’s strikes.

On Sunday, December 1, starting before dawn, 400 Oakland police officers shut down the pickets around Kahn’s and Hastings, attacking the picketers with billy clubs and cordoning off the area. As thousands watched, the police accompanied a professional strike-breaking team from Los Angeles in delivering merchandise to the two department stores. The cops towed away the cars belonging to picketers and set up machine guns in the middle of the square facing Kahn’s.

In response, streetcar operators and bus drivers abandoned their vehicles downtown, removing the steering mechanisms, effectively blockading traffic. Union organizers gathered at the Labor Temple to discuss the situation. The president of the Teamsters’ local demanded that the assembly announce a general strike immediately, declaring that his union would strike the next day regardless. A larger meeting was planned for Monday.

Oakland police stand guard as strikebreakers’ trucks deliver goods to Kahn’s department store on December 1, 1946; a line of Key System streetcars abandoned on Telegraph Avenue by their operators.

The next day, thousands of people gathered to reinforce the pickets around the stores. Union officials gathered at 10 am for what must have been a contentious meeting, judging by the fact that the call for a strike did not come out until 10 pm that night. According to Boyden, union leaders were propelled forward against their will by popular outrage: “They were frightened—first by the specter of anarchy, which seemed to grow every minute, and by the possibility of repression and reprisals.”

On Tuesday morning, Boyden writes,

The industrial and residential districts of Oakland, Alameda, San Leandro, and Hayward were silent, the streets empty… Twenty-thousand people came downtown to join the pickets. Some workers joined the strike in organized contingents, marching from their union halls.

Police attempted to establish a line in front of Hastings again, but Teamsters ran them off. Picketers also intervened when reporters attempted to take photographs in the streets (an important precedent to recall today in the age of livestreaming).

According to participant Stan Weir,

A mass of couples danced in the streets. The participants were making history, knew it, and were having fun. By Tuesday morning, they had cordoned off the central city and were directing traffic. Anyone could leave, but only those with passports (union cards) could get in. The comment made by a prominent national network newscaster, that “Oakland is a ghost town tonight,” was a contribution to ignorance. Never before or since had Oakland been so alive and happy for the majority of the population…

In all general strikes the participants are very soon forced by the very nature of events to themselves run the society they have just stopped. The process in the Oakland experiment was beginning to deepen. There was as yet little evidence of official union leadership in the streets.

Massive crowds gather in front of Kahn’s department store on December 3, 1946.

Restaurants opened as usual that morning, but the Teamsters shut down all of the unionized ones by 8 am. Some people set up a soup kitchen downtown, but it was not able to feed the tremendous number of people who had gathered. In 1946 as today, sufficient infrastructure is fundamental to any mass mobilization.

Well over 10,000 people convened at the Oakland Auditorium that night for a meeting; an overflow crowd of thousands stood outside in the rain, listening to the proceedings over loudspeakers. The prize for rhetoric goes to Norwegian-born American Federation of Labor organizer Harry Lundeberg:

“This,” said Lundeberg of the police action, “is fascism in America.” The Los Angeles strike breakers were “…just the average finks,” he shouted: “…the super finks are the city administration… These finky gazoonies who call themselves city fathers have been taking lessons from Hitler and Stalin.”

Lundeberg had spent the earlier part of 1946 engaging in red-baiting attacks on the rival Congress of Industrial Organizations during the maritime strike, but in the heat of the moment, all was forgotten. The next day, there were 35,000 people downtown for the pickets.

In response to the strike, the head of the Retail Merchants’ Association reached out to the leadership of the Teamsters. The upper echelons of the union leadership, it turned out, were more sympathetic to the employers than they were to rank-and-file workers. Dan Tobin, President of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, announced that “The International Brotherhood of Teamsters is bitterly opposed to any general strike for any cause. I am therefore ordering you and all those associated with you who are members of our International Union to return to work as soon as possible.”

West Coast Teamster boss Dave Beck complained that “This damn general strike is nothing but a revolution. It isn’t labor tactics. It’s revolutionary tactics.”

Stan Weir attributes the failure of the strike to spread beyond predominantly white demographics to the fact that the Congress of Industrial Organizations, the only organized labor contingent in the Bay Area headed by leaders sympathetic to the Communist Party, effectively stood aside throughout the events. (This didn’t prevent reactionaries from attempting to associate the general strike with the Communist Party afterwards.) If we accept Weir’s account, racial divisions played a role in limiting how far the strike could spread, but chiefly as a consequence of the concentration of power in the hands of leaders who had different goals from the ordinary workers under them.

On the evening of Wednesday, December 4, the American Federation of Labor committee met with the department store owners until 4 am. At 10:30 am the next morning, the AFL representatives voted to end the strike.

Rank-and-file workers were outraged. Some continued picketing and convened local union meetings to try to keep the strike going. According to Stan Weir,

The people on the street learned of the decision from a sound truck put on the street by the AFL Central Labor Council. It was the officials’ first really decisive act of leadership. They had consulted among themselves and decided to end the strike on the basis of the Oakland City Manager’s promise that police would not again be used to bring in scabs. No concessions were gained for the women retail clerks at Kahn’s and Hastings Department Stores whose strikes had triggered the General Strike; they were left free to negotiate any settlement they could get on their own. Those women and many other strikers heard the sound truck’s message with the form of anger that was close to heartbreak. Numbers of truckers and other workers continued to picket with the women, yelling protests at the truck and appealing to all who could hear that they should stay out. But all strikers other than the clerks had been ordered back to work and no longer had any protection against the disciplinary actions that might be brought against them for strike-caused absences.

By Friday, the general strike was over, sabotaged from above. At noon that day, 25 strike-breakers were brought into Kahn’s. Picketers responded angrily, but the union leadership once again deescalated the situation by calling for a mass meeting at the Labor Temple, enabling the strike-breakers to get into the department store without a confrontation.

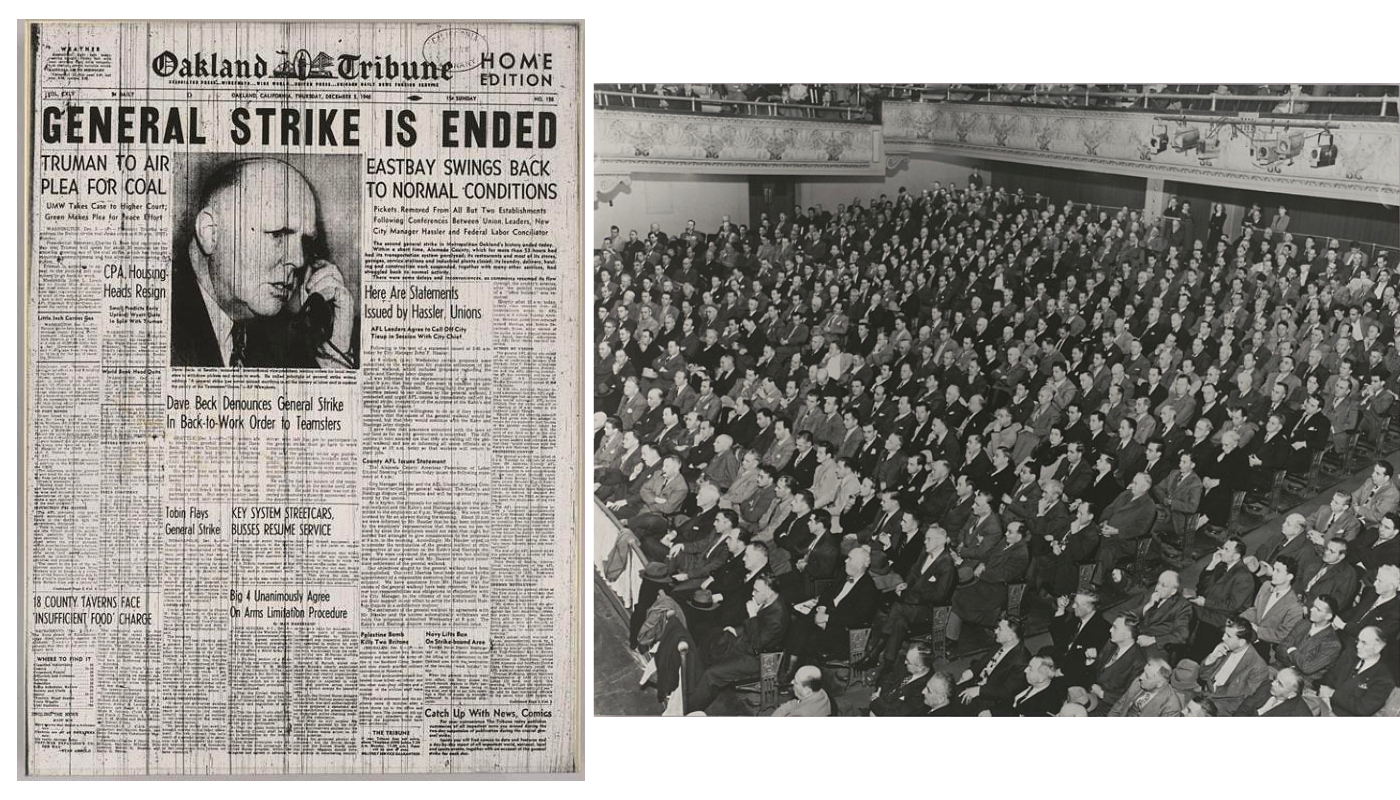

The Oakland Tribune announces the end of the strike on Thursday, December 5; the Oakland Auditorium on the afternoon of Friday, December 6, 1946, as 1200 employers met to discuss the strike.

Six months later, the workers at Kahn’s and Hastings were still out on strike.

According to Boyden, Teamster bosses like Dave Beck exemplified the sort of profiteers who professionalized the union bureaucracy, transforming it into a junior partner of the capitalist class:

[Beck] rightly viewed the general strike as a revolutionary tactic, and opposed its use no matter what the situation. He was a business unionist par excellence and a professional anti-communist. He sought to build and consolidate his organization by “selling” the conservative Teamsters union to the employers as a “responsible” alternative to militant and/or radical unions…

Beck viewed the union as a business, not a cause. He wanted to “Taylorize” the labor movement, apply to it the business methods developed by the corporations and create in the person of the union official a new professional, whose position and power rested in expertise and efficiency, not on the democratic participation of the union members. And Beck treated his union like his own company. He used his profits from the Teamsters to become a millionaire, investing extensively in Seattle real estate and other business ventures. There was no place in this scheme for militant trade unionism.

The tensions that lingered in Oakland after the general strike were channeled into electoral politics. The rival American Federation of Labor and the Congress of Industrial Organizations united to form a Political Action Committee to run candidates for the Oakland City Council. The strikes at Kahn’s and Hastings ended with a compromise the day before the elections. Four of the labor candidates were elected, though they were always outvoted by the other five City Council members. In any case, according to Stan Weir, “The four winners were by no means outspoken champions of labor. They did not utilize their offices as a tribune for a progressive labor-civic program.” Looking back, Weir realized that Harry Lundeberg, in his “finky gazoonies” speech, had begun to shift workers’ attention away from a direct struggle against employers to a focus on City Council.

After the general strike in Oakland, it was all downhill for labor struggles in the United States. Workers never again regained the leverage they had wielded during the general strikes of 1946.

President Harry Truman’s Executive Order of March 21, 1947 required that all federal civil-service employees be screened for “loyalty.” That June, Congress introduced the Taft–Hartley Act, prohibiting wildcat strikes, solidarity strikes, secondary boycotts, secondary and mass picketing, and closed shops. Union leaders were required to file with the United States Department of Labor declaring that they did not support the Communist Party and had no relationship with any organization seeking the “overthrow of the United States government by force or by any illegal or unconstitutional means.” The years that followed saw the second Red Scare, including the rise of the Federal Bureau of Investigation under J. Edgar Hoover and the imprisonment, firing, blacklisting, interrogation, and persecution of countless thousands of workers and organizers. All of these served to hamstring the labor movement while contributing to the ascendancy of its most reactionary elements. This occurred long before globalization enabled capitalists to sidestep unionized labor forces entirely, though the taming of the labor movement helped to pave the way for that. By the end of the twentieth century, subsequent waves of white flight, deindustrialization, gentrification, and the shift of the majority of wage earners into non-unionized service industry jobs had utterly transformed Oakland and other cities like it.

To those who have participated in the social upheavals of the early twenty-first century, many aspects of the story of the general strike of 1946 will be familiar: police brutality as the spark that catalyzes a contagious uprising, the ingenuity and initiative of the participants (Stan Weir described striking workers as “people who have been released from the necessity to hide their feelings”), the challenges of coordinating to meet the needs of a revolt that interrupts capitalist logistics without replacing them, the retreat into electoral politics during the waning phase.

The part that may be surprising for those who grew up after the heyday of the old labor movement is the extent to which the union leadership worked directly with the capitalist class to suppress the strike. The decades of labor organizing that had created these unions built the shared consciousness and commitments that made the strike possible, but the union hierarchies were among the chief threats to the movement itself. Today, as a new generation seeks tools with which to stand up to the capitalist class, we should not forget the lessons of 1946. Formal unions do not suffice to enable workers to stand up for themselves. The important things are organizing, solidarity, and audacity, outside of the workplace as well as inside it. The official recognition of a union—however hard won—will not automatically deliver those things, and is no substitute for them.

In 1946—as today—the power of a strike did not derive simply from the fact that workers stopped working in a given workplace. The power of the strike derived from their determination to shut down that workplace, to defend themselves against strike-breakers and police, and to interrupt business as usual on all fronts—and from the fact that when they did these things successfully, it was contagious, drawing in the participation of many people who did not share their workplace or their immediate concerns.

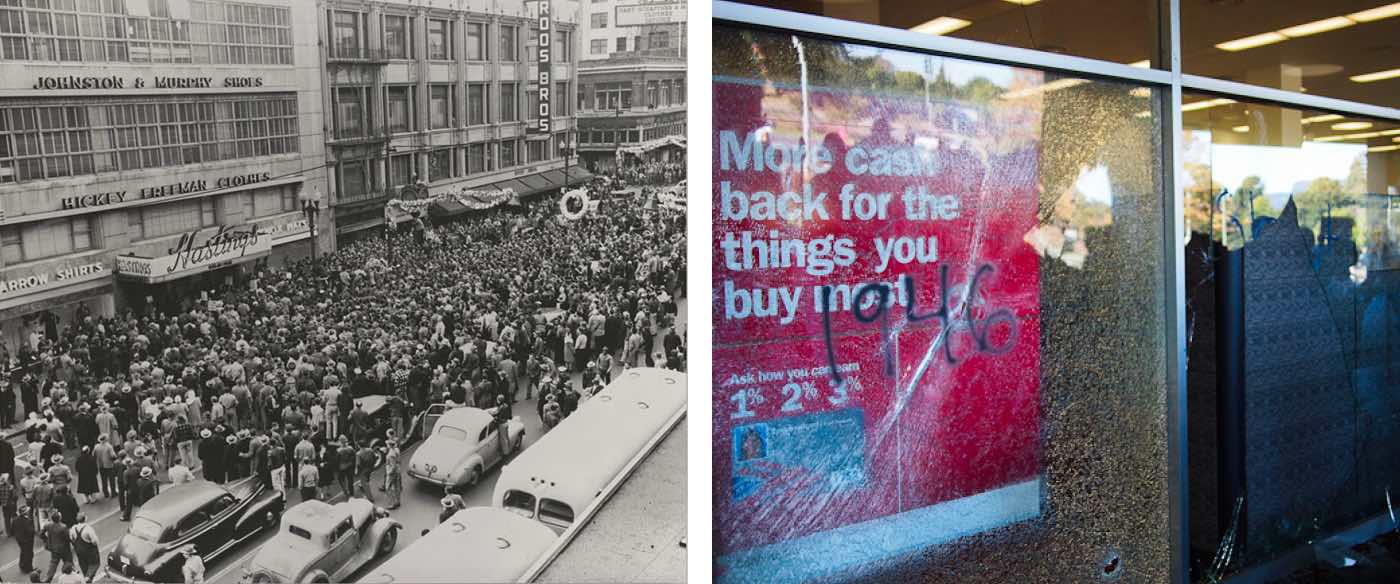

Strikers gather in front of Hastings department store on December 3, 1946; graffiti on the smashed window of a Bank of America on November 2, 2011.

Oakland 2011

After 1946, decades passed before anything like a general strike took place again in the United States. Besides the “Day without an Immigrant” protests of May 1, 2006—a subject for another study—the closest thing to a successful general strike in the United States thus far in the 21st century arguably took place in Oakland on November 2, 2011, at the high point of the Occupy movement.

The strike of November 2, 2011 differed from the general strike of 1946 in several instructive ways. Rather than mobilizing card-carrying union members to shut down their own workplaces, a motley assemblage of students, precarious workers, unemployed people, radicals, and other rebels set out to shut down the city from outside the economy proper.

Three years into the recession, the year 2011 opened with the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions, followed by the plaza occupation movements in Spain and Greece—setting the stage for sluggish social movements in the United States to finally kick into gear.

The revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt inspired people around the world in 2011. In this photograph, demonstrators wave an Egyptian flag during the port blockade in Oakland on November 2, 2011.

Though rapidly gentrifying, Oakland had not entirely lost its character as a longtime hotbed of radical activity. If few recalled the strikes of 1946, the legacy of the Black Panther Party and other radical groups from the 1960s and ’70s lingered in the popular imagination. At the same time, the local government was comprised in part of alumni of the previous generation of activists, who were experts at co-opting and pacifying social movements.

Riots had broken out in Oakland at the beginning of 2009 in response to the murder of Oscar Grant by Bay Area Rapid Transit police. Afterwards, a combative student movement took off in the Bay Area with a series of building occupations; it peaked on March 4, 2010 in a mass march from Berkeley to Oakland that ended with a breakaway march blocking the freeway. Anarchists carried a reinforced banner in that march reading “Occupy Everything”—an image from the future. In the buildup to March 4, some people had talked about calling for a general strike, but no one had a clear idea of what that could look like.

Anarchists participating in the March from the University of California at Berkeley to downtown Oakland on March 4, 2010.

In February 2011, in response to a bill stripping public-sector unions of collective bargaining rights in Wisconsin, demonstrators in Madison occupied the capitol. Again, there was some talk about calling for a general strike. On April 4, longshore workers from Local 10 of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) shut down the ports of San Francisco and Oakland in solidarity with workers in Wisconsin.

A poster promoting the idea of a general strike during the protests in Madison, Wisconsin in early 2011: “General strike means nobody and nothing works.”

In summer 2011, seeking to revitalize local networks and experiment with new tactics, a small number of anarchists and anti-state communists organized a series of anti-austerity demonstrations dubbed Anticuts. As participants later recounted,

The third and final Anticut action—organized in solidarity with a hunger strike in California prisons—marched from the future home of Occupy Oakland in Frank Ogawa Plaza down Broadway past the police headquarters, courthouse, and jail, holding a noise demo there before circling back towards the plaza to disperse. This small demonstration marked the first time this loop was tried. Months later, during the high-tension moments of Occupy Oakland, that march route became intimately familiar to thousands of people, sometimes repeated multiple times per day.

In following this march route, the Anticuts demonstrators started by City Hall—from which the police had attacked the pickets on the morning of December 1, 1946—then passed by the site where Kahn’s department store had been, and then, a block later, crossed the intersection where the first streetcar driver had abandoned his vehicle in protest that morning sixty-four and a half years earlier.

While the strikers of 1946 focused on asserting their interests in their workplaces, the Anticuts demonstrators focused on the control of public space, the defunding of libraries and other public resources, and the prison-industrial complex. Work itself had become more precarious and diffuse in the intervening decades to such an extent that it had become easier to take on other aspects of capitalism. The demonstrators confronted the conditions of their survival rather than seeking to negotiate better rewards for participating in production.

On September 17, a thousand people responded to a call to occupy Zuccotti Park in New York City. The original proposal was to gather in imitation of the Tahrir Square demonstrators in Cairo and agree on a single demand to present to the government; the editor of Adbusters, the magazine that first published the call, said “We’re hoping it’s something specific and doable, like asking Obama to set up a committee to look into the fall of US banking.” Occupy Wall Street began as form without content, a calculated attempt to create a memetic imitation of overseas movements. Owing to the involvement of anarchists like David Graeber, however, the movement adopted a horizontal, participatory structure that enabled it to surpass the vision of those who had founded it.

Across the United States, activists with a wide range of agendas and ideologies established copycat occupations. One of the first of these appeared in San Francisco. Occupy Oakland began weeks later; this gave the participants time to discuss the character of the other occupations around the country and identify what they wanted to do differently. “If this movement is to bring any fundamental change in the quality of our lives,” argued one participant ahead of the first gathering, “it must be drastically different than any of the other Occupations [sic] around the country.”

Despite rain, a thousand people gathered on October 10 in front of Oakland City Hall at Frank Ogawa Plaza, rechristened Oscar Grant Plaza—one block from the site of Kahn’s Department Store. The camp drew together participants in many earlier struggles in the Bay Area, augmenting their commitments and experience by connecting them with a broader social body.

“From the start, Occupy Oakland immediately rejected cooperation with city government officials,” the authors of “Who Is Oakland?” noted. In contrast to Occupy groups elsewhere around the United States, Occupy Oakland involved large numbers of people who were uncompromisingly opposed to the police and to reformist strategies; many participants defended the legitimacy of autonomous action, rejecting the idea that the assemblies should exert centralized control over the movement through formal consensus process.

“Worker solidarity: no compromise with bosses or politicians.” Banners at Oscar Grant Plaza during Occupy Oakland.

According to an early report from participants,

On the very first day, the camp had a fully functional kitchen, an info-tent, and a supply tent. By the end of this week there was a medic tent, art supply tent, an insurrectionary library, a free store, the Raheim Brown Free School, a media tent, a POC tent, a Sukkah, a DJ booth, and not to mention hundreds of sleeping-space tents. In addition, the rotating kitchen crew has been feeding everyone consistently from 8 am until midnight and throwing spontaneous BBQs.

The two dozen tents that had appeared the first night increased to one hundred and fifty tents by the end of the first week. Participants described the occupation as a liberated zone, while rival elements of the power structure sought to co-opt or suppress it. According to the authors of “Who Is Oakland?”,

The press releases of the city government, Oakland Police Department, and business associations like the Oakland Chamber of Commerce continually repeat[ed] that the Occupy Oakland encampment, feeding nearly a thousand mostly desperately poor people a day, was composed primarily of non-Oakland resident “white outsiders” intent on destroying the city. For anyone who spent any length of time at the encampment, Occupy Oakland was clearly one of the most racially and ethnically diverse Occupy encampments in the country—composed of people of color from all walks of life, from local business owners to fired Oakland school teachers, from college students to the homeless and seriously mentally ill. Unfortunately, social justice activists, clergy, and community groups mimicked the city’s erasure of people of color in their analysis of Occupy, when they were not negotiating with the mayor’s office behind closed doors to dismantle the encampment “peacefully.”

From the beginning, the Occupy Oakland encampment existed in a tightening vise between two faces of the state: nonprofits and the police. An array of community organizations immediately began negotiating with city bureaucracies and pushing for the encampment to adopt nonviolence pledges and move to Snow Park (itself later cleared by OPD despite total compliance of individuals who settled there). At the same time, police departments across the Bay Area [were] readying one of the largest and most expensive paramilitary operations in recent history.

In the early hours of October 25, Occupy Oakland became the first Occupy encampment in the United States to be raided in a full-scale police operation. According to the authors of “The Rise and Fall of the Oakland Commune,”

After the Commune repeatedly resisted attempts by the city administration to assert control over the camp—staging public burnings of warning letters during general assemblies in the amphitheater on the steps of city hall—Mayor Jean Quan authorized the militarized police operation that left the camp in ruins and over 100 in jail.

Later that same day, thousands of enraged people poured back into downtown, charging police barricades around the plaza and braving countless barrages of tear gas and projectiles until the early hours of the morning. Partly because of the near murder of Iraq War veteran Scott Olsen by a police projectile that night, and the dramatic footage of the entire downtown area covered in gas, the next day the police withdrew in a storm of controversy. Exultant crowds reoccupied the plaza, holding an assembly of 2000 people—the largest of the whole sequence—and agreed to go on the offensive with the November 2 strike. The fact that it seemed possible to organize a general strike in a single week indicates the degree to which normal calendar time warped and stretched in those first three weeks.

According to “Insurrection, Oakland Style: A History”:

A general assembly was called for 6 pm on October 26. The police were nowhere in sight, but some reported that they were massing at a nearby parking garage. They were never to mobilize in any show of force. Bike patrols were passing back information, and a general feeling of safety permeated the camp. The metal fence that had been set up by the city was taken down, and once again the plaza was in the hands of #OccupyOakland. A proposal was submitted for a general strike in Oakland on November 2. The proposal passed by 96.9%; 1484 votes for to 77 against, with 47 abstentions, more than enough in Oakland’s modified consensus of 90% for the proposal to pass.

96.9% was a considerable majority out of one of the largest assemblies to take place. But the population of Oakland totaled almost 400,000, and the participants in Occupy were arguably among the less steadily employed residents of Oakland: many of them were unemployed, while others were employed in the gig economy or other precarious labor. The general strike of 1946 had involved more than 100,000 workers. How could a couple thousand people pull off the same thing?

A pumpkin at Oscar Grant Plaza announcing the forthcoming general strike.

In 1946, a significant part of the population of Oakland had been unionized; in 2011, something like 89% of workers had no unions, and most of the unions that remained had been thoroughly integrated into the smooth functioning of the economy. The general strike of 1946 drew its force from the fact that, without workers, the Oakland economy ground to a halt; in 2011, in the midst of a continuing recession, most workers were employed in sectors of the economy that were hardly essential to its functioning. How do baristas, dishwashers, dog-walkers, sex workers, medical study lab rats, self-employed graphic designers, grad students, and those who seek employment on Craiglist make an impact by not working for a day?

By shutting down the economy from outside.

But how?

The announcement of the November 2 general strike.

Of course, not everyone involved in Occupy Oakland was a precarious worker. Some were connected to the same ILWU local that had shut down the ports on April 4. Elements in the nurses’ and teachers’ unions were also sympathetic to the movement. Negotiations ensued with and within Bay Area unions ahead of November 2.

By Friday, October 28, fault lines were emerging. Representatives of the ILWU and other unions announced that they would not call on their members to strike. “However energetic we are about the cause, we also are law-abiding organizations that are very cautious,” Matthew Goldstein, president of the union representing faculty at four East Bay schools in the Peralta Community College District, told reporters. “A general strike on the order of the 1946 general strike in Oakland is an ambitious goal, especially in just a few days.” (As we have seen, the 1946 general strike broke out in two days, whereas Occupy Oakland had given themselves a week to organize.)

“Only a few unions, such as the SEIU (public sector) gave an official call-out for their members to take a day off in order to participate,” the Rust Bunny collective recounted afterwards, noting that the Service Employees International Union struck a tacit agreement with City Hall to that purpose. Many unions informally encouraged their members to participate in the day of action without calling for a strike, neither wishing to risk losing credibility nor to face the legal consequences of an illegal strike.

“It’s virtually impossible for any union to endorse a work-stoppage because all contracts have no-strike clauses, which unions are bound to honor,” ILWU communications director Craig Merrilees told reporters.

That same day, Jack Heyman, a retired Oakland longshoreman and chairman of the Transport Workers Solidarity Committee, speaking at Zuccotti Park to Occupy Wall Street, declared, “Longshore workers are attempting to shut down the ports in the Bay Area. We will be calling on other workers in other ports to join us.”

At Occupy Wall Street on Friday, October 28, 2011, Jack Heyman announces the solidarity of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union with the Occupy Oakland’s call for a General Strike on November 2 in response to police violence against protesters in Oakland.

The ILWU had a longstanding clause in their contract permitting them to refuse to cross a picket line and cancel a shift if the situation was deemed unsafe. Radicals within the ILWU encouraged participants in Occupy Oakland to set up picket lines at the Port of Oakland in order to enable them to activate that clause. This approach relied upon the precarious and unemployed to enable unionized workers to walk off the job without suffering the consequences of breaching their contracts. It represented an ambitious effort to integrate the unionized working class and the precarious underclass into a single unified strategy. As we shall see, this strategy had drawbacks of its own.

Years earlier, in Washington, DC, anarchists mobilizing against the meetings of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank had called for a “People’s Strike” on September 27, 2002 to shut down the nation’s capital. Though only a few thousand protesters turned out for the day’s action, their militant messaging achieved the goal in advance: the government advised people not to ride the metro or come downtown to work, and the police themselves surrounded and effectively shut down many of the targets in their efforts to secure them. In Oakland in 2011, the call for a general strike had similar effects. A spokesman for the University of California Office of the President in downtown Oakland announced the office would be closed on November 2 and that the 1300 employees who worked in the building would work from home, for fear that the Bay Area Rapid Transit system might be impacted. The mayor gave city employees permission to take November 2 off—with the exception of police.

On November 1, the Oakland Police Officer’s Association took the unusual step of publishing an open letter criticizing the mayor and hinting at a strike of their own:

We represent the 645 police officers who work hard every day to protect the citizens of Oakland. We, too, are the 99% fighting for better working conditions, fair treatment and the ability to provide a living for our children and families. We are severely understaffed with many City beats remaining unprotected by police…

On Tuesday, October 25th, we were ordered by Mayor Quan to clear out the encampments at Frank Ogawa Plaza and to keep protesters out of the Plaza. We performed the job that the Mayor’s Administration asked us to do, being fully aware that past protests in Oakland have resulted in rioting, violence, and destruction of property.

Then, on Wednesday, October 26th, the Mayor allowed protesters back in—to camp out at the very place they were evacuated [sic] from the day before.

To add to the confusion, the Administration issued a memo on Friday, October 28th to all City workers in support of the “Stop Work” strike scheduled for Wednesday, giving all employees, except for police officers, permission to take the day off.

Meanwhile, a message has been sent to all police officers: Everyone, including those who have the day off, must show up for work on Wednesday.

Conflicts within the halls of power are often a crucial element in successful revolutionary mobilizations. The police carried out a sort of strike of their own on November 2, almost completely withdrawing until midnight.

Oakland police prepared by boarding up their windows—from the inside.

Meanwhile, energized by the proposed general strike, countless new participants were flowing into Occupy Oakland. Many of them had not previously been exposed to the radical politics of those who had been involved in it since the beginning. Nonetheless, according to one member of the Industrial Workers of the World,

The General Assembly passed several key motions leading up to the General Strike—a motion supporting autonomous actions that occupied buildings for the purpose of expropriating them, a motion that reprisal pickets would be sent out where requested against schools and businesses that disciplined their students or workers for participating in the general strike, and that health and safety pickets would be sent out early where requested, so that workers would have a picket line to refuse to cross…

By Tuesday, the community colleges had large, public walkouts planned, most instructors had cancelled classes, and it all just seemed to arise out of the air.

Oscar Grant plaza on November 2, 2011.

On November 2, many longshore workers called out of work in the morning, leaving the port running at a diminished capacity. Students and teachers from Berkeley and Laney College marched downtown to join the strike after serving a symbolic eviction notice at Oakland Unified School District headquarters. The Men’s Wearhouse beside the plaza displayed a sign in its window saying “We stand with the 99%. Closed Wednesday, Nov. 2.” The marquee of the Grand Lake Theater read “We proudly support the Occupy Wall Street movement—closed Wednesday in support of the strike.”

Massive numbers of people gathered at Oscar Grant Plaza. According to the authors of “The Rise and Fall of the Oakland Commune,”

People gathered in the early morning under a giant banner, stretched across the central intersection in downtown, reading “Death to Capitalism.” From there, the crowds quickly fanned out across the center of the city, shutting down businesses that had refused to close for the day. The camp at the plaza became a crowded anti-capitalist carnival offering music and speeches from three different stages.

A participant in one of the flying pickets described their experience shutting down a café that had refused to close:

We began loudly shouting slogans like “Shut it down!” “General Strike!” and “Let them strike, it’s their right!” After we noisily created havoc and prevented the café from operating, someone negotiated with the boss and he agreed to close, let the workers leave, and pay them for a full day’s wages—even though they had not even been there half a shift. There were about 15 people working there, with about five Latino guys baking and cooking in the visible kitchen and the rest were young Black and white women and men working the counter and serving food.

Most of the workers were excited at our action, especially the ones who knew some of the Wobblies, but they had to be discrete in front of management. There was some confusion, at least until management disappeared from the windows, but once that happened the workers were all smiles and talked to us through the glass doors. We asked if we should stay or leave, and the enthusiastic response was “Stay!” …The same worker who told us to stay later said through the glass “You did it! You shut it down!” and gave one of the Wobblies a fist bump through the glass door. We stayed until all the workers had left the café, hoping that some of them would make it to the area around Oscar Grant Plaza to join the strike.

While we were waiting for the workers to leave, a couple of potential customers complained that we were “attacking a small local business.”

This narrative, like the events at the port, illustrates the extent to which this kind of “strike from outside the workplace” could be misunderstood or misrepresented as anti-worker. In fact, in 1946, it had been the Teamsters who had shut down restaurants in downtown Oakland, also acting from outside the workplace.

At 2 pm, at the intersection of Broadway and Telegraph beside the former site of Kahn’s, an anti-capitalist march that had been announced autonomously outside the consensus process of the Occupy assemblies gathered behind banners proclaiming “If we cannot live, we will not work—general strike!” and “This is class war.” Many participants sported black flags, motorcycle helmets, masks, matching black clothing, and shields painted to resemble the covers of books. These shields had first appeared during the Anticuts marches of the preceding summer, inspired by similar shields in Italy.

Led by a black bloc of hundreds, the march visited Chase Bank, the Bank of America at the Kaiser Center, the Wells Fargo at 12th and Broadway, Whole Foods—the management of which had refused to give workers the day off—and the University of California Office of the President, leaving a trail of graffiti and broken windows in its wake. One participant spray-painted “1946” across a cracked Bank of America window. This was a return to the tactics that anarchists and others had employed in the riots responding to the murder of Oscar Grant—and before that, most famously, during the mobilization against the summit of the World Trade Organization in Seattle. In addition to forcibly shutting down the targets, these tactics expressed uncompromising opposition to capitalism itself—establishing a confrontational pole in the distinctly heterogeneous Occupy movement. In effect, the participants were counterposing a rival memetic gesture to the assembly and occupation that had characterized Occupy up to that point.

“A large canister of paint was used to write the word “STRIKE” across the front windows. As the painters ran back toward the crowd some of those in the crowd decided these people needed to be tackled and knocked to the ground. Eventually, the scuffle grew to include the painters, the tacklers and the people who broke the painters free and allowed them to run into the crowd for safety.” –Bruce Valde in the December 2011 issue of the Industrial Worker.

Some witnesses disapproved; others charged that vandalism would discredit the movement. Debates about “violence” were rampant in the United States at that time, including in the Bay Area, peaking with Chris Hedges’ notorious text “The Cancer in Occupy.” It was only later, between the rebellion in Ferguson in 2014 and the first year of Trump’s presidency, that large numbers of people began to accept the need—at least in certain circumstances—for tactics that many had previously delegitimized as “violent.”

At 4 pm, thousands began to gather at 14th and Broadway to march to the Port of Oakland. According to one eyewitness,

Two marches would leave for the port, at 4 and 5 pm, the first, from reliable estimates, consisting of at least 10,000 people, the second consisting of 15,000-20,000 people. Plus many more people went to the port from elsewhere. The best estimates I have seen for the numbers at the port were 35,000-50,000, which I can easily believe.

According to another eyewitness,

As we got to the intersection at the Port where there is a traffic signal at the entrance to the APL terminal, I marveled at the trucks idled six abreast in the midst of the human swarm. I wondered what the troqueros thought about the shutdown, so I asked the first two I saw standing next to their trucks. I began by apologizing for preventing them from working. They immediately responded by rejecting my apology, saying “We’re part of this and we’re happy it’s happening.” Their only disappointment was that they thought the strike would happen in the morning.

According to Stephen Coles, “After 8 pm, there was some confusion among our crowd picketing the APL Gate about whether we had successfully blocked the full shift. Amid the arguing, this man stepped forward and said he was with the Longshore Union. He confirmed that the strike was successful and workers were not able to cross the lines. Some in the skeptical crowd demanded his ID as we were getting mixed messages from Twitter and other sources. He supplied it: Craig Merrilees, Communications Director for the International Longshore and Warehouse Union. He went on to say the workers were grateful to Occupy marchers for facilitating the picket line and then answered questions about arbitration from folks in the crowd around him.” This testimony is interesting because the following month, Craig Merrilees took an outspoken role in denouncing Occupy in the corporate media.

Finally, after night fell, hundreds of people occupied the Traveler’s Aid building a few blocks from Oscar Grant Plaza. Long empty, it had previously housed a nonprofit serving the homeless. In anticipation of a police raid, defenders built a barricade at 16th and Broadway to defend the area—though when they lit it ablaze, conflicts about “violence” broke out with renewed vigor. Finally, at midnight, the police, who had been absent all day, appeared in considerable force and attacked, recapturing the Traveler’s Aid building and provoking a night of rioting during which many of the businesses and city offices around the plaza were damaged, including a police substation.

Scenes from Oakland on November 2, 2011.

And then it was over. Having called for a big day of action, the movement went into a refractory period. It took some participants months to realize that November 2 had been the high point of Occupy.

Debates followed about the legitimacy of some of the tactics that anarchists had employed. Although the general assembly had passed a motion supporting autonomous building occupations, some still objected to the occupation of the Traveler’s Aid building; others were angry about the anti-capitalist march that had visited Whole Foods. As one participant observed, however, “Far more people participated in the Oakland General Strike than have ever attended a General Assembly.” Discussions about direct democracy, consensus process, and self-determination continued for years after Occupy.

On November 10, a man was fatally shot beside the encampment in Oscar Grant Plaza, underscoring the severity of the challenges that Occupy Oakland had taken on in attempting to create a commons in the midst of poverty and desperation. Early on November 14, the police evicted the camp again, this time permanently.

Nonetheless, some elements of Occupy Oakland were determined to continue developing a model for a 21st-century strike. In “Blockading the Port Is Only the First of Many Last Resorts,” published on December 7, some participants argued that it was essential to understand how the economy had changed since 1946:

This is why the general strike on November 2 appeared as it did, not as the voluntary withdrawal of labor from large factories and the like (where so few of us work), but rather as masses of people who work in unorganized workplaces, who are unemployed or underemployed or precarious in one way or another, converging on the chokepoints of capital flow. Where workers in large workplaces—the ports, for instance—did withdraw their labor, this occurred after the fact of an intervention by an extrinsic proletariat. In such a situation, the flying picket, originally developed as a secondary instrument of solidarity, becomes the primary mechanism of the strike. If postindustrial capital focuses on the seaways and highways, the streets and the mall, focuses on accelerating and volatilizing its networked flows, then its antagonists will also need to be mobile and multiple… mobile blockades are the technique for an age and place in which production has been offshored, an age in which most of us work, if we work at all, in small and unorganized workplaces devoted to the transport, distribution, administration, and sale of goods produced elsewhere.

As participants in Occupy Oakland began to organize towards another port shutdown, scheduled for December 12 and intended to encompass the entire West Coast, union bureaucrats and capitalist media outlets took advantage of the vulnerabilities of the model of strike as “intervention by an extrinsic proletariat” to sow dissension. The fact that ILWU members had to claim to be endangered in order to stop work—and had to claim to oppose the strike in order to avoid legal consequences—offered a convenient wedge.

“Occupy Oakland plans West Coast port shutdown, but port workers don’t support it,” proclaimed the Washington Post on December 5.

One’s perspective on the general strike of 2011 depended considerably on whether one was positioned within it…

…or outside of it.

“The ILWU International officers in San Francisco are claiming to have nothing to do with the December 12 action and even oppose it,” wrote the former Communications Director of the ILWU on December 8. “Officially, they must distance themselves from the action call to protect themselves from being sued by the PMA [Pacific Maritime Association] for the damages of the action. But they are going beyond the legally required disclaimers.”

After the blockades of December 12, which were more or less successful in the Bay but drew considerably fewer participants than the November 2 general strike, the New York Times accused Occupy Oakland of “co-opting the unions’ cause instead of working with them.” ILWU communications director Craig Merrilees denied that the ILWU tacitly approved of the strike, charging that Occupy organizers had been “very disrespectful of the democratic decision-making process in the union and deliberately went around that process to call their own action without consulting workers.”

“Their actions further alienate the movement from average American workers,” Forbes crowed.

Hostile press like this was inevitable. Even if the entire conflict had played out within the ILWU without any “outside agitators” to blame, corporate media would have published negative coverage of any faction promoting tactics that could exert significant leverage on employers. But bad press was not the chief obstacle facing those who sought to continue developing this model for a 21st-century strike.

The real problem was that a strategy based on precarious activists shutting down unionized workplaces from outside failed to bridge the gap between the divergent needs of the unionized employees and the precarious blockaders. If the goal was to shut down the economy as a generalized pressure tactic on behalf of the unemployed and precarious, it was not clear what the union members might stand to gain from this; many ILWU members earned comfortable salaries and had job security that was not worth risking for the sake of what some considered utopian or nihilistic adventurism. (“We have jobs and families,” said a random truck driver the Associated Press found to condemn the Occupy protesters; “Most of them don’t.”) If the goal was only to defend the bargaining rights of the ILWU, it was not clear what the precarious blockaders might stand to gain from taking considerable risks to preserve the security of workers who occupied a stabler position in the economy.

The ILWU leadership had no intention of being associated with blockades that could result in fines and other penalties, and they were determined not to cede control of the ports to a grassroots movement. In this context, even when rank-and-file union organizers attempted to organize a work stoppage—the chief form of leverage a union can exert—they had to do so from outside the workplace, defying the representatives of the union, as if they were themselves nihilistic adventurists. Calls from all sides to center the unions in actions at the ports only intensified this paradox.

Even in the best case, centering the unions—whether that was understood as the official leadership or as radical currents within the rank and file—meant deferring to people who were not necessarily invested in the fortunes of the Occupy movement or attuned to the strategic needs of the blockaders. It bogged down the organizing in internal debates within the group that had the most to lose from escalation, and shifted the objectives towards defending the jurisdiction of the official union structures rather than building new fighting formations to defend everyone impacted by capitalism. This produced diminishing returns as the movement itself melted away from one mobilization to the next.

A repurposed street sign in Oakland on the evening of November 2, 2011: “No work ahead.”

Jack Heyman and others did their best to legitimize the port blockades. Longtime radical labor organizers grappled with the questions that had come up in the blockades. And there was an opportunity to try again: some Occupy organizers were coordinating with an ILWU local in Longview, Washington, where the multinational corporation EGT was maneuvering to break the union. Hoping to show that Occupy could be real allies to unionized workers, they called for a regional convergence to block a ship that was scheduled to dock at the EGT facilities in that port.

Occupy Portland and Occupy Seattle organized planning meetings on January 5 and 6. At the first one, in Portland, the ILWU leadership made it clear that they would do everything in their power to hamstring the mobilization. According to a subsequent account, the president of one ILWU local seized the platform to read a letter from the president of the ILWU “calling on ILWU members who might participate in the convergence to be sure to keep their actions within the confines set by Taft-Hartley and to avoid working with Occupy.”

On January 6, 2012, over 200 people gathered at a labor solidarity forum called by Occupy Seattle to support Longview ILWU Local 21 in its battle against EGT. Supporters of the ILWU leadership from the Seattle, Tacoma and Portland ILWU locals disrupted the meeting—first verbally, then physically.

January 6: a meeting called for by Occupy Seattle to support ILWU strikers descends into chaos. Fighting unions means fighting within the unions. It always has.

In the end, according to one account,

The bureaucrats at the top of the ILWU outmaneuvered the planned blockade of the scab ship in Longview, and all plans for the convergence imploded. Occupy caravans had been organized from Oakland, Portland, Seattle, and elsewhere, while the federal government announced it would defend the scab ship with a Coast Guard cutter. Comrades from across the West Coast were just waiting for word from those working directly with the Longview Longshoremen to initiate a confrontational showdown. But in their determination to reorient Occupy towards labor activism, the tendency that had coalesced during the November 2 port blockade constructed a framework that was completely disconnected from the streets and plazas from which they had emerged. With every step from the November 2 strike through the December West Coast port blockade and towards Longview, these actions ceased to be participatory disruptions in the international flows of capital as a projection of the occupation’s power beyond the plaza. Instead, they became solidarity actions, organized only with supporting the union in mind. There was naïve talk about the actions sparking a wildcat strike in the ports, or prying the union away from the bureaucrats who were eager to defuse the conflict and cooperate with EGT. But none of this came close to materializing.

In the end, the labor solidarity tendency within Occupy Oakland and the handful of radical Longshoremen allies were no match for the political machinations of those at the top of the ILWU, who coerced the rank and file of Longview to accept a compromise with EGT that kept them on the job while stripping them of many benefits and their job security.

Radical elements of the ILWU described these events differently in a press release crediting the Occupy movement as a crucial element in the settlement with EGT. “It wasn’t until rank and file and Occupy planned a mass convergence to blockade the ship that EGT suddenly had the impetus to negotiate,” stated a sympathetic officer of ILWU local in the Bay Area. “Labor can no longer win victories against the employers without the community. It must include a broad-based movement. The strategy and tactics employed by the Occupy movement in conjunction with rank-and-file ILWU members confirm that the past militant traditions of the ILWU are still effective against the employers today.”

Even if this was a victory for the ILWU—which others denied—it did not help the Occupy movement to maintain momentum. They never repeated the port blockades of November and December. Efforts to coordinate with workers to blockade the Golden Gate Bridge for May Day 2012 fell through when, once again, the unions called off the action at the last minute. Though the blockaders’ risk tolerance may have given organized labor a small advantage at the negotiating table, putting union leadership in the driver’s seat of the entire movement drove it into the ground. In the end, the most vibrant events of May Day 2012 in the Bay as well as Los Angeles and Seattle drew more from the anti-capitalist march of November 2 than they did from the blockading of the port. Interrupting the economy from outside—without coordinating with union representatives or making demands—had proved more viable.

Looking back a year later, participants in the blockades argued that Occupy protesters should have shut down the ports themselves through direct action rather than focusing on loopholes in the ILWU contract. One organizer suggested that participants in Occupy were only able to offer meaningful solidarity to rank-and-file workers because they defied the union leadership and organized autonomously from it. Even Jacobin magazine, the executive director of which had willfully sought to discredit participants in Occupy who were skeptical of unions (disingenuously alleging that they believed that “‘building “communes,’ rather than confronting capital, should be the movement’s main mission”), detailed how the ILWU leadership had played a fundamentally reactionary role throughout the events.

Diversity of tactics? A demonstrator meditates while others set up burning barricades in the background: downtown Oakland on the evening of November 2, 2011.

Back in December 2011, the authors of “Blockading the Port Is Only the First of Many Last Resorts” had already concluded that it was blockaders and rioters, not unions, who represented the future of labor resistance:

In the present instance, the initiative is coming from outside the port and from outside the workers’ movement as such, even though it involves workers and unions. For the most part, the initiative here has come from a motley band of people who work in non-unionized workplaces, or (for good reason) hate their unions, or work part-time or have no jobs at all…

The coming intensification of struggles both inside and outside the workplace will find no success in attempting to revitalize the moribund unions. Workers will need to participate in the same kinds of direct actions—occupations, blockades, sabotage—that have proven the highlights of the Occupy movement in the Bay Area. When tens of thousands of people marched to the port of Oakland on November 2nd in order to shut it down, by and large they did not do it to defend the jurisdiction of the ILWU, or to take a stand against union-busting (most people were, it appears, ignorant of these contexts). They did it because they hate the present-day economy, because they hate capitalism, and because the ports are one of the most obvious linkages in the web of misery in which we are all caught.

The port blockade in Oakland: sunset on November 2, 2011.

Conclusion: The Takeaway

To repeat the words of the ILWU officer: “Labor can no longer win victories against the employers without the community. It must include a broad-based movement.” Even if you wish to focus on labor organizing alone, the only way to give it teeth is to organize with people outside of specific workplaces, without relying on union bureaucracy. Those who attempt to reenact a sanitized version of the strikes of 1946 without understanding what made the general strike of 2011 effective will not get far.

What would a modern-day general strike look like? It would involve a broad range of precarious workers, unemployed people, and other rebels taking disruptive action to shut down the economy from outside. However the strike might begin, it would have to proliferate horizontally, spreading beyond any single demographic as a contagious rebellion exceeding the control of any organization. It would entail targeting the choke points of the economy—physical locations like ports, highways, and distribution centers as well as online venues and other forms of infrastructure, not to mention the workplaces, schools, neighborhoods, and prisons in which most of us spend most of our lives. It would necessitate defying politicians, union representatives, community leaders, and everyone who defends their legitimacy. It would be controversial. To persist, it would require seizing and redistributing resources. Many of these actions would take place within workplaces, but to center the agency of official unions or other organizations that have legal standing under capitalism would be to ensure defeat in advance.

As capitalism renders more and more people precarious or redundant, it will be harder and harder to fight from recognized positions of legitimacy within the system such as “workers” or “students.” Last year’s students fighting tuition hikes are this year’s dropouts; last year’s workers fighting job cuts are this year’s unemployed. We have to legitimize fighting from outside, establishing a new narrative of struggle.

-Nightmares of Capitalism, Pipe Dreams of Democracy: The World Struggles to Wake, 2010-2011

Who is more entitled to occupy a school than those who can’t afford to attend it? Who is more entitled to sabotage the economy than those for whom there are no jobs?

But the general strike of 2011 also hit a wall. There hasn’t been another since. How could we get past that impasse? To answer that question, we have to look at what happened after the general strike of 2011.

A demonstrator paints “Strike” on the façade of the Whole Foods in downtown Oakland on November 2, 2011.

The Legacy of Occupy Oakland: The Afterlife of a Strategy

The assembly; the occupation; the blockade; the riot. Confronting the declining leverage of unions and labor organizing in a changing economy, Occupy Oakland experimented with all four of these, in turn.

In 2012, at the conclusion of the Occupy movement, if you had chosen participants at random and asked them which of those four models would be most widely adopted a decade later, they probably would have guessed that assemblies would become the most widespread, whereas rioting would remain the most marginal and extreme.

What actually happened is surprising.

Overseas, in Spain, where the immediate predecessor of the Occupy movement had appeared in the plazas of Madrid and Barcelona, people confronted the same questions in 2012 and arrived at some of the same answers. In Barcelona, during the nationwide general strike of March 29, 2012, many of the participants set out to shut down the economy from outside, using an array of tactics including roving pickets, blockading, and rioting fiercer than anything seen in the Bay Area in 2011. Striking students in Québec arrived at more or less the same strategy that same spring—crucially, with the assistance of non-student supporters. We can trace the circulation of these tactics around the world over the following years—from Turkey to Brazil, from France to Hong Kong, from Ecuador to Chile and Colombia. All of these upheavals offer useful reference points about how to disrupt the economy from outside the workplace.

In the United States, the breakaway march in Oakland on March 4, 2010 and the port blockades during the general strike of 2011 foreshadowed the highway blockades that spread around the country in 2014, inspired by the revolt in Ferguson. This movement improved on Occupy in many ways, centering the agency of those most impacted by white supremacy and police violence. Later, at the opening of the Trump era, thousands of people blockaded airports, fulfilling a proposal that had seemed outlandish in 2012.

“It’s a man’s world: let’s fuck it up.” A banner at the blockade of the port in Oakland on November 2, 2011.

As the intensity of these confrontations picked up, however, horizontal, open assemblies largely fell by the wayside. People overcorrected for the most maddening aspects of the Occupy assemblies (the centrality of white and male voices, the tendency for proposals to bog down in consensus process, the lack of meaningful affinity) by shifting to entirely decentralized and informal frameworks or else by adopting a cadre organizing model tying legitimacy to identity. Anarchists withdrew to affinity groups and collectives, other activists to organizations and parties. The social body that had gathered at the occupations fractured into invite-only Signal threads, socialist groupuscules, and the Bernie Sanders campaign.

Afterwards, while social movements picked up steam around the world, efforts to connect workplace organizing with confrontational street activity did not gain much momentum.2 The tactics that some activists in Oakland had experimented with in order to update the labor movement for the 21st century became associated almost exclusively with efforts to grapple with the capitalist landscape outside the workplace: fighting fascists, opposing deportations, imposing consequences for police murders.

This culminated in the generalized uprising that broke out in May 2020 in response to the murder of George Floyd, facilitated by the fact that the first wave of COVID-19 had already imposed an almost total work stoppage on society. (Talk about a general strike introduced from outside the workplace!) The confrontational tactics that were essential to catalyzing this uprising were precisely the same tactics that had been most controversial during Occupy.

In the wake of a high point of activity like the George Floyd uprising, activists often become disoriented and dispirited. Because the bar for what counts as a victory has been raised so high, projects or goals that felt worthwhile before the uprising can seem meaningless. Looking for a new way forward, some people who participated in defeating police departments and shutting down cities in 2020 have turned their attention to labor organizing without thinking about how the experiences of summer 2020 might inform it—and without any inkling that the tactics they employed that summer were descended, in part, from an effort to reimagine labor resistance for the 21st century.

If blockading, rioting, black bloc tactics, the establishment of “cop-free zones,” and other tactics from 2011 have spread far and wide while labor organizing models have remained at an impasse, this should inform our strategizing. Of course, just because a particular tactic thrives in our current context does not mean that it will suffice to solve the problems we face. After the 2020 revolt, it’s a good idea to seek an even broader basis for collective struggle—and in theory, labor organizing could offer this.

So what is missing from the toolset that reaches us, indirectly and incompletely, from the experiments of Occupy Oakland?

A decade ago, many anarchists considered it their top priority to escalate social conflict. In retrospect, those who fantasized about “social rupture” in 2009 were like the Futurists of 1909 who published a manifesto demanding more aggression, speed, and war immediately before the outbreak of World War I. Today, we have conflicts and ruptures aplenty; increasing atomization and polarization are the only things we can count on. What is not guaranteed is that we will be able to build long-term connections on a large enough scale to collectively produce a shared vision of how to improve our lives.

Demonstrators at the port blockade in Oakland on November 2, 2011.

Despite the role that their leadership played in suppressing the general strike, the unions of the 1940s also offered an indispensable venue for rank-and-file workers to connect with each other in order to build a culture of solidarity. Without those unions, the general strike of 1946 would never have occurred in the first place. Likewise, in place of the unions of the 1940s, Occupy Oakland had the encampment and the assembly: these served as spaces of encounter, enabling a broad range of people from many different walks of life to rapidly build new social ties and shared visions. The “Oakland Commune” emerged in this space, a semi-mythological collectivity representing the dream of sharing and fighting together. In reality, the Occupy Oakland encampment was often a very challenging environment, to say the least; afterwards, some participants suggested that, like the unions of 1946, it was both essential to the movement and ultimately implicated in its demise. But this is an argument to improve on the model it offered, rather than trying to do without a space of broad connection.

As our relations become ever more atomized, disposable, volatile, and fraught, mirroring the society we live in and the economy that drives it, the absence of spaces for meaningful ongoing connection is one of the greatest challenges facing us. If we are to apply the lessons of 2011 to today’s labor struggles—bringing together the employed, the precariously employed, and the unemployed in a common struggle that challenges capitalism as a whole, rather than seeking to defend the status of small segments of the working class—we will need new spaces of encounter in which to build collectivity.

What model could connect us today the way that the unions connected people in 1946 and the Occupy assemblies connected people in 2011?

Friends, we leave you with this question.

“Revolt—for a life worth living.” A banner in downtown Oakland on the night of November 2, 2011.

Forget about going back to the old days—there can be no more peace treaties between classes when even governments are scrambling to keep up with the accelerating effects of capitalism. Forget about fighting to preserve your economic role and privileges—the only hope is to legitimize common resistance from outside them, against them. Forget about strategies based on incremental victories, radicalizing our demands as people build up a taste for winning—today it’s easier to topple governments than to reform them. We have to popularize new ways of fighting that create social bodies outside all capitalist roles, that can one day put an end to capitalism itself.

Further Reading

A few points of departure to learn more about the two general strikes.

Oakland 1946

- The Oakland General Strike, Richard Boyden

- Strike!, Jeremy Brecher

- 1946: The Oakland General Strike, Stan Weir

- Stan Weir’s oral history of the 1946 Oakland general strike

- Unions And The State: Relevant Lessons From 1940s Anarchists

Oakland 2011

- The Anti-Capitalist March and the Black Bloc

- Blockading the Port is Only The First of Many Last Resorts

- A Letter from Some Friends in Oakland Regarding the January 28th Events

- A Message to the Partisans, in Advance of the General Strike

- Notes on Oakland 2011, by Asad Haider

- The Oakland Commune, by Aaron Bady

- The Oakland General Strike, the Days before, the Days after

- Oakland’s Third Attempt at a General Strike

- Occupy Oakland Is Dead; Long Live the Oakland Commune

- On the Ground at the Oakland General Strike

- One Year After the West Coast Port Shutdown

- The Rise and Fall of the Oakland Commune

- Square and Circle: The Logic of Occupy, by Jasper Bernes

- Struggles on the Waterfront, Black Orchid Collective

- Unions that Used to Strike

- What the Oakland Commune Did

-

For the sake of brevity, in this analysis, we pass over over the nationwide “Day without an Immigrant” strike of May 1, 2006, one of few other contenders in the category of 21st-century general strike. It’s worth noting that the “Day without an Immigrant” strike was initiated by one of the most precarious demographics in the United States—and that the chief objective was not to negotiate their salaries or workplace conditions, but to press the government not to render them even more precarious. ↩

-

The popularity of “anti-work” politics today is the logical consequence of seventy-five years of reversals in the labor movement. It represents a sober (if chiefly instinctive) assessment of the prospects for old-fashioned labor organizing. ↩