In the following interview, two longtime anarcho-punks recount the reemergence of anarchism in Brazil after the end of the military dictatorship, trace the fortunes of social movements through the rise and fall of the left Workers Party government, and describe the situation for Indigenous peoples and Indigenous solidarity efforts under the far-right Bolsonaro regime today.

Andreza and Josimas have been involved in anarchism and activism for several decades—playing in bands, organizing events, and releasing records and zines and books. Josimas was one of the people who founded Germinal (2000) and Andreza participated in founding Espaço Impróprio (2003), two important autonomous anarchist collectives in São Paulo. Josimas has played in the bands Execradores, Metropolixo, Clangor, Diskontroll, and Amor, protesto e ódio. Andreza has played in Skirt, One Day Kills, Out of Season, and Retórica. In addition, they have played together in Você Tem que Desistir and TuNa.

Their current projects include Semente Negra (“Black Seed”), an ecological project in the Atlantic rainforest and the location of Cultive Resistência (“Cultivate Resistance”), a collective promoting do-it-yourself culture, permaculture, anarchism, punk, feminism, anti-racism, veganism, LGBTQIA+ issues, and Indigenous rights; No Gods No Masters, both a distribution and an annual festival that hosts anarchists, punks, and Indigenous people from all over the world; and Vivência na Aldeia, a nine-year-running Indigenous solidarity project.

Thanks very much to Karen for assisting with translation.

The entrance to Semente Negra, an ecological project in the Atlantic rainforest. “Starting here, we will be sharing space with many other living beings. Animals and plants interact and depend on each other. Take care! Do not destroy.”

In the 1980s, when anarcho-punk emerged in Brazil, what legacy remained from the earlier generations of Brazilian anarchism? How significant was that in the renaissance of anarchism in Brazil in the 1980s and 1990s?

The anarcho-punk movement in Brazil emerged in the late 1980s, as the result of a more active political consciousness within the punk movement in general. In Brazil, there had long existed several punk gangs that fought among themselves; this created the need for a sharper political awareness. In the mid-1980s, when Brazil was still ruled by a military dictatorship, some anarchist groups resumed their organizing and a few punks decided to get involved. There was the pro-COB (Confederação Operaria Brasileira) hub and Juventude Libertária (the first Brazilian Libertarian Youth group), in which one could find some punks already. However, when the Social Culture Center (Centro de Cultura Social) got back on its feet—a project over half a century old that had been persecuted and shut down under the military dictatorship—these young punks found themselves a reference point.

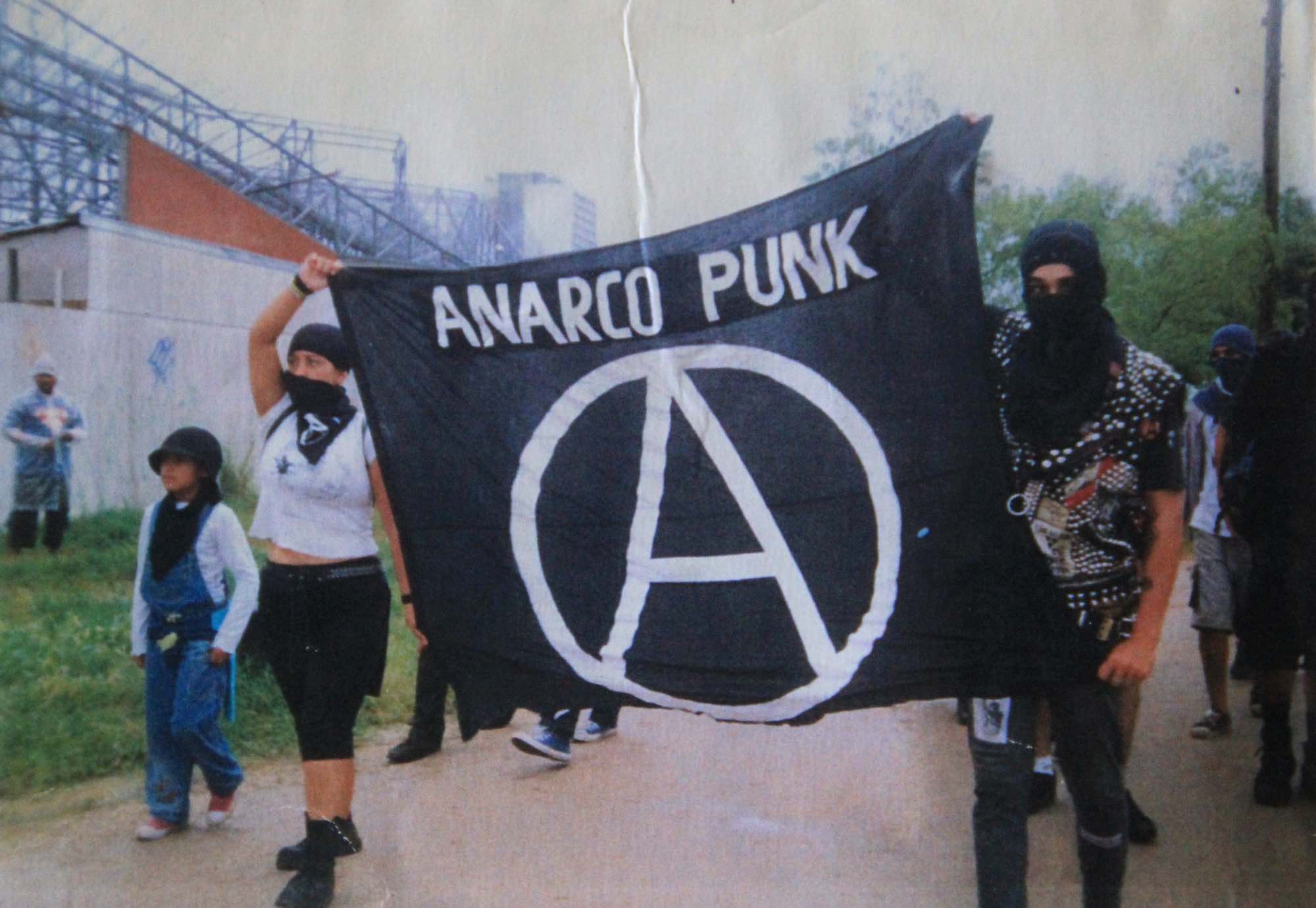

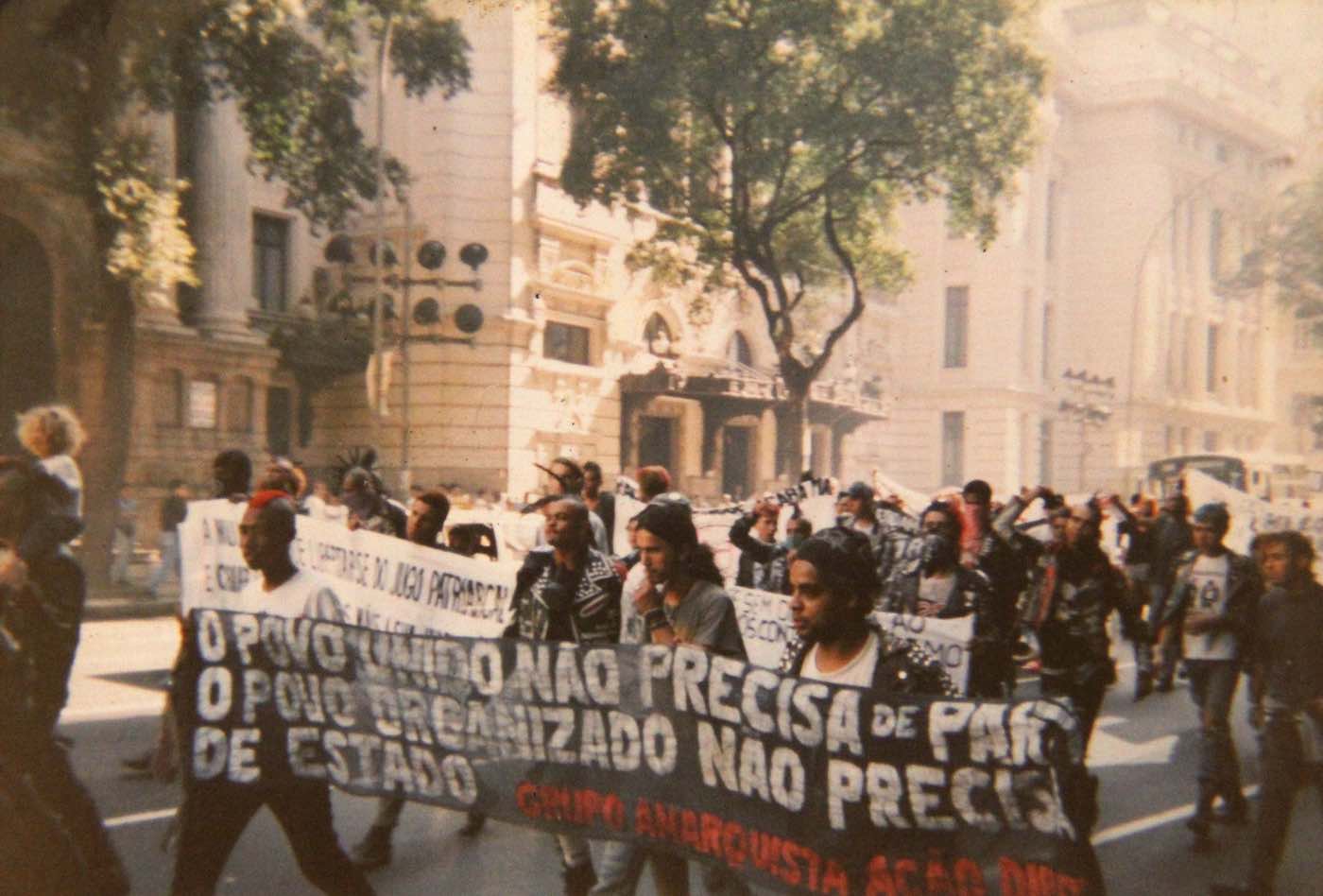

Against militarism—the anarcho-punk movement.

Anti-militarist punks in Belo Horizonte.

The older fellows from CCS reopened the project in 1985. They had a lot of willpower and organized several activities on political awareness and anarchist culture. They also assembled a library with a wide range of anarchist books and newspapers, which served as the basis for a powerful convergence between punk culture and anarchism.

The military dictatorship ended in 1985. When older anarchists returned to the streets, punks approached them; there were several discussions about these young folks from the urban outskirts with their weird clothes and hairstyles and loud music. Some of the older anarchists served as an inspiration—especially Jaime Cuberos (1926-1998), who saw punks as the new anarchists. They offered crucial sources of learning for a new generation that was looking for a social struggle that went beyond rebellion.

Two libertarian1 punk gatherings took place in Brazil in 1989 and 1990, bringing together punks who already identified with anarchism. In the early 1990s, the Anarcho-Punk Movement arose, especially in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. It soon spread to other cities as well, especially in the states in the northeast of Brazil—one of the poorest regions of the country. There was a radical need to organize collectively and federatively in the political scenario that arose after the military dictatorship. The social situation of people in the country was horrible; the monthly inflation rate reached 140%. In response, the youth called on people to organize and fight—and a considerable part of this youth was comprised of Brazilian punks.

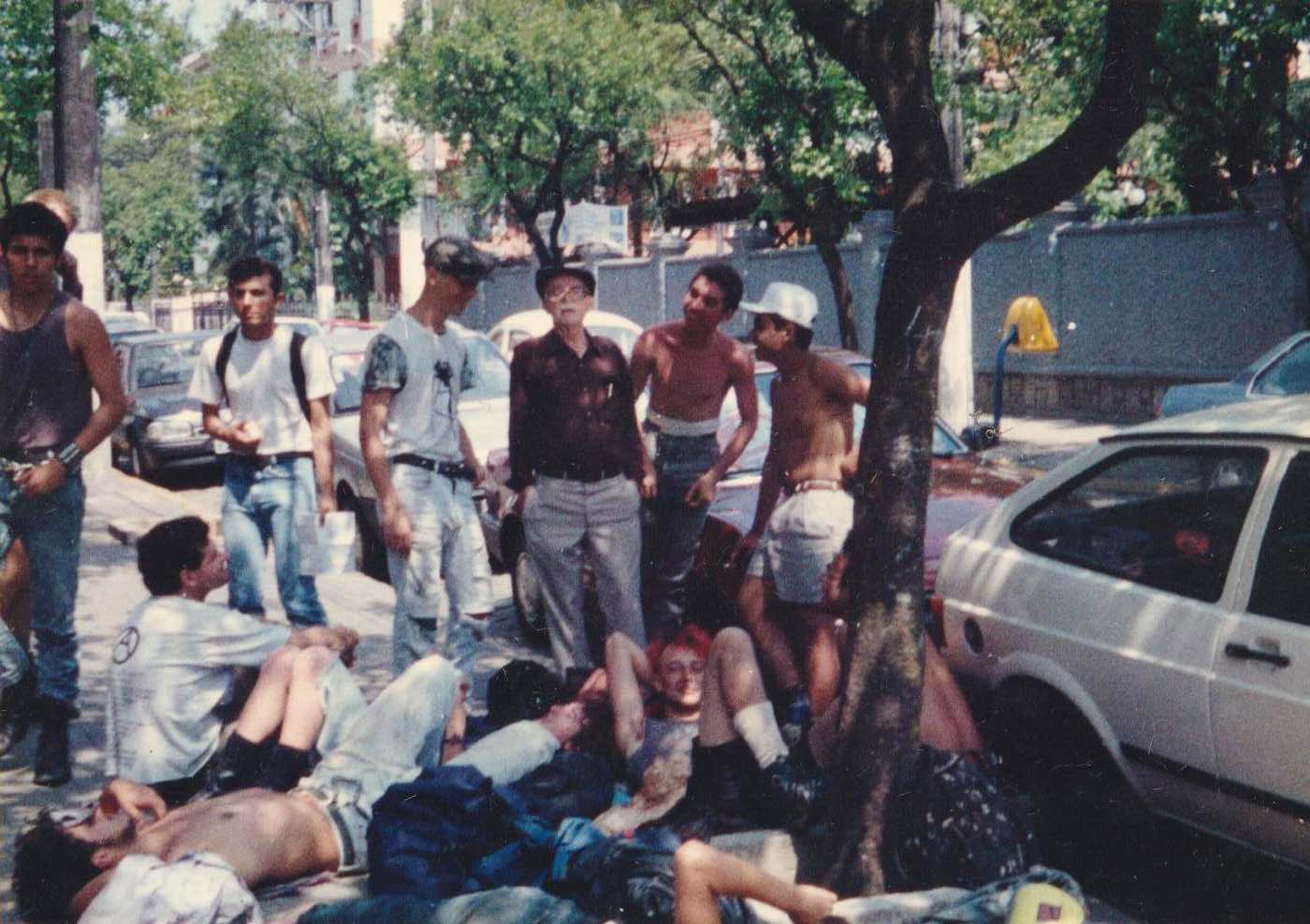

Intergenerational transmission: Santos, 1993.

Consequently, anarcho-punk collectives appeared in most of the big cities around Brazil, and also in several smaller cities. These collectives worked together to organize demonstrations, concerts, discussions, and study groups and to write articles. Many bands formed at this time, as well.

Some of these groups eventually got involved in other social struggles, including feminism, anti-racist struggles, and anti-fascist social groups.

It is important to say that in Brazil, anarcho-punk has always been a political definition, not a genre of music. In Brazil, anarcho-punk bands are bands formed by people who are involved in the anarchist movement and the punk underground.

Anarcho-punk congress, Rio de Janeiro, 1995.

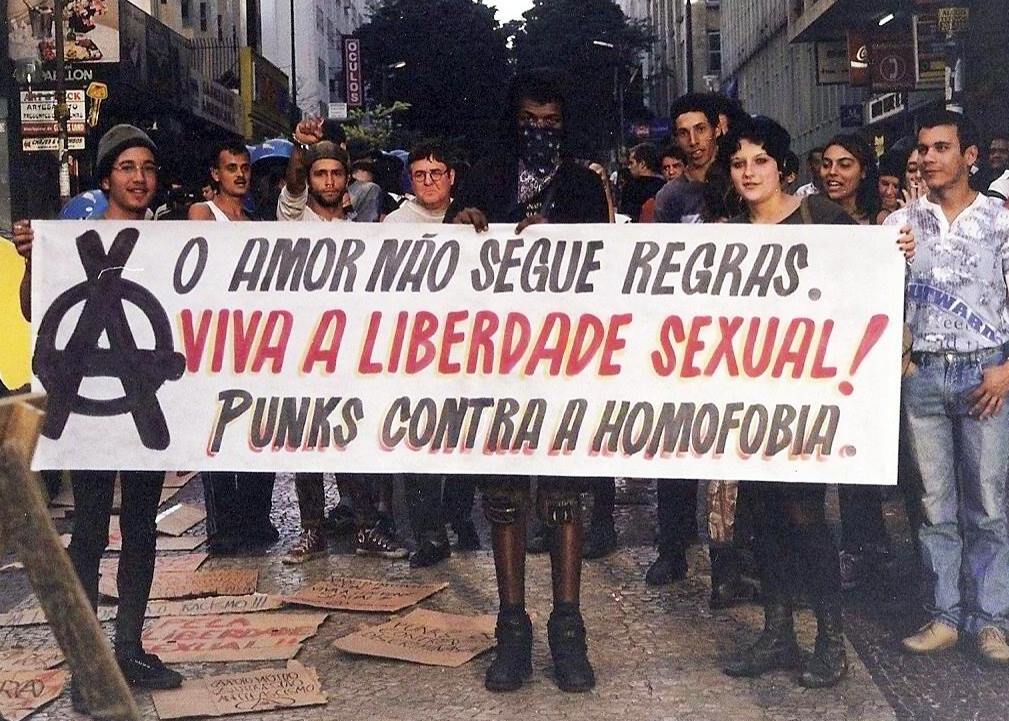

Anarchists and punks in Belo Horizonte in the 1990s: “Love doesn’t follow rules—Viva sexual liberty!—Punks against homophobia.”

Did punk take a different form in Brazil because of the ways that the racial and colonial context differs from Europe?

Yes, in Brazil, punk arose as part of a social opposition to the military dictatorship. In Brazil, over 60% of people are Black; punk arose in the urban outskirts, where this number represents 85% of the population. In a scenario in which young Black poor people had no hope of any improvement in their quality of life, there were no social or cultural programs supporting them, either. At the same time, there was often open violence as part of this oppression. Consequently, anarchist struggle and the struggle for survival were interlinked.

This scenario is less common in countries where people have a higher standard of living, as in Europe, for example. In Brazil, punk arose as a rebellious response to state oppression, as a struggle for survival as well as a cultural alternative. This is common in Latin America. These countries have been invaded and exploited; they are inhabited by the descendants of enslaved peoples. The social and economic disparities here are vast. In Brazil, young Black men living in some of the urban peripheries rarely reach 25 years old without being incarcerated or killed. This reality determines how we struggle as Latin Americans; it also illustrates the differences between Latin American and European countries. Many punks are descendants of either Indigenous or Afro-diasporic enslaved populations. Here, people are struggling to stay alive, above all.

May 1, 1995. Note the display with the portraits of the Haymarket martyrs from 1886, the origins of May Day as an anarchist holiday.

May 1, 1995.

The literature distribution table on May 1, 1995. “The first of May is a day of protest, not a party!”

How did punks and anarchists relate to the autonomous movements of the 1990s?

As the anarchist movement returned to the streets and anarchist political awareness arose within punk circles, there was a convergence between different social struggles evoking the need for working together with different groups.

When the MST (Movimento Sem Terra, the Landless Workers’ Movement) started to expand and to occupy farms, that was very inspiring. This was direct action against the injustice inflicted on a tremendous number of people who do not have access to land on which to live and produce their own food while a few people own entire states of unused farmland. At the same time, people involved in the MTST (Movimento dos Trabalhadores Sem Teto, the Homeless Workers’ Movement) occupied abandoned buildings in large cities to serve as homes for those living on the streets.

These two movements were inspiring for us because they were legitimately popular actions involving people who are deprived as a result of their history. Initially, we engaged with these movements through solidary actions, support, and participating in the front lines of demonstrations. Some anarcho-punks moved to MTST occupations and MST-occupied lands, becoming an effective part of these struggles.

In the 1990s, anarchists and anarcho-punks worked side by side with many struggles, both learning from them and teaching and supporting them. This included support groups for anti-militarist struggles (including conscientious objection), support groups for incarcerated populations, ACR (Anarchists Against Racism), and anti-capitalist groups… There was a feeling that rebels who were involved in struggle should be united.

“Against violence and war! End militarism!” A demonstration in Curitiba in the 1990s.

“Freedom for Mumia Abu-Jamal!” A demonstration in Curitiba in the 1990s.

In the early 2000s, the anti-globalization movement arose in Brazil. It had an anarchist basis, but it was also in line with several other growing struggles around the country. This organization brought together several anarchist fronts as well as other movements of social struggle. After several study groups, people formed People’s Global Action—a radical anti-capitalist movement that organized several demonstrations in Brazil. The participants experienced considerable police repression, but there was also a lot of strength on the rebel side.

Demonstration for International Women’s Day, March 8, São Paulo.

How did the election of (Workers’ Party presidential candidate Lula Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva) affect the political terrain in which you were organizing and the movements that you were participating in?

Before Lula was elected, we had been having several debates about our position regarding the election. We had been advertising the null vote since the “re-democratization” (the end of the dictatorship) and the first election. However, at that first election, in 1989, some anarchist and punk groups from the working class area had a tendency to vote for Lula, as it was an area where Lula used to live and where several union struggles also took place. In the following elections, support for Lula increased significantly among left movements including the MST and MTST as well as other popular groups. We were interconnected with several groups involved in social struggles, including some that supported Lula, which also included some anarchists. By this time, the anarcho-punk movement was no longer organized the way that it had been previously. Several collectives had ceased to exist and some of those people joined other diverse struggle groups.

In 2002, Lula was elected and there were high hopes that he would support popular social struggles in Brazil. Several social and collective struggle groups expected changes. There was a very long period of social stagnation in Brazil. Several groups discussed basic problems concerning single-issue struggles as a manner of addressing specific needs. Unfortunately, we feel that this weakened us a great deal when it came to collective struggle. To give just one example—during the PT (Workers’ Party) governments, we saw very few victories in Indigenous land demarcation, actually even fewer than before, though there had been high hopes that this would be different. It was as if we had hit pause in many fights.

“A good Nazi is a dead Nazi!” Punk anti-fascists in Belo Horizonte.

Anarcho-punks demonstrating in Belo Horizonte.

What role have social centers played in punk and anarchist organizing in Brazil?

The Centro de Cultura Social (Social Culture Center) has been one of the most important social centers in Brazil. They began in 1933 and have been active until today. They organize lectures, meetings every Saturday, and theater groups. They also have a huge historical collection. Several other social centers emerged from the union of anarchism and punk. In Salvador, in the northeast part of Brazil, the anarchist project Quilombo Cecilia united anarchism, punk, and Black struggles; the name is a reference to Colonia Cecilia [a Brazilian anarchist commune that existed in the 1890s]. In São Paulo, there was Comuna Goulai Poulé, an anarcho-punk cultural center; Centro de Cultural Social da Vila Dalva; Centro Cultural O Germinal; and Espaço Improprio, a social center that was active for eight years and united anarchism, punk, veganism, feminism, and queer politics and hosted several collectives. People squatted a few buildings in the 1990s, as well—some of which remain occupied today. In addition, several anarchist homes became social centers where people would meet to build projects, hold meetings, and share experiences.

These places have always served as resources for young people to gather, find anarchist material, and participate in political outreach events.

Capitalism and the huge social differences that exist in the country are significant problems that impact us. The history of these social centers is shaped by this reality, which has forced several social centers to close down due to the costs of maintaining these spaces.

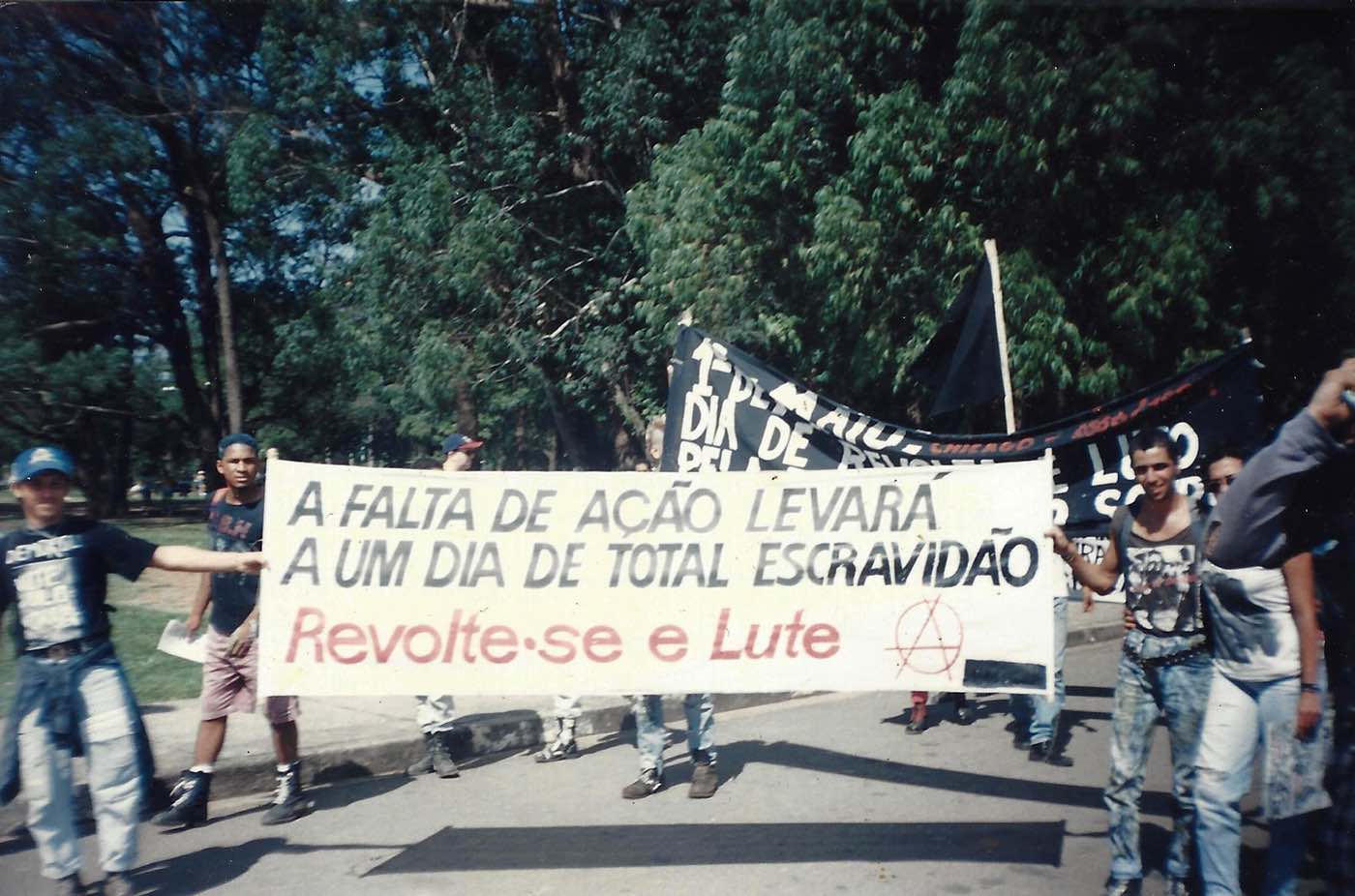

Anarcho-punks demonstrating in June 1995.

How did anarchist organizing and autonomous movements set the stage for the powerful movements of 2013 in Brazil?

After the Partido dos Trabalhadores (the PT, or Workers’ Party) took power, quality of life increased among parts of the Brazilian population and a few benefits and rights were achieved. However, the forms of social change that were most necessary had never been part of the PT plan, and this became obvious when PT candidate Dilma Rousseff was elected president after Lula. Most of what anarchists had warned about before the elections became clear to many people. Rebelliousness increased among different sectors of the society. Movements such as the MST and others that hadn’t organized demonstrations for years decided that it was time to show their dissatisfaction, concluding that they still had a lot to fight for. During the ensuing uprising involving the social movements that had been waiting for over ten years for what Lula had promised, the government focused on criminalizing demonstrators; this attitude caused the demonstrations to really explode. It started with the fight against the increase of the cost of bus fare. Soon, protests regarding many other necessities were incorporated into the demonstrations. The country burst into flames. Although there was no unity, people were eager for change.

At the same time, an ascendant part of the population that would soon become a strengthened middle class turned against the poor and those living in the urban outskirts. What took place seemed to be a movement to prevent those who were really badly off from getting out of the bad situation they had always lived in. It was something like the poor people against the poorer, and a right-wing atmosphere began to emerge at many demonstrations. Even though radical groups were divided into small affinity groups, they were linked together; demonstrations continued in 2013 and in 2014, before and during the 2014 World Cup.

We do not believe that we were really prepared for these demonstrations. Groups and people did what they could do with the tools they had. They managed to connect with each other little by little in an attempt to build a network. Perhaps we were better prepared before the PT took power, but the period of the PT government dismantled some of our connections and eroded some of our strategies. People seemed to be waiting to see what would happen—and they saw it. Looking back, we believe that we made the mistake of not creating an autonomous structure in opposition to the state, regardless of which party is in power.

Describe the festival you organize, No Gods No Masters fest.

The collective we are part of, Cultive Resistência, uses several tools for action. One of these tools is the press and distribution No Gods No Masters, which edits, publishes, and distributes books, zines, and records.

A band performing at Espaço Cultural Semente Negra, the Black Seed Cultural Center.

The idea of the festival emerged as we perceived the urgency of coming together in one place in order to discuss the issues we write about in the zines and books, the issues that impact people’s lives. For three days, music, lectures, workshops, films, exhibitions, and discussions take place in our house, Espaço Cultural Semente Negra, which is located in the forest in a small town, Peruíbe, in the state of São Paulo. Our proposal is to bring together different forms of resistance including anarchism, queer politics, feminism, veganism, Black and Indigenous struggles, punk, and other proposals relating to struggle.

Black anarchists have presented activities at the festival, bringing their different realities and expectations to this mixed collectivity.

There are several Indigenous communities where we live. We have developed a project for supporting these communities and we have worked with them since 2012. It has been very important to involve Indigenous people in the festival. They bring their culture, their way of seeing the world, their music, their experience with medicinal herbs, and their forms of resistance. These are people who exist as resistance all the time. They have no choice whether or not they can be resistance. If they stop resisting, they die.

A capoeira teacher at the No Gods No Masters festival at Espaço Cultural Semente Negra.

A graffiti workshop at the No Gods No Masters festival.

A silkscreening workshop at the No Gods No Masters festival.

How did the election of Bolsonaro change the political context for popular movements?

There were some pretty complicated processes during the 2018 presidential campaign. It was perhaps the most violent election we’ve ever seen. Some anarchists chose to vote for politicians running against Bolsonaro as a strategy to support women, Black people, and Indigenous people; others maintained the campaign for the null vote, which generated a very complex discussion within Brazilian anarchism.

After the election, there was a certain panic, as we experienced a wave of right-wing violence on the streets. This violence is still very strong, but we also saw a regrouping of social movements. Groups that had been organizing themselves in affinity groups opened up in order to join forces and build something stronger. Several strikes took place as well as many anti-fascist and anti-racist demonstrations. We believe that people have come to understand that it is necessary to support each other’s struggles rather than just fighting for a specific need.

The countryside around Espaço Cultural Semente Negra.

What is the situation for Indigenous people under Bolsonaro? How are Indigenous people organizing?

This may be one of the worst times since the arrival of Europeans in the Americas. When it comes to criminal actions against native peoples, the perpetrators are granted legitimacy and impunity. Indigenous lands have been invaded and attacked, forests have been set ablaze, Indigenous leaders have been murdered, Indigenous rights have been taken away, popular hatred against Indigenous people is being promoted. And all this is a plan organized by the Bolsonaro government.

At the end of 2019, Bolsonaro began the process of militarizing FUNAI [the Fundação Nacional do Índio, or National Indian Foundation], a public institution responsible for Indigenous land demarcation and addressing the needs of Indigenous peoples. Immediately, there were occupations in FUNAI buildings against this militarization. Here, in our region, 300 Indigenous people occupied the building and people fought against the militarization of FUNAI for 28 days. This also happened in other cities in Brazil. Unfortunately, the military took over the leadership positions at FUNAI and as a result, FUNAI has stopped supporting families and social projects that aim to support Indigenous communities. Consequently, the fight has become more intense but also more dangerous, especially in the Amazon and in states where there are massive cattle farms. Across Brazil, people are fighting for survival and it is important that we rebels stand by this resistance.

An indigenous demonstration at a Fundação Nacional do Índio (FUNAI) building against the repressive policies of the Bolsonaro regime.

Describe the solidarity work that you are involved in.

We use several tools of struggle and we aim for autonomy. One of these tools is permaculture: planning sustainable environments and using ecological techniques to build houses with soil and local material. In 2012, we were invited to support the new Indigenous communities that were being built in our region. The area had been previously dominated by a mining company that had expelled the Indigenous people from their own land and exploited its natural resources for over 50 years.

At first, we started by supporting the construction of houses in the communities. Then, over time, we got involved in helping to address several other needs relating to the families and their struggles.

Volunteers helping to construct houses in reclaimed Indigenous land adjacent to Espaço Cultural Semente Negra.

Our main role is to serve as a means of supporting the projects of the Indigenous communities. The idea is to build up community self-esteem, breaking down prejudice, holding joint events in order to bring the dreams of the community into reality, but especially, to stand together in resistance and struggle.

These families have been fighting for their land all their lives. They have been persecuted by the Jesuits, by farmers, by real estate speculators, by mining companies. Since the year 2000, the year that they were able to take over their land, they have been fighting to stay in this territory, while restoring their culture and their way of living.

We support them in their struggles; in the construction of their houses, community kitchens, vegetable farming areas, and ecological sanitation; in courses and workshops; and in their struggles against the state. All this is built through horizontal relations and our starting point is always the wishes of the community.

Anarcho-punks helping to construct houses in reclaimed Indigenous land adjacent to Espaço Cultural Semente Negra.

Are there other examples around Brazil of anarchists and Indigenous communities working together?

There are people who support this struggle and some anarchists whose grandparents are Indigenous have also sought to live within Indigenous communities and their struggles. There are also a few solidarity groups that work with different ethnic groups in several places in Brazil.

Now, with the pandemic, this has become more effective and there is a network federating anarchist groups that support Indigenous struggles. This is currently an ongoing process.

Punks at the No Gods No Masters festival at Espaço Cultural Semente Negra.

Participants in the No Gods No Masters festival.

What are some of the challenges in Indigenous solidarity work?

In Brazil, there are countless struggles and we need to be aware of many different things at once. There are groups that focus on specific issues, but we understand that it is important to support the largest possible number of struggles so that we don’t leave anyone behind. Due to the number of struggles and an economy in decay, supporting populations that live on the edge of misery or in absolute misery becomes a challenge, as they can no longer maintain their ways of living. The lives of Indigenous families are eternal struggles for survival and, most of the time, it is necessary to do everything based on solidarity and with scarce resources.

Lack of resources and the small number of people fighting on so many fronts are enormous challenges along with our struggle for survival. Embracing the Indigenous struggle, which is the most constant struggle in Brazil, means letting go of ourselves full time to minimize the impacts of occidental culture and capitalism on these families.

Are there common threads that connect your experiences in the anarcho-punk movement and Indigenous communities?

Yes, there are incredible connections that we have noticed over time, living close to the communities. The mutual support network, the assemblies, the importance of music as a tool for fighting, the relationship with education, consensus-based decision-making, traveling from one community to another, taking care of each other. All this is familiar to us from the punk traditions that we believe in and that we want to keep alive in our own lives.

The main difference, in our opinion, is their relationship with nature, with the planet. Our Indigenous comrades see themselves as a part of nature alongside all other animals and plants, while we, as the people of civilization, try to disconnect ourselves, creating crises inside and outside of ourselves.

“Here, there are no authorities but yourself.” No Gods No Masters festival at Espaço Cultural Semente Negra in 2019.

How can people support your projects and other important anarchist and Indigenous projects in Brazil?

We are focusing on three projects. Semente Negra, our social center, which is located in the middle of the Atlantic forest, is the place where we are working with permaculture as well as a silkscreen studio, a recording studio, our printing house, and our home. No Gods No Masters is our publisher and distribution for punk, anarchism, feminism, veganism, and other materials related to struggle. And Vivência na Aldeia is our solidarity project working with Indigenous communities.

Maintaining all these projects is laborious, but it has been part of our lives for many years. This is what we are and we put our energy into all of this. Sometimes we are forced to take smaller steps and choose what to prioritize because we don’t have the money for all the things we would like to do. We put special effort into all the things that can be accomplished without involving money. This has a very important meaning because it is the space where we can practice things in a more personal manner, through relationships of love and friendship. This is what we seek to build in all of our projects and with all the people we collaborate with.

During normal times, we try to raise money for the solidarity campaigns and for projects within Indigenous communities through the events we organize and the sale of T-shirts. All the activities themselves are done collaboratively with the communities. However, we are never able to raise enough due to the number of issues these communities face, the struggles they have to fight, and the dreams they aspire to fulfill.

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, we have created an online store to help sell handicrafts by our comrades in order to ensure that they will not have to leave their land to sell them and to keep families living and producing through their culture. Soon after, we helped start a campaign called Alimentação e Vida na Aldeia [“food and life in the village”], which aims at achieving food sovereignty for the eleven communities in the area, a total of approximately 500 Indigenous people. Unfortunately, as we said, this land is located in an area devastated by a mining company, so planting is still a big challenge. Therefore, the campaign aims to bring food and information to the communities.

We need to raise awareness about the reality of the social struggles in Brazil and the situation that Indigenous people face. We need to build support for a wide range of projects. Solidarity, struggle, and mutual support are our best weapons.

You can learn more about these projects through the websites:

-

In the United States, the word “libertarian” has been appropriated by those who only care about the freedom to profit at others’ expense and defend their ill-gotten gains. Everywhere else around the world, it means exactly what you would expect it to mean: anti-authoritarian. ↩