July 4 saw fiercely ungovernable demonstrations from Olympia to Atlanta. The following report from south Minneapolis describes a march that took place that evening, exploring the logic of autonomous organizing and concluding with a gallery chronicling the graffiti that the march left in its wake.

A.C.A.B.

Say it with me baby

Fuck the pigs

Like it’s Minnehaha and Lake Street

On the night of July 4, a small but rowdy crowd took to the streets of south Minneapolis to celebrate the the recent uprising and express support for those still facing charges from it. About forty people retraced a now-familiar route from George Floyd Square along Lake Street to the burned-out carcass of the Third Precinct, shooting off fireworks, burning American flags, and covering the area in fresh graffiti. Above all, the night affirmed the joy of the revolt—a joy born of thousands finding their power in acting collectively.

This celebration was organized autonomously. Autonomous organizing can be confusing for those more familiar with traditional protests choreographed by activists and “community organizers.” Instead of building a coalition of organizations to coordinate the event, networks of friends self-organized to set the stage for an open-ended evening. Rather than concentrating agency in a formally designated leadership, this approach invites all the participants to understand themselves as active contributors. In this case, several different people arrived with fireworks to set off; some handed fireworks out to others who wanted to join in on the fun. A few people got to light fireworks for the very first time!

Even without established leadership, there can still be planning. In contrast to a protest organized according to top-down logic, however, the plan can be loose enough to allow for spontaneity; in some cases, plans may not be openly communicated until the moment of opportunity, in order to prevent police intervention and retain the element of surprise. When the plan is shared with those assembled, it can be modified based on others’ input. For example, the route from Chicago Avenue to Lake Street has been traversed a number of times since the beginning of the uprising, but the participants could have chosen an alternate route if the police had decided to respond. The Hong Kong-inspired slogan “be water”—which was spray-painted on the walls of Minneapolis during the uprising and again on Saturday—emphasizes the value of being mobile and flexible in order to be able to change routes and destinations as needed.

On Saturday, the police never showed up, likely due to the opaque organizing and shifting department priorities following the rebellion—not to mention it being a busy holiday weekend.

Standing together in front of the empty shell of the Third Precinct with fireworks booming overhead as people spray-painted every available surface, we felt just the smallest reverberation of the uprising we experienced just weeks before. Unlike protests, which employ a means (e.g., a march or a blockade) to reach an end (e.g., sending a message or making demands), the events of the uprising and this past Saturday night blur this distinction. They create a kind of means-as-end, or means-without-end, in which the purpose is inextricable from the lived experience of the event itself. To fuse means and ends in this way, we have to move beyond the predetermined choreography of protest to a more transformative paradigm of action. “I’ll never forget that night” reads the latest graffiti written on the barricades surrounding the precinct, referring to the night of May 28 on which unrelenting crowds forced police to retreat from their station and established a brief yet real police-free zone—abolition in real time.

If the crowd intended to send a distinct message on July 4, it is that those who are currently facing the harshest repression from the uprising will not have to endure it alone. Hundreds are facing charges, including several people who are charged with arson by federal authorities. They will need our utmost support as they begin what will be a long and grueling process through the legal system.

While the revolt has subsided and momentum shifts gears, that does not mean that peace has returned to Minneapolis. In the words of Minneapolis-born rapper Reeves Junya, which are now inscribed on the walls of Lake Street,

“We don’t know peace, only gun smoke.”

Postscript on George Floyd Square

Meeting up at George Floyd Square seemed like fairly common sense, but it caused a mild local controversy. Some critics suggested that the square is a memorial, a somber place of Black mourning, and therefore the crowd’s celebratory vibe would be unwelcome and disruptive.

While the space is anchored by the large memorial to George Floyd, it is also large and heterogenous. There are barricades on each street for at least one block extending in every direction from 38th and Chicago. The square has also expanded to include an adjacent park. Within this area, in addition to the memorial, DJs play music, people cook and share food, preachers lead prayers, merchants sell T-shirts, supplies are distributed freely, gardeners tend a garden erected in the street, and lots of people hang out. Multiple demonstrations gathered at this square and departed from it on July 4.

This projection of the site as a space for mourning is not incorrect, but it fails to capture the full breadth of what is going on in the square or the emotional complexity of the environment. The uprising itself was driven by a powerful surge of joy emerging from the collective expression of rage and grief. As the sun set this past Saturday night, several fireworks exploded directly above the memorial itself, showing that the atmosphere of the space cannot be neatly summarized. It is a mistake to impose a false dichotomy between supposed (white) agitators who want to celebrate and (Black) mourners who want peace and quiet. Meeting at George Floyd Square could have created opportunities for people to make more connections outside already-existing social circles by inviting people who had not heard about what was going on.

Instead, confusion about autonomous and leaderless organizing methods sparked warnings that circulated around the square to discourage people from joining. As a result, the only participants were the ones who traveled to George Floyd Square with the intention of joining; even some of those who had showed up intending to participate but lacked personal relationships with other participants apparently chose not to join the march in the end. Those who were concerned about representing and managing groups of people ensured that those who marched to the precinct were separated from everyone else at the square, illustrating how such forms of political analysis can give rise to self-fulfilling prophecies.

Appendix: Graffiti from July 4

Behind the Third Precinct: Chinga la migra; Fuck 12; From the bottom of my heart… RIP to George Floyd and all victims of slave catcher violence.

Fuck MPD-Mpls; Revolution forever; Quit your job; Say her name Sandra Bland; Fuck 12; Literally ACAB; 1312.

Next door to the Third Precinct: Free ‘em all; Kill cops; Let me breathe; BLM; Fuck MPD.

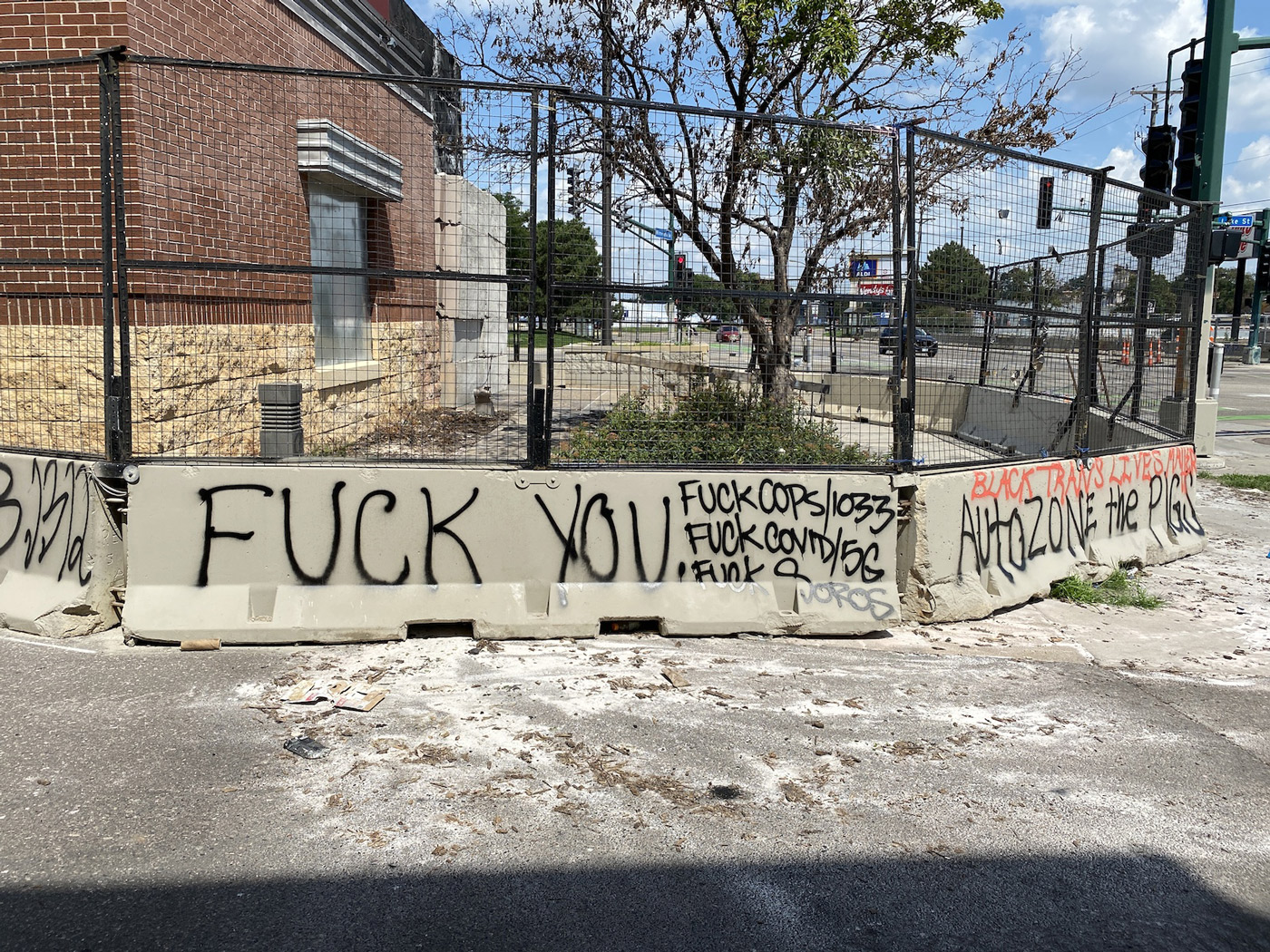

In front of the Third Precinct: Fuck you; Fuck cops/1033, Fuck COVID/5G, Fuck Soros; Black trans lives matter; Autozone the pigs.

Free them all; ACAB - every last one; Fuck 12; No retina scanners; Kill the pig in ur head; You lose pigs.

No peace; <3 HK [Hong Kong]; MPD [crossed out].

Burn em all; Smells like bacon; Free the prisoners.

Burn ‘em all; Torch em; Fuck 12; Kill killer cops.

Street barricades untouched from the night before: Burn more of these [arrow pointing to precinct].

I’ll never forget that night; Be H2O.

<3 HK; Fuck MPD; Burn 5 more.

Lets burn another; Lets kill cops.

We don’t know peace; 612 ain’t nothin to fuck with.

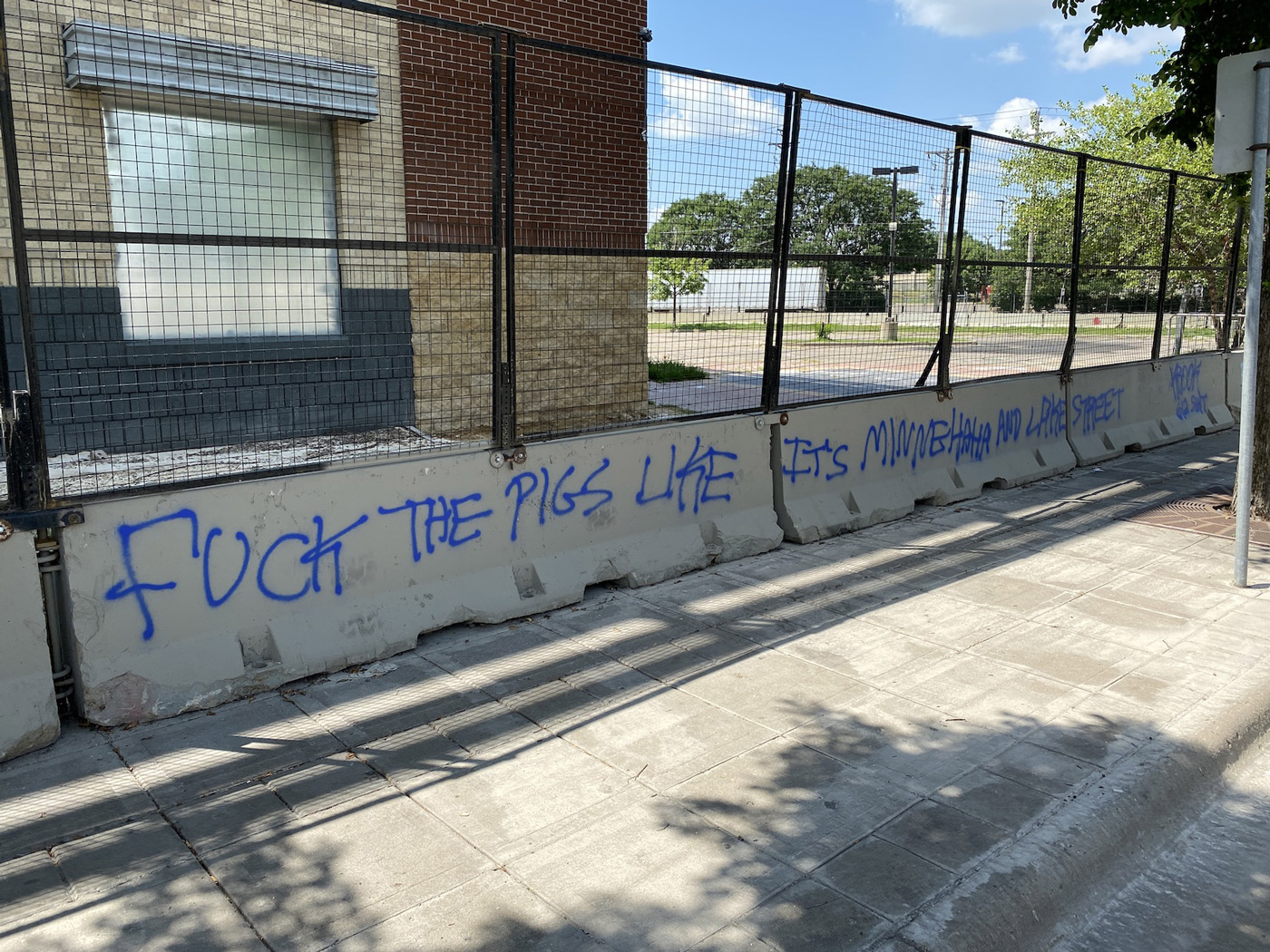

Fuck the pigs like its Minnehaha and Lake street [lyrics to Finna’s “Say”].

Burn the plantation; Kill pigs on sight.

Free all prisoners.

Free the prisoners; Kill cops; Remember May 28.

Burn them all; Layleen Polanco [transwoman of color killed in prison in New York]; George Floyd; Fuck 12.

Another can burn; Fuck 12.

Kill cops; Kill all cops.

Outside the former Autozone: I had a dream I got everything I wanted.

Outside the former Arby’s: No cops yes now [lyrics to Four Fists’s “Nobody’s Biz”].

On Lake Street: Abolir la policia.

ACAB; Free all arsonists; Kill all cops; George Floyd; Fuck USA; ACAB.

Free em all; Fuck 12; America is canceled.

Be water; Kill the cop in ur head; (And the other ones); BOES [moniker].

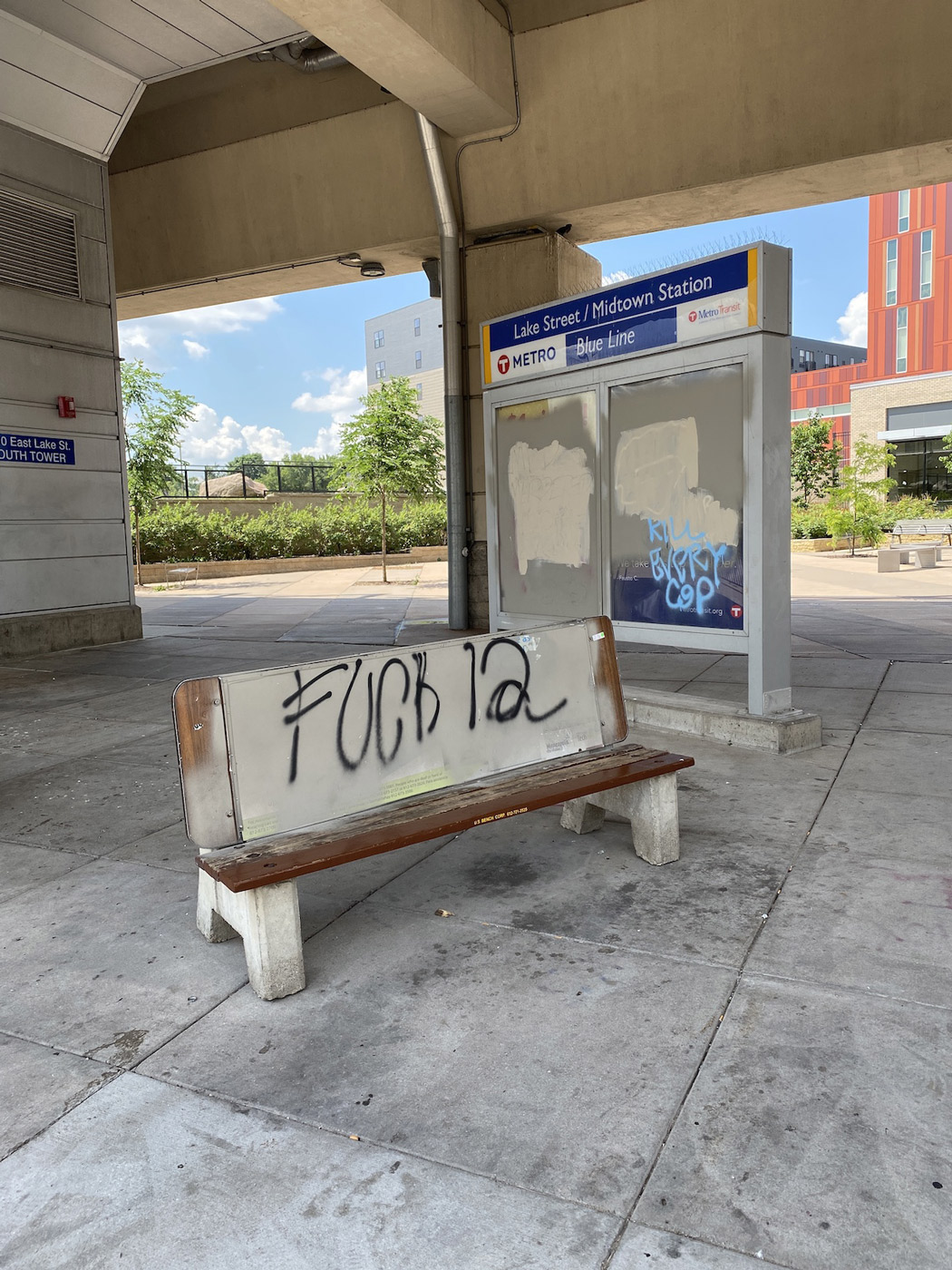

Fuck 12; Kill every cop.

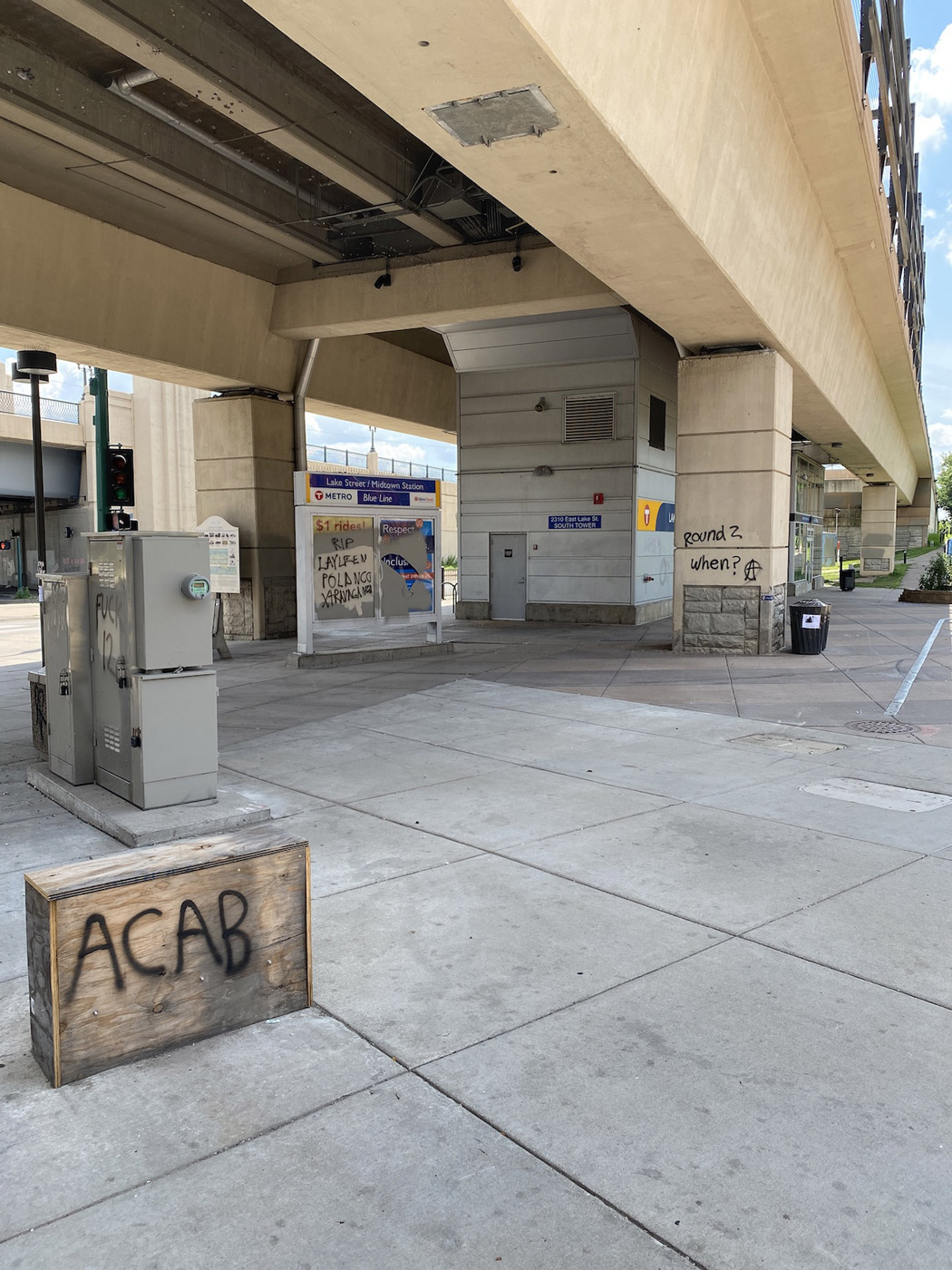

Fuck 12; ACAB; RIP Layleen Polanco Xtravaganza; Round 2 when?

ACAB; Defend looters; Fuck USA.

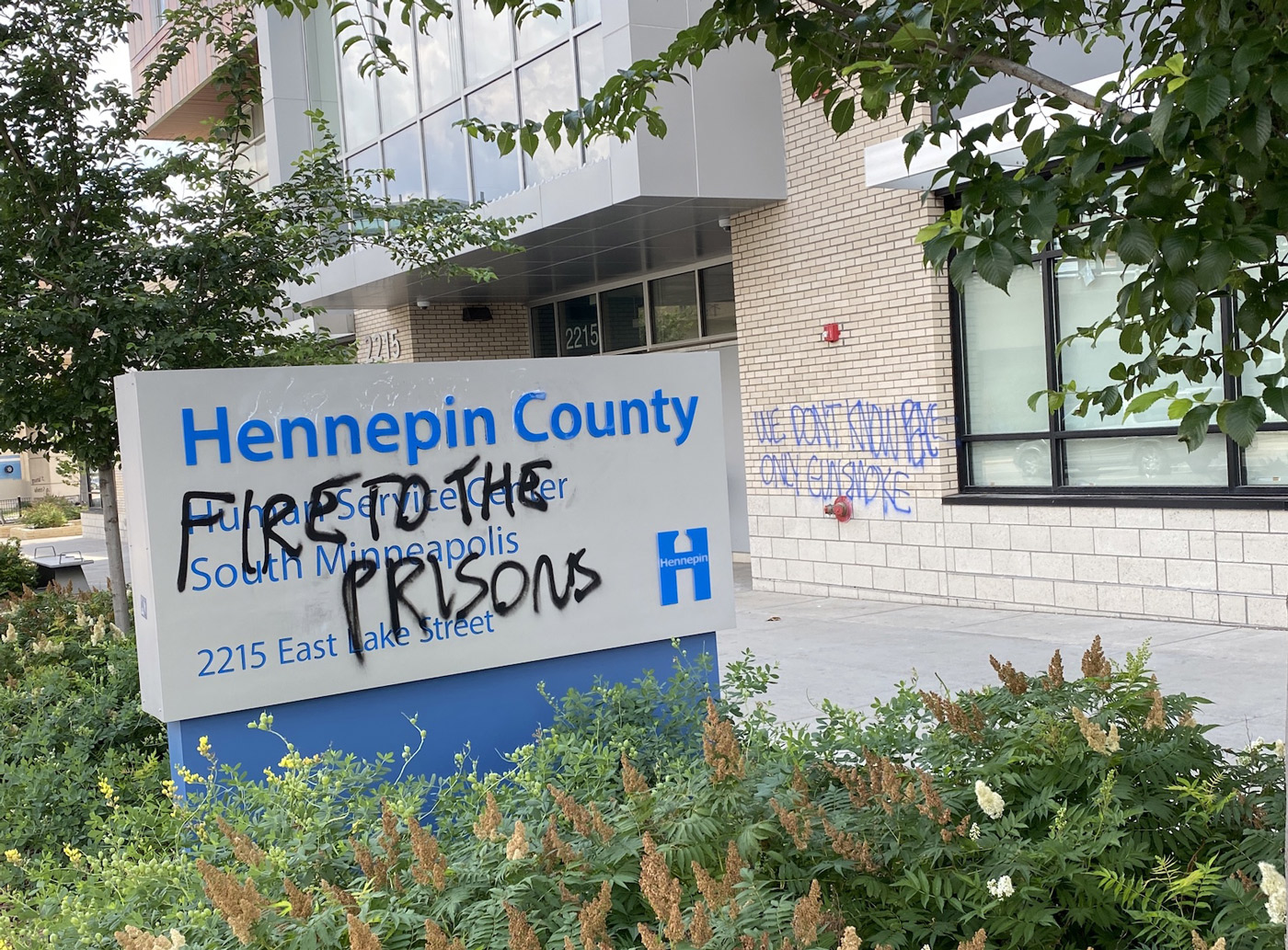

Fire to the prisons; We don’t know peace only gun smoke [lyrics to Reeves Junya’s “City on Fire”].

Free all rioters.

America is canceled.

Fuck 12; Autozone the MPD.

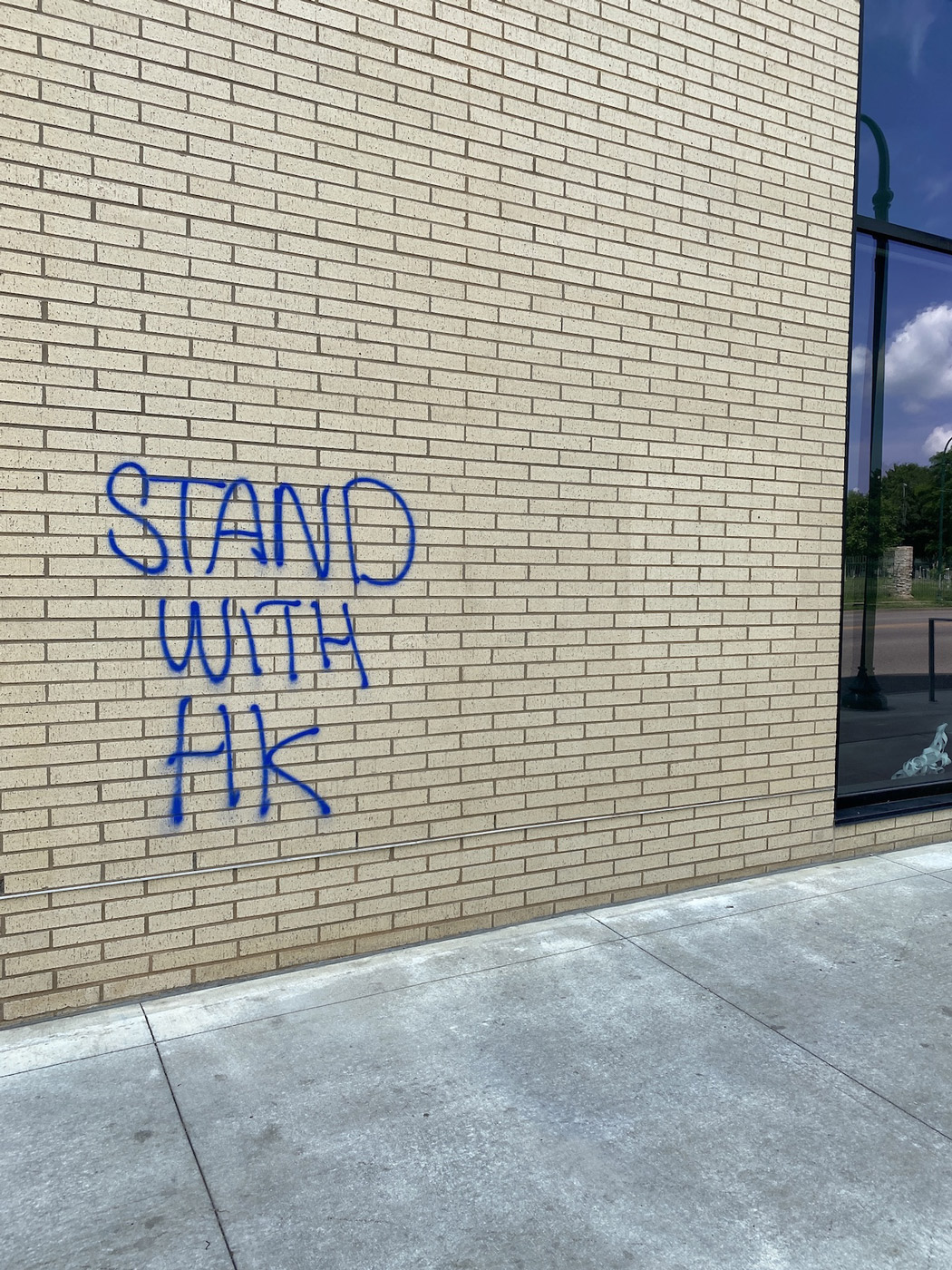

Stand with HK.

Burn another precinct; Layleen Polanco; Free ‘em all.

Two countries one virus, be water <3 HK; Layleen Polanco.

The owner of Cadillac Pawn shot and killed Calvin Horton, a Black man alleged to have been looting the store, during the uprising. The store’s facade is regularly defaced: Fuck you!!; Fuck this store; RIP Calvin; Fuck 12; Fuck this.

Amnesty for all rioters.

Free the rioters; and all prisoners.

We dream of a better world for everybody; Fuck 12; Everybody hates the pigs; No justice no peace; abolish the cops.

Free the rioters; Free all rioters.

Another untouched street barricade: ACAB.

Fuck cops; George Floyd; F12.

ACAB; Fuck 12; Fuck 12; ACAB; ACAB.