Today, rather than speaking of the working class, it might be more precise to speak of the endangered class. In this account, a delivery driver at the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic in Manhattan describes the conditions that workers are exposed to and the stark class relations between the vulnerable and the protected, concluding with a call for solidarity among all on the receiving end of capitalist violence and inequality.

For a Solidarity of Condition and Position

With all these calls coming out for solidarity among all humanity in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, I’d like to be specific about where my solidarity lies and to encourage others to do the same. While some of us are risking our lives, others are pulling the strings from above as they ride this pandemic out in comfort. While “we are all in this together,” we are not all enduring the same conditions or facing the same risks.

The reality that we have been numb to for so long is coming into focus. It has become impossible to conceal the inconsistencies in the ways that our labor is valued, to ignore all the ways that we are at the mercy of those above us in the hierarchy. They have done everything in their power to make us blame ourselves and each other for our situation, but it’s no longer possible.

I am writing from a mandatory quarantine outside of the United States. I spent March in Manhattan working as a so-called “essential worker” delivering food to the rich as the pandemic spread through the city. Like so many people in my situation, I suspect that by now, I must have already been exposed to the virus. If I contracted it, I was fortunate enough to have no symptoms. As a lower-class resident of the United States, of course, I never had access to a test, so this is just speculation.

I’m not happy to be able to say “I told you so” about the situation we find ourselves in today. At the beginning of March, many people were still dismissing me as paranoid. It wasn’t that I was afraid of getting sick. For weeks, I was trying to explain to friends that they have to understand how the food they eat reaches their plates, where their medications are made, and how the division of a globalized world into consumer nations and producer nations could cause serious issues when it comes to us getting access to basic sustenance. Now everyone is talking about these things.

The first few weeks of March in New York City were like a roller coaster climbing to the top before a steep plunge. The tension just built and built. Every day, I agonized about whether I should flee to the countryside or try to return early to my home abroad. I had to weigh both of those options against the money I was making and the prospect of a future in which it might be much more difficult to obtain employment.

Biking across the boroughs, I could feel something strange building up. Most people who took the situation seriously expressed it by shopping or leaving the city. There was rampant panic buying and an exodus of those with second homes or families to stay with outside the city. Near the projects and poorer neighborhoods, I could still find toilet paper and disinfectant, since fewer people there could afford to hoard. Many distrusted the government; many didn’t care; many had witnessed things even worse than a pandemic; and many felt helpless in the face of the confusion and fear that arrives with the unprecedented.

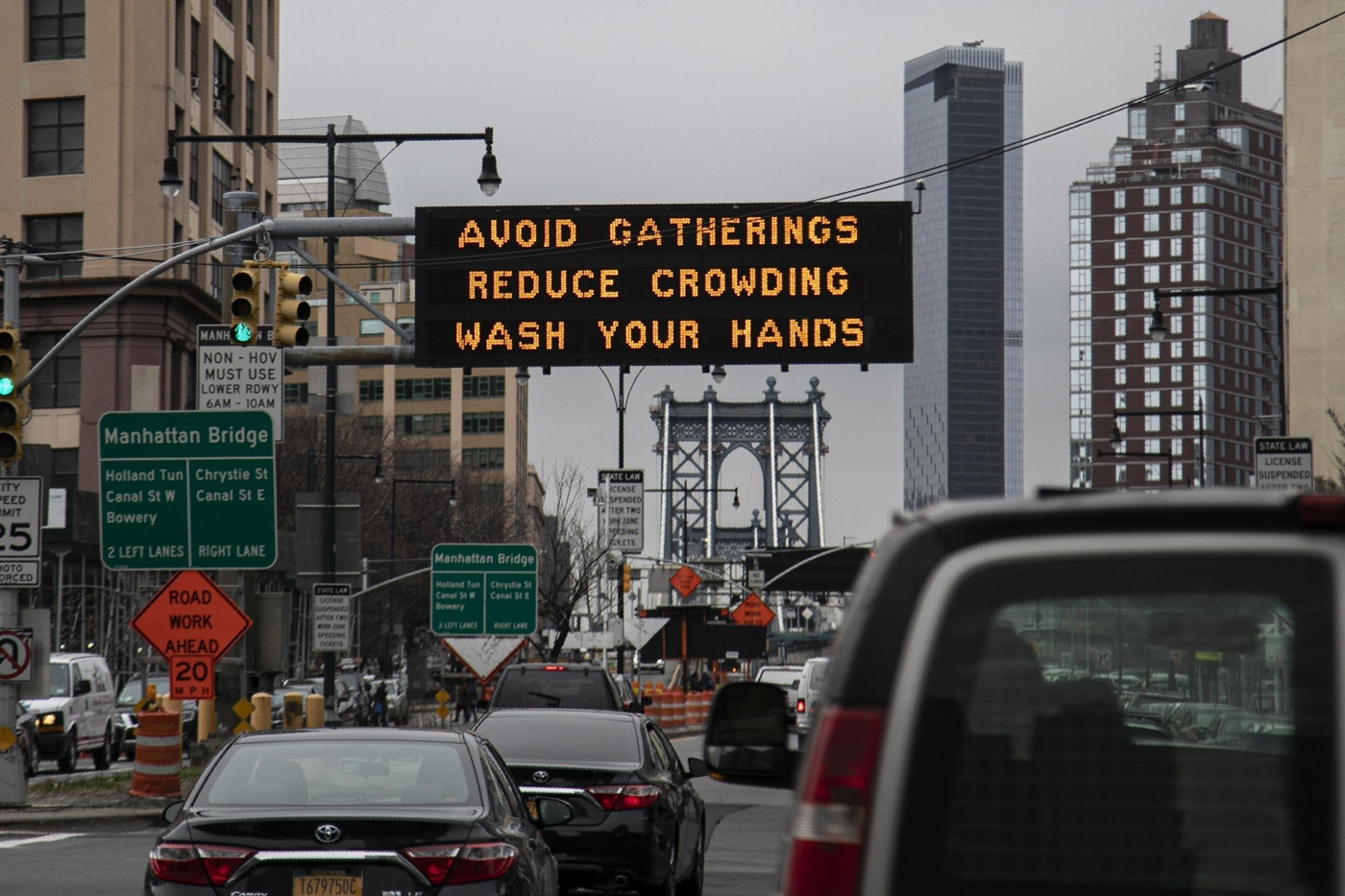

Those who wore masks and gloves were considered eccentric up until the third week of March. People were still promoting parties up to the very last day they could. Those who were able to work remotely were sent home first, while everyone else remained at work. Some of the more affluent private schools were cancelled shortly after that. Then the suburb of New Rochelle was put into lockdown, but everyone else went about their business as if nothing was happening. When Mayor de Blasio finally closed the schools and forced the restaurants and bars to shutter, the reality of the situation finally began to settle in. All the reasons for high rent, all the distractions from the stress, all the rationalizations were suddenly gone. Ignorance was no longer an option.

The weather fluctuated the way it has over the last few years, prompting cynical comments about climate change, but everything just seemed dreary to me. Hugs became more and more awkward. Soon, I reserved them only for people I wasn’t sure that I’d see again. I was staying with a friend who tested positive for COVID-19 and has since recovered. I house-sat for another friend whose partner has died of the virus.

Manhattan became emptier and more and more frightening as the tension increased. In contrast to the September 11 attacks, or to Hurricane Sandy, when we saw a blackout of Manhattan on Halloween that I will never forget, the pandemic didn’t hit all at once in an obvious way. It was an invisible impact in slow motion—it was hard to grasp what was coming or to what extent it was already underway. It was chilling to see friends who had recently dismissed my concerns as paranoia coming to me for advice. It made my blood run cold to watch people who had always tried to calm me down slowly growing more fearful as their livelihoods were cut off. The biggest, busiest city in the United States was shut down by an unseen force. In the end, I escaped, leaving many of the people I love to wait for the unknown.

During my final weeks in New York City, I was deemed an “essential worker” because I brought food directly to rich people’s doors in order to ease their risk of exposure. I see people posting “stay at home” memes on Instagram, never pausing to acknowledge how the fusion meals they post photos of alongside them are still possible during this time.

It’s hard not to scoff at the cheers of the rich I see in recent videos taken from Manhattan. Apparently, the ones who didn’t escape to their summer homes take a moment each day to appreciate delivery people and other workers who have been taking the risks for them through this pandemic. I watch these clips and their petty gratitude leaves me unmoved. My memories of being disrespected, degraded, and underpaid are not dispelled by a moment of flattery from the comfort of Manhattan’s luxury buildings. We deserve more than a little applause.

I worked delivery jobs up until the day I took what I feared was my last opportunity to return to my partner and a more affordable life abroad. I knew the risks of travel, but I was more concerned about what the future would bring and what my economic position would be in it. Most of my friends in New York work service and hospitality jobs—or used to. After every job I had intended to work was cancelled, the app-based delivery jobs I turned to as my last resort were pretty much all that remained for those of us who lacked the privilege to work remotely. I still get notifications informing me of one-off work opportunities. I wonder if each one I pass up is a meal I won’t be able to eat in the future.

So I resent the applause of the wealthy. I wish I could publish the names and addresses of everyone I had to deliver to, along with the exact amounts of the tips they gave me. I wish I knew the net worth of each person I delivered to so I could calculate my anger precisely.

I delivered to skyscraper condominiums across Manhattan. At first, when I showed up, the doormen would greet me with a smile, assuming I was a visitor or resident because of my light skin. As soon as it came out that I was a delivery person, they would suddenly change tone. The transition was intense. You wonder how they choose these guys.

Other times, I was forced to enter through disgusting piss-covered “poor doors”—secondary entrances for service workers and low-income tenants. This doubled the time it took me to enter and leave buildings. It also forced me to come into contact with more building staff, increasing my risk of exposure.

Still other buildings wouldn’t allow delivery people up at the request of tenants. I assume they considered us dirtier then the bags we delivered. While this was degrading, it was also a relief.

I delivered to penthouses as high as the 73rd floor only to receive no tip at all. Generally, the tips were shit. Maybe this was because the rich are nervous about what the future will bring for them. (The New York Post has since reported on customers pretending to offer big tips and then cancelling them afterwards.) The tips were so bad that I was afraid to ask for no-contact deliveries, as some customers scoffed at my requests. As a service worker, how dare I protect myself?

I won’t forget one of my last nights delivering. I did my best to reject delivery requests to Walgreens and Duane Reade pharmacies, partly because it was just too degrading to take jobs in which my sole function was to reduce the risk that people wealthier than me had to face, but also because I knew that the products people were trying to order were already sold out.

These apps force you to be the one to bear the consequences when someone requests a product and it is sold out. They don’t give you the option to cancel the job when the product is unavailable—you have to say you are unable to complete the order. Consequently, you not only forfeit travel compensation for biking to the location, you also can forfeit delivery consistency for the remainder of your shift.

That night, instead of thermometers and toilet paper, someone ordered 50 boxes of laxatives, a purchase of $250. I bit the bullet and took the order.

I biked through the silent streets of Manhattan’s upper West Side. Even in the eerie absence of traffic, I still had to obey the traffic lights, lest the police ticket me for delivering “essential” services. I miss the old school days of NYC before “quality of life” policing. In those days, riding a bicycle, you felt unstoppable.

I got to the pharmacy and went in. It felt like I was stepping into a giant petri dish teeming with COVID-19. Of course, as at all the pharmacies in Manhattan, everything was sold out, including this person’s 50 boxes of laxatives. I called the customer to beg her to cancel the order—my only chance to keep the pathetic $2.36 that I get for the “pick up” part of the delivery process. More importantly, it was also the only way to avoid having to cancel the order myself and risk losing my spot in the app’s almighty algorithm.

“Of course they are out, ugh!” she answered when I informed her. She demanded that I be the one to cancel, because she knew she’d lose her $2.36, reciting the standard “It’s your job, it’s not my fault.” She had used me to confirm what she already knew so she wouldn’t have to enter a pharmacy in the epicenter of the epidemic, but she had the audacity to demand I cancel so she wouldn’t have to give me any money. I ended up begging her, trying to explain that I had biked through a pandemic to check on the product for her. I offered to send her a photograph confirming that I went into the store and saw that the product was out. She replied that it wasn’t her problem. I moved on to the next job, obsessing about her selfishness and entitlement. After 30 minutes, she canceled.

She was placing a $250 order and she demanded that I forfeit all dignity so she didn’t have to “waste” $2.36. I am certain that if I had not spoken good English, I would have received nothing at all for my pains. Of countless stories like this, this one remains fresh in my memory, as it took place the last night I was working in New York.

This is why, when the wealthy and powerful speak about solidarity, it leaves me cold. I reserve my love and appreciation for those who are not only afraid of getting sick at this time, but who are forced to risk being infected in order to survive—those who are struggling to figure out how to eat, how to keep a roof over their heads, how to prepare for an even more precarious life in the economic recession ahead. I reserve my love and appreciation for those who have always been underpaid and replaceable, who are on the front lines of the pandemic. Now we are essential? Now we are heroes? What were we before? What will we be when this ends?

It’s shocking how people continue to rationalize the value of leaders and institutions that have utterly failed to do anything to help us survive this catastrophe.

How is it possible that police officers are still getting respect as “emergency workers” when they are running around without masks on, infecting people throughout the city, attacking children on the subway? How can anyone set them alongside nurses and grocery store workers, who are dying dozens at a time so we can eat? Hasn’t the role of police in the spectacle of the end of the world shown their true purpose clearly enough, if it wasn’t already obvious?

ICE agents have been hogging N-95 masks so they can protect themselves while they continue disappearing undocumented people, spreading the infection as they terrorize communities and separate children from their parents. Prison guards are spreading the virus to prisoners whose only means of protest is to stage revolts at great risk to themselves.

I saw police pulling over delivery workers for bicycle traffic violations in Manhattan when deliveries surged in response to the virus. This is a typical tactic via which the New York Police Department fulfills their monthly ticket quotas. Grocery workers, agricultural workers, those working in transportation, delivery people, EMTs, hospital staff helping to keep us alive under what amounts to martial law—all these people are all truly deserving of my gratitude. How can anyone place the police alongside these courageous individuals? What do they do to sustain and care for us?

The United States has passed a two trillion dollar stimulus plan. I don’t even know if I am eligible for the check or for unemployment, thanks to my being poor and working gig to gig all these years. The website says those low-income taxpayers should wait—until the others have been paid first, I’m guessing. I read that only 30% of the stimulus goes to individuals ($602.7 billion). The other 70% is split between large corporations ($500 billion), small businesses ($377 billion), state and local governments ($339.8 billion), and public services ($179.5 billion). As far as I see, considering that the airlines alone are getting over 10% of the corporate bailouts while I am still fighting them for a refund on the flights they cancelled on me, I see this as a big fuck you to me and everyone like me. Just one more reminder that in this society, my value is conditional at best, determined by the logic of the market and the priorities of the ruling class.

If the way that the stimulus package is distributed doesn’t make their priorities clear enough, governments are simultaneously rushing to maintain, reconstruct, and usurp power.

In places like Russia and Israel, the authorities are exploring new opportunities in cyber-policing. In places like Hungary, the rulers have already used this opportunity to transition to outright dictatorship. In places like Kenya, India, and the USA, we see them containing slums, prisons, and refugee camps as acceptable death zones. In Greece, on International World Health Day, police attacked a gathering of doctors and nurses at Evaggelismos hospital in Athens who were calling for more safety resources. Experiments in martial law are taking place everywhere under the guise of lockdown, supposedly for our protection—but those in power seek to protect their position, not to protect us. Nationalists and fascists are using this as an opportunity to advocate for bigger border walls and prisons. We’ve even seen some scientists calling on world governments to go to Africa or other populations that are less valuable to the global economy to carry out the experiments through which they hope to generate vaccines.

A sign of life: a neighborhood in Brooklyn singing “Juicy” by Biggie Smalls while on Coronavirus lockdown.

So I want to call for another solidarity. A solidarity between those who have a lot more to worry about than the virus alone. A solidarity among all who have to fear what governments and their police will do to us. A solidarity between everyone who is waiting in terror for even more precarious conditions to arrive as the rich scramble to enter the post-pandemic world still standing on the shoulders of us expendables. A solidarity that includes refugees and others who have lost their homes. I want to share my gratitude with those who deserve it—those with whom I share condition and position.

When in our lifetimes has the mathematics of our value been more flagrantly displayed? Politicians, police, and billionaires are struggling to rationalize their comfort and privilege; in the United States, they are being more honest than ever before about what really matters to them.

We need a solidarity that has nothing to do with politicians and plutocrats, nor with the police who protect them. Let us look on those beside us with love and a mutual commitment to protect our humanity, just as we regard those above us as our enemies. Those who are looting in southern Italy are expressing the same passion for life as those who looted New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina in order to feed their neighbors. These are the people who are setting a good example, not the police, not Governor Cuomo.

Today, my own quarantine period is about to end. But my mother is working in a grocery store at nearly 70 years of age, while my father, who is in a hospital with a compromised immune system, has tested positive for coronavirus. If concerns about the market had not been prioritized over concerns about life, I am certain my father would have been spared this virus, as he was isolated since the beginning of March in a nursing facility. My mother cannot distance. My father couldn’t distance. But many can afford to sidestep these risks. They are not facing the same pandemic. They don’t deserve my solidarity.

We are not all in this together—but most of us are.

Return to normalcy? Never again.

A food delivery worker in China.