This year in France, the traditional day for celebrating the struggles of the late 19th century and the introduction of the eight-hour day was part of a much larger sequence of struggle. As May Day approached, the French government remained caught in a political crisis created by the still untamed yellow vests movement. Because we have documented May Day 2017 and 2018 in Paris and the entire trajectory of the yellow vest movement, we can identify the new strategy of repression that the state is employing and evaluate its strengths and weaknesses. Globally, it appears that governments from France and the United States to China and Nicaragua have no real plan for dealing with the unrest generated by spiraling social inequality except by ceaselessly escalating the violence they perpetrate against human beings. The past year’s clashes in France place it near the front of this process of escalation; the following analysis will be informative to anyone interested in continuing to organize protests and bringing pressure to bear on the authorities despite their efforts to impose “order” by brute force.

For more background on the yellow vest movement, you can read our previous articles here. You can watch video footage of May Day 2019 here and here.

“We are not giving up.”

For the past several years, France has experienced numerous waves of resistance to capitalist projects and political reforms. This succession of conflicts has underscored the increasing difficulty governments face imposing their neoliberal agendas on the population, while enabling anarchists and other autonomous rebels to connect with new sectors of the population. Some ideas and practices that originated in anarchist and anti-authoritarian circles have spread to other demonstrators, too.

This evolution started during the movement against the Loi Travail when students and other demonstrators who refused to march alongside trade unions decided to take the head of the procession, creating the cortège de tête. As intense clashes with police forces became the norm, demonstrators who had not previously engaged in street confrontations learned defense tactics such as wearing goggles and covering their faces for protection against tear gas and police surveillance.

Over the following years, the cortège de tête continued to attract more and more demonstrators, most of them disillusioned by the lack of political conviction of the traditional trade unions’ march. During May Day 2018, the leading part of the demonstration drew almost as many participants as all the trade unions together. To some extent, the cortège de tête has weakened and hastened the decline of trade unions in the French political scene. The latter have more and more difficulties portraying themselves as defending workers’ rights and fighting against the government’s neoliberal decisions.

A magnificent parade float designed to carry projectiles and protect demonstrators from police violence.

More recently, the yellow vest movement took everyone by surprise as some of its participants—many of them unfamiliar with demonstrations and social struggles—engaged in intense street confrontations and property destruction without waiting for anarchists to show up. They repeatedly succeeded in creating chaotic situations outside the zones controlled by police. This reshuffled the cards of social protest in France and allowed anarchists and anti-authoritarians to revise some of their tactics. Ultimately, yellow vesters and radicals began fighting side by side during the weekly days of action to such an extent that, for May Day 2019, autonomous rebels invited yellow vesters to join them in the cortège de tête.

The authorities fear these informal alliances and the increasing phenomenon of rioting as a form of political action. If more and more demonstrators continue embracing our tactics, refusing to dissociate themselves from the most “radical elements,” and engaging in property destruction and street confrontations against police forces, the government won’t be able to continue to fool people with the classic argument that “dangerous rioters wearing all black are threatening the safety of normal demonstrators and the lives of good citizens” to justify its brutal repression.

This is why, from members of the current government to yellow vesters and anarchists, everyone knew that during this May Day, the situation would be explosive in the streets of Paris. This article picks up where our previous analysis left off, in the aftermath of French President Macron’s press conference a few days before May Day.

A street confrontation in Paris during May Day 2019.

Building makeshift barricades.

Setting the Trap

For years now, it has been a ritual that every time an important day of action approaches, the authorities increase the pressure beforehand via official communiqués and shocking statements in the corporate media in order to spread fear among potential demonstrators and discourage them from joining the festivities.

With Didier Lallement as the new Prefect of Police in Paris, this psychological warfare is in full use. After the riots of March 16, Minister of the Interior Christophe Castaner said to the newly named Prefect that “to protect demonstrations is to crush the riots […] I ask you for zero impunity.”

From left to right: Didier Lallement (Police Prefect of Paris), Laurent Nuñez (Secretary of State to the Minister of the Interior), Christophe Castaner (Minister of the Interior).

Since Lallement took this position, we have seen a clear shift in law enforcement strategies in the Parisian streets: numerous preventive searches and controls on the outskirts of demonstrations; more mobile police units on the ground; immediate use of tear gas and rubber bullets as soon as the first clashes erupt; police breaking marches up into several parts and kettling them; and a free pass from the executive power for police to engage in hand-to-hand confrontations. All of these have increased the level of repression and violence during demonstrations.

Some radicals and yellow vesters were determined to make Paris the new capital city of rioting for the 2019 May Day celebration. The government took all possible precautions to keep the situation under its control. May Day was a test to see if the new law enforcement approach would work.

The new normal: the last vestiges of social peace in France are evaporating.

Paris on May Day 2019.

To this end, the government decided to think big. About 7400 police units would be deployed in the streets of Paris. “Mobility, responsiveness, prevention of violence, and the systematic arrest of troublemakers” were the main guidelines given by the Minister of the Interior, who said that the authorities were expecting between “1000 and 2000 radical activists” and that the latter could “possibly be reinforced by individuals from abroad who might try to sow disorder and violence. They could be joined by thousands of what are now called ultra-yellow, yellow vesters who have gradually become radicalized.” Official statements like this highlight the typical strategy via which governments seek to construct both domestic and foreign enemies during political crises in order to legitimize their reactionary and authoritarian measures.

In order to maximize their control over the situation, the authorities also designated several restricted areas, as they have during yellow vests demonstrations, and canceled or relocated several events scheduled for May Day. A march against climate change that was supposed to join up with the traditional afternoon demonstration was simply canceled by authorities. This cancelation could be related to the fact that a call was made to create an offensive bloc during this morning march. A yellow vest demonstration scheduled for the morning was also canceled, then eventually assigned a new route. Finally, the traditional anarchist procession that takes place every May Day was also rerouted.

The yellow and black wave. For May Day 2019, yellow vesters answered the invitation from autonomous rebels to join them inside the leading procession.

Officially, the government justified these prohibitions by saying that they were too close to restricted areas. We believe that by containing morning demonstrations to several distinct districts of Paris and preventing any connections between these actions and the traditional May Day march, the authorities aimed to control the waves of demonstrators so they could implement their new law enforcement strategies and carry out preventive searches, controls, and arrests upstream of the afternoon gathering.

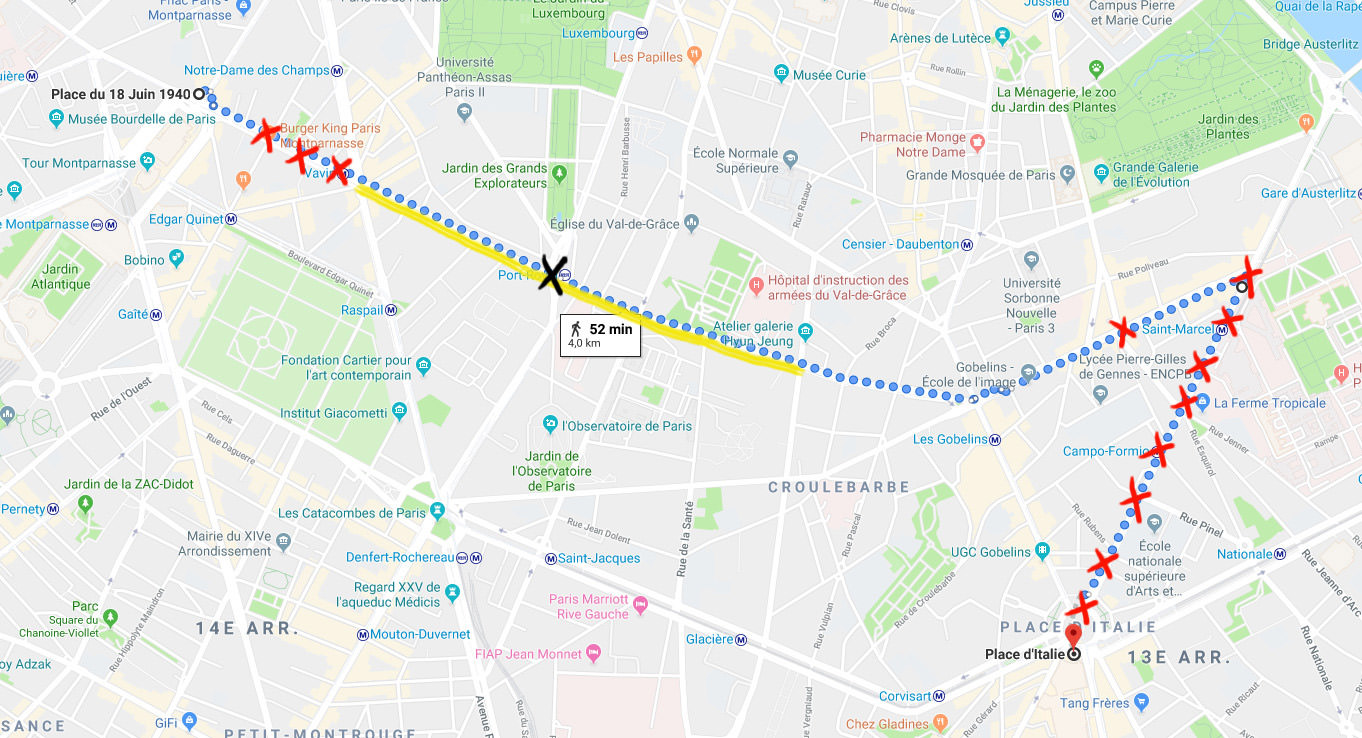

Another strategic advantage the authorities had for May Day was the fact that they were the ones to set the route of the afternoon May Day march. This year, the procession was supposed to leave Montparnasse in order to reach Place d’Italie, following an approximately 4 km long route—relatively short for a Parisian demonstration—through major empty boulevards. For the occasion, authorities asked the 584 shops located along the route to remain closed for the day and to barricade their front windows. The afternoon demonstration was obviously a trap set by authorities: large boulevards where the crowd of protesters could easily be surrounded and attacked by police forces; few targets for rioters, except at the beginning of the demonstration near Montparnasse and in the Boulevard de l’Hôpital; and the now-traditional conclusion at a major square where police could trap every demonstrator in a large kettle.

40,000 people joined the festivities on May Day 2019.

In addition, as usual before May Day, Christophe Castaner and Laurent Nuñez—Secretary of State to the Minister of the Interior—met with trade union leaders. The latter shared their concerns about possible acts of violence during the demonstration and discussed law enforcement strategies and possible alternatives with the authorities. To reassure trade unionists, Castaner held a press conference to announce that: “our first responsibility is to guarantee the right to demonstrate freely, and to demonstrate while being protected.”

One article explains that, at this same meeting, the authorities told the trade unions of their intention to attack the head of the procession at some point during the march—somewhere between the intersection with Boulevard Raspail and Rue de la Glacière. To make this easy, they asked trade unions to disassociate themselves from the cortège de tête and to continue to demonstrate via an alternative route. According to the article, the trade unions seem to have rejected the offer, since some of their sympathizers are usually present at the head of the demonstration.

However, we personally remained unconvinced by the trade unions’ response, as at numerous occasions in the past, they have showed their true faces by voluntarily disassociating themselves from the rest of the demonstration, confronting demonstrators who are less obedient and passive than themselves, or using the very same discourse as the authorities to denigrate rebellious actions and individuals. Let’s make this clear: in France, there is absolutely no doubt that there is complicity between trade union leaders and the defenders of the existing order. Yet again, the events of May Day 2019 confirmed this.

On the eve of May Day, tensions ran high. No one knew how the situation in the streets would turn out. Several comrades discussed strategies, concerns, and determination with lundimatin in an article entitled “May Day Demonstration: What to Expect from the ‘Black Bloc’?” Others, in an optimistic and passionate text, suggested that May Day 2019 would be the day when “everything would be possible!” Everyone agreed on one thing: the following day would be decisive, despite the suffocating law enforcement strategy that was waiting for us. The main question was whether we could succeed in thwarting the trap set by the government.

In blue, the official route of the May Day procession; in yellow, the zone where police told the unions that they would attack us. The black cross shows where the CGT stopped and dissociated itself from the rest of the demonstrators; the red crosses show where major confrontations took place.

Q: Even inside the kettle? A: Even inside the kettle.

Escaping the Trap

Due to the large number of actions that took place on May Day 2019, we won’t provide an exhaustive report of everything that happened the streets. We’ll focus on the major events that structured the day and some interesting initiatives and situations that we witnessed.

Anarcho-syndicalist unions gathered at Place des Fêtes the way they do every year to pay tribute to the anarchist origins of May Day. However, due to the context, the anarchist demonstration was not permitted to march towards République. Instead, it was supposed to end at Stalingrad—another location where it would be easy for police to kettle everyone if they wanted to. Around 11 am, as more and more people arrived at Place des Fêtes, police forces, including riot police units and officers in plain clothes, began patrolling the square and searching individuals carrying backpacks. The anarchist procession finally started around 11:30 am. It was hundreds strong.

The crowd marched rapidly through the streets of the Parisian popular district, followed closely by police trucks and riot police units on foot. At almost every intersection, firemen with extinguishers were waiting, as if our objective for the morning was to set everything on fire—which was especially unlikely in this working-class district. The general atmosphere of the march was strange; very few targets were attacked. No doubt part of the crowd was already focusing on what would be waiting ahead of us and how to outmaneuver it. Little by little, as the procession approached its final destination, groups of demonstrators left in order to join the starting point of the afternoon march on time.

The first confrontations of the day started at Montparnasse, the departure point of the May Day procession.

In the end, what remained of the anarchist procession decided to continue its course through the streets of Paris in a spontaneous wildcat demonstration, before disbanding when police forces and members of the BAC (Brigade anti-criminalité, “Anti-criminality brigage”) showed up. During the morning, other wildcat initiatives took place outside the official demonstrations. Unfortunately, they didn’t last long, as police brutally dispersed them.

In the meantime, at Montparnasse, the situation was already charged. Since the morning, thousands of people—from trade union sympathizers and passersby to yellow vesters and radicals—had been gathering in the main boulevard. The government’s decision to cancel or change the course of some morning demonstrations had not pacified the situation—on the contrary. Around 1 pm, tired of remaining static while waiting for the official hour to arrive to start the demonstration—and despite a massive police presence in the area—some anarchists and other rebellious demonstrators took action.

Tired of waiting for nothing, an offensive bloc tried to attack its first target.

Clashes on the Boulevard du Montparnasse.

Moving swiftly, some people attempted to constitute a bloc at the front of the procession to attack La Rotonde—the restaurant where Emmanuel Macron celebrated his presidential victory in 2017. For a full hour, intense street confrontations took place between demonstrators and police near the intersection of Boulevard du Montparnasse and Boulevard Raspail. Interesting to report, it was during this major phase of confrontations that Philippe Martinez, the leader of the CGT trade union, had to be exfiltrated momentarily from the demonstration—drawing boos and insults from several demonstrators—due to the explosion of a tear gas canister near his position. As if more proof were needed that making backroom deals with authorities doesn’t protect you from their weapons in the streets!

But what is more interesting here is how he reacted to this commonplace event. (We say commonplace because nowadays, what is more ordinary than breathing tear gas during a demonstration?) Yet once the situation calmed down a bit, Martinez took the occasion to denounce “an unprecedented and indiscriminate repression following the acts of violence of some,” before adding “the police has charged the CGT, a well-identified CGT, this is a serious matter.” Besides the voluntarily dramatic tone of his statement—remember that trade union leaders are here to play a specific role on the political stage—the CGT leader didn’t condemn police brutality per se, but only the fact that during confrontations, police forces attacked some CGT members. In other words, police violence is acceptable as long as it doesn’t target trade union sympathizers.

Police forces protecting La Rotonde, the restaurant where Emmanuel Macron celebrated his presidential victory.

Typical weather in Paris: a rain of tear gas canisters.

The situation created difficulties for demonstrators who wanted to join the main procession. Approaching the Boulevard du Montparnasse, all access was blocked by police lines. If you wanted to enter the perimeter, you had to submit to a complete search. Consequently, hundreds of people were wandering around the police checkpoints, going from one street to the next to see if there was a way to enter without being controlled. This confusing situation was the occasion to engage discussions with other demonstrators and to exchange important information. Some people, who succeeded in leaving the zone of confrontations, were already shocked by the level of police brutality, while a group of yellow vesters mentioned the fact that they saw with their own eyes part of the CGT procession retreating during the confrontations, leaving rioters and other demonstrators alone in front of police forces.

As planned, around 2:30 pm, the afternoon march finally started. As the impressive crowd was slowly walking towards its destination, some police checkpoints decided to release the pressure and let people enter the “secured perimeter” without submitting to a search. Police were still sporadically stopping and checking anyone they considered “suspicious,” as well. Once on the main boulevard, the compact crowd of protesters struggled to move forward, due to the numerous police cordons present on each side of the street in order to protect potential targets. However, waves of individuals were determined to get past the trade union procession in order to reach the cortège de tête.

Once we reached Port-Royal, the CGT—located at the front of the trade union procession—suddenly stopped. People continued to get around its security service in order to reach the tail of the cortège de tête. This situation was clearly no coincidence. We were right in the middle of the zone where the authorities had asked trade union leaders to disassociate themselves from the leading procession in order to facilitate their trap. We took this opportunity to ask one of the members of the CGT security team why they were suddenly stopping to create a gap between themselves and the cortège de tête. The answer was an embarrassed “I don’t know what you’re talking about.” Once again, the CGT was blatantly assisting the authorities in closing their trap around the “dangerous individuals of the leading procession.”

Nevertheless, the cortège de tête continued its route towards Place d’Italie. Almost no signs of confrontation were visible on the Boulevard de Port-Royal. The presence of riot police units in the boulevard and at almost every single intersection was clearly dissuasive. However, the diverse crowd of thousands remained determined, chanting anti-police and anti-capitalist slogans as well as the now classic “Révolution!”

Once people turned and entered the Boulevard Saint-Marcel, the tension suddenly increased. Some of us knew exactly what was awaiting us. We were approaching the final destination of the demonstration, which meant that if authorities wanted to strike hard at the cortège de tête, they would do it very soon. Police forces were present in every single neighboring street. As the procession entered the Boulevard de l’Hôpital, the crowd began to tighten up. Police trucks and riot units were blocking the main boulevard towards the Austerlitz train station. Our only options were to retreat or to continue towards Place d’Italie. As the crowd slowly marched toward the square, we realized that the cortège de tête had been cut in two by police forces. Ahead of us, water cannon trucks and police lines blocked the boulevard.

Beyond them, near Place d’Italie, several hundred people who constituted the very head of the cortège de tête engaged in impressive street confrontations with police forces. They created numerous barricades, set things on fire, and attacked police with projectiles. The crowd even attacked the police station of the 13th district of Paris, which was heavily protected by anti-riot fences for the occasion. Extremely intense fights continued at the main square, where police beat, dispersed, and arrested protesters.

The police station of the 13th district of Paris, behind clouds of tear gas.

Courageous comrades resisting a water canon.

Down the Boulevard de l’Hôpital, a newly constituted bloc was trying to reach the front of the remaining procession in order to face the police lines. Without further delay, a heavy rain of tear gas canisters fell on the crowd. The mobile water cannon started pushing us down the boulevard. This frontal attack succeeded in creating panic among protesters. To escape the suffocating atmosphere created by the thick clouds of tear gas, some demonstrators tried to find a way out by entering buildings or climbing fences and walls. Progressively, the cortège de tête retreated until reaching the intersection between the Boulevard Saint-Marcel and the Boulevard de l’Hôpital.

There, as police were still blocking the side of the boulevard leading to the train station—the closest and safest exit—some demonstrators decided to use the last option they had by retracing their steps. Unfortunately for them, as the trade unions were slowly entering the Boulevard Saint-Marcel, police started shooting tear gas into the boulevard to keep the crowd inside the area they had designated to attack the cortège de tête. People were now definitely trapped on two different boulevards between a rain of tear gas and police lines. As a result, the confrontations inside the kettle intensified: anarchists and other rebellious protesters answered the thick clouds of tear gas and the explosions of flash-bang grenades with a rain of projectiles, smashing windows and setting makeshift barricades on fire.

A line of riot police under a rain of projectiles.

Near Place d’Italie, protesters attacked the main police station.

As the situation became more and more explosive—and due to the insistence of some demonstrators—police finally agreed to release the pressure by letting some demonstrators exit the demonstration via the main police checkpoints located on the Boulevard de l’Hôpital. Hundreds seized the occasion to escape the trap. However, once outside the main police perimeter, many people were still determined to stay in the streets. Little by little, a large crowd began to gather behind police lines. Understanding that the situation could quickly escalate, police started to push the protesters back with a series of charges and volleys of tear gas canisters.

Behind the police checkpoint, the rest of the traditional May Day procession—trade unions included—was allowed to pursue its course towards Place d’Italie, as the authorities claimed to have regained control over the situation. As hundreds of determined people were walking down the Boulevard de l’Hôpital towards the train station and the Austerlitz bridge, a wildcat demonstration got underway. Following a quick sprint to escape the police line that tried to block our progress, the crowd crossed the bridge.

A demonstrator escaping police arrest at Place d’Italie.

After some people erected makeshift barricades, a trailer on a construction site was set on fire near the Austerlitz bridge during a short wildcat action.

Once we reached the other side of the Seine river, people built several makeshift barricades to block traffic and set the trailer of a construction site on fire. For the first time since the morning, we felt that we had finally succeeded in outmaneuvering the trap set by the authorities. Unfortunately, this feeling didn’t last long, as the first brigades of police officers on motorcycles armed with LBD-40 launchers showed up soon after. Following several attempts to escape them, recognizing that the situation was becoming more and more dangerous, the raging crowd dispersed near Bastille.

Later that evening, hundreds of people answered the call to gather at the Place de la Contrescarpe in order to celebrate the one year anniversary of the “Benalla case.” This case started on May Day 2018, when Alexandre Benalla—then one of Macron’s security officers—received authorization from the executive to assist police forces on the ground. Dressed as a member of the BAC—in plain clothes with a helmet and the traditional orange police armband—he threatened and brutally arrested several individuals inside the Jardin des Plantes and at the Place de la Contrescarpe. Informed of these events, the government covered up the case and protected Benalla. In July 2018, after a long investigation, some journalists revealed the true identity of Benalla. Since then, the “Benalla case” continues to embarrass the current government, as more and more dark secrets and revelations surface.

Alexandre Benalla—wearing a police helmet and a grey hoodie—at Place de la Contrescarpe on May Day 2018.

Police near the Place de la Contrescarpe where demonstrators gathered to celebrate the one-year anniversary of the “Benalla case.”

The Aftermath: Police Lies and Violence Come to Light

May Day 2019 is over. Altogether, at least 40,000 people demonstrated in Paris despite the heavy-handed strategy of repression. The massive wave of “violent radicals” that authorities were expecting did not show up, as only between “800 and 1000 people came to square off,” according to official sources. At the close of this long day of confrontations, 315 individuals were in custody and numerous demonstrators had been injured. On the national scale, authorities only mention 24 demonstrators and 14 police officers injured. Obviously, these figures are brazenly inaccurate.

Overall, the authorities were satisfied with the results of the strategies they employed on May Day 2019. Due to the large number of preventive searches and identification checks (almost 20,000) and the reduced amount of property destruction compared to May Day 2018, the new state approach seemed to have borne fruit. “Our strategy paid off, especially the fact of preventing the formation of black bloc groups by hitting them hard as soon as they tried to form,” said someone from the Paris Prefecture, while another police source added: “We were very mobile, very offensive, very powerful. […] At no time during the day did we lose the upper hand.”

Eager to celebrate its victory and reassert its hegemony, the government initiated a heavy media campaign to discredit people who took part in street confrontations. However, the results of this campaign took them by surprise.

A perfect example of the new strategy of repression implemented by the French government: police are ordered to frontally attack demonstrators and engage in hand-to-hand fights.

First, as thousands of protesters were pushed back by police forces on the Boulevard de l’Hôpital, Christophe Castaner—the Minister of the Interior aka “the first cop of France”—apparently received reports that a group of potential “breakers” had entered the Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital and were attacking it. Without thinking twice, he stated: “Here, at the Pitié-Salpêtrière, a hospital was attacked. Its health care personnel were assaulted. And a policeman in charge of protecting the building was injured. Unwavering support for our police forces: they are the pride of the Republic.” Later that day, every corporate media relayed the story about the arrest of the thirty-two “intruders,” as well as the fact that they were all in custody for “participating in a gathering with the objective of committing property destruction or violence.”

While corporate media did not even investigate this far-fetched claim from the Minister of the Interior, we knew that this sensational story of “rioters attacking a hospital” was a pure fabrication intended to discredit demonstrators and their actions—as this exact same strategy had already been used against us during the movement against the Loi travail. A call for anonymous testimonies appeared on a radical publishing platform. This initiative, as well as several “fact checks” by traditional newspapers, enabled us to share our own side of the story in order to deconstruct the deceitful propaganda of the state.

Contrary to the lies of Christophe Castaner, you can see here what happened at the Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital: as police were filling the Boulevard de l’Hôpital with tear gas in order to push back the leading procession, people began to panic. Some individuals located in front of the hospital succeeded in breaking the lock and opening the fences. People rushed into the courtyard in order to escape the tear gas. As police entered the hospital and began charging them, thirty-two terrified people attempted to find shelter in the closest building—where the intensive care unit was located.

As you can see in this video taken from inside the intensive care unit, demonstrators did not “assault health care personnel” or “attack” the hospital. As one hospital worker rightly said in the video: “It is the fault of the CRS (Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité, the French riot police): they came, they kettled [the demonstrators], the only way out was here.” Regarding the injured police officer mentioned by Castaner in his tweet, a cobblestone hit him in the head during clashes that took place about forty minutes after the events at the hospital.

Following the revelations that the Minister of the Interior had intentionally lied about the events at the Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital, the government had no choice except to step back. Under pressure, Christophe Castaner was forced to explain his behavior in a press conference. Hardly ashamed to be caught lying to the public, he said at that press conference that the scandal regarding his words was nothing but an “absurd polemic.” In the end, the thirty-two comrades were released and the charges against them dropped.

Police brutality on May Day.

Then, while the authorities were proudly talking about the effectiveness of their new law enforcement approach for maintaining social order, several videos spread online showing police brutality during the demonstration. Among them: a riot police officer throwing a cobblestone at demonstrators; a member of the BAC violating an arrestee by shoving his telescopic baton inside his pants; a police officer in riot gear slapping a demonstrator in the face; and other footage of policemen strangling, brutalizing, and tripping demonstrators.

Footage of police strangling, brutalizing, and tripping demonstrators on May Day, including one officer hurling a paving stone at demonstrators.

In the end, the French government, which had expected to carry the day via a strong media campaign to discredit riots and rebellious demonstrators, ended up having to deal with two major controversies that could potentially further weaken its legitimacy and image, especially in the current explosive political and social context. Perhaps, in the end, the government has not emerged victorious from the May Day events after all.

The burning rage of a dying planet.

Reflections

The suffocating and oppressive demonstration of May Day 2019 is now behind us. However, we should not simply move forward to the next day of action without analyzing what happened in the streets that day. If the leading procession is to reinvent itself and stay unpredictable, we must reflect on the events of the day and study the strategies and decisions made on the field. Otherwise, we will remain trapped in the role assigned by authorities, as well as of our own self-satisfied and ritualized form of superficial radicalism. As there is always room for improvement, we present several thoughts that we hope will contribute to refining our strategies for actions and riots to come.

1984? No, 2019.

The law enforcement strategy used by authorities during May Day 2019 made quite an impression. The massive—and almost unprecedented—police presence deployed all around the course of the traditional afternoon demonstration put the most terrifying dystopian novels to shame. All day long, numerous police checkpoints, searches, patrols, frontal attacks and incursions, and gratuitously brutal arrests confirmed the ruthlessness of the new law enforcement strategy. From now on, the authorities aim to crush social movements and political unrest by any means necessary, even if this means injuring even more demonstrators than they have already. They aim to establish a state of fear through intentional police brutality and intense legal repression, including new legislation to give law enforcement a free hand during demonstrations, such as the Loi “anti-casseurs”. All this already started before the yellow vest movement. The authoritarian shift of the French government is well under way and undeniable.

The authorities are willing to crush any form of rebellion and unrest—but to do so, they have had to adapt their modus operandi in accordance with the tactics and strategies of the cortège de tête. The intensification of police checkpoints and searches before demonstrations enables them to arrest potential rioters and to seize equipment of all kinds. They hope that, if they do this, these people won’t participate in street confrontations—which, if we follow their logic, should weaken the leading procession. Another aspect of the cortège de tête that the authorities have clearly understood is that one of its major assets is its mobility and speed. Therefore, what better way to control the offensive crowd than to lead it into a trap in which every single exit is blocked by police lines? Then the authorities will know our route and our potential objectives precisely. They can decide to kettle everyone whenever they choose, then engage in hand-to-hand combat and arrest more people. And if some people succeed in escaping from the kettle to start wildcat actions—as we saw during May Day 2019—the authorities can send their motorcycle brigades to disperse everyone.

Members of the BRAV (Brigades for the Suppression of Violent Action) carrying out an incursion into the crowd to make arrests.

All this confirms that we need to reconsider our tactics and strategies. Willingly entering the trap set by the authorities has prevented us from opening new breaches and unleashing our destructive creativity in joyful and spontaneous actions. In the end, on May Day, we were exactly where the police wanted us to be, inside their perimeter, and this enabled them to contain and brutally repress us.

The difficulty in preparing for events like May Day in Paris is that, as they attract thousands and thousands of individuals, it is not easy to plan secretly in a way that will reach most people. Once a crowd decides to play by the rules set by authorities, it faces tremendous disadvantages. Considering that authorities are willing to injure even more demonstrators if they have to, we should take this issue seriously.

On numerous occasions, participants in the yellow vest movement have demonstrated their capacity and determination by remaining outside police perimeters. This enabled everyone to engage in intense street confrontations and property destruction, sometimes without even seeing police for minutes or hours. Obviously, with the new Police Prefect and the new strategy of repression, the situation has evolved. However, we continue to believe that a strategy of decentralization is the most efficient solution, as police can’t hope to control many wildcat demonstrations of hundreds of demonstrators if they take place at the same time in many different locations. The question is—how do we deal with the new extremely mobile police units? So far, they are the ones that threaten spontaneous marches and actions.

As in any strategy, there is a weak point. The objective now must be to find this weak point in order to thwart the government’s new strategy of repression.

We must respond to every attack with new strategic innovations.

If nothing else, the sheer number of people in the streets for May Day proves that Macron’s political announcements did not pacify anyone or resolve the ongoing political crisis. Far from it. Despite the massive police presence, the trap set by authorities, and the clear warnings that the government broadcast before May Day, people’s determination and rage remains unbreakable. Thousands and thousands of yellow vesters answered the invitation sent by radicals to join a leading procession that comprised considerably more than half of the entire afternoon demonstration—confirming the decline of trade unions as a tool of political pacification. The trap set by authorities didn’t stop demonstrators from engaging in impressive and courageous street confrontations with police, nor from starting wildcat actions outside of the perimeter.

In the end, despite the fierce repression, anarchists and other autonomous rebels succeeded in putting their personal touch on this May Day. The fact that the French government claimed victory on May Day even as images of massive confrontations and property destruction circulated is itself revealing. It shows how desperately the current government needs to preserve the image that it maintains hegemony, as the political context remains explosive and all efforts to construct a new social peace have utterly failed.

Alongside the indomitable solidarity participants in the cortège de tête expressed in response to the cowardly attacks of the police, all this confirms that, against the odds, we can still remain ungovernable and open up new horizons.

“The rich started it!”

Further Reading

For additional information and accounts on May Day 2019, we recommend this communiqué written by the Legal group of the Coordination against repression of Paris and the Île-de-France region, as well as this article.