In this second installment of our coverage of the 2018 G20 summit, our international correspondents report on the political and cultural events leading up to the summit. China has given Argentina a considerable amount of military equipment with which to brutalize and potentially mass-murder people in Buenos Aires if they interfere with the state agenda of totalitarian control during the G20 meetings. Meanwhile, organizers have announced the schedule for a week of resistance. The lines are drawn.

Saturday, November 17

Day of “Militant Peronism”

This day marks the return of Juan Domingo Perón on November 17, 1972 after 17 years of exile in Franco’s Spain; the date is still celebrated annually by the Peronist movement in Argentina. Traditionally, there is a large rally with numerous speeches. This year, it took place in the stadium of a local football club. The motto is: Unidos o Dominados, “united or dominated.” The dominant theme is President Macri’s austerity budget package imposed by the IMF and his “necessary replacement—at the latest, by the 2019 elections.” Naturally, of course, by the Peronists.

But what is this “unity,” exactly? Some Peronists in the Senate voted for the budget package; they were called “traitors” at the rally. But also, the powerful Peronist trade union federation CGT is conducting a dialogue with a high-ranking IMF representative, while other parts of the Peronist movement support the protests and are also calling for a protest against the G20 summit. These call themselves “Peronismo popular”; they are left-oriented and still able to mobilize masses of people onto the streets. In addition, a large part of the Porteños (the urban residents of Buenos Aires) feel connected to Peronism; in many cases, this loyalty has been passed down across multiple generations. This describes a considerable portion of modern and cosmopolitan urban society in Buenos Aires.

Between Nazi Exiles and Left-Wing Guerrillas

What most Perón fans don’t know—or have suppressed in their memories—is that after World War II, Perón opened Argentina to thousands of high-ranking Nazi officials. Above all, he wanted them to help him establish his own aviation industry, including the secret continuation of the Nazi missile program. Some ended up in Peron’s secret service; others set up “Mercedes-Benz Argentina” with his support, where demonstrably massive quantities of dirty Nazi money were laundered. The Holocaust co-organizer Eichmann found employment there, along with many other Nazis.

At the same time, Perón implemented extensive social programs aimed at the poorer sections of the population and promoted culture, education, and civil rights, including the introduction of women’s suffrage. In foreign policy, he was emphatically anti-American, but in domestic policy, he fought communists and brought the previously heterogeneous trade unions into line. He controlled the press through state-controlled paper quotas. When the previously flourishing economy went downhill, Perón—though the “legitimately elected president”—was expelled by a military putsch in 1955 with the backing of influential entrepreneurs, the church, bourgeois intellectuals, and the CIA.

A permanent change of government was established under the control of the military, the economy continued to decline, and social tensions increased. In the 1960s, armed groups throughout Latin America began the “revolutionary struggle,” including the so-called Montoneros in Argentina. They simultaneously referred to the successful Cuban revolution, Peronism, and the anti-imperialist struggle. Their tactics ranged from organizing soup kitchens in the poor neighborhoods to carrying out armed raids on military facilities. Not least, this movement helped create the pressure that led to Perón’s return in 1972. He died in 1974 and his third wife, Isabell Perón, took power. The military overthrew her in 1976.

A military dictatorship ensued, lasting until 1983, which particularly persecuted the Montoneros with an immense bloodshed.

Sunday, November 18

La Criatura: The “Performative Counter Summit”

The two-day festival La Criatura was about “thinking up other ways to make politics.” As the organizers put it:

“The politics we make is old. We cannot close our eyes to what is happening in Brazil because it is a global trend.”

The event took place in one of the numerous and largely self-organized cultural centers of Buenos Aires, organized by the Asociación “CRIA”—Creando Redes Independientes y Artisticas. In South America, “crias” also means Lama—“young animals.”

All kinds of workshops, many of an artistic nature, took place in various adjoining rooms. A long table was set up in the large hall in mockery of the G20 summit. Here, people gradually took seats for the presentation of the various thematic forums.

First, there was a short introduction by a woman dressed up as a monster with snake hands. She read a pithy text:

“A predator devours the world. It is able to destroy countries and nations, cultures and peoples, change nature genetically, turn forests into deserts, undermine the seas and drill into mountains to extract the last mineral fragment. This predator wants to leave us nothing, a humanity freed from everything. In defiance of this devastating scene, there are other herds of monstrous creatures that reinvent themselves in the face of this plundering, that create counter-pedagogy, building utopias and errant becomings.”

Then they presented a historical outline of former summit protests—beginning in the early 1990s, when the anti-globalization movement slowly developed, and passing from the 2001 G8 summit in Genoa to Mar de la Plata (about 400 km south of Buenos Aires), where in 2005, the Organization of American States met in the face of massive protests. They emphasized that over the years, resistance has shifted more and more to the global South and that a specific expression was found there, which still has to be expanded.

This was followed by an impressive lecture by a Mapuche, who told the story of his people and of growing oppression and repression, but also of the resistance and the expressiveness of the Mapuches, which is gaining more and more international attention through social media. In the end, he emphasized amid applause that the struggle of the Mapuche nation cannot be solved solely by granting them their land. Rather, their struggle represents a future model for how to inhabit the earth and they are convinced that it is time to develop alternatives.

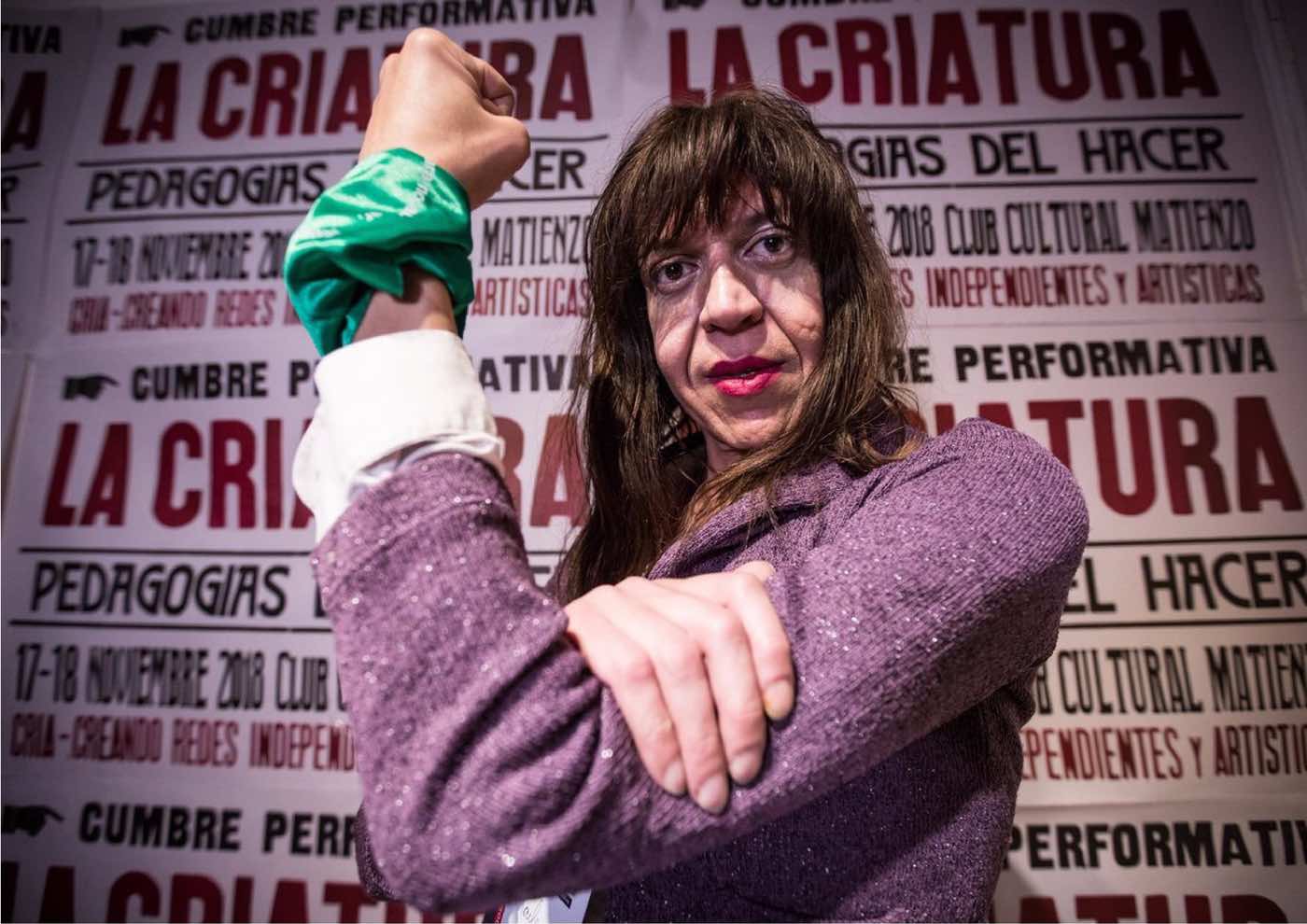

There followed are several contributions by representatives of the feminist movement who presented their progress and the growing resistance against patriarchy, stressing that all the different forms of resistance to the capitalist patriarchal system must be given the same importance. They referred to the immense mobilizations of the last few months, in which huge numbers of people took to the streets against the ban on abortion, among other things.

Numerous other contributions followed—for example, a presentation by the representative of the Senegalese Association in Argentina on the growing importance of migration in the face of extensive exploitation and oppression in the regions of the global South, above all in Africa.

Finally, the conference took a position against the current criminalization of the resistance and called for participation in the week of resistance to the G20 from November 25 to December 1.

Monday, November 19

The Schedule of the Week of Protest

The program describes almost 60 public events. Most of them are discussions, workshops, or lectures—many within the framework of the alternative (counter) summit—but there are also a number of public actions. At this point in time, ten days before the summit, not all the events have been announced; this was no different at previous summit protests.

The schedule impressively documents the diversity and internationalism of the upcoming counter-events and protests. It is available online in English here and in Castellano here.

Argentine security personnel test military-grade crowd repression equipment from China, preparing to attempt to impose a future of brutal violence on humanity.