I’ve never liked the part of the story when the mentor figure dies and the young heroes say they aren’t ready to go it alone, that they still need her. I’ve never liked it because it felt clichéd and because I want to see intergenerational struggle better represented in fiction.

Today I don’t like that part of the story because… I don’t feel ready.

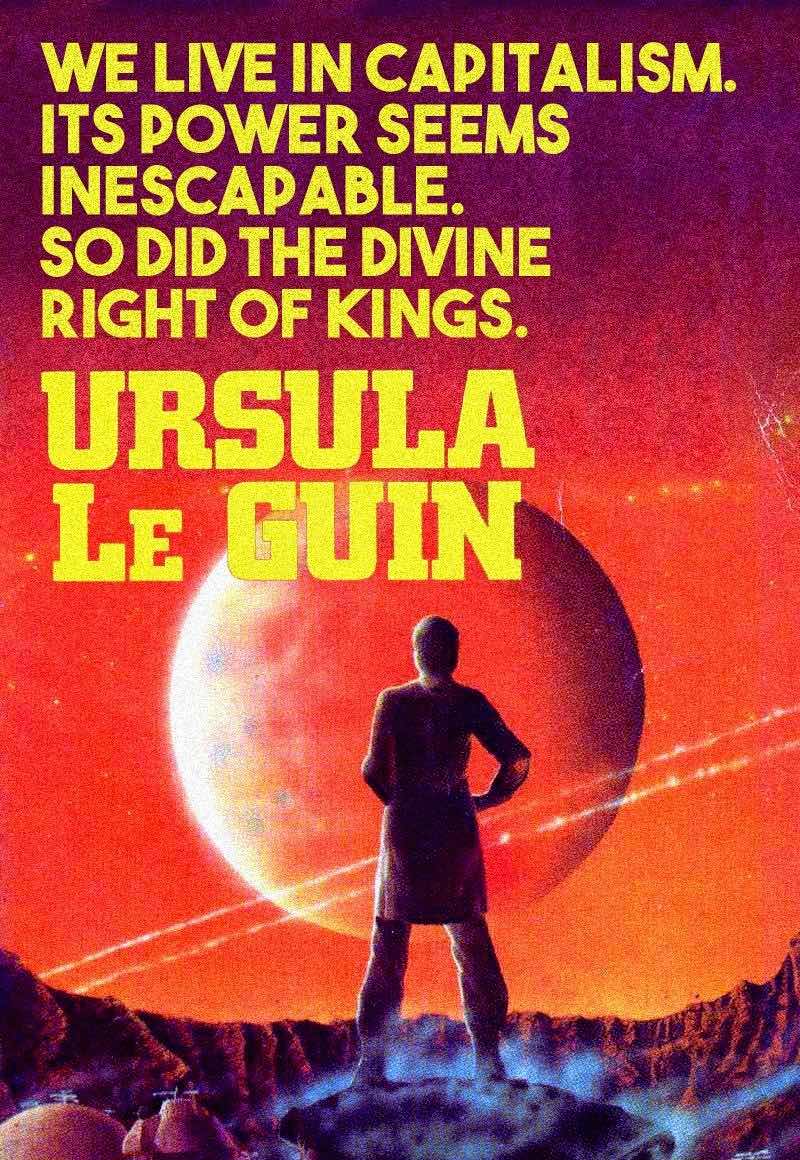

Last week, I lived in the same world as Ursula Le Guin, a grandmaster of science fiction who accepted awards by decrying capitalism and seemed, with every breath, to speak of the better worlds we can create. On Monday, January 22, 2018, she passed away. She was 88 years old and she knew it was coming, and of course my sorrow is for myself and my own loss and not for a woman who, after a lifetime of good work fighting for what she believed, died loved.

It’s also a sorrow, though, to have lost one of the most brilliant anarchists the world has ever known. Especially now, as we start into the hard times she said were coming.

To be clear, Ursula Le Guin didn’t, as I understand it, call herself an anarchist. I asked her about this. She told me that she didn’t call herself an anarchist because she didn’t feel that she deserved to—she didn’t do enough. I asked her if it was OK for us to call her one. She said she’d be honored.

Ursula, I promise you, the honor is ours.

When I think about anarchist fiction, the first story that comes into my head is a simple one, called “Ile Forest,” which appeared in Le Guin’s 1976 collection Orsinian Tales. The narrative is framed by two men discussing the nature of crime and law. One suggests that some crimes are simply unforgivable. The other refutes it. Murder, surely, argues the one, that isn’t for self-defense, is unforgivable.

The chief narrator of the story then goes on to relate a story of a murder—a vile one, a misogynist one—that leaves you with both discomfort and with the awareness that no, in that particular case, there would be no justice in seeking vengeance or legal repercussions against the murderer.

In a few thousand words, without even trying, she undermines the reader’s faith in both codified legal systems and vigilante justice.

It wasn’t that Le Guin carried her politics into her work. It’s that the same spirit animated both her writing and her politics. In her 2015 blog post “Utopiyin, Utopiyang” she writes:

“The kind of thinking we are, at last, beginning to do about how to change the goals of human domination and unlimited growth to those of human adaptability and long-term survival is a shift from yang to yin, and so involves acceptance of impermanence and imperfection, a patience with uncertainty and the makeshift, a friendship with water, darkness, and the earth.”

That’s the anarchist spirit that animated her work. Anarchism, as I see it, is about seeking a better world while accepting impermanence and imperfection.

I spend a lot of my time thinking about, reading about, and learning from others about how fiction can engage with politics. I don’t want to put Le Guin on a pedestal—she herself, in perfect form, refused to let people call her or her work genius—but no one wrote political fiction with the same flair for well-told book-length metaphor as she did.

The easiest book for me to talk about is The Dispossessed, because it’s the most widely-read anarchist utopian novel in the English language. When an anarchist like Le Guin writes her utopia, it’s explicitly “an ambiguous utopia.” It says so, right on the cover. It’s the story of an anarchist scientist at odds with his own anarchist society and the stifling social conventions that can grow up in the place of laws. It’s a story of that anarchist society, far from perfect, favorably compared to both capitalism and state communism. It’s also a story about how beautiful monogamous relationships can be once they’re not compulsory. When the anarcho-curious ask me for a novel to read that explores anarchism, I don’t always suggest it, since the anarchist world represented is so bleak (my go to, more often that not, is Starhawk’s The Fifth Sacred Thing). It’s too anarchist of a text to serve as propaganda.

Le Guin was also a pacifist. I’m not one myself, but I respect her position on the matter. I think it was that pacifism that helped her write about violent anti-colonial struggle with as much nuance as she did in The Word for World is Forest. There’s an inherent kindness in the violence in that book, which pits an indigenous alien race (the inspiration for the Ewoks of Star Wars, incidentally, in case you needed more proof that anarchists invent everything) against human invaders. The glory of struggle is muted, rendered realistically. The glory of it is as dangerous as the actual violence, as it should be.

Le Guin and other authors blew open the doors of what science fiction could be, presenting social sciences as equal to hard sciences. Her novel The Left Hand of Darkness is about people who alternate between male and female. As I understand it, it was an unprecedented work when it came out in 1969. I didn’t love it the way that I’ve loved some of her other books, but I’m not sure I can imagine what the world would look like if it had never been written. I can’t point to another work that has done more to seed the idea that gender can and should be fluid. It’s possible that my life as a non-binary trans woman would be completely different had she not written that book.

The Lathe of Heaven is psychedelic fiction at its finest and a parable of the power held by artists and those who imagine other worlds. Presciently, it explores a society destroyed by global warming.

For the luckier kids of my generation, Le Guin’s fantasy series, Earthsea, filled the role that Harry Potter has for people younger than me. I wish I’d read it as a kid, though I don’t regret how often I read The Hobbit. In the world of Earthsea, the villains who threaten the world are aspects of the heroes who have to save it.

The words Le Guin has written that have meant the most to me, though, are her short stories. If you want to understand why so many people cried to hear of her death, read “The Ones Who Walked Away from Omelas.” It is, simply, and I don’t say this hyperbolically, perfect. It’s short, and beautiful, and it’s exactly the kind of story that can change the world.

I haven’t read all of Le Guin’s books, and I have to admit, I’m glad about that today. I’m glad that there are more of her stories waiting for me.

The Left Hand of Darkness.

When I was a baby anarchist, I wanted to know what anarchism had to do with fiction. I get most of my ideas by talking to smart people, so I set out to ask smart people my question. I wrote Ursula Le Guin a letter and sent it to her PO Box. She emailed me back and I interviewed her for what I thought would be a zine.

That zine became my first book, which started what has since become both my career and, presumably, my life’s work. She had literally nothing to gain by helping me, encouraging me, and lending her tremendous social credibility to my project. I like to think she was excited to talk explicitly about anarchism in a way she didn’t often get to, but frankly I might be projecting my hopes onto her.

I think of her kindness to me as an act of solidarity between two people fighting the same fight.

That’s a big part of why I’ve cried so much since her death.

Later into that same book project, I started to ask myself why I cared so much why this or that author identified as an anarchist or worked for anarchist projects. I’ve always been less concerned with the boundaries of our ideology and more interested in words and deeds that encourage freethinking, autonomous individuals who act cooperatively. Whether or not Le Guin calls herself (or lets us call her) an anarchist doesn’t change what she’s written or how she’s impacted the world. Many of the best and most beneficial writers, activists, and friends I know or know of don’t call themselves anarchists, and that doesn’t change the love I have for them. I’ve also never been particularly excited about celebrity culture, idol worship, or really just fame as a concept.

Yet it mattered to me—still matters to me—that Le Guin was an anarchist.

I finally came to terms with why I care so much. I care because it means that those stories that have meant so much to me were written by someone with whom I’m aligned on a lot of very specific hopes and dreams. I care because I can use her own words to eviscerate anyone who attempts to recuperate her into some other camp—say, liberal capitalist or state communist—and use her celebrity to promote causes she did not support or actively opposed. I care because the accomplishments of anarchists have been written out of history time and time again, and Le Guin is famous for some very specific and undeniable achievements that will be very hard to erase. Maybe it’s hero worship. Maybe it’s basking in reflected light. I don’t know. I just know that she makes me proud to be an anarchist.

I don’t have a lot of heroes. Most of my favorite writers, I aspire to be their peers. Ursula Le Guin was a hero. She mentored me without knowing it. She encouraged my writing both directly, by telling me she was excited for what I would write, and indirectly, by telling me why writing is worthwhile and also with her book on writing Steering the Craft.

Right now, I’m thinking about her words on the importance of words. As I step back from most organizing, I think about what she told me a decade ago:

“Activist anarchists always hope I might be an activist, but I think they realize that I would be a lousy one, and let me go back to writing what I write.”

But she knew that words alone weren’t enough. Art is part of social change, but it isn’t anywhere near the whole of it. Le Guin did thankless work, too, attending demonstrations and stuffing envelopes for whatever organization could use her help. It’s that dichotomy that makes her my hero. I want everyone to leave me to my writing and not expect me to organize, but I want to be useful in other ways too.

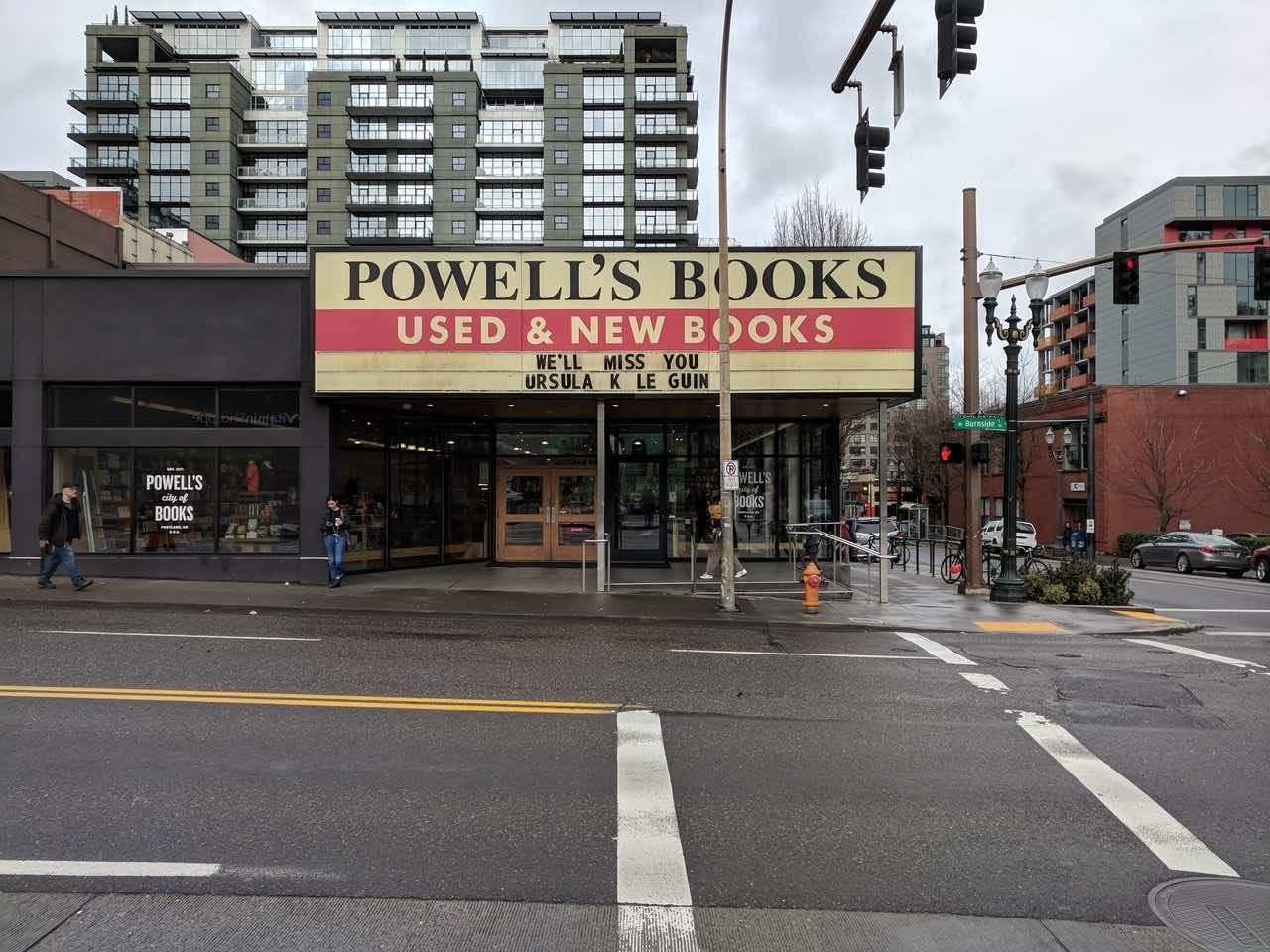

Powell’s Books remembers.

Last night, three of us exchanged Signal messages about her passing. “It’s up to us now,” we said. “We have to work harder without her now,” we said. Signal messages are like whispers sometimes. In the dead of night, we say the things that scare us.

In 2014, Le Guin told the world:

“Hard times are coming, when we’ll be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now, can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine real grounds for hope. We’ll need writers who can remember freedom—poets, visionaries—realists of a larger reality.”

I don’t feel ready, but no one ever does. The truth is: we are ready. There are writers who remember freedom. Maybe more now than there have ever been. There are stories that need to be told, and we are telling them. Walidah Imarisha will tell them. adrienne maree brown will tell them. Laurie Penny will tell them. Nisi Shawl will tell them. Cory Doctorow, Jules Bentley, Mimi Mondal, Lewis Shiner, Rebecca Campbell, Nick Mamatas, Evan Peterson, Alba Roja, Simon Jacobs, and more people than I can know or count will tell them.1

All of us will tell them, to each other, by whatever means. We’ll remember freedom. Maybe we’ll even get there.

The author speaking with Ursula Le Guin at Powell’s Books in 2010.

-

This list is not to imply any specific political affiliation of the authors, only to tell you about writers who, I believe, remember freedom. ↩