The perilous politics of militant anti-fascism defined 2017 for the anarchist movement in the United States. The story in the Bay Area mirrors that of the country at large. It’s a narrative full of tragedies, setbacks, and repression, ultimately concluding with a fragile victory. Yet there was no guarantee it would turn out this way: only a few months ago, it seemed likely we would be starting 2018 amid the nightmare of a rapidly metastasizing fascist street movement. What can anti-fascists around the world learn from what happened in Berkeley? To answer this question, we have to back up and tell the story in full.

Fascists chose Berkeley, California as the center stage for their attempt to get a movement off the ground. The advantage shifted back and forth between fascists and anti-fascists as both sides maneuvered to draw more allies into the fight. Riding on the coattails of Trump’s campaign and exploiting the blind spots of liberal “free speech” politics, fascists gained momentum until anti-fascists were able to use these victories against them, drawing together an unprecedented mobilization. As we begin a new year, anti-fascist networks in the Bay Area are stronger than ever. Participants in anti-fascist struggle enjoy a hard-earned legitimacy in the eyes of many activists and communities targeted by the far right. By contrast, the far-right movement that gained strength throughout 2016 and the first half of 2017 has imploded. For the time being, the popular mobilization they sought to manifest has been thwarted. The events in the Bay Area offer an instructive example of the threat posed by contemporary far-right coalition building—and how we can defend our communities against it.

2016: A New Era Begins

Clashes escalate outside a Trump Rally in San Jose on June 2, 2016.

The clashes between far-right forces and anti-fascists that gripped Berkeley for much of 2017 were the climax of a sequence of events that began a year earlier. On February 27, 2016, Klansmen in the Southern California city of Anaheim stabbed three anti-racists who were protesting a Ku Klux Klan rally against “illegal immigration and Muslims.” The rhetoric of the Klan echoed the same vulgar nationalism that the Trump campaign was broadcasting. Under the banner of the alt-right, many white supremacist and fascist groups began to use the campaign as an umbrella under which to mobilize and recruit. They aimed to build an ideologically diverse social movement that could unite various far-right tendencies within the millions mobilized by Trump. A reactionary wave had steadily grown across the country in the last years of the Obama era. The combination of continued economic stagnation, proliferating anti-police uprisings of Black and Brown people, and rapidly changing norms related to gender identity and sexuality had spawned a violent backlash. This was the wave that Trump rode upon and his campaign had broken open the floodgates.

Trump rallies became increasingly contentious in cities such as Chicago (March 11) and Pittsburgh (April 13) as protesters held counterdemonstrations to confront these open displays of bigotry. On April 28, 2016, small-scale rioting erupted outside a Trump rally in the southern California city of Costa Mesa. The next day, in the city of Burlingame near San Francisco, large crowds disrupted Trump’s appearance at the convention of the California Republican Party, leading to scuffles with police.

Days later, on May 6, a newly-formed fascist youth organization, Identity Evropa (IE) held their first demonstration on the other side of the Bay—an ominous portent of things to come. This initial experiment was organized by IE as a “safe space” on the UC Berkeley campus to promote “white nationalist” ideas and their particular style of business-casual far-right activism. Inspired by European identitarian movements, IE worked to coopt the rhetoric of liberal identity politics and use the contradictions inherent in those politics to build a new white power movement. Their strategy was part of a larger effort across the alt-right to recruit young people and legitimize white supremacist organizing as an acceptable form of public activism. The rally brought together Nathan Damigo, the founder of IE, with members of the Berkeley College Republicans and the alt-right ideologist Richard Spencer, who flew in from out of town to attend. Although the event was barely noticed, the participants declared it a success and a first step towards building a new nationalist street movement.

The most violent clashes outside a Trump campaign rally unfolded in San Jose on June 2. A handful of experienced activists attended the counterdemonstration, but the vast majority of protesters were angry young people of color from the South Bay unaffiliated with any organization. The police response was slow and confused; clashes between the crowds raged into the evening. Photos of people punching and chasing Trump supporters spread online, leading to calls from many on the far right for revenge.

On June 26, over 400 anti-racists and anti-fascists converged on the state capitol in Sacramento to shut down a rally called for by the Traditionalist Workers Party, a neo-Nazi organization based in the Midwest. The rally was initially billed as an “anti-antifa” rally organized in response to the protests at recent Trump events. It was also an attempt to build bridges across various far-right tendencies. The majority of the anti-fascists wore black masks; other crews represented various leftist cliques. Together, they successfully prevented the rally from ever starting. Comrades held the capitol steps, chasing off scattered groups of Nazis and alt-right activists.

About three hours after the counterdemonstration began, two dozen members of the Golden State Skins, geared up in bandanas and shields decorated with white power symbols and the Traditionalist Workers Party emblem, suddenly appeared on the far side of the capitol and attacked the crowd from behind. Six comrades were stabbed, some repeatedly in the torso, while riot police watched impassively. Nearly all those targeted in the attack were either Black or transgender. Miraculously, all of them survived.

Members of the Golden State Skins attempt to kill anti-fascists in Sacramento on June 26, 2016.

After the bloody clash, many people urgently felt the need for a new politics of militant anti-fascism. Over the preceding decades, one rarely heard the term antifa among anarchist and anti-capitalist movements in the Bay Area. Previous generations of anti-fascist and Anti-Racist Action (ARA) organizing in Northern California were largely situated within subcultural contexts. Much of the work these activists accomplished in the 1980s and ’90s focused on kicking Nazis out of punk and hardcore scenes.

The events in Sacramento helped usher in rapid transformations of the local anarchist movement. A network of comrades formed Northern California Anti-Racist Action (NOCARA) to research and document increasing fascist activity across the region. Other crews linked up to practice self-defense and hone their analysis in the rapidly shifting political terrain. Antifa symbols—the two flags and the three arrows—quickly became as ubiquitous as the circle A in the Bay Area anarchist milieu. Some lamented this as a retreat from struggles against capitalism and the police into a purely defensive strategy singularly focused on combating fringe elements of the far right. But the majority understood it as a logical step necessitated by the rising tide of fascist activity around the country and world. They aimed to situate an anti-fascist position as a single component of the larger struggles against capitalism, patriarchy, and white supremacy that comrades had been engaged in for years. Most participants had cut their teeth in various rebellions and movements in the Bay area over the preceding decade, including Occupy Oakland and Black Lives Matter. They saw antifa as a form of community self defense against the violent reaction to those struggles for collective liberation. Many were also eager to use anti-fascism as a means to open a new front against white supremacy and the state.

On November 9, the night after Trump’s electoral victory shook the world, a march of thousands followed by the most intense night of rioting in recent memory took place in downtown Oakland. Fires broke out in the Chamber of Commerce, the Federal Building, and the construction site of the new Uber building. Angry crowds of thousands fought police with bottles, fireworks, and even Molotov cocktails as banks were smashed, barricades blocked major streets, and tear gas filled the air. Other cities across the country also saw significant unrest; rowdy protests in Portland, Oregon lasted for days.

This made 2016 the eighth year in a row that serious rioting took place in Oakland. 2017 would end that pattern. The locus of street conflict in the Bay was about to shift up the road to the neighboring college town of Berkeley.

Starting the Year off with a Bang

Thousands swarm San Francisco International Airport to protest Trump’s “Muslim Ban” on January 28, 2017.

The tone for 2017 was set on the cold morning of January 20 in Washington DC. As mainstream media pundits nervously reiterated the importance of a peaceful transition of power, a black bloc of hundreds chanting “Black Lives Matter!” took the streets to disrupt Trump’s inauguration. In the course of the day, hundreds were arrested, a person in a black mask punched Richard Spencer as he tried to explain alt-right meme Pepe the Frog, and video of the incident went viral.

That same evening in Seattle, Milo Yiannopolous spoke on the University of Washington campus as part of his “Dangerous Faggot” tour. Milo had made a name for himself over the previous year peddling misogyny and Islamophobia in his role as tech editor for Breitbart News under the mentorship of Steve Bannon. He had become a leading spokesperson for the alt-right auxiliary known as the alt-lite. The logic behind his tour was similar to IE’s strategy of targeting liberal university enclaves using a provocative model of far-right activism rebranded for a millennial audience.

Hundreds turned out to oppose Milo’s talk in Seattle. As scuffles unfolded outside the building, a Trump supporter drew a concealed handgun and shot Joshua Dukes, a member of the Industrial Workers of the World, in the stomach. Milo continued his talk unconcernedly as the critically injured Dukes was rushed to emergency care. Fortunately, he survived, though he spent weeks in the hospital.

Despite the unprecedented degree of tension in the air, Oakland was quiet on J20. A few small marches, mostly departing from high school walkouts, crossed downtown. But by nightfall, the rainy streets were empty; hundreds of riot police deployed for the anticipated unrest packed up their gear to go home. This new year was not going to play out along familiar lines.

The next day, millions across the country marched against Trump in the Women’s Marches, many of them wearing pink “pussy hats.” Oakland was the location of the main Bay Area march and tens of thousands walked through downtown in a staid and orderly display of disapproval. Later that week, Trump signed executive order 13769 suspending US refugee resettlement programs and banning entry for all citizens of seven predominantly Muslim countries, including people with valid visas. By the following afternoon, a spontaneous and unorganized national mobilization was underway as tens of thousands swarmed the international terminals of every major airport in the country to oppose the “Muslim ban.” Loud marches and blockades continued for two days inside San Francisco International Airport.

In many ways, the airport protests marked the high point of the year in terms of mass action that undermined the regime’s ability to carry out its agenda. The mobilization immediately disrupted the implementation of the executive order and provided momentum to challenge it in the courts, where legal maneuvers continued throughout the rest of the year. Nevertheless, the protests did not coalesce into a more sustained sequence.

The Real Dangerous Faggots

Sproul Plaza outside Milo’s cancelled event on February 1, 2017.

On February 1, Milo arrived in Berkeley for the final talk of his tour, hosted by the Berkeley College Republicans. Days earlier, his talk in nearby UC Davis had been successfully disrupted by student protesters; all eyes were now on UC Berkeley campus.

Berkeley is an upper-middle-class city of 120,000 bordering Oakland, defined by the prestigious flagship campus of the University of California system that sits adjacent to downtown. The city’s history as a national hub of countercultural movements and far-left political activism stretches back to the early 1960s. In 1964, student radicals returning from the Freedom Summer campaign in Mississippi set up tables on campus to distribute literature about the growing Civil Rights movement. The administration cracked down on their activities, sparking a wave of civil disobedience that came to be known as the Free Speech Movement (FSM). In many ways, it was the beginning of the student activism against racism and imperialism that proliferated across the country throughout the 1960s. Yet by the turn of the new millennium, Berkeley could be more accurately described as a hotbed of liberalism, not radicalism. The legacy of the FSM had been successfully coopted and rewritten by the university administration for their prospective student marketing materials. Students can now sip cappuccinos as they study for exams in the Free Speech Movement Café on campus.

On the south edge of campus sits Sproul Plaza, site of some of the most important demonstrations of the FSM and subsequent waves of activism. As the sun set on Sproul that Thursday evening, between two and three thousand students, faculty, and community members filled the plaza in a rally against Milo, the alt-right, and Trump. Layers of fencing surrounded the Martin Luther King Jr. Student Union as platoons of riot police watched the chanting crowd from the balconies of the building and the steps leading down to the plaza.

Milo’s talk was about to start. Despite the large protest, it appeared that the massive police presence would enable it to proceed without a hitch. Then a commotion on neighboring Bancroft Way drew the attention of the crowd. A black bloc of roughly 150, some carrying the anarchist black flag and others carrying the queer anarchist pink and black flag, had just appeared out of the neighborhood and was busy building a barricade across the main entrance to the student union’s parking garage. As the barricade caught fire, the bloc surged forward to join the thousands in Sproul.

The sound of explosions filled the air as fireworks screamed across the plaza at the riot cops, who hunkered down and retreated from their positions. Under cover of this barrage, masked crews attacked the fencing and quickly tore it apart. Thousands cheered. Police on the balconies unloaded rubber bullets and marker rounds into the crowd, but ultimately took cover as fireworks exploded around their heads. With the fencing gone, the crowd laid siege to the building and began smashing out its windows.

Anti-fascists rip down fences on UC Berkeley campus on February 1.

“The event is cancelled! Please go home!” screamed a desperate police captain over a megaphone as the crowd roared in celebration. A mobile light tower affixed to a generator was knocked over, bursting into flames two stories high. YG’s song “FDT” (Fuck Donald Trump) blasted from a mobile sound system as thousands danced around the burning pyre. Berkeley College Republicans emerging from the cancelled event were nailed with red paint bombs and members of the Proud Boys, the “Western Chauvinist” fraternal organization of the alt-lite, were beaten and chased away. Milo was escorted out a back door by his security detail and fled the city. A victory march spilled into the streets of downtown Berkeley, smashing every bank in its path. Milo’s tour bus was vandalized later that night in the parking lot of a Courtyard Marriot in nearby Fremont.

The cover of the next day’s New York Times read “Anarchists Vow to Halt Far Right’s Rise, With Violence if Needed” below an eerie photo of a hooded, stick-wielding street fighter in Berkeley. “Professional anarchists, thugs and paid protesters are proving the point of the millions of people who voted to MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN!” Trump tweeted that morning before threatening to withdraw federal funds from UC Berkeley if the university could not guarantee “free speech.” Milo had been stopped and militant anti-fascism was now a topic of national conversation.

But a confused controversy over free speech was just beginning. Liberals quickly fell into the trap set by the alt-right. UC Berkeley professor Robert Reich, who had been Secretary of Labor under Clinton, went so far as to embarrass himself by groundlessly claiming that “Yiannopoulos and Brietbart were in cahoots with the agitators, in order to lay the groundwork for a Trump crackdown.”

From organizing “white safe spaces” to pretending to represent a new free speech movement, the ascendant fascists understood that the hollow rhetoric of liberalism utilized by hacks like Reich could be weaponized against anyone opposed to white supremacy and patriarchy. Liberal enclaves were especially vulnerable to this strategy. They had become the chosen terrain on which 21st-century American fascism sought to step out of the internet to build a social movement in the streets.

Meanwhile, Milo’s days were numbered. Despite liberal commentators’ assertions that paying attention to Milo would only make him more powerful, Milo’s career imploded two weeks later. Under the intense scrutiny that followed his spectacular failure in Berkeley, a conservative social media account circulated footage of Milo condoning consensual sex between underage boys and older men. His invitation to speak at the American Conservative Union’s annual conference was quickly rescinded, as was his book deal with a major publisher. The next day, Milo was forced to resign from Breitbart. While emblematic of the rampant homophobia of the right, none of this had anything to do with his views on sex. After Berkeley, Milo appeared to be an increasingly controversial liability that conservatives could no longer risk associating with.

A Repulsive Rainbow of Reaction

Based Stickman (left) leads the goons on March 4.

While many celebrated Milo’s downfall as a blow to the alt-right, various far-right and fascist cliques hastened to take advantage of liberal confusion around the emerging free speech narrative.

On March 4, modest rallies in support of Trump occurred across the country. In the Bay Area, vague fliers appeared calling for a Trump Rally in downtown Berkeley’s Civic Center Park. There was considerable confusion among local anti-racists and anti-fascists over who had called for the rally. Many assumed it was just right-wing trolling that would never materialize in public. Nevertheless, various small crews of anarchists, members of the leftist clique By Any Means Necessary, anti-racist skinheads, and an assortment of unaffiliated young people converged on the park to oppose any attempt to hold the Saturday afternoon rally. They found a bizarre scene that few could have previously imagined.

A grotesque array of far-right forces had assembled from across the region to celebrate Trump and defend their ability to propagate various forms of nationalism, xenophobia, and misogyny. One man in fatigues and wraparound sunglasses carried a III% militia flag. Another man with a motorcycle helmet, tactical leg guards, and a kilt sported a pro-Pinochet shirt depicting leftists being thrown from helicopters to their deaths. Still another right-wing activist happily zipped around on his hoverboard while taking massive vape hits and live-streaming the event via his phone.

Many in the right-wing crowd were not white. The alliances being formed through public activism had brought together a range of fascist tendencies, some more interested in defending violent misogyny or building an ultra-libertarian capitalist future than promoting white power. MAGA hats and American flags were everywhere as the crowd of nearly 200 attempted to march into downtown Berkeley. Fistfights broke out, flags were used as weapons, and pepper spray filled the air as anti-fascists and others intervened to stop the march. A masked crew of queer anti-fascists dressed in pastels, calling themselves the Degenderettes, used bedazzled shields to defend people from the reactionary street fighters of this strange new right-wing social movement. Chaotic scuffles and brawls continued off and on for three hours.

Riot police located around the perimeter of the park made some targeted arrests; yet as in Sacramento, they largely avoided wading into the melee. Ten people were arrested altogether, from both sides of the fight. One of these was alt-right sympathizer and closet white supremacist Kyle Chapman. Chapman had helped form the vanguard of the right-wing brawlers throughout the day. He wore a helmet, goggles, and a respirator while carrying an American flag shield in one hand and a long stick as his weapon in the other. News of his arrest combined with footage of his assaults immediately elevated him to celebrity hero status within the online world of the alt-right and alt-lite. Memes of Chapman went viral under his new nickname, “Based Stick Man.”

Tactically speaking, there were no clear winners in Berkeley on March 4. But the nascent fascist street movement was energized and ready for more. Anti-fascists had underestimated the momentum of this new far-right alliance and were quickly trying to figure out how to play catch up.

On March 8, a group of revolutionary women and queer people in the Bay Area organized a “Gender Strike” action in San Francisco as part of the national “Women’s Strike” planned for International Women’s Day. The strike was called for as a means of moving beyond the liberal feminism of January’s massive Women’s Marches against Trump. From Gamergate trolling to Trump’s gloating over his sexual assaults, from the Proud Boy’s valorization of traditional family values to the bizarre right-wing alliance manifesting in the streets of Berkeley, the rise of neo-fascism was being fueled by misogynists intent on preserving and expanding patriarchal power relationships as much as it was being fueled by white supremacists. The organizers of the strike aimed to connect radical tendencies within the growing feminist movement with various anti-racist and anti-fascist struggles. Nearly a thousand protestors marched on the downtown Immigration and Customs Enforcement building in a demonstration of support for San Francisco’s sanctuary city status and solidarity with those targeted by surging xenophobia. An even larger crowd of Women’s Strike demonstrators marched in the streets of downtown Oakland that evening.

The Alt-Right Strikes Back

DIY Division (left) and other fascist thugs on April 15.

Two weeks later, on Saturday, March 25, over two thousand Trump supporters held a “Make America Great Again March” in the southern California city of Huntington Beach. Marching with the large crowd was an imposing squad of athletic white men clearly looking for a fight. These were members of the openly neo-Nazi group known as the DIY Division or the Rise Above Movement. When a handful of anti-fascists attempted to disrupt the march, this squad assaulted them and beat them into the beach sand. The fight was broken up and the anti-fascists fled as the crowd joined the DIY Division fighters in chanting “Pinochet!” and “You can’t run, you can’t hide, you’re gonna get a ’copter ride!”

To the horror of many in the Bay Area, another alt-right demonstration in Berkeley’s Civic Center Park was announced for April 15. Billed as a “Patriots’ Day Free Speech Rally,” it featured a lineup of speakers flying in from out of town. As the date grew closer, it became clear that every crypto-fascist wingnut, weekend militia member, millennial alt-right internet troll, alt-lite hipster, civic nationalist, and proud neo-Nazi from up and down the West Coast wanted to attend. The growing movement got a critical boost when the Oath Keepers militia announced two weeks ahead of time that they would be mobilizing from across the country under the name “Operation 1st Defenders” to protect the so-called “Free Speech Rally.” The Oath Keepers are a right-wing militia composed of active duty and veteran military and police officers that claims to have 35,000 members. The “operation” was to be led by Missouri chapter leader John Karriman, who oversaw the armed Oath Keeper operation to protect private property during the Ferguson uprising of 2014. Oath Keepers’ founder Stewart Rhodes would also be on the ground.

Bay Area anarchists met regularly during the weeks leading up to April 15 in hopes of developing some kind of strategic response to what was shaping up to be the most important showing yet of this far-right popular movement. Many comrades believed it was necessary to find a new approach in order to avoid spiraling into a violent conflict with an enemy that was better trained and better equipped than anti-fascists and anti-racists could ever be. A general plan was hashed out through meetings and assemblies that prioritized reaching out to the broader left and other activist circles in hopes of mobilizing large numbers of radicals who could drown out the alt-right rally while avoiding the kind of conflict that would strike the general public as a symmetrical clash between two extremist gangs. There was no specific call for a black bloc, which by this time had largely become synonymous with militant antifa tactics. Instead, fliers and posters began to circulate promoting a block party and cookout that could occupy the park at 10 am with large crowds listening to music and speakers before the “Free Speech Rally” started at noon.

Early in the morning of April 15, these plans collapsed disastrously. Dozens of Oath Keepers in tactical helmets and flak jackets established a defensive perimeter before sunrise alongside riot police who sectioned off various zones of the park with fencing and checkpoints. The organizer of the rally, the Oath Keepers, and the police had coordinated for weeks ahead of time.

Riot police surrounded comrades arriving in the park for the counter-demonstration; they confiscated trays of food for the cookout, musical instruments, flags, and signs. Police intervened to stop small scuffles as members of the DIY Division, in town for the rally from southern California, began to exchange taunts with anti-fascists. As noon approached, the 200 or 300 anarchists and anti-fascists who mobilized that day realized with terror that their attempts to reach out to other activists had fallen on deaf ears. They were alone, badly prepared for a fight, and were quickly becoming outnumbered by hundreds and hundreds of right-wing activists led by a street-fighting fascist vanguard and protected by a disciplined patriot militia.

Chaos erupted as the first speakers at the rally began to address the MAGA hat-wearing crowd inside the Oath Keeper perimeter. In a desperate attempt to give momentum to the demoralized and scattered anti-fascists, a crew with a mobile sound system in a street next to the park began blasting “FDT” to the cheers of many counterdemonstrators. People coalesced around the sound system and began moving around the edge of the rally. Some threw M80s into the park; others tried to breach the fencing. Most simply tried to stay together.

The police withdrew from the streets as fascist squads of young men emerged from within the rally to go on the offensive. Bloody fights broke out. Kyle Chapman, flanked by similarly geared-up brawlers including one man wearing a Spartan helmet, led a series of forays that split the crowd and left comrades bleeding on the ground. In one such attack, an anti-fascist was beaten by masked white men and dragged behind enemy lines to be stomped out. It was only through the intervention of the Oath Keepers and others functioning as “peace police” for the alt-right rally that the beating was interrupted; the comrade was shoved back across the skirmish line into the hands of friendly street medics. During the short pauses between clashes, fascists chugged milk and screamed as they pumped themselves up for the next assault.

Though outnumbered, anarchists and anti-fascists fought as best they could. Many Nazis and their sympathizers left that day bruised and bloodied. But the counterdemonstrators could barely hold their own against the fascist street fighters, let alone the Oath Keeper presence maintaining the interior perimeter. The rally of hundreds continued uninterrupted. As fatigue set in, the fascists made their move led by Chapman, members of DIY Division wearing their signature skull bandanas, and members of IE including Nathan Damigo. They blitzed the remaining counterdemonstrators and pushed them away from the park through a cloud of smoke bombs and into the side streets of downtown. A cautious retreat became a hasty run as the remaining anti-racists and anti-fascists were chased off the streets by Nazis. The fascists had won the third Battle of Berkeley.

Kyle Chapman, DIY Division (right), and Identity Evropa (far right) prepare for their final offensive of the day on April 15.

The fallout began immediately. Emboldened by the victory on the ground, an army of alt-right internet trolls on 4chan’s /pol thread and elsewhere began a doxxing witch hunt to identify all those who had opposed their shock troops in Berkeley. Within hours, they had used footage to identify a woman who had been brutally beaten by Damigo and others during the final assault of the day. Louise Rosealma had previously worked in porn; a misogynistic campaign of harassment against her began immediately. Oversized posters showing her naked next to Damigo’s smiling face with the words “I’d hit that” soon appeared on the streets of Berkeley.

Eric Clanton, a Diablo Valley College professor, became another doxxing target. Trolls claimed to have identified him as the masked anti-fascist caught on camera hitting a man in the head with a bike lock. The man on the receiving end of this blow wore a “Feminist Tears” button and had been seen attacking people alongside members of DIY Division throughout the battle. Eric received a slew of death threats; his online accounts were hacked and angry calls poured in to his employer that would eventually cost him his job.

On April 23, Kyle Chapman formalized his new role as leader of the militant vanguard of the alt-lite. He announced the formation of the “Fraternal Order of Alt Knights,” which was to function as the “tactical defensive arm of the Proud Boys.” Gavin McInnes, the founder of the Proud Boys and co-founder of Vice Magazine, had helped promote the “Free Speech Rally” and had welcomed Chapman to his show multiple times.

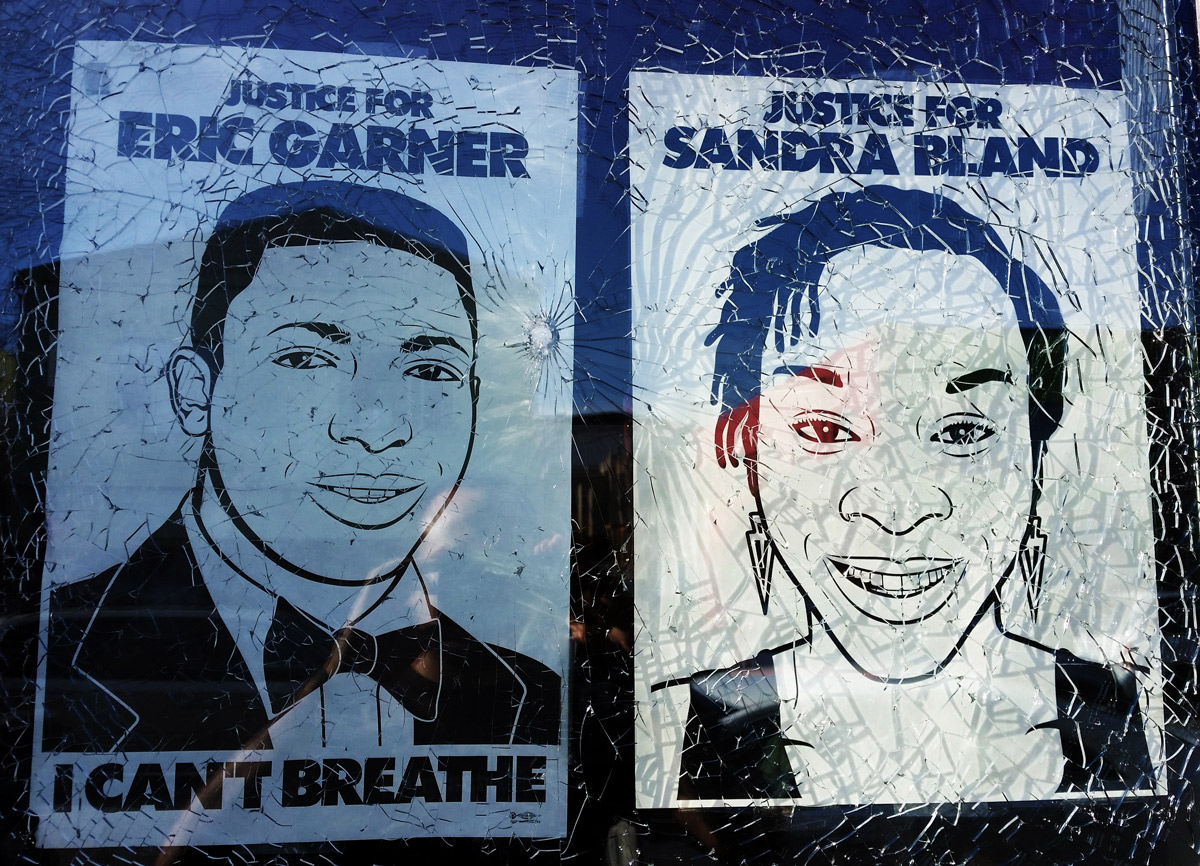

On April 27, McInnes joined another far-right rally in Berkeley’s Civic Center Park. The rally had been organized to coincide with Ann Coulter’s visit to UC Berkeley, which she cancelled at the last minute. Nonetheless, a large crowd of Trump supporters, fascists, and reactionary goons of various stripes flocked to Berkeley that day to get their piece of the action. They found themselves unopposed. Anarchists and anti-fascists were still licking their wounds; they had collectively decided to avoid a confrontation that could lead to another painful defeat like the fiasco of April 15. Later that night, the windows of the Black-owned Alchemy Collective Café were shot out. The café is located just blocks from Civic Center Park and its windows had been displaying posters in solidarity with Black Lives Matter and indigenous struggles.

A bullet hole in the window of the Alchemy Café on April 28, the day after another far-right rally in Berkeley.

Soon after, Eric Clanton was arrested by Berkeley Police in a house raid and charged with four counts of assault with a deadly weapon. During his interview at the police station, the detective expressed appreciation for 4chan’s /pol forum and informed Eric that “the internet did the work for us.” Eric’s case is pending and he faces years in prison.

The Turning Point

Solidarity demonstration with Charlottesville, August 12.

In chess, a player is said to “gain a tempo” when a successful move leaves their units in a more advantageous position while forcing their opponent to take a defensive move that wastes time and derails their strategy. The growing far-right social movement had gained a tempo at the expense of anti-fascists during spring 2017. The February victory against Milo and the alt-right in the first days of the Trump presidency had played an important role in disrupting attempts to normalize a dangerous new form of far-right public activity. Each attempt that fascists made to materialize in public risked extreme conflict. But anti-fascists’ success had helped to spawn an ugly reaction, which anarchists and other militant anti-fascists were unable to handle on their own.

There was nothing normalized or “respectable” about the armored and belligerent fascists who were determined to mobilize in Berkeley. Yet on a tactical level, they had proven they could leverage the necessary resources and foot soldiers to hold the streets in enemy territory. Anti-fascists had been forced into a downward spiral of responding to each new move without a strategy of their own. Paranoia, anxiety, and self-criticism characterized the local anarchist movement during late spring and early summer.

Yet important changes were underway. April 15 had caught the attention of many Bay Area activists who had remained outside the fray thus far. They were not convinced by the “free speech” rhetoric that had confused so many liberals. Militant anti-fascists had no interest in giving the state additional repressive powers to criminalize or censor speech. That was never what this struggle was about. Confronting fascist activity in the streets to stop its normalization and proliferation is a form of community self-defense. Increasing numbers of anti-racists understood this. Bay Area movement organizations such as the prison abolitionist organization Critical Resistance, the Arab Resource Organizing Committee, white ally anti-racist groups such as the Catalyst Project and the local chapter of Standing Up for Racial Justice (SURJ), and the Anti-Police Terror Project, who had played a leadership role in the local Black Lives Matter Movement, began to work with those who had been in the streets throughout the first half of the year to build a coordinated response.

Many of these groups had previously been at odds with anarchists. Some of the most bitter disputes revolved around issues of identity and representation within the various social movements of the preceding decade. Many anarchists rejected most forms of identity politics after seeing them used time and again by reformist leaders from marginalized groups to manage and pacify antagonistic movements. Liberal city officials, organizers of non-profits, and some social justice groups had regularly dismissed local anti-police and anti-capitalist rebellions in Oakland and elsewhere as the work of white anarchist “outside agitators” corrupting otherwise respectable movements led by people of color. This paternalistic and counter-insurrectionary narrative intentionally obscured the diversity of participants in these uprisings and erased their agency.

Things had begun to change in 2014 as anti-police rebellions spread across the country and the forces of racist reaction mobilized in response. Despite unresolved tensions, the anarchist movement played an important role in helping sustain struggles against white supremacy and other movements of oppressed people. Increasing numbers of activists and movement organizations supported the uprisings and understood the necessity of working together as part of a united anti-racist front. This convergence helped lay the groundwork for the unprecedented alliances that arose out of anti-fascist organizing.

The urgency of building these coalitions was tragically underscored on May 26, when a white supremacist cut the throats of three people who had intervened to stop him from harassing a young Muslim woman and her friend on a commuter train in Portland, Oregon. Two of the men died. The attacker, Jeremy Christian, had attended Free Speech Rallies organized by the Portland-based alt-lite group Patriot Prayer. At his arraignment, Christian yelled “Get out if you don’t like free speech… Leave this country if you hate our freedom—death to Antifa!”

A few weeks later, on June 10, thousands of anti-racists and anti-fascists in Seattle, Austin, New York, and elsewhere successfully mobilized against a day of anti-Muslim rallies attended by various groupings of neo-Nazis, militia members, alt-lite activists, and alt-right activists. During the Houston rally, scuffles between patriot militia members and an alt-right activist attempting to display openly fascist placards exposed growing cracks within the far-right alliance that had been built up through the spring.

On July 9, the growing anti-fascist network in the Bay Area held a packed forum in the Berkeley Senior Center, blocks from the site of the spring’s clashes. A range of speakers from the coalition helped educate the hundreds in attendance about the rising tide of white supremacist and fascist activity as well as the necessity of organizing for community self-defense. The crowd left the forum energized and eager to mobilize.

Another round of alt-right rallies was on the horizon. Many hoped that this time the response would be different. Patriot Prayer was calling for a rally in San Francisco on August 26 and a “Rally Against Marxism” was planned for the familiar battleground of Berkeley’s Civic Center Park on the following day. As the end of summer approached, fascists across the country made it clear they aimed to double down on their offensive. When a reporter for the New York Times asked Nathan Damigo about IE’s goals for UC Berkeley during the new school year, he laughed and responded, “We’ve got some plans.”

Before any of this could unfold, events on the other side of the country changed the course of history.

The first step of this renewed fascistic offensive was a mobilization in Charlottesville, Virginia promoted throughout the summer as a rally to “Unite the Right.” Building on their successes in targeting liberal enclaves over the previous months, alt-right leaders including Richard Spencer and Nathan Damigo aimed to take their movement-building to the next level by forging an alliance with Southern white supremacists under the banner of their rebranded far-right activism. Charlottesville is a liberal college town that, along with other cities throughout the South, had been planning to remove monuments celebrating the Confederacy. Spencer had previously led a small torch-lit rally in Charlottesville on May 13 to protest the proposed removal of a Robert E. Lee statue. The August 12 rally was supposed to be the turning point that could transform the young movement into an unstoppable reactionary force under the cover of the Trump regime.

On the evening of August 11, a surprise torch-lit demonstration on the University of Virginia campus attended by hundreds of white supremacists gave the impression that this turning point had arrived. Footage of fascists surrounding and attacking outnumbered anti-racist demonstrators at the foot of the statue of Thomas Jefferson on UVA campus spread around the country, provoking terror and urgency in equal measure.

Yet the following day turned out to be a historic disaster for the fascists. Anarchists and anti-fascists managed to interrupt the fascist rally, ultimately forcing police to declare it an unlawful assembly. The white supremacists retreating from the streets of Charlottesville knew that they had lost: their rally had been cancelled and the media was turning on them. They had failed to create a situation in which the volatile white resentment they drew on could be gratified by a successful show of force. That is why James Alex Fields, a member of the fascist organization Vanguard America, plowed his car into a crowd of anti-fascists that afternoon, killing Heather Heyer and grievously injuring 19 others.

Fascists had sought to attain the upper hand in the media narrative by presenting their opponents as enemies of free speech. But after “Unite the Right,” the alt-right was inextricably linked with images of armed Klansmen and Nazis carrying swastika flags. The connection between far-right activism and fascist murder had become too obvious for anyone to deny. Charlottesville immediately became a rallying cry for an emerging broad-based anti-fascist movement that mirrored the microcosm of cross-tendency networking unfolding that summer in the Bay Area.

The heroes of this story are the anarchists and other militant anti-fascists who put their bodies on the line to throw the “Unite the Right” rally into chaos. Grotesque images from the streets of Charlottesville on August 12 showed armored fascist street fighters engaged in combat with outnumbered anti-fascists. These delivered a fatal blow to the alt-right’s stated goal of using the rally to legitimize the popular movement they hoped to build. Anti-fascists had forced the alt-right to show its true face; the results were catastrophic for the movement’s future. If the brutality of April 15 forced the Bay Area to reconsider far-right propaganda about “free speech,” August 12 in Charlottesville did the same thing for the whole country.

Resistance movements in the Bay Area are always strongest when they are not alone. When rebellions in Oakland, Berkeley, or San Francisco are simply militant outliers or exceptions that prove the rule, they are ultimately isolated and neutralized. Comrades in the Bay are most effective when their actions are a reflection of what is happening elsewhere around the country. The events in Charlottesville kicked local anti-fascist coalition-building into high gear. Within hours of Heather’s murder, nearly a thousand anti-racists and anti-fascists gathered in downtown Oakland and marched to the 580 freeway, where they blocked all traffic and set off fireworks in a display of solidarity with comrades in Charlottesville. Many drivers waved and raised fists in support.

Solidarity with Charlottesville demonstration shuts blocks the 580 freeway in Oakland on August 12.

Over a hundred solidarity demonstrations took place around the world over the following days. Many targeted Confederate monuments in the South. On August 14, demonstrators in Durham, North Carolina pulled down a statue of a Confederate soldier. Meanwhile, the Three Percenters Militia, which had deployed fully-armed platoons as part of the Unite the Right rally, issued a national stand-down order stating, “We will not align ourselves with any type of racist group.” Infighting between various far-right tendencies blaming each other for the disaster reached a fever pitch.

The national discourse around militant anti-fascism that had begun in response to the events in DC on January 20 and Berkeley on February 2 shifted dramatically. After Charlottesville, anti-fascists were suddenly riding a tidal wave of support from the left and many liberals. Cornel West, who had attended the counterdemonstration with a contingent of clergy, pointedly stated on the August 14 episode of Democracy Now, “We would have been crushed like cockroaches if it were not for the anarchists and the anti-fascists.” Traditional conservative leaders such as Republican senators John McCain and Orin Hatch even lent tacit support to anti-fascists as they went on the offensive against Trump. Mitt Romney weighed in on August 15, tweeting, “One side is racist, bigoted, Nazi. The other opposes racism and bigotry. Morally different universes.” By August 18, Steve Bannon, the most powerful and visible face of neo-fascism within the Trump regime, was forced out of the administration in an apparent act of damage control responding to the growing crisis. Anti-fascists were once again in control of the tempo.

The Final Battle of Berkeley

Black Bloc helps settle the score in Berkeley, August 27.

Far-right activists from the Bay Area who had attended the Unite the Right rally returned home to find they had lost their jobs. Fascist podcast personality Johnny Monoxide was fired from his union electrician job in San Francisco after posters appeared at his workplace outing him as a white supremacist and neo-Nazi sympathizer. Cole White, who had assaulted people in Berkeley alongside Kyle Chapman and others throughout the year, was fired from a Berkeley hot dog stand after being outed by the @YesYoureRacist twitter account for attending the torch march.

By mid-August, a complex network of spokescouncils, coalition meetings, assemblies, and trainings were bringing together a diverse range of activist, left, and anarchist tendencies in the Bay on a nearly daily basis to prepare for the alt-right rallies of August 26 and 27. Honest conversations about how to allow for a diversity of tactics while respecting different risk levels and different vulnerabilities forged an unprecedented level of trust and solidarity. On August 19, in Boston, Massachusetts, over 40,000 counterdemonstrators confronted a few dozen alt-right activists and Trump supporters, including visiting alt-lite celebrity Kyle Chapman, who were attempting to host another “Free Speech Rally.” This was the largest demonstration against fascism and the alt-right in the US throughout 2017. It was another sign of the turning tides. In Laguna Beach, just down the coast from where 2000 Trump Supporters had marched with DIY Division in March, a small “America First” rally against immigration was vastly outnumbered by 2500 anti-fascists and anti-racists.

Morale was high among Bay Area anti-fascists and anti-racists as the weekend rallies approached. Local graffiti crews lent support, spreading a campaign of writing anti-Nazi and anti-Trump messages in cities around the region. Various local businesses announced that they would not serve alt-right rally attendees while opening their doors to offer spaces of refuge for anti-fascists. Calls to action emerged from almost every single Bay Area activist and movement organization. A common thread in many of these calls was a respect for different approaches to confronting fascism and a commitment to “not criminalize or denounce other protesters.”

Saturday’s alt-right demonstration was planned for San Francisco’s Crissy Field with the Golden Gate Bridge as a backdrop. On the eve of the rally, Patriot Prayer organizer Joey Gibson announced the event was cancelled due to safety concerns. Instead, Patriot Prayer planned to hold a press conference across the city in Alamo Square Park.

Despite the apparent change of plans, over a thousand anti-racists and anti-fascists converged on Alamo Square the next day. Among them were members of the ILWU and the IBEW, Johnny Monoxide’s union. This labor contingent had mobilized to support the counterdemonstration and to make it clear that fascists would not be tolerated in their ranks.

They found the park completely fenced off and occupied by hundreds of riot police, but no sign of Patriot Prayer or other far-right activists. Gibson and others including Kyle Chapman had retreated to an apartment down the coast in the city of Pacifica, from which they issued a statement over Facebook blaming city leaders and antifa for their own failure to hold a rally. It was becoming clear that their movement was imploding and the real obstacle to their rally was the potential of an embarrassingly low turnout. A colorful and celebratory victory march took the streets of San Francisco, making its way towards the Mission district. Throughout the rest of the day, anywhere far-right activists were sighted, counterdemonstrators swarmed the location and chased them off. Late in the day, Gibson and a handful of others made a surprise photo-op appearance in Crissy Field. A large crowd of counterdemonstrators chased them to their cars and they fled.

The “No to Marxism in America” rally planned for Berkeley on Sunday at 1 pm was also cancelled by organizer Amber Cummings. Nevertheless, the anti-racist and anti-fascist mobilization showed no signs of slowing down and Berkeley police were preparing for the worst. Berkeley City Council had passed a series of emergency ordinances giving the police special powers to set up multiple security perimeters around Civic Center Park and to ban items ranging from picket signs to masks. Over 400 police officers stood ready in and around the park on that sunny morning.

Two major rallies against the alt-right and against white supremacy were planned for the day in Berkeley. The first was organized by a coalition including local chapters of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), campus student groups, and a range of unions. It began across downtown on the edge of the UC Berkeley campus at 10:30. By 11, thousands were in attendance.

Other smaller groups went straight to Civic Center Park, where numbers had been growing since early in the day. As noon approached, nearly a thousand anti-racists and anti-fascists milled about between concrete barriers and various layers of fencing as hundreds of riot police monitored the scene under an increasingly hot sun. Screaming and shoving erupted multiple times as scattered Trump supporters and alt-right adherents attempted to enter the park. Some punches were thrown; this time, in contrast to March 4 and April 15, squads of riot police responded immediately to break up the fights and make arrests. The few anti-fascists who arrived with their faces concealed were tackled by police and arrested for violating the emergency ordinances.

Riot police face off against thousands of anti-fascists in Civic Center Park on August 27.

A few blocks away, in Ohlone Park, the second rally, organized by the local chapter of SURJ along with other anti-racist groups, was just beginning. Thousands were preparing to march. The call to action for this mobilization explicitly asserted the necessity of confronting fascists with a diversity of tactics and asked all attendees to respect those utilizing more confrontational forms of resistance. As a sound truck began leading the crowd towards Civic Center Park, a black bloc of nearly 100, many wearing helmets and protective gear, emerged from a side street ahead lighting off flares and chanting “¡Todos Somos Antifascistas!” The bloc parted for the sound truck and joined the front of the march to the cheers of the crowd. There were now nearly 10,000 anti-fascists of all stripes on the streets of Berkeley.

The black bloc doubled in size as it marched. Riot police standing guard around the Berkeley Police station on the corner of Civic Center Park looked on in dismay as the bloc led the crowd right up to the edge of the outer security perimeter. Tensions quickly escalated as riot police formed a skirmish line along the perimeter facing off against the bloc. One cop attempted to grab a masked comrade’s shield; others forced him back. Another cop fired a rubber bullet into the bloc as masked comrades with shields moved to the front line. A speaker on the sound truck announced that those wanting to help form a defensive line could move forward with the black bloc and all others could step back across the street to the steps of the old City Hall to hold space. Dozens of large shields were distributed from others in the crowd to those on the “defensive line.” Riot police began strapping on gas masks and aiming their various projectile weapons at the crowd. A major clash between two well-prepared sides was about to break out.

Anarchists hold the defensive line with shields on August 27.

Suddenly, the cops pulled back. All riot police in Civic Center Park had been ordered to withdraw to side streets in order to avoid instigating a riot. The crowd surged forward over the concrete barriers with the black bloc at the front chanting “Black Lives Matter!” Thousands flooded into the park, openly disobeying the emergency ordinances. Many chanted “Whose Park? Our Park!”

When Joey Gibson and his crew of patriots arrived minutes later, the crowd cheered on militant anti-fascists as they chased the pathetic showing of alt-lite reactionaries down a side street, where police fired smoke grenades to end the confrontation. Back in the park, the mood was jubilant and calm. Many applauded the black bloc and thanked them for keeping the crowd safe from neo-Nazis and white supremacists, who had been spotted leaving the area after seeing the size of the anti-fascist crowd.

A second march from the morning rally arrived in the park and members of the DSA, carrying red flags, gave high fives to members of the black bloc carrying black flags. Clergy members made speeches and sang from the sound truck as people dismantled more of the police barriers. After an hour and a half of holding the park, the decision was made to leave together. The clashes had been minimal, the police had been forced to back down, and no one had sustained serious injuries: this was undeniably a massive victory.

A diverse yet united front of 10,000 anti-fascists had finally settled the score in Berkeley. As the black bloc joined the march out of Civic Center Park, they chanted “This is for Charlottesville!”

The top story of next morning’s San Francisco Chronicle began,

“An army of anarchists in black clothing and masks routed a small group of right-wing demonstrators who had gathered in a Berkeley park Sunday to rail against the city’s famed progressive politics, driving them out—sometimes violently—while overwhelming a huge contingent of police officers.”

What this description left out was the coordination and solidarity with thousands of other demonstrators that had allowed this “army of anarchists” to take back Civic Center Park without any significant clashes. That was the important story of the day. But the narrative emerging from the anti-fascist victory in Berkeley looked very different to those who were not there. Corporate media described anarchists and militant anti-fascists as hijacking an otherwise peaceful movement. These media outlets focused on a few scuffles that broke out with Gibson’s crew and some other reactionaries, including a father-son duo, wearing a Trump shirt and Pinochet shirt respectively, who had entered the park and pepper sprayed the crowd at random.

A father-son duo, wearing a Trump shirt and a Pinochet shirt, are pushed out of the park after pepper spraying the crowd on August 27.

August 27 was a relatively relaxed and celebratory day in the streets of Berkeley. Yet from the outside, national media outlets that had ignored the much uglier violence of April 15 painted it as a disturbing street battle between extremist gangs. The short-lived window of mainstream support for militant anti-fascism that had opened after the tragedy in Charlottesville was now closing. As long as anti-fascists were understood only as victims of white supremacist violence, liberals could support them. Yet as soon as those wearing black gained the upper hand, they were described as a threat to the status quo—potentially as dangerous as the Nazis themselves.

“The violent actions of people calling themselves antifa in Berkeley this weekend deserve unequivocal condemnation, and the perpetrators should be arrested and prosecuted,” read a quickly-issued statement from Democrat house minority leader Nancy Pelosi. “I think we should classify them as a gang,” said Berkeley Mayor Jesse Arreguin. “They come dressed in uniforms. They have weapons, almost like a militia and I think we need to think about that in terms of our law enforcement approach.”

However, the diverse coalition that had been forged over the summer stood its ground. “We have no regrets for how they left our city. We do not want white supremacists in our city,” said Pastor Michael McBride in a press conference on the steps of the old City Hall the following day. “We don’t apologize for any of it,” said Tur-Ha Ak of the Anti-Police Terror Project. “We have a right and an obligation to self-defense, period.” A declaration of victory published by the Catalyst Project stated that it was “hard to convey how meaningful it was, after Charlottesville, for a very disciplined group of antifa activists to offer protection to the crowd from both police and white supremacists.”

Within activist, left, and anarchist circles in the Bay Area, there was no infighting after August 27. The unprecedented levels of trust and coordination that had developed between various groups held firm. Compared with the intense sectarian conflict that followed the spectacular demonstrations of the Occupy movement and the various waves of anti-police rebellions in the Bay, the revolutionary solidarity of 2017 was unheard of. This was the real victory of the Battles of Berkeley.

Make Total Decomposition

Milo exits the stage escorted by his $800,000 police security detail on September 25.

The emergent fascist social movement that had grown throughout the first half of 2017 was now in ruins. Anti-fascist victories in Charlottesville, Boston, and Berkeley had shattered reactionary dreams of a far-right popular movement coalescing in Trump’s first year. The various tendencies that had converged under the banner of the alt-right were running for cover and turning on each other.

In a desperate attempt to give a new lift to his falling star, Milo had been hyping his triumphant return to Berkeley for a so-called “Free Speech Week” from September 25-28 in collaboration with an offshoot of the College Republicans calling itself the Berkeley Patriot. Together, they promised days of provocative events on and around campus featuring far-right speakers including Ann Coulter, Blackwater founder Eric Prince, and even Steve Bannon. The anti-fascist coalition in the Bay braced for another wave of reactionary posturing and violence. On the eve of Free Speech Week, hundreds took to the streets of Berkeley as part of the No Hate in the Bay march. As the march ended without serious incident in a rally at Sproul Plaza, Chelsea Manning made a surprise speech in a show of support for anti-fascists.

Over the preceding days, signs of infighting among the organizers of Free Speech Week had become increasingly apparent as venues changed, plans were cancelled without explanation, and the media received contradictory messages from Milo’s PR team, student Republican leaders, and campus administrators. In the end, Free Speech Week fizzled completely, reinforcing the increasing irrelevance of Milo and the alt-lite. On Sunday, September 25, about 60 far-right activists and Milo fans stood in an empty Sproul Plaza listening to Milo talk for 20 minutes while waiting in line to get his autograph. They were surrounded by a massive militarized police presence that cost the university $800,000.

BAMN and the Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP) turned out about 100 counter demonstrators who made some noise outside the police perimeter. But most anti-fascists stayed away. Milo had already been beaten back in February and the fascist reaction to that victory had now also been overcome.

Within less than hour, it was all over and Milo fled the city once again. Small groups of alt-right activists who had flown in for Free Speech Week tried their best to build momentum throughout the rest of the week. One group stood outside the RCP’s Berkeley bookstore and banged on its windows. Another rallied outside the Black Student Union on campus. Joey Gibson and Patriot Prayer even held a small demonstration in People’s Park. Students organized a rally that Monday to protest the fascists’ presence on their campus; militant anti-fascists were on edge all week as they monitored each of these events. Yet none of this activity enabled the insurgent far right to reach critical mass again. Evaluated as publicity stunts, recruitment tools, and tactical advances, all the events surrounding Free Speech Week were pathetic failures. They were barely noticed and did nothing to change the balance of forces.

On October 12, alt-right and white supremacist sympathizers within the Berkeley College Republicans were deposed in an internal coup that gave more traditional conservatives more control of the student organization. Bitter infighting within the group continued throughout the rest of the semester, reflecting similar splits on the state level within College Republicans. Identity Evropa also faced unstable leadership following the collapse of the strategy of targeting liberal university enclaves, which they had pioneered on Berkeley campus in May 2016. Nathan Damigo resigned as IE’s leader on August 27 following his disastrous participation in the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville. He was replaced by Elliott Kline, who was then replaced at the end of November by Patrick Casey. In an interview in which he announced his plans to move away from the damaged brand of the alt-right and to stop attempting to hold any kind of large public demonstrations, Casey stated, “We can’t go into these liberal areas and essentially repeat what happened with Unite the Right.” Reflecting on his movement’s shortcomings, the Daily Stormer’s Andrew Anglin admitted that “large rallies on public property, where we know there is going to be confrontation with antifa, are not a good idea.”

Meanwhile, in southern California, on October 21, former member of Kyle Chapman’s Fraternal Order of Alt Knights and fellow alt-lite leader Johnny Benitez accused Chapman of not being racist enough and personally profiting off of his “activism,” leading to a fist fight between the two men at the California Republican Party’s 2017 convention in the Anaheim Marriott. The next day, Chapman led a squad of Proud Boys to disrupt a Laguna Beach Benghazi rally organized by Benitez. Both men accused each other of being Federal informants and infiltrators. Fully 150 riot police were deployed to keep the quarreling factions apart. Later that week, Chapman found himself in yet another messy public split with Florida fascist August Invictus who had previously been FOAK’s second in command. The alt-right meltdown was in full swing.

The core leadership of the fascistic far right continued desperately attempting to regain all they had lost. Patriot Prayer returned to Berkeley yet again for another tiny and insignificant rally in People’s Park in November. In December, Kyle Chapman promoted a march through San Francisco aimed at using the acquittal of the man charged with Kate Steinle’s death to protest the city’s “sanctuary city” status. Other far-right activists in Portland, Oregon, Austin, Texas, and elsewhere across the country attempted to use this same issue to mobilize the crowds that had stood beside them earlier in the year. Yet by December, their numbers were minuscule; in most cases, they found themselves overwhelmed by anti-fascist counterdemonstrations.

Nowhere was this clearer than in DC on December 3, when Richard Spencer, Matthew Heimbach of the Traditionalist Worker’s Party, former IE leader Elliott Kline, and other fascist leaders attempted to hold a rally. They were forced to cancel their march when less than 20 people showed up. They had failed to reignite the momentum that neo-Nazis and white supremacists rode on in 2016 and early 2017. By the end of the year, their movement was in total decomposition.

Solidarity Is Our Most Powerful Weapon

The August 27 black bloc marches in front of a sign printed and distributed by the city of Berkeley.

The alt-right has been defeated. The convergence of fascist and white supremacist tendencies under this rebranded far-right umbrella has been successfully disrupted, cutting off the core leadership from the base of Trump supporters from which they sought to draw power. Militant anti-fascists who took action in Berkeley, Charlottesville, and dozens of other cities across the country should be proud of the role they played in achieving this victory.

It is important to emphasize that this was not accomplished through a militaristic application of force. During the darkest days of the spring, when the alt-right mobilizations in Berkeley were at their strongest, it was not certain that even the largest of contemporary black blocs could have defeated the array of fascistic forces prepared to do battle. What tipped the scales, ultimately leading to the Nazis’ downfall, was the strength of solidarity between various anarchist, left, and activist groups committed to combatting white supremacy, patriarchy, and fascism with a wide range of tactics. As anti-fascist networks expanded and grew increasingly resilient, the ideologically heterogeneous networks of the far right imploded. The alt-lite turned on the alt-right, the civic nationalists turned on the ethno-nationalists, the patriot militias turned on the neo-Nazis, and the average Trump supporter who had dabbled in this growing movement was left confused and demoralized.

Yet the struggle against fascist and reactionary forces in the United States during the Trump era is just beginning.

There is no going back to a time before the stabbings, doxxing, Pinochet shirts, Pepe memes, torch-lit marches, and murder. Movements struggling for collective liberation must remain hardened and ready to face down whatever future fascist mutations rear their ugly heads from the cesspool of the far right. This is especially true for the anarchist movement in the United States, as anarchists have stuck our necks out further than almost anyone else to combat the rise of the alt-right. We cannot lower our guard; comrades will have to continue prioritizing individual and community self-defense for the foreseeable future. Many of these radicalized fascists will seek to exploit future crises to jumpstart their movement-building in new and unexpected ways. Other far-right activists will likely attempt to gain positions of power within law enforcement and other security agencies. Lone wolf attacks and other manifestations of far-right violence will almost certainly continue.

So we must remain on high alert. But if the threat of an imminent far-right popular movement with a fascist vanguard continues to recede, the politics of militant anti-fascism can evolve. This is what happens when we win.

Anarchist projects and initiatives can once again set their sights on the foundations of white supremacy, patriarchy, and capitalism. Some comrades can work to develop a revolutionary anti-fascist tendency that builds on the momentum of recent years. Others can take what they have learned from this sequence and refocus on advancing the struggles they have always been a part of.

Either way, anarchists and other militant anti-fascists are starting 2018 in a much more advantageous position than we held a year ago. The diverse networks of affinity and solidarity that turned the tide in 2017 will remain vital to the safety and resilience of everyone engaged in these dangerous activities.

At the same time, it must not be forgotten that fascists took advantage of the contradictions inherent in liberalism and the elitism of liberal enclaves to gain strength in 2016 and 2017. We must not water down anti-fascism via “popular front” politics until it becomes nothing more than a defense of liberal capitalism. We have to defend ourselves against co-optation as well as fascist agitation. The victories of 2017 have afforded us a brief opening to catch our breath and reaffirm the profoundly radical nature of our struggle for collective liberation. Imaginative revolutionaries must now lead new offensives on their own terms that bring us all closer to the world we wish to build.

Some Bay Area Antagonists January 2018

Taking the Park on August 27.