In dominant American discourse, white people are always the protagonists. Their problems and dilemmas, pleasures and pain, are treated as everyone’s primary concern. Even if you are not included in this narrative, you’re forced to reckon with it. While we anarchists would like to see a world in which no character is a caricature, in which people are not divided by race and only take delight in our differences, we are all currently obliged to pay attention to the problems of white people because, in their pain, they frequently lash out at those they perceive as their enemies. The opioid crisis is a prime example.

In an interview on National Public Radio, author Margaret Talbot describes a scene she witnessed at a softball practice in West Virginia:

“There were a bunch of middle school-age girls sitting on the ground comforting each other and crying, there were two little kids running around crying and screaming, and there were a lot of adults trying to help them and escort them away from the scene because two parents who had come to their daughter’s practice, a man and a woman, had both overdosed simultaneously and were lying on the field about six feet apart and in obvious need of resuscitation. Their two little younger children who had come with them were trying to get them to wake up. So Michael and his colleague were able to revive the parents using Narcan, which is the antidote to opioid overdoses—reverses them. But as is increasingly the case, it took several doses to revive them because they had probably had heroin that was cut with something stronger, possibly fentanyl. And so this was the scene that was witnessed by many people in this community who were at this softball practice on an afternoon in March.”

Some of those adult witnesses, Talbot says, were encouraging the EMTs to let the parents die. This inhumanity is shocking; it’s no mystery why people like the ones in this story are trying to get high. Few people feel like their lives are worth much these days; constant low-level stress over money, family, relationships, social disorder, health, and work are features of everyone’s lives. When you’re poor, and perhaps socially isolated, those things compound. Poverty is only occasionally dramatic or joyful; mostly, it’s crushingly boring and stressful. If you are prescribed pain medication because of an injury or chronic pain, the euphoria and floating freedom may be the best you’ve felt in years. This is how most people now start their opioid addictions.

In the 1990s, US doctors were reconsidering their beliefs about pain. Recognizing the toll that constant, low-level pain can take on the body—much like the effect of poverty upon the spirit—doctors began to prescribe pain medication more freely, believing that being free from pain might speed recovery, as well as being a boon in itself. Pharmaceutical companies told doctors that their latest pain medications were not likely to be addictive.

This claim is true for some—some people can take opioids for a couple of days after surgery and then switch to over-the-counter medicines without a hitch. But opioids hit other people’s brains differently: they experience intense pleasure and comfort, and after a couple of weeks of ease, going off the medication can feel unbearably bleak. So people kept going back for more—and, eventually, word began to circulate about which doctors would freely prescribe pain medications. Some of these offices were the frequently-exposéd, cynically-motivated “pill farms”; others just trusted their patients. Pain is pain, the doctors reasoned, and addiction is not a sin; is it really so bad to prescribe people what they need to feel OK in the world? What is the line between Adderall and speed, Oxycontin and heroin? Only legitimacy. For people who were not comfortable thinking of themselves as criminals, it felt more possible to exaggerate to a doctor than to buy heroin on the corner.

As word spread about the accessibility of these opioid pills, heroin dealers saw their market slipping away. Cartels in Mexico, Guatemala, and other countries took notice, and started producing heroin so pure that it could be cut much more, producing a larger amount of product that could be sold for less. They also began cutting it with different chemicals, which made it far more potent and potentially deadly; and, of course, cutting heroin to sell on the black market is not an exact science.

When the government finally started tightening regulations for prescribing opioids and raiding pill farms, millions of addicts were left desperate, and turned at last to explicitly illegal drugs, which were now more affordable than ever—and far more dangerous. While rates of opioid and heroin addiction are not actually higher than they used to be, the rate of people dying from overdoses has skyrocketed. The doses people are used to taking may be five times as potent as before. Surely no one wants to get high at their kids’ soccer practice: what they want is to feel normal rather than ravenous for a fix, able to cheer their kids on, so they fix a hit before they arrive… but sometimes, instead of enabling them to function, the medicine knocks them out.

Some of the victims of the overdose epidemic.

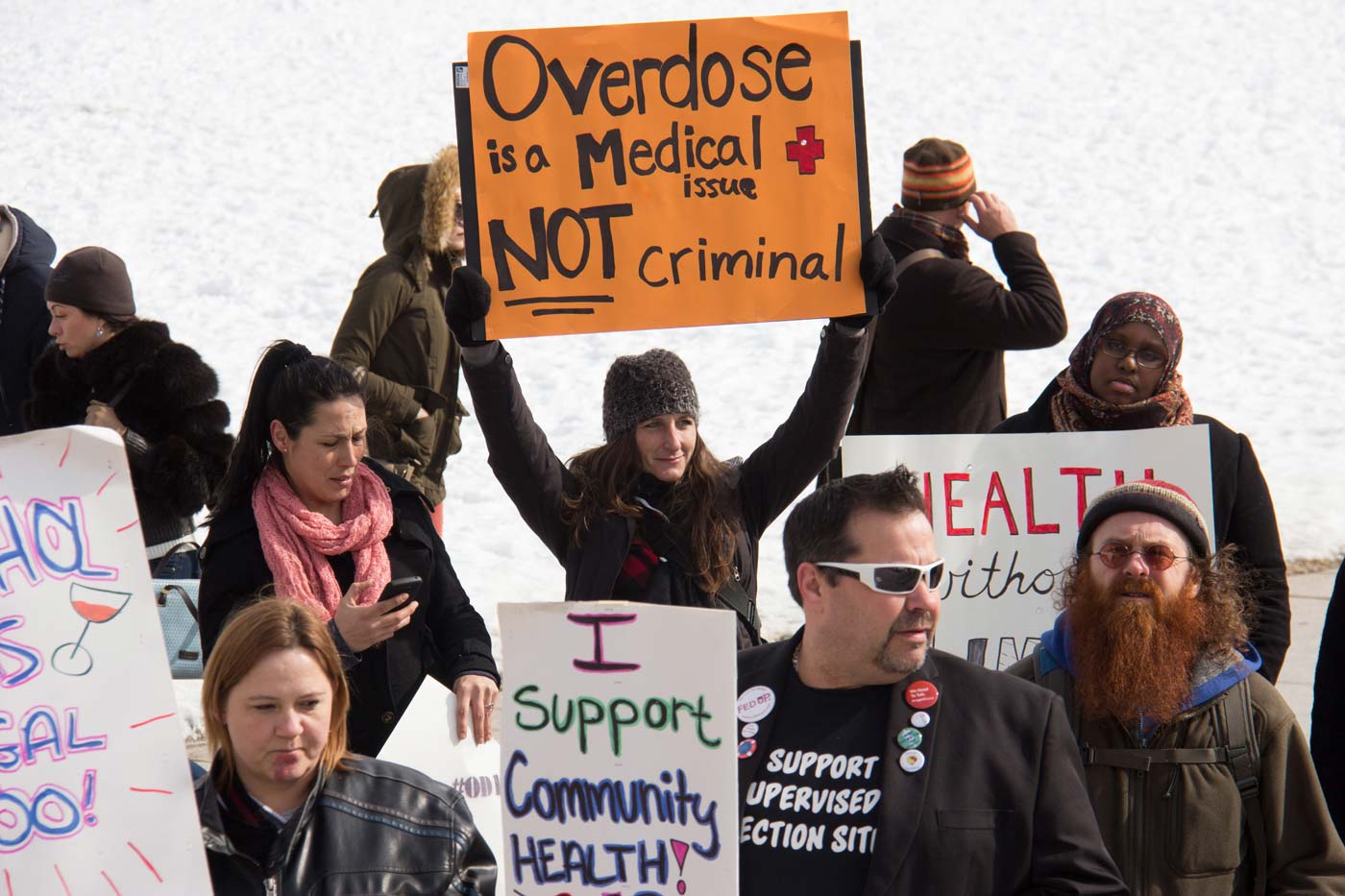

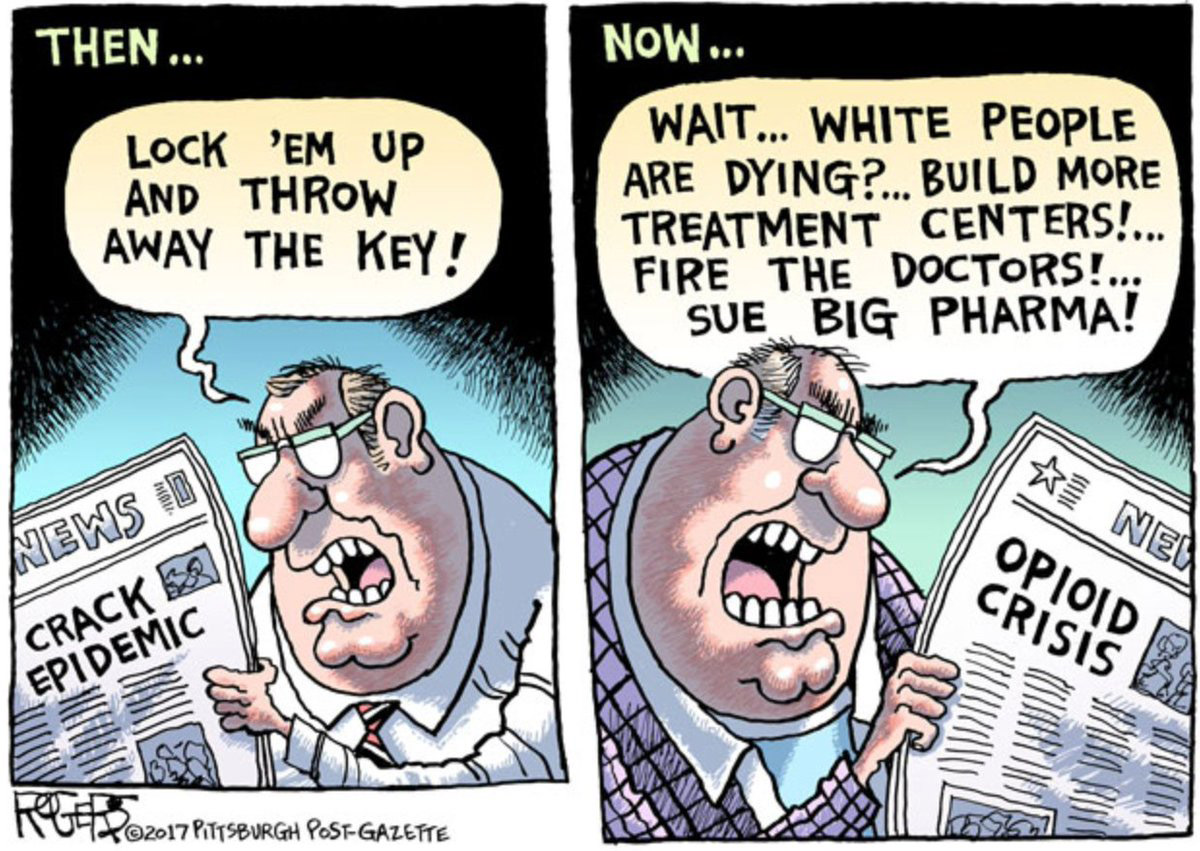

It’s obvious that this crisis is receiving very different coverage than the crack epidemic of the 1990s or the heroin epidemic that preceded it in black communities. Those waves of drug use became a pretext for mass incarceration, mandatory minimums, three-strikes laws, permissible racial profiling, and militarized schools, all of which put a disproportionately black and brown population in prison, disenfranchised of voting rights and unable to find legal work once they emerge. These ex-prisoners are therefore unable to exert even the slightest leverage on the government policies that incarcerated them via the traditional political means of voting, lobbying, and cutting deals. They are likely to be forced to break the law to survive, which may mean they return to prison.

A cynical person might speculate that it’s no coincidence drug laws are being reformed precisely when white people are experiencing this crisis. White people have always used drugs, of course, but it has only recently been considered a major problem. Although 33,000 people died from overdosing in 2015, there does not seem to be a corresponding wave of repression directed at that population. The liberal affect about the epidemic is one of intense sadness and loss, as though they are surveying the damage left by a hurricane—something beyond anyone’s control. Conservatives, as usual, have plenty of judgment to offer: users are depicted as trailer trash, judged for the very poverty that may have driven them to use. But there’s often a second note of anger: both impoverished white community members and the politicians they elect are looking for someone else to blame.

It’s no surprise who the scapegoat is. Black and brown people are always blamed for white despair. The same old tired narratives are trotted out: these drugs are coming from south of the border; they’re taking our jobs; their civil unrest is wrecking our communities. White people reminisce about when their towns used to have industry—jobs for lower-class people that supposedly promised a possible way out of poverty or at least allowed them to remain poor in a stable sort of way. Few white people, however, have turned towards radical politics in response to deindustrialization; most of the predominantly white communities that benefit from Medicaid expansion drug treatment still voted for Trump, who promised to repeal Obamacare. This is not entirely bad news, as it suggests people cannot be easily satisfied—they want something wholly different, not just harm reduction—but it is disturbing in light of how Trump’s presidency is likely to continue to affect black and brown people.

All this feels depressingly routine for anyone who has been paying attention to the dominant arc of US history. Ironically, far from being responsible for the problem, many of the migrants coming to the US are fleeing the violence of the cartels responsible for producing these drugs, which are funded by the US citizens who consume their wares, not by the Mexican and Central American migrants fleeing their zones of control.

Sure, narcotics are coming directly from Mexico into North Dakota! Mexicans must be to blame!

Many black people in the 1970s and ’80s fought against police harassment and for black self-determination and community involvement in drug user recovery—and sometimes, unfortunately, for heavier legal penalties and increased police harassment of predominantly black drug users. In contrast, many white people seem less eager to take responsibility or demand change along those lines. Self-declared sons of white America feel robbed of their birthright, and they want it back from their black, brown, immigrant, and off-shore brothers… never considering that it could be their own parents who are to blame. Some whites acknowledge that reforming their own behavior is part of the solution to their social problems, but many—such as the Proud Boys—aim to do so only in order to glorify and renew the misogynist, racist foundations of “Western civilization.”

This is ironic, in that these same racialized divisions are also responsible for preventing white workers from making common cause with others to stand up for themselves against the causes of their suffering. Deindustrialization is hitting white communities now the same way that it hit black communities in the 1980s, bringing with it the addiction and despair long familiar to more targeted groups. While fascists seek to attribute responsibility for the suffering of poor white people to people of color or some sort of Jewish conspiracy, the fundamental problem is obviously capitalism. Market imperatives make dealers and cartels seek profit at any cost, just as they reward industrial corporations that shift their production facilities offshore or replace human employees with machines. It is capitalism that has broken up our communities, compelling us to chase jobs from one place to another across the continent while extractive corporations decimate the natural world we depend on for survival. To defend ourselves against this onslaught, we have to come together across all lines of identity, identifying with each other even across gulfs of privilege and fighting to abolish privilege and capitalism entirely. One of the chief reasons race was invented in the first place was to split the interests of those on the receiving end of all the disparities and misfortunes imposed by capitalism.

But what do we do about addiction itself? In his book, In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts, Dr. Gabor Mate reviews studies performed on rats that illumine an alternative solution to the dilemmas of white America. Mate describes how researchers addicted rats to cocaine. Predictably, the rats came back for more cocaine regularly, even feverishly. But when the rats were removed from solitary, clinical surroundings and put in a natural environment in which they could find each other and engage in more interesting activity, the rats, though already addicted, were much less interested in cocaine than in the rest of their lives.

People are not rats, and cocaine is not an opiate, but the implications are clear enough. To put an end to the problem of harmful addictions in our society, we have to make our world livable. This is also a way to understand the anarchist project.

Graffiti in Montréal. The crisis is taking a toll in Canada, too.

As anarchists, we aspire to fight the causes of unhappiness and poverty, to counter the strategies that our oppressors employ to drain us of emotional and material resources that could be employed outside their marketplace. We aim to interrupt the destruction of our world and our relationships and our ability to share. If we love people who are suffering from drug addiction, regardless of their race, we must make the world a more livable place. Let’s create a world no one would want to escape, in which the idea of a drug that would make us feel less alive—or a cellphone or a video game or any other product—is self-evidently undesirable.

This means maintaining cooperative projects to support those fighting to free themselves of addiction—even Alcoholics Anonymous was founded by people reading the anarchist Peter Kropotkin to learn about how groups based in horizontal organizing and mutual aid could address their own needs together. But it also means attacking the foundations of authority in this society. When we fight against the power that capitalism and the state currently possess to determine all the possibilities of our lives, we are also fighting against the causes of addiction, racism, and despair.

Part of this undertaking is refusing to let white people blame other broke people for their difficulties. We have to show clearly who the enemy is and create avenues for finding affinity and solidarity across racial lines while demonstrating the kind of activity that it will take to solve our shared problems. We must refuse to sanction scapegoating, yet simultaneously resist the urge to treat groups of people as monsters—even those who scapegoat. The divisions that racism imposes in our communities are responsible for much of the suffering that white people experience, too—everyone has a stake in abolishing white supremacy as well as the institutions that depend on it to maintain their sway. We must introduce an anarchist tension into all these ongoing struggles for survival.

When we imagine this task on a global scale, it appears almost impossible. Fortunately, we encounter it broken up into smaller steps every single day.

For a world without despair or the power disparities that cause it.