As students head back to school for the fall, it’s a great time for young anarchists to form student organizations. But what if you’re not a student? Many young people can’t afford to go to school, yet have no better way to meet other intelligent people their age who also desire to create a better world. The following narrative traces the history of anarchist participation in student struggles in Atlanta through the eyes of a non-student participant. It shows how non-students can work with student groups to build momentum that spreads far beyond the limits of campus. To those who call this “outside agitation,” we counter: who has more right to occupy a school than those who already can’t afford to attend?

For ideas about how to organize on campus, read “UNControllables: The Story of an Anarchist Student Group.” For a little background on the history of student and youth revolt in Atlanta over the past several decades, start with the appendix below.

How It All Began

When I moved to Atlanta in 2010, I had no ambition of attending college. In fact, I’d already dropped out of high school. I didn’t set out to participate in student struggles on university campuses—but I also didn’t intend to sit them out.

Around town, various anarchist and communist groups were organizing to feed the homeless, hold meetings, provide practical skill-sharing resources, and sometimes attend small demonstrations. My friends and I were forming punk bands, reading groups, and shoplifting crews and attending art shows and parties. We wanted to live adventurously and to fight boldly alongside whoever was willing. Some of my student friends learned of a large demonstration against tuition increases at Georgia State University.

We attended and were surprised by what we saw. Out of this demonstration, a new student organization was formed. We decided to join it.

GSPHE: Participating Non-Ideologically in a Combative Student Organization

Georgia Students for Public Higher Education was a statewide autonomous student organization. There were chapters in Atlanta, Athens, Carrolton, and Savannah. This scope of organization is impressive even by today’s standards. GSPHE, at least the chapter I was a part of, was a formal organization but was not recognized officially by the university and thus did not have to obey its charters. We also did not receive money from the school.

Had my friends and I assessed whether to organize with GSPHE according to its ostensible ideological orientation, we probably wouldn’t have participated. The group was mostly comprised of liberals who wanted the schools to be cheaper and more accessible to immigrants, but were not especially concerned with the nature of the university itself and lacked a revolutionary critique of capitalism. A smaller number of influential members were socialists—some gradualists, some aspiring revolutionaries. We were a small clique of anarchists and punks; we joined in despite ourselves. It turned out to be the right decision.

In my experience, sharing beliefs with those you work with can shorten the time it takes to arrive at decisions; it can also make it easier to cooperate over long periods of time. But without the sincere desire to collaborate, no amount of shared ideology can make your group function properly.

How Did GSPHE Work?

Every chapter of the organization we had joined was free to make its own decisions and to collect and organize its own resources. We agreed on a few unifying principles and held annual convergences in Atlanta. This federation structure allowed for the maximum of creativity and collaboration under one banner. The criteria and terms of membership were explicit: attend two meetings in a row, then one meeting per month. This did not prevent GSPHE members from organizing with non-members.

Significantly, GSPHE did not ban non-students from membership.

Meetings and the Rotation of Responsibilities

Our group met in a large classroom once a week without official permission. We had a facilitator and a note-taker and always drafted an agenda together at the beginning of each meeting, although I suspected that the most dedicated members of the collective often prepared the items beforehand. This didn’t bother me, because we always had a chance to change the agenda.

Meetings sometimes lasted much longer than they should have. Sometimes we’d discuss trivial matters for far too long when we should have remained focused. As a result, sometimes consensus or majority was engineered or feigned just so we could end the meeting. When you’re working in a group that includes a lot of inexperienced people, I imagine that dynamics like this are completely normal. It takes a lot of practice to develop meeting skills, especially in facilitation and note-taking roles. This is why GSPHE always rotated tasks on a biweekly basis.

Rotating roles was important: it diminished the ways in which new or inexperienced participants were marginalized, while protecting those inclined to take on responsibilities from the tendency for resentments to build up against them. It helped to insure a greater sense of ownership in the organization and to help develop confidence and finesse among the entire group. Later, when GSPHE members were organizing with unaffiliated students and facilitating massive assemblies for Occupy Atlanta, these skills were indispensable.

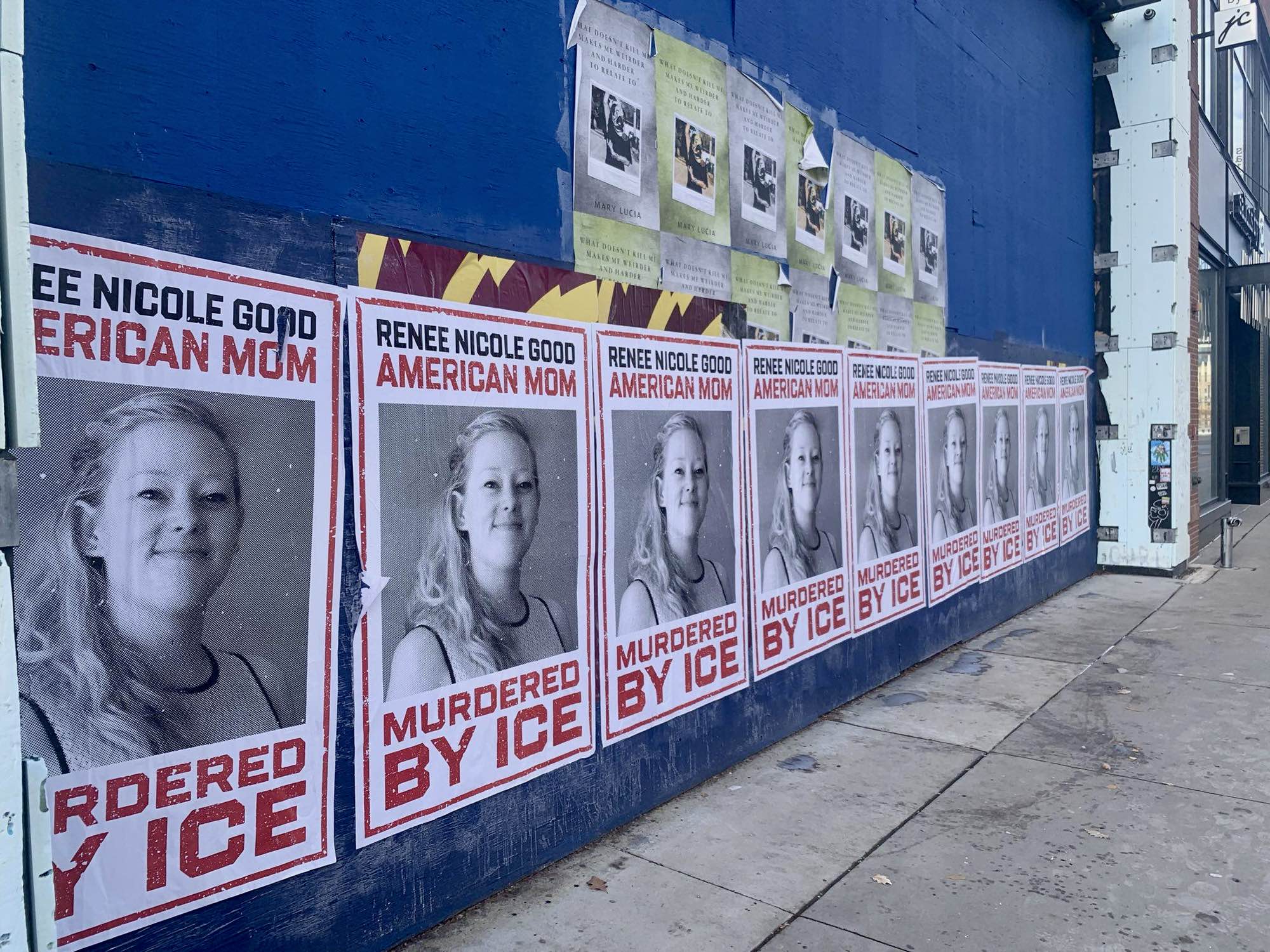

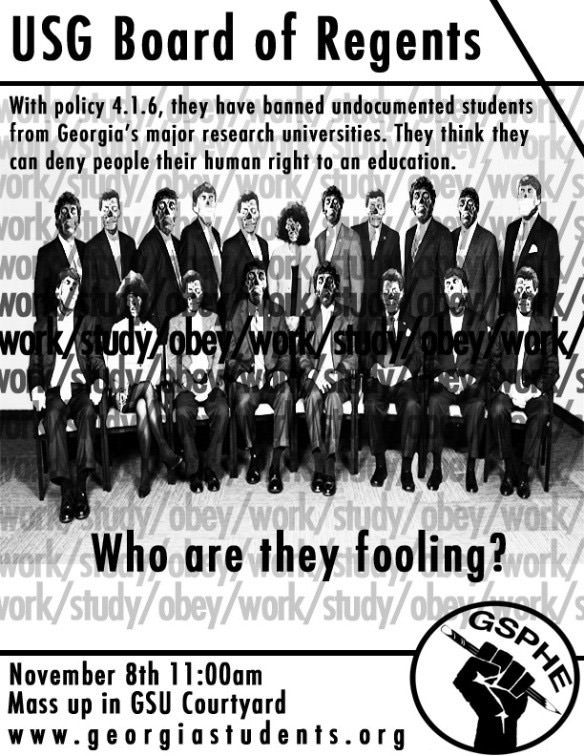

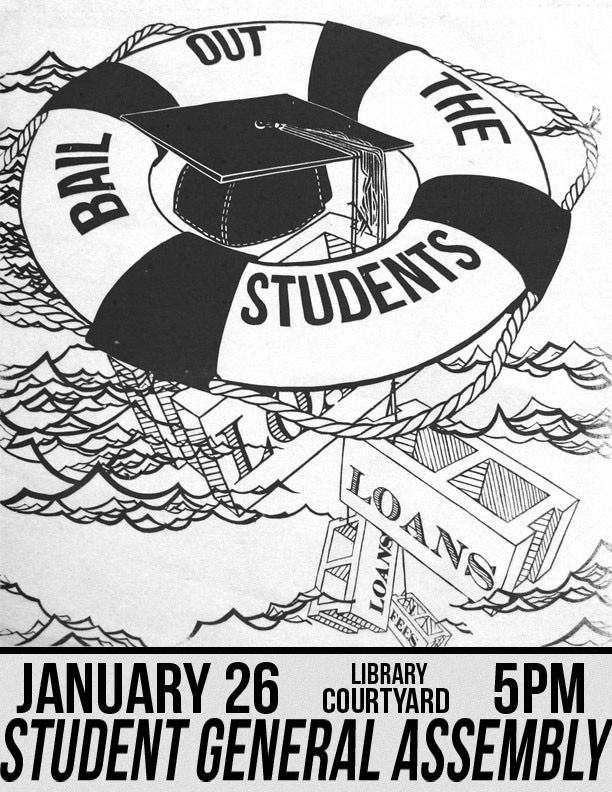

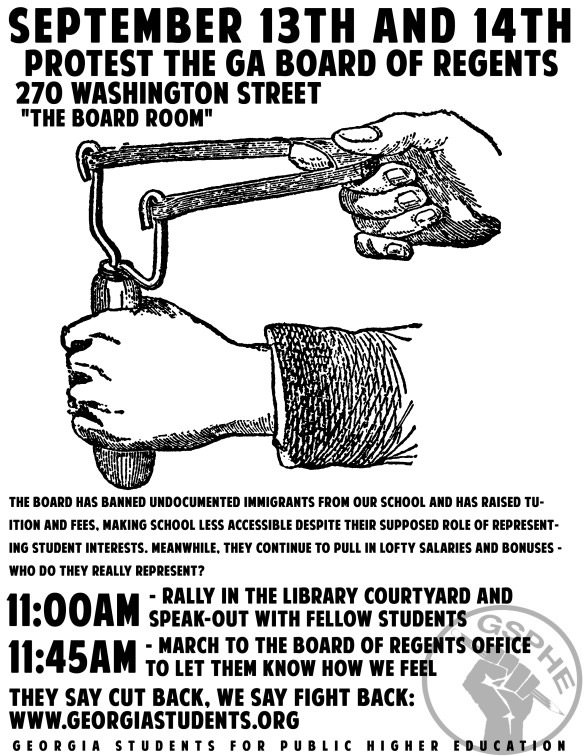

The Struggle against Budget Cuts and Bans on Undocumented Students

GSPHE grew out of an announcement by the Board of Regents that they intended to raise tuition dramatically and make cuts to the HOPE scholarship, which ensures reduced or free tuition for high-school graduates with a high grade-point average. In October, hundreds of students blocked traffic on downtown streets and joined in chants against the budget cuts. This was before Occupy Wall Street, when protests in Atlanta were rarely able to block the streets.

In the following weeks, students and non-students met on GSU campus and held conference calls with students of different universities to form the group. Non-students like myself were not discouraged from participating. This was an advantage for groups like ours. Over the following years, university administrators regularly alluded to the participation of “outsiders” in student struggles, just as police chiefs threw around allegations about “white anarchists” at Black Lives Matter protests. In both instances, there was a degree of truth to their claims, although their discourse was built on dishonesty.

In response to this mobilization, the administration scrambled to convince everyone that the Atlanta Journal-Constitution had falsely reported the fee increase. In fact, tuition and fees were increasing, and there would be cuts to the HOPE Scholarship, although not as much as had been reported. This proto-Trumpian maneuver served to pacify the general student body, but our group had already formed and we were committed to organizing together in some way. Working groups studied the intricacies of the budget cuts and presented on them to the rest of us. They also presented “teach-ins” in the lecture halls of sympathetic professors.

HB87

Later that year, in Arizona, Alabama, and Georgia, racist legislation was introduced to ban undocumented students from attending state colleges and universities. Students and community members mobilized in all of those places.

In Georgia, a new student coalition formed called Georgia Undocumented Youth Alliance (GUYA). GUYA was committed to nonviolent direct action and to symbolically petitioning the board of regents and GSU President Mark Becker to vote “no” on the ban. There was also Freedom University (FU), established as a coordination of professors and others to provide university-quality classes and curriculum to undocumented students so they could still receive an education at home and transfer the accredited courses to schools in states with less racist legislation.

GSPHE worked with both of these organizations, hosting rowdy information demonstrations in the courtyard of GSU, distributing propaganda to students, and organizing demonstrations. On one occasion, a few dozen of us sat in the President’s office for over an hour. On another occasion, students from the UGA and GSU branches collaborated to disrupt the Board of Regents vote on the ban, dropping banners and screaming at the conservative members of the Board.

GUYA organized more than one sit-in on major roads downtown. These were always organized bureaucratically (in the name of “safety,” naturally), but they always seemed to create a stir and usually caused substantial traffic delays for the government district downtown near the capitol. Unlike GSPHE, GUYA was connected to one non-profit organization and worked closely with many others. This substantially affected the culture of their organization, causing them to emphasize spectacular media stunts, respectability politics, and hierarchical organizing methods inside their organization and in the coalitions they formed with others. Because of this, GSPHE sometimes had difficulty working with them, while authoritarians groups like the notoriously self-serving Trotskyist International Socialist Organization were able to derive advantages from collaborating with them. However, neither group was more effective or bigger than ours.

In the end, unfortunately, we all failed to stop the budget cuts. Undocumented students are not technically banned from attending school in Georgia, but the bill passed bans them from receiving in-state tuition even if they were raised here. In addition, many schools have voluntarily banned undocumented students as a matter of policy.

Legitimize Yourself, There Is No Other Way

In any struggle, there are legitimate actors who can lay claim to recognized discourses of oppression to justify their rebellious desires and illegitimate actors who must conceal themselves with this discourse or present themselves as “allies.” This is a narrow line I have tried to walk, finding myself continuously with scant legitimacy in the discourses of left-wing causes. I know that I have legitimate reasons to struggle, but legitimacy is not distributed horizontally in the great game of politics. I don’t want to sign away my agency by presenting myself as an “ally,” and I don’t want to marginalize myself as an “outsider,” but the way I am positioned, it is sometimes impossible for me to act from within any of the identities on offer, such as “student.” People like me have to constantly struggle against the concept of legitimacy itself.

For the most part, the students I was working with concerned themselves with tuition and fee increases, transparency of the board of regents, the accessibility of resources to non-white students and undocumented students, and the like. These issues enabled them to understand themselves as oppressed people facing off with an aristocratic enemy. At the same time, this framework tended to sideline non-students and others with a more fundamentally structural antagonism towards the university system.

When organizing on university campuses as a non-student, I often found that I was willing to take greater risks than my student accomplices. I resisted the temptation to be judgmental about this. Students expect to be employed based on their degree—though this is less and less common—and sometimes face great pressure from their families to stay out of trouble. In our conversations, I often brought up the spiritual decay produced by schooling, the militarization of academic knowledge, and the role of the university as a capitalist enterprise—for example, the ways that universities accumulate real estate and drive gentrification. For me, the really important question was how to catalyze revolt in the downtown area, which has GSU as its center. Together, these discourses created a context in which others could recognize the legitimacy of my participation, without negating the validity of student struggles for accessibility and affordability.

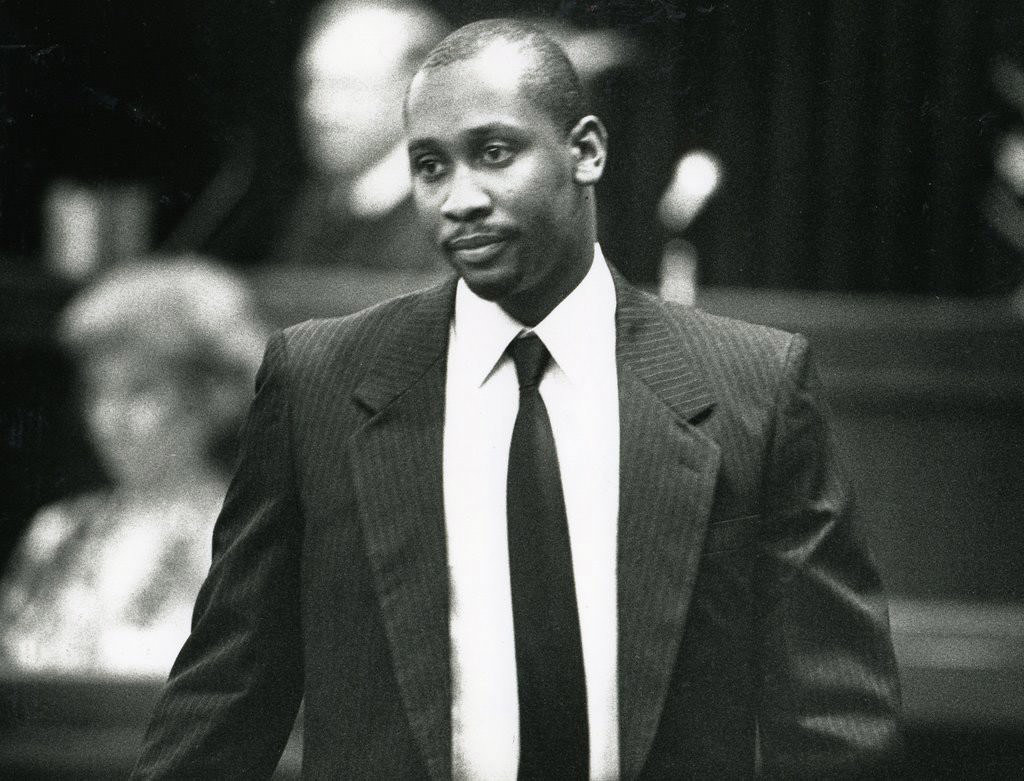

Troy Davis: Student Struggles Begin to Spill beyond the University

Many groups mobilized when Troy Anthony Davis was to be executed by the State of Georgia for his alleged killing of a Savannah Police Officer in 1989. In early September 2011, Amnesty International organized a massive demonstration outside of the Capitol to call for a “stay” to the execution. Thousands of people arrived, including most of the members of GSPHE. At the end of the rally, members of our group used our drums and megaphone to help to initiate a breakaway march of several hundred people. The crowd was angry and desperate. Some people dragged trash cans and police barricades into the street. People in the crowd cursed at police officers. Although black power groups, antifascists, and animal rights groups had once maintained a combative street culture in Atlanta (see Appendix), this sort of combative energy had not been seen in the city in years.

That night, around 100 people occupied the plaza of the Board of Pardons and Paroles, including members of GSPHE. This was September 20, 2011, when the budding encampment at Occupy Wall Street had been reduced to a few dozen hardened activists and anarchists in its first few floundering days. The next morning was the date set for the execution. Amnesty International, rather than the police, evicted our occupation after thousands had been gathered for hours. The speakers misled the crowd into believing that a stay had been temporarily placed on the execution. The tension was rising higher and higher. Helicopters began to fly overhead. Police trucks began encircling the massive crowd. Prayer and singing was coordinated over the speakers. The Amnesty organizers stalled the announcement for many hours, deliberately withholding information from the potentially explosive crowd, likely in coordination with local or federal police. In fact, Troy Davis had been executed by the State of Georgia on time.

Troy Davis, murdered by the state.

2011: The Return of Conflict in the Streets

When the Amnesty International organizers finally announced that Troy Davis had been killed, the crowd had already mostly dispersed. Many were crying. Quickly, anarchists, marxists, and student organizers met to discuss emergency plans. They agreed that militant street action was justified and organized a black bloc.

Almost nobody in that black bloc had ever participated in one before, and most participants probably would not have imagined they ever might join one before that moment. A few dozen people gathered and began marching aimlessly downtown, angry but without experiece. Eventually, the police grabbed several people and arrested them, but the crowd successfully de-arrested some of them. This event was not especially inspiring for anyone else, but it was an important moment for the participants. A threshold had been crossed.

Dozens gathered at the house of a GSPHE member to coordinate jail support. Our friends were quickly released from jail with minor fines. The conversations that followed became the basis of an intervention of great consequence in the following year. About 20 people discussed the need to go beyond attending meetings together—to see each other often, to study together, to live and work and share insights together, and to hold big meetings beyond of our little group on a semi-regular basis. We called this plan the “Atlanta General Assembly.”

And then, just in time, there was Occupy.

Student Interventions in Occupy Atlanta

At an early Occupy Atlanta general assembly, the very first week of October, there was a debate about whether to occupy a park. Meanwhile, in New York City, an Occupy Wall Street protest against the execution of Troy Davis was kettled by police who gratuitously pepper-sprayed some young women in the crowd. General assemblies like ours were cropping up in dozens of towns and cities. GSPHE members, accustomed to meetings and assemblies, played influential facilitation roles in these assemblies. A very small number of people convinced hundreds more to go through with what we all obviously wanted to do: illegally occupy Woodruff Park. The following week, we did just that.

I don’t believe we could have had this same influence if we had not developed skills organizing with GSPHE. I know it is common for angry militants to become frustrated with large crowds of liberals, to yell bitter slogans from the back or give up altogether on intervening. This is what many revolutionaries did in Atlanta and across the country. Having no experience agitating crowds or arguing in front of unsympathetic strangers, aspiring revolutionaries often fail to facilitate the emergence of combative possibilities in broader social movements. These anxieties and failures are normal; they have beset GSPHE members as well. Yet our patience and finesse helped to cultivate a more interesting organizing space during the Occupy sequence. Over the following months, this created a situation in which we were able to shut down banks, blockade streets, demonstrate against the police, occupy a home facing eviction, and carry out countless jail solidarity protests and black blocs.

GSPHE Eclipsed by Occupy GSU

With all of the attention and energy of GSPHE members focused on Occupy Atlanta, the student group completely dissolved. Former members of GSPHE and Occupy participants formed a new group called Occupy GSU.

Occupy GSU was more radical in its aims and discourse then GSPHE, although it didn’t last as long. We dropped banners on campus and threw thousands of fliers from the rooftops to cheering crowds below, we held street parties on adjacent streets and threw streamers and tinsel over the heads of police officers, we wheeled a sound system into the library during study hours to demand 24-hour access, and we organized for a walkout on campus.

From my perspective, the walkout was the peak of student mobilizations on GSU campus for many years. Dozens gathered on the top floor of the General Classroom Building. For weeks, we had been adorning the walls with posters and distributing our fliers to thousands. I don’t even remember what we were telling people we were doing it for. I’m sure the reasons were salient. We began banging drums loudly and chanting “WALK OUT, WALK OUT!” We opened the doors to the classrooms and waved students out to follow us, which many did. By the time we reached the courtyard, we were several hundred people cheering and clapping.

We should have pulled the fire alarm. We would have been thousands. Some did not want to because they only wanted people who “believed in the walk out” to attend. But that isn’t how desire works. Many people were glued to their seats, struggling with themselves about whether or not to go, uncertain of the consequences, and then the march was gone, the noise fading down the hallway, the teacher regaining control. All of those people would have had the perfect excuse if the fire alarm sounded. And what would the police have done? Never make the mistake we made. Always pull the fire alarm during a walkout.

The crowd was quickly attacked by a few police officers; they slammed one of the more vocal participants to the ground. A shoving match ensued, but we couldn’t get that person free. The crowd began booing, but that was it. Foolishly, the walkout marched to the board of regents. From that point, the stale architecture of the governmental buildings pacified the demonstrations by itself without any flesh-and-blood police being necessary. We should have had a better plan to stay where we were and to occupy the plaza itself.

Occupy Atlanta.

Autonomous Resistance Continues on GSU Campus

By the end of 2012, nearly the entire network that had comprised GSPHE had graduated from school and left the student struggle or had abandoned it to participate in subcultural anarchist and Marxist networks. For most of the participants, the disintegration of the Occupy movement gave way to a period of in-fighting and hedonistic partying. This was a common feature of the previous cycle of struggle, in which flare-ups of social unrest would grip the country for months before giving way to lulls that lasted for years. Today’s cycles are different because so many struggles are blending together and the flare-ups are happening more and more frequently. In the coming years, however, there will likely be times of widespread pacification in which it is not possible to participate in large-scale rebellion, and those will be depressing times.

Some of the GSPHE veterans wondered to themselves why they had wasted their time in a student struggle anyway, being themselves non-students or having already predicted that the group would dissolve when the majority of members graduated. But from this perspective some years later, having some distance on it, it is clear that the organization was pivotal in building skills among a large network of organizers and cultivating an autonomous and confrontational culture of resistance on GSU campus.

The Anti-Racist Assembly

In 2013, Patrick Nelson Sharp attempted to organize a “White Student Union” on GSU campus. Sharp’s connection to white nationalist and Neo-Nazi organizations spurred GSPHE veterans, anarchists, communists, anti-racists, and others to mobilize against him. Posters appeared all over downtown debunking simplistic arguments for fascist organizing disguised as “free speech.” People organized an anti-racist assembly with the intent of creating an unfavorable atmosphere for racist organizing on campus. The organizers didn’t facilitate the assemblies, but they did prevent others from dominating them. This prevented opportunists from co-opting popular rage to direct it into authoritarian organizations.

The anti-racist assembly made the news many times. Eventually, we marched into the office of the Dean of Students, some of us in masks, and threatened to create greater disorder if the “White Student Union” became a university-sanctioned group. Sharp’s campaign temporarily stalled in a storm of scandal.

Defend WRAS

The following year, in 2014, the GSU administration announced that it would be selling the student-run radio station, WRAS, to Georgia Public Broadcasting for $100,000. Students had run the station autonomously since the 1970s; this was a barefaced attack on self-organized student life. Across the city, WRAS DJs and staff organized fundraisers and events to save the radio station—but they employed no strategy beyond publicly expressing their disappointment. Another group organized under the banner of DefendWRAS.

This group was the first group to organize a demonstration, something the pacified student staffers and supporters had never intended to do. The DefendWRAS group argued that the attack on the radio station was an attack on the autonomy of students in general, not just on the radio station staff. Over 100 people attended the protest; it blocked streets and stormed into the Student Center, temporarily occupying the bottom floor where WRAS records. Students, alumni, and others chanted and banged on lockers for several hours as snitches and cops gathered at the stairs; ultimately, they opted for leaving the protesters alone. Demonstrators vandalized bathroom mirrors and wrote graffiti on the walls of the building before dispersing without arrests.

Atlanta Antifa on GSU

Starting in 2015 and increasing drastically since then, white power and neo-Nazi stickers and posters have appeared on GSU campus and around downtown. Atlanta Antifascists meticulously documented this campaign and connected several GSU students to it, including Patrick Nelson Sharp, as well as non-students like Casey Jordan Cooper. Atlanta Antifascists have also documented the participation of several GSU students in racist demonstrations at Auburn University and elsewhere in the spring of 2017.

In early 2016, undocumented students occupied buildings at University of Georgia, Georgia Tech, and Georgia State University at the same time to protest the bans on undocumented immigrants enforced by these schools. The struggle against racism and white supremacy continues in many forms.

Turner Field Resistance

In 2016, GSU and the City of Atlanta announced the sale of the old Atlanta Braves stadium, Turner Field, to Georgia State University. The same year, GSU acquired Georgia Perimeter College—making it the biggest university in the country with approximately 55,000 students. This has made GSU a tremendous force in real estate markets. A nonprofit group worked with student activists and Peoplestown residents to set up an encampment outside of Turner Field at the end of 2016 to demand a “community benefits agreement” with Peoplestown neighborhood residents. Such an agreement would transfer profits from the sale and use of Turner Field to the residents of the neighborhood rather than Georgia State or its private partners and sponsors. In December, GSU students spread this struggle by occupying the Honors College building.

They were arrested, but this offers an encouraging model of how student struggles can intersect with the needs of those off campus.

Conclusion

Many people at colleges and universities will be looking to equip themselves with the means to fight in the coming years. This is already happening everywhere else, even in high schools. Others will be indoctrinated with discourses that convince them that it is foolish or wrong to resist. But it is always the right time to organize for revolt. Whether you are studying on a campus or you simply live in a town centered around one, do not hesitate to take advantage of the school as a place to get organized. Use the campus as a space to meet with others, study the conflicts of the day, and create spaces of freedom that others can expand. If you push at just the right moment, an avalanche of possibilities will pour forth.

Be decisive. Be bold. Just as we call on the courage of those who came before us, someday someone may have to call on your example. Don’t let them down.

Appendix: Youth and Student Unrest in the 1980s, ’90s, and ’00s

The history of autonomous youth and student rebellion in Atlanta deserves a close study and analysis, for it is rich. Here, we must pass over the massive waves of revolt led by factory workers against the Klan in the 1960s, and the efforts of poor blacks to fight against discrimination and police violence during the Civil Rights and Black Power movements. For now, a quick overview must suffice.

From the late 1980s into the ’90s, racist skinheads and neo-Nazis attempted to infiltrate the hardcore and punk scenes. Anti-fascist punks fought them courageously and drove them out of shows, often with knives or bats. Many of these same punks also engaged in conflicts with the “religious right” outside of abortion clinics and Planned Parenthood offices.

In 1992, rioting exploded in downtown Atlanta for three days in response to the insurrection in Los Angeles that followed the acquittal of LAPD officers for their vicious attack on Rodney King. After a demonstration organized on Georgia State Campus, black youth burned cars and trash downtown, looted the Underground Atlanta shopping mall, attacked riot police and leftist pacifiers near Morehouse, and eluded pursuing officers all around Georgia State University. Later that year, hundreds of black militants occupied the General Classroom Building after a racial slur was written on a trashcan. In the wake of this struggle, the GSU African-American Studies Department was established. The same week, a predominantly non-black LGBT student group occupied the cafeteria to support the struggle of their black classmates and advance their own demands.

Coverage of student struggles at GSU in 1992.

By the mid-1990s, the hardcore punk scene in the US had become very influenced by deep ecology, veganism, anarchism, and other radical political ideologies. In Atlanta, vegan straightedge hardcore kids often organized rallies and marches past fur shops on Ponce de Leon and in other parts of the city; participants frequently smashed windows and vandalized the stores, often while masked. In 1996, vegan activists and hardcore punks organized a militant action against the YERKES Primate Testing facility on the campus of Emory University. Riot police gathered to protect the facility from an anarchist black bloc of several dozen—an impressive number, three years before the protests against the World Trade Organization summit in Seattle demonstrated the black bloc tactic to people around the US. Participants clashed with police, throwing stones and vandalizing their cruisers in an attempt to break into the facility. Police shot tear gas into the crowd to disperse them.

All of these clashes left traces in Atlanta—a buried legacy that we discovered as our own when we, too, began to revolt.