Like graffiti, wheatpasting is a direct action technique for communicating with your neighbors and redecorating your environment. Because it’s easy to mass-produce posters, wheatpasting enables you to deploy a nuanced, complex message at a large number of locations with minimal effort and risk. Repetition makes your message familiar to everyone and increases the chances that others will think it over. If you’re looking for posters to paste up, we offer a wide selection of poster designs to print out or order in bulk.

This is excerpted from our book, Recipes for Disaster, which details a wealth of related tactics.

Making Paste

To make wheatpaste, mix two parts white or whole-grain wheat flour with three parts water, stir out any lumps, and heat the mixture to a boil, stirring continuously so as not to burn it. When it thickens, add more water; continue cooking it on low heat for at least half an hour, stirring continuously. Some people add a little sugar or cornstarch for extra stickiness; don’t be afraid to experiment. Wheatpaste, once made, will last for a while if kept in sealed containers, though eventually it will dry up or become rotten—and sealed containers of it have been known to burst, to unfortunate effect. Keep them in a refrigerator if you can.

You can also obtain wallpaper adhesive at any home improvement store; this comes in pre-mixed buckets or boxes of powder. Wallpaper adhesive is much quicker and easier to mix than wheatpaste, and not much more expensive even if you are paying for it. Don’t get the brands advertised as “easy to remove,” obviously—get the most heavy-duty adhesive available.

Posters

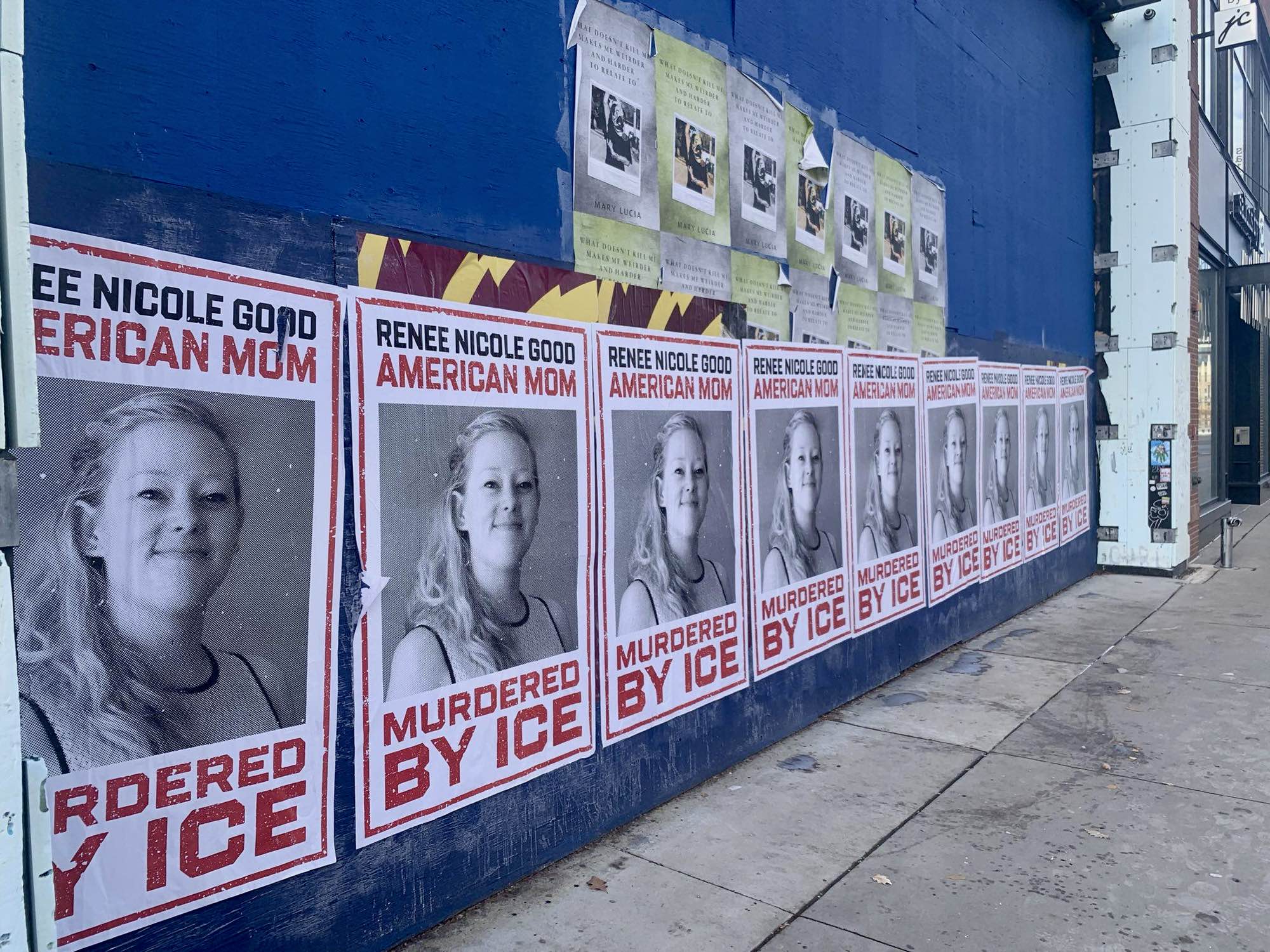

If you’re wheatpasting to express information or ideas, good design is key to getting your message across. Remember, most people will see these from a distance, so make the headline huge and legible and use images that are simple, high-contrast, and equally large. Be sure the headline communicates the basic idea on its own. You can also include a paragraph or so in smaller print for the casually interested, and it’s always a good idea to add a webpage address or similar link for those who want to pursue things further.

Don’t limit yourself to pasting up standard-size photocopies; many photocopying franchises offer much bigger options. You can make huge posters to put up; if such printing technology is unavailable, you can paste up big images comprised of smaller copies. Be creative: you could also paste up old anarchist newsprint publications, or those police target-practice sheets with photos of masked men on them, or bus schedules screenprinted with artistic designs, or income tax forms stenciled with the appropriate messages about taxation, representation, and exploitation.

This may seem counterintuitive, but the thinner the paper, the better—thin paper takes paste better, and will be more likely to rip off in tiny pieces rather than all at once if an art hater takes a dislike to it. Another way to foil such philistines is to run a razor quickly down and across each poster several times immediately after you’ve pasted it up; a pasted poster sliced in this manner will only come down one small piece at a time.

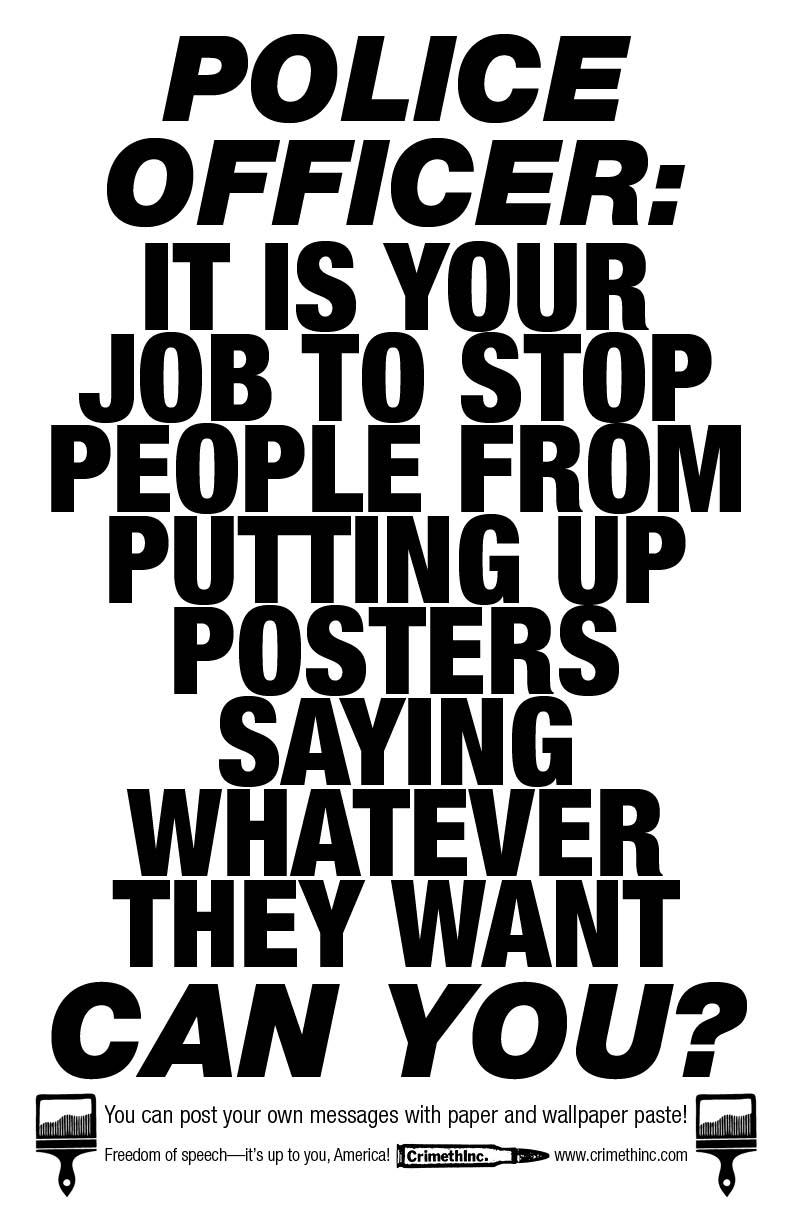

A new poster for you to put up!

Click above for a downloadable PDF.

Technique

If you’re pasting up a lot of small posters, carry them in a way that enables you to access them easily without it being obvious that you have them. A messenger bag will serve for this—just make sure you can reach into it and slide one out without much fumbling. If you’re posting great big posters, roll them up, top side out so you can swiftly unroll them down the wall, and rubber band them individually.

You’ll need a container from which to apply the paste. Wheatpaste tends to be thick, so a vessel with a wide mouth such as a large plastic bottled water container is well-suited for it; wallpaper adhesive tends to be thinner and more consistent, so it can be dispensed out of smaller holes, such as that of a dishwashing soap container with a pop-up nozzle. It can help to have something to smooth the posters up on the wall—a window-washing squeegee from a gas station will suffice, or you could get a plastic wallpaper smoother from the same retailers that provide wallpaper adhesive. Big paintbrushes can speed the application of wheatpaste, too. You could do all of this with your hands, but it will leave you messy.

For each poster, pick a good location, and make sure it’s clean; most smooth metal, glass, or stucco will take pasting nicely, while wood or concrete will be somewhat less accommodating, and brick even less so. Next, apply the paste. The more wheatpaste you use, the longer it will take to dry, so use the minimum amount to make all of the poster stick. If you’re using smaller posters, spread paste over the wall, place the poster on the pasted area, smooth out all air bubbles and wrinkles, and spread some paste over the top to hold down the corners. If you’re using larger posters, unroll them flat on the ground and apply the paste to their backs there, then put them on the wall, smooth them out, and add another layer of paste. Starting out on the ground renders you less conspicuous while you’re making sure the paste is evenly applied.

When you think about where to paste, balance the length of time the poster will probably stay up against the amount of traffic the location gets, factoring in the question of which demographics will most appreciate your design. Often, it is better to put up a poster in an alley that will remain for six months than it is to put up twenty along Main Street that will be gone by noon.

Because wheatpasting is somewhat less than legal in many places, it doesn’t hurt to go about it inconspicuously. Late in the evening can be a good time for it, when the streets are quiet but not yet empty and you can pass yourselves off as students going to a party or workers walking back from a bar. Behave as though what you’re doing is perfectly legal, while being careful not to do it before the gaze of the authorities; you’ll be surprised what you can get away with. Even in cities locked under the control of thousands of riot police, anarchists have still been able to decorate whole districts with posters.

A bicycle can be a useful accessory for postering. You can carry supplies in a basket on the handlebards, and it can function as a ladder to reach places where your art is more visible and harder to remove. It can also assist you in making a quick getaway, should the need arise. Also, bring something to clean up with—even if you wear latex gloves to keep your hands from getting sticky with wheatpaste, it can get all over your clothes, which is a dead giveaway that you’re the culprit.

Applications

A well-coordinated group can cover a city in posters in the course of a single evening: divide up the area, set the target locations in advance, and carry out the action quickly so you’ve all disappeared by the time people notice the new posters everywhere. Wheatpasting can also be applied to rework the images and messages of billboards. A group attending a mass mobilization could make wheatpasting kits including ready-to-use wheatpaste, posters, and maps showing vulnerable zones of the city to distribute to other groups with time and energy to apply.

Finally, you could put up posters with this wheatpaste recipe on them and a call for submissions, encouraging others to participate in decorating your town.

Appendix: Adventures in Wheatpasting—A Narrative

Most wheatpasting goes so smoothly that there’s not much to tell, but it’s always possible to push the limits, and this is the story of a time we did just that.

It was the night before the one-year anniversary of September 11, 2001, and we had scammed over two dozen posters five feet tall and three feet wide from the local photocopying franchise with which to address the pressing issues of terrorism and war. We had cased our city and identified the prime locations for these, in the downtown shopping district and along a few major thoroughfares. We mapped out the area and established the best order for visiting these locations, so we could get the most done in each section of the city before police could take note of our activity, and then move to another zone.

We divided five roles between us. One of us would ride a bicycle, doing reconnaissance in a radius of a few blocks around every site. The other four of us would travel in a vehicle. This vehicle would drop off a scout to stand lookout at one end of a street, as most of our targets were on one-way streets, then drop off the two people who were to do the pasting around a corner out of sight from the target, before driving down the cross street to keep watch from another direction. After the two had decorated the sites chosen in that area, they would meet the driver around another quiet corner, and the three would pick up the pedestrian lookout and move on to the next area, followed by the bicyclist. The driver, the bicyclist, the scout, and the pasting team were all connected by two-way radios with earpieces so news of the movements of police or others could be immediately relayed among us. The corporate news media had made a big deal about the extensive security precautions that had been made for this anniversary; accordingly, we were taking precautions of our own.

We spent a couple of hours brewing wheatpaste, then went out around midnight. We hit all our targets downtown without any trouble to speak of; at one point, the bicyclist informed us that a police officer had stopped a motorist a couple blocks away, but we did our work quickly and were out of there before the police car moved.

Having done some smaller-scale wheatpasting in which we were trying to pass as law-abiding citizens, it was actually a bit of a relief to be running around in all black with huge plastic jugs of wheatpaste and rolled posters. Everything was on the table and it was just a matter of moving fast and staying aware. We dashed past a civilian at one point, and I said hello—he just stared at us like we were Martian invaders.

The last target was a freeway underpass, where eight columns held up the other highway. We were to put up eight posters, four facing each traffic direction. After so much success, we were starting to encounter some problems: our clothes had inevitably been covered in wheatpaste, and it was starting to clog the microphone and earpiece of our two-way radio. All the same, the scouts took their positions and we were dropped off next to the underpass to finish the job. Ducking down whenever cars came and jumping up to apply the posters between them, we did four columns, then leaped over the concrete guardwall to run across the freeway. In a scene out of slapstick comedy, I was holding the wheatpaste in one hand and the posters in the other, and so had to hurl myself over the wall, crashing absurdly on the asphalt without my hands to break my fall. My friend helped me over the other wall, and we began the fifth column.

At this point our radio made some kind of noise, but it was impossible to make out the words through the wheatpaste. An instant later, headlights appeared, and we got down behind the column, moving slowly around it as the car approached and passed us. It was a police car. It kept going, so we set back to work wheatpasting, but no sooner had we done so than headlights appeared from the opposite direction, and we had to work our way around the pillar again, hiding as another police car drove by. This was starting to look bad. It was impossible now to get our radio to work, so, abandoning the posters, we set out walking quickly away from the underpass. As more headlights appeared ahead, I tossed the last jug of wheatpaste into the bushes.

We turned down the first side street we reached. Wheatpaste stains more visibly on dark colors; in our black camouflage with paste stains all over it, we looked more than a little suspicious, especially so late at night in a district with no pedestrian traffic. Worse yet, it turned out the street we had turned down was a long corridor with no exits on the sides, running through a closed warehouse district—no alibi could adequately explain our presence here. At that moment, a police car turned onto the street, slowing to a crawl as it approached us. We kept walking, maintaining our conversation as calmly as we could, acting as though we were oblivious to the policeman as he inched past, blatantly staring at us.

Strangely, he kept going! Seeing that we had no posters or paste, he must not have felt that he had enough evidence to justify arresting us—though the stains on our clothes would have given us away on closer inspection. We made our way down other side streets and walked all the way back to our secret hideout, where the others were waiting, relieved that we had escaped and excited to tell us about the police cars that had started following them and forced them to abandon us.

We slept a scant few hours, then went out shortly after morning rush hour to inspect our work.