In 2005, when the rulers of the eight most powerful countries in the world gathered in Scotland, capitalism seemed invincible and eternal. Most protesters limited themselves to begging the G8 to be nicer to the nations on the receiving end of colonialism and imperialist wars. Yet a few thousand anarchists, recognizing how short-lived “the end of history” would be, set out on a seemingly suicidal mission to blockade the summit and demonstrate what sort of resistance it would take to create another world. Today, as the 2017 G20 Summit in Hamburg approaches, we publish this retrospective to keep the adventures and lessons of 2005 alive as part of the contemporary heritage of the international anarchist movement.

The 2005 protests took place years after the heyday of anti-summit protesting—after the triumphant victory over the WTO in Seattle in 1999 and the courageous struggles against the IMF in Prague in 2000 and the FTAA in Quebec and the G8 in Genoa in 2001. Yet the mobilization in Scotland showed that it was still possible to challenge the rulers of the world on their home turf. Anarchists confronted the forces of the world’s eight most powerful nations right outside their gala gathering—shutting down highways, tearing down fences, and almost preventing their meeting altogether. The attacks that fundamentalist bombers carried out in London the same week looked cowardly in comparison.

Unfortunately, in the popular imagination, the suicide bombings that killed 52 people in London during the summit overshadowed the more ambitious and life-affirming counter-summit demonstrations. Whether they serve an existing government or seek to create one, the violence of those who pursue fundamentalist and nationalist projects is intended to close the field to any real alternatives, promoting a “clash of civilizations” in place of a struggle against oppression. The powers that be are much better situated when they can point to rival powers that pose an equal or greater threat to their citizens. Together, the state repression, grassroots resistance, and fundamentalist terrorism of that week in 2005 foreshadowed the ugly situation we find ourselves in today.

Police preparing to attack the “Carnival for Full Enjoyment” in Edinburgh on July 4, ahead of the summit in Gleneagles.

The Background

Britain was the nation in which industrial capitalism first took root, and accordingly it has often been ahead of its time in the art of protest. The British anti-roads movement of the early 1990s was a harbinger of the “anti-globalisation” movement in Europe and the US, featuring a wild and eclectic focus on direct action and cultural resistance in contrast to the notoriously boring politics of the institutional Left. The model was moved with much success into the cities in the form of Reclaim the Streets, capitalizing on the fact that in Britain hordes of ravers would show up just about anywhere for a good party. Within a few years, people in cities from Brisbane to Bratislava were reclaiming the streets. Coinciding with the G8 Summit in Cologne, the Global Day of Action against Capitalism on June 18, 1999 paralysed the financial centre of London, prefiguring the shutting down of the WTO in Seattle a few months later.

But every boom has a backlash, and as Britain’s turn came to host the G8 in 2005, things looked grim. The last successful anti-capitalist mobilizations had taken place years before, and though anarchists had participated in protests against the war in Iraq, many were convinced that mass mobilisations were no longer an effective means of resistance. Early meetings to discuss the G8 summit consisted of arguments about whether a truly anti-authoritarian mobilization was even theoretically possible.

Despite this malaise, the anti-capitalist network Dissent! came together nearly two years before the summit to mobilize resistance. Composed of collectives from throughout the UK, Dissent! was intended to be inclusive and accessible, though the lack of solid press relations sometimes enabled the mainstream media to portray them as secretive and sinister.1 Hashing out a plan also proved difficult: a centrally organized attack on the summit à la Quebec or Genoa seemed suicidal, and many in Dissent! feared the possible repercussions of organizing illegal activity, but decentralized protest models without central coordination had proved utterly ineffectual. The large reformist coalitions were organizing their protests a great distance from the summit, several days before it even began, so they could not be counted on to offer any opportunities. Eventually, a strategy developed based on the model that had been applied at the G8 protests in Evian in 2003: autonomous groups would blockade the routes leading to Gleneagles—the rural hotel at which the summit was to take place—shutting out the delegates, staff, and media. To this end, a campsite—the “Eco-village,” designed to be a working model of a sustainable community—was secured within hiking distance of these roads.

Organizers solicited international participation via meetings in Germany, Spain, and Greece, and little stickers appeared everywhere announcing the upcoming protests. Under this pressure, the Socialist Workers’ Party, attempting to prevent the defection of more militant protesters to Dissent!, announced that their front group G8 Alternatives would host a peaceful march to the fence surrounding the summit regardless of whether or not they were granted a permit. Two days before the G8 summit began, the streets of nearby Edinburgh were transformed by an anarchist carnival that ended, characteristically, in clashes between angry locals and police. The stage was set for something to happen.

“Must we stress once again that the G8 is here to safeguard your freedom?” Police attacking the Carnival for Full Enjoyment in Edinburgh.

The Suicide March: An Anonymous Firsthand Account

Originally published immediately afterwards as “This Is How We Do It: An Anarchist Account of the G8 Actions”

From the beginning there was no well-thought-out master plan for shutting down the G8 Summit at Gleneagles. In fact, some of us even dubbed the march we were about to embark on “The Suicide March.” At three in the morning, a large group of militants dressed in black slipped into the darkness of the night as the first rain of many days dumped down on them. The air was thick with the eerie presence of a thousand determined individuals beginning to walk along the deathly still road. Besides the occasional attempt at a chant, the group was quiet, perhaps reconsidering the slim probability of success. Five miles and a heavy police presence stretched before us and our only destination in sight: Motorway 9 (M9). This motorway was one of the crucial motorways that delegates and support staff to the G8 Summit expected to travel down in a few hours.

Wednesday, July 6th was determined to be the day of blockading the G8 by calls to action from People’s Global Action (PGA), the same loose network that had called for the day of action against the WTO six years previous. The idea of blockading was ratified at the five-hundred-person international anarchist assembly in the ancient halls of our convergence space at Edinburgh University on Sunday. The next day, a street party called the “Carnival for Full Enjoyment” (as opposed to full employment) took to the streets of wealthy downtown Edinburgh in order to protest wage slavery and the G8. Any doubts about the no-compromise nature of the militants who had converged here in southern Scotland dissipated rapidly in downtown Edinburgh on Monday when police attempted to stop the Carnival of Full Enjoyment only to be met by quick-moving breakaway marches and a front line that refused to be intimidated. And this was only the beginning, a taste of what was to come.

We left Edinburgh for Stirling, Scotland. Our destination was the “Hori-zone”, the Eco-village set-up as the point of strategic coordination, encampment, and support for the vast network of anarchists and other activists who had come to Scotland in order to halt the Group of Eight (G8) summit meeting on its opening day in Gleneagles. The camp was organized by Dissent!—an international anti-authoritarian network of resistance against the G8. The small town of Stirling is practically equidistant from Glasgow, Edinburgh and Gleneagles, and historically has been the major crossroads upon which all battles for control of Scotland had been fought. Gleneagles, a ridiculously luxurious golf course and hotel, became the heavily fortified home to the G8 meetings—but it has very limited facilities. Most of the delegates and support staff for the G8 were staying in Glasgow and Edinburgh, the two major cities in Scotland.

The Eco-village.

Since Stirling is nestled between these three cities, the Eco-village provided the perfect location for launching the rolling blockades against the G8 on Wednesday, especially along the crucial M9, the motorway that eventually reaches the front door of the Gleneagles hotel itself. The Wallace monument stood silently against the gentle skyline on a hill above the Eco-village as we prepared to blockade a total of thirty miles of highway. Built in 1869, this two-hundred-and-twenty-foot monument is said to be where the legendary Scottish rebel William Wallace observed the English coming across Stirling Bridge in 1297 before descending into a fierce battle with them. One cannot help but notice the parallel between the ancient anti-colonial battles of Scotland and the battle against the G8 that was waged in the rolling green hills of Scotland last week.

At the Eco-village, we were assembled at the very last minute to determine how we were actually going to blockade the G8. As the deadline for the action came closer and closer, it was decided that the initiative to carry out the blockades should be left to autonomous affinity groups and each departed to find their own route to the motorway and blockade it by whatever tactics they chose. A major factor in this decision was the unfortunate location of the Eco-village. The campsite was surrounded by Forth River with only one exit leading out, which could be easily sealed off by police. To avoid such an entrapment, affinity groups began leaving the site around twelve hours ahead of time to situate themselves in the forests or small suburbs along the motorways that fed Gleneagles from all sides, allowing them to spring into action as the delegates arrived in the morning.

While groups were streaming out of the site, about two hundred people were meeting to determine whether or not to have a large mass march leaving the camp, and if so, how it would be organized. This is how the suicide march came about.

“Suicide” was not a word chosen hastily. How could it be possible for such a group to actually make it to the distant M9, the major highway connecting Glasgow and Edinburgh to Gleneagles, before being stopped and contained by a ten thousand strong police force assigned to the protests? Even if the march had failed, it would provide a crucial cover for the clandestine groups to launch their siege on the various junctions of the motorways. The group decided against all odds that the risk was worth it, and the march would begin shortly. At two am, it finally felt like it was on.

The march leaving from the Eco-village in the early morning was an international contingent with some of its members coming from the UK, Spain, Germany, Ireland, France, Denmark, Italy, Switzerland, Turkey, and the United States. Morale was high as the rain poured down steadily, but little did we know that this thousand-strong militant group would have to battle through five police lines to reach its destination. The determination of the anarchists was heavy, and as we swelled in numbers a group of about eight with thick pieces of wood around seven feet long moved to the front with the purpose of clearing the way for the march to proceed. One group, clad in shields made from trashcan lids and foam padding taped onto their clothes, bore an ironic banner declaring “Peace and Love.”

Footage following the Suicide March through the early morning of July 6.

The police force mobilized from around the UK to protect the G8 summit was completely incompetent. Poorly assembled police lines were sometimes composed of front line officers who, instead of arriving in riot gear, came wearing fluorescent yellow jackets to face protesters. The police were armed often only with batons and tried their best not to use them. Perhaps this was a de-escalating tactic, considering the police seemed to be primarily set on avoiding violent engagement with protesters and instead sought to simply contain them and apply their infuriating “Section 60” order that allowed them to stop and search any suspects for weapons. Had this been any other G8 country, many of the plans implemented on the Day of the Blockades, especially the Suicide March, would not have accomplished their goals.

The quickly moving group had proceeded without interruption for fifteen minutes when the Scottish police finally got their act together and moved a line of cops into the group’s path. This happened at a roundabout surrounded on all sides by car dealerships, though at this point the group was not distracted by damaging corporate property. We had set our eyes on the prize: to disrupt the roads leading up to G8 Summit. The determination was there, but there was no backup plan. After a quick assessment of the situation, it was decided that the line of police was too deep to take on, and the group began moving back in the direction it came from to find another way on to M9.

Retreating in order to find another path to the M9 meant building barricades on the way. We found a big pile of palates in a nearby construction site and piled them into the street. During the somewhat chaotic process of finding another road leading to the highway, the crowd stumbled upon a suburban mall area that included a branch of the Bank of Scotland and franchises of Burger King, Pizza Hut, and Enterprise Car Rental. Some members wanted to keep on moving and not be distracted by the corporate property, but the rage against the corporations could barely be contained, and windows were smashed and walls were spray-painted with slogans.

When the bloc left the corporate oasis, we found a sign to a road leading to the M9 and the march surged. A couple of trolleys [shopping carts] were taken from the shopping district and were filled with fist-sized rocks from the sides of the road, the perfect ammunition for the class war. A German comrade with a bicycle was among the group and able to ride ahead as our scout and alert the rest of us of intersections and police movement. He came back and told us of a police line forming in our path. A few people moved into the field on the left to outwit the police. The rest decided that this was the moment it was necessary to throw down.

The police line was weak and did not have any riot gear apart from their shields. Those with big sticks moved to the front lines and the militants behind picked up stones from the shopping cart. We marched right up to the lines and began smashing through with stones and sticks. The police were not prepared for such determination, and after thirty seconds they scurried away. When their retreat was obvious, I heard a thick German accent scream “DEESS ISS HOW VE DO IT!”

The road was wide open as we marched the long distances from one roundabout to the next, following the road signs to M9. We came across four people wrapped in trashbags, who peeked their heads out from the side of the road in amazement at the march passing by. They were part of the hundreds who had left early to hide among the trees, completely drenched by the continual rainfall.

Our crew included a significant number of locals who were eager to represent their own culture of resistance. One middle-aged Scottish member of the group from Glasgow carried a bodhran, the traditional Celtic drum historically used in battles and parades. Another Scottish youth had a didgeridoo that was blown at crucial moments of battle to build up the energy. In the face of such a crowd, it looked as though the police had given up.

We made it the onramp to M9. This was it: victory. After trekking five miles in the rain and through police lines, there was only 70 feet between us and the highway. But these things are never so easy. Scores of police vans appeared from around the corner and unloaded hundreds of riot police. It seemed to be too much to take on, and we moved back. This time, the police seemed as determined as we were and brought another line of riot police to our only exit.

There was one option left: to battle our way out. The restocked trolleys rolled to the front and stones began raining down onto the police, thumping against their shields to the steady battle beat of the bodhran. In one of the most creative use of local resources to create weaponry, even the shrubbery was turned upon the police. This area of Scotland is known for a poisonous plant called Hogwart that has a flower that causes huge welts and blisters when touched. At one point, the bloke from Glasgow grabbed one of these plants from the stalk and beat the police with its flower. After five minutes, the police lines were pushed back fifty feet and a small path leading into a suburban residential area was revealed to one side. As we walked down the path into suburbia, there were only 250 people remaining. Most of the initial crowd had separated at various police lines to disappear into fields or return to camp. Though we were few, we had demonstrated our determination.

Participants in the Suicide March clash with police, damage an unmarked police car, and barricade the streets on the morning of the 2005 G8 summit.

A woman in a white bathrobe walked out of her house baffled at the march going by her community at 4 am. The police would later report that damage was done to people’s homes, cars, and satellite dishes. However, the only property damaged was corporate and police property and the police eventually had to retract their statement. In fact, the woman in the white bathrobe was friendly and she waved at us. We even asked her for directions towards the M9 and she showed us the way.

We had been thrown off our original route and now had to find a new way to the motorway. The police had mobilized a much larger force and were coming toward us from multiple intersections. As we rambled through the unfamiliar suburban streets, police would appear from one side, retreat under the force of the bloc, and appear again from a new direction. The sun, which only sets for about four hours between midnight and 4 am in Scotland during summertime, was now peeking over the horizon. We were wet, cornered, and lost. Another resident of the area stopped while passing in his pickup and pointed us toward the highway. His directions weren’t the most conventional: “Go down that road and climb down the valley, across the fields, through the trees and that is where the motorway is.” We had come this far, there was no way we were going to turn back, even if it meant hiking through the fields.

Standing on the edge of the hill, next to a golf course, one could see the trucks travelling on the highway far away. We quickly referred to a topographical map, concerned that there might have been a big drop to the side of the highway that couldn’t be climbed. It looked doable. Those remaining of the international anti-capitalist black bloc, tired from hours of breaching police lines and soaked to the bone, began a Viet-Cong-style journey towards the motorway we had to blockade to prevent the G8 from meeting.

In a moment of bizarre humor, one of the Scottish blokes among us was understandably concerned about marching on the golf course and warned the rest of us: “Don’t Walk on the Green!” I turned back to observe how many of us were left at this moment and was confronted with the surreal scene of hundreds of comrades dressed in black hiking single file through the luscious green landscape of Scotland. Seeing us there, hours and miles later and still on the move, I realized that most likely the Scottish rebels fighting the English had also passed through these fields centuries ago.

We continued on like this, passing through scenes of another history, through a golf course, three different cattle pastures, and knee-high grass as we walked towards a quickly approaching future of our own. Under a pale blue sky, we finally reached the motorway. We were the first group to make it onto the highway, but definitely not the last. At that moment, the rain stopped.

Delirious from walking and drunken with success, we all began to assemble anything and everything we could find on the side of the road—tree trunks, rocks, branches. It was 6 am and both directions on M9 were blockaded.

Blockading the roads; Seattle’s Infernal Noise Brigade on the march.

Walking back to the campsite later, we passed the residents of Stirling trying to go to work on the backed up roads. The reactions we got were varied but clearly split into two different groups. People who were in personal vehicles were upset at the delay and called us many things, most notably “Bastards!” Those who were in busses and vans and could be identified as construction or roadside workers by their bright yellow vests were fully supportive. We were greeted by raised fists, cheering, and others shouting “Power to the People!” out their windows.

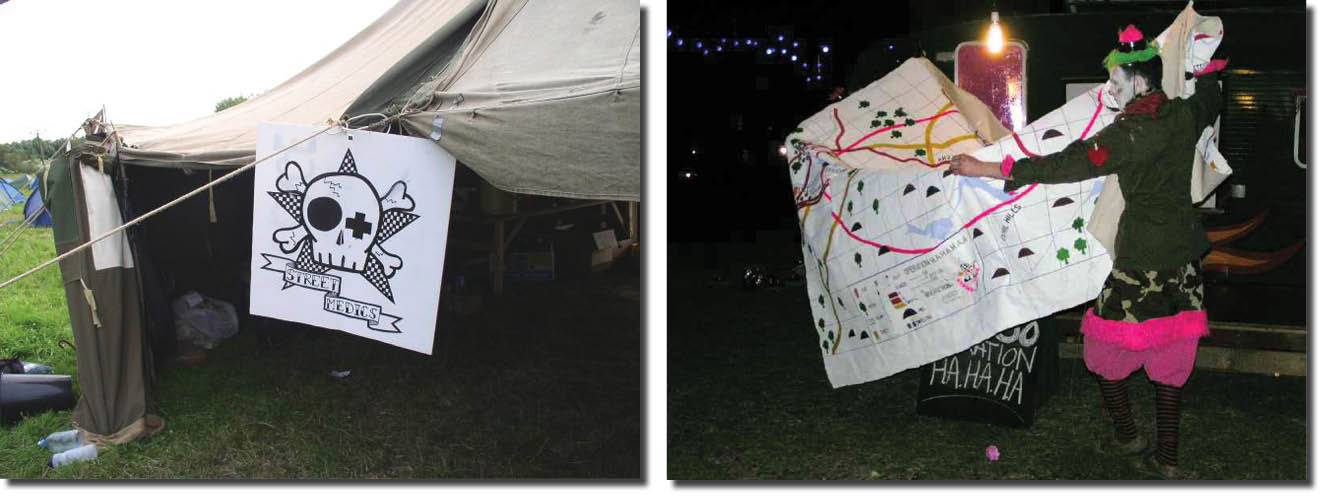

We returned to the Eco-village. At the entrance to the camp, there were two permanent flags strung high to identify the political nature of the inhabitants—the red and black flag of social anarchism and the rebel skull and crossbones of piracy. Inside was a vast space of camps, organized by either the geographic origin of the inhabitants (e.g., the Irish “barrio”) or by clusters of affinity groups working together (e.g, the Clandestine Insurrectionary Rebel Clown Army—CIRCA). A central corridor was lined with different activist support tents, eight different kitchens, medical services, an independent media center, trauma support, action trainings, and huge tents for the periodic spokescouncil meetings taking place. Beyond this central corridor was a multi-colored sea of hundreds of personal tents. Many of the tents had one version or another of black and red flags with the anarchist circle A flying above. We had arrived home.

The Eco-village was buzzing with activity. The intricate communications network that had been set up was functioning in full force. Bicycle scouts who were situated at major cities where delegates were staying, along the side of the highways and at major junctions, were providing up-to-date information on motorcade movements and alerting the affinity groups hiding along the highway when and where to strike. An informational tent at the entrance had a detailed tactical map with a large scale, providing breaking news on the different blockades of the summit. As the day progressed, one note after another appeared on the map marking the points of the blockades:

7:00 AM - Spanish Block on M9, 7 arrested

8:00 AM - 4 Protesters with ropes dangling off a bridge on M9

12 PM - Group of 50 including CIRCA and the Kid Bloc having picnic on the Motorway with massive amounts of riot cops looking confused

All railroads leading north have been halted by activists locking themselves to the tracks.

This was only the beginning. The notes continued appearing throughout the day: a bicycle contingent took over A9 at 4:00 PM, the Belgian and Dutch Bloc locked down on Kincardine bridge at 4:20 PM, and so on.

The Eco-village was the epicenter of brilliant tactical coordination. This was a result of months of reconnaissance work and a chaotic yet functional plan of blockading that provided both fluidity and agility. As soon as a report would come in that one blockade was breaking or being threatened by the police, the transportation team would have vehicles ready to take people to the location and reinforce the blockade. The BBC Scotland radio station was reporting that all roads leading north to Gleneagles were backed up with no traffic passing through. Naturally, they did not mention the reason for this, and tried to hide the successful blockades behind a regular traffic update.

Coordinating from the Eco-village.

Everyone at the campsite was ecstatic and it felt like it was time to start upping the ante, which meant taking on the perimeter fence around the G8 summit. The legal march scheduled for the afternoon by the G8 Alternatives, who were often controlled by the Socialist Workers Party, had been called off by the police due to the disruption caused on the transportation system of Scotland. To their credit, the organizers decided to move forward and go ahead with the march at Auchterarder, the town nearest to Gleneagles Hotel.

Now that the stakes were raised, vans from the Eco-village began to head straight to Auchterarder rather than to reinforce the blockades. Two hours later, the news of the perimeter fence being breached at two different points reached the camp. Anarchists and Scottish socialists were tearing apart the fence and throwing pieces of it at the riot squad police. Some groups entered the G8 Summit area and were confronted by Chinook helicopters unloading hundreds of riot police equipped with dogs. At 12:30 in the afternoon, it appeared that the eight most powerful men in the world were still unable to begin their meeting in Gleneagles.

There are many lessons to be learned from the victories won at this most recent mass action of the young anti-capitalist movement. Tactically, having decentralized actions coordinated within the same infrastructure, all given the targeted locations in the same area, was an incredible strength for activists attempting to disrupt the summit. Previous mass mobilizations have failed when calls were made for affinity groups to do autonomous direct action without a strategic frame in which to act. On the night of July 5th and into the early hours of the 6th, groups in Scotland were able to scatter themselves along a geographical network of points. Working together to assess need for numbers and actions, people dispatched themselves between a multitude of different motorways and byways surrounding Gleneagles and around hotels in Edinburgh. There were threats to blockade not only the roads around Gleneagles but the roads out of the major cities of Edinburgh and Glasgow. This meant the police forces were stretched thin, having to be at Glasgow, Edinburgh, Sterling, and Gleneagles at the same time. The state was forced to provide dozens of officers to contain each small group of activists, and as affinity group after affinity group spontaneously hit the transportation corridor, the police simply could not maintain their own coordination or mass their numbers. The suicide march, which went on for miles over before reaching the highway, was a strong challenge to state control and proved to be impossible to contain even with the strongest police effort.

According to friends inside of the summit, the blockades were a throbbing migraine for the G8 and it took some delegates up to seven hours to get to Gleneagles. Suffocating their critical control with a continual barrage of activity and exhausting police numbers by using quick-moving affinity groups to the best possible advantage are tactics that allows us to call the shots on our own terms, whether it be Gleneagles, Buenos Aires, or La Paz. The rabble-rousing group behind the blockades was extremely international in character and the links formed are going to be a major pain for global capital for the years to come. As if the international anarchist force wasn’t enough, it was reported that while Bush was riding his bicycle at Gleneagles he ran into a police officer, sending him to the hospital.

September 11th reminds most of the world of New York and some of us of Santiago. There was another September 11th more then 700 years ago. On September 11th, 1297, William Wallace observed the English coming into impose their enclosure of the Scottish land. This was the day of The Battle of Stirling Bridge, where the 60,000-person English army suffered a terrible defeat at the hands of the Scottish who numbered around 10,000. The English sent two messengers to Wallace to ask for his surrender. Wallace’s reply was similar to that was given to the G8 on Wednesday by the street fighters in Stirling:

“Return to thy friends and tell them we come here with no peaceful intent, but ready for battle, determined to avenge our wrongs and to set our country free. Let thy masters come and attack us; we are ready to meet them beard to beard.”

A helicopter monitoring protesters as they approach the security perimeter.

Following Up with the Locals

In the evening of July 6, others in the camp went to a meeting with local activists. The people they met were community workers who all lived locally and would have been broadly against G8 activity. They expected hostility, but didn’t find it. It was decided that the residents of Stirling would be invited to dinner in the camp on Friday, July 8, and that some of from the camp would join the community organizers at their weekly stall downtown.

Those present from the camp wanted to find out if they could donate money to people who had had the windows of their homes broken. The residents said that besides newspaper reports, they hadn’t met anybody who knew anyone to whom this had actually happened.

Out of everyone involved in the black bloc action, it wasn’t possible to find anyone who saw damage done to private houses. One participant said that he saw an unmarked police car being trashed. Perhaps some within the press assumed this car to be owned by local inhabitants.

[a post on the Scottish Indymedia website:]

You’ve got to hand it to them…

06.07.2005 15:02

…some good has been done.

Thanks to the anti-world brigade, we have all been told we can leave work early.

I back the protesters, more protesting please…

Can you protest next Monday? I would like the day off, I have a dentist appointment.

Thanks.

Scotsman

The Blockades

In Muthill, near Crieff, a small village that had never been discussed openly as a site for protest, five people locked themselves together, blocking traffic. Thinking themselves safe, the American delegates to the G8 had located in Crieff; they had to spend hours waiting for the police to disassemble the complex blockade. Another blockade composed of a car with lock-ons inside and underneath hit the small road southeast of Gleneagles at the village of Yetts o’ Muckhart. Because the police had to spend so much time getting the Crieff blockade dismantled, this one was up most of the day. In case the delegates were re-routed around the A9, another large blockade hit the exit from Perth, and two smaller ones were set up southwest of it. The train tracks to Gleneagles were disabled by means of a compressor, with tires ablaze on both sides as a warning. The hotel was completely surrounded by blockades for most of the morning. The Canadian delegates never even made it to Gleneagles.

The original plan was to coordinate these blockades with disruption at the hotels where delegates were staying in Edinburgh and Glasgow, but this was less successful. Presumably going on the primarily urban character of recent anti-summit activity, the police had guessed that the most trouble would take place in these cities, and assembled much of their forces there. All the same, a few protesters managed to carry out their plans. Some went to the Sheraton Hotel where the Japanese G8 delegates were staying, and while hordes of police officers prevented any mass action, affinity groups blocked the road by throwing a bin into the street as the delegates climbed on a bus. Then, as delegates left the hotel with the help of the police and made their way north to the giant steel bridge connecting Edinburgh to central Scotland, anarchists blocked the road by crashing two cars into each other in a literally death-defying action.

After the initial wave of blockades, many activists remained near the routes to Gleneagles, establishing further blockades on an impromptu basis. Whenever police showed up, they dispersed into the surrounding fields, only to reassemble as soon as the coast was clear. This helped keep the roads impassable for much of the day.

The format used to shut down traffic to the G8 summit resembled the model used to paralyze San Francisco on the first day of the invasion of Iraq in 2003. Such decentralized tactics proved to be extremely effective when coordinated by a common infrastructure. Even against a vastly more powerful opposing force, small groups can gain the upper hand so long as they are highly mobile and well-coordinated and are able to muster numbers equivalent to those of their opponents at the critical points of engagement. The lack of a central directing body means that even if one group is immobilized, the others can carry on just as effectively, as the strategic framework for actions has already been established.

After blockading, many went to join the G8 Alternatives march to the fence surrounding Gleneagles. Using the disruption of traffic as an excuse, the police had announced that they would not permit the march to take place; but, to their credit, the organizers threatened to march on the US embassy in Edinburgh if the original march route was denied, and the police grudgingly let them go ahead. As soon as the march came within view of the Gleneagles hotel, a great many participants, not at all invested in the socialist organizers’ call for a submissive, law-abiding march, surged across the fence and charged forward. The police lines were not sufficient to stave off this incursion, and hundreds more riot cops had to be flown in by means of Chinook helicopters before the field could be secured again. An eyewitness from the Infernal Noise Brigade reports:

The grass was tall and deep green and I was keeping myself between the band and these lines of mounted riot police. I was doing tactical and so not carrying an instrument; as the horses approached, they were so incredibly tall, their legs buried in the barley. I could smell them, and they smelled like normal horses, but they had these beasts on their backs driving them forward, threatening us by turning them so we were in range of their back hooves. The sky was gigantic and held low-flying military vehicles, stark against the blue, and the fields stretched on forever in every direction, the horizon cut by the outlines of all these people in their battle outfits, their flags of peace or war, their cameras and clown costumes. It was terrifying, beautiful, and epic.

Police mobilizing in the field to guard Gleneagles.

Resistance in an Age of Terror

Under the cover of darkness early the following day, the police finally fulfilled everyone’s fears by blockading the camp. The more insurrectionary anarchists argued that the police blockade around the Eco-village had to be broken so activists could continue the successes of the previous day. With the police so obviously weak and the fence easily toppled, they believed one more coordinated action could shut down the summit. More pacifist elements felt that any attempt to fight through the police lines, especially now that the police would not be caught off guard as they had been the previous morning, would be a disaster; but they couldn’t propose another way to deal with the blockade.

Before discussions about the next few days of action could really commence, however, the news arrived that there had been a terrorist attack in London. It hit everyone like a physical punch in the stomach; the whole meeting came to an eerie standstill. The net effect was complete paralysis. The energy left the Eco-village, and people eventually began leaving in small groups, making their way meekly through the police checkpoint.

The bombings enabled the G8 leaders to cement their image as the defenders of Western civilization from barbaric extremists. Never mind that it was these same leaders who had moved the entire police force of London north to repress protesters instead of guarding the civilians who were killed. Never mind that it was the policies of these leaders that provoked terrorists to target British civilians in the first place. Indeed, like the destruction of the World Trade Center in 2001, the London bombing was so effective in enabling the G8 leaders to consolidate their power that one can’t help but wonder if such attacks might figure in their strategy for world domination. Could it be that these heads of state are banking on the inevitable reprisals that their activities provoke to keep their citizens in line?

The fact that the G8 protests were eclipsed by the attack in London shows that anarchists have some catching up to do to be able to act effectively in the current historical context. The successes of these protests disprove the cowardly superstition that militant demonstrations are impossible under the conditions of today’s terror war. The problem is not that resistance is impossible, it is that our resistance, however tactically effective, will not be able to attract mass participation until people see that their rulers pose as great a threat to them as the terrorists they claim to be keeping at bay.

As long as people can only imagine politics as a choice between authoritarian rulers, they will always choose the more familiar ones; we have to show that it is not necessary to submit to rule of any kind, that in fact submission to authoritarian power brings us into greater danger than opposition to it does. Every time we freeze up in the face of a terrorist attack, fearing we will appear insensitive or insane if we continue our resistance, we cede the political field to the mind-numbing spectacle of one authoritarian force versus another. We need to craft a strategy for resistance that takes into account the strategies of fundamentalist terrorists as well as the tyranny of our rulers.

We could begin by focusing on holding powers such as the G8 responsible for the attacks they bring about. It is their imperialism and exploitation, their wars for power and control, that put the rest of us in harm’s way, anyway, whether as soldiers in occupying armies or as civilian targets. Most of the protesters in Scotland focused on economic issues, such as third world debt and the erosion of social welfare programs and job security; perhaps if more anarchists had explicitly stated that they were there to stop the rulers of the world before those rulers get us all killed, their efforts would have retained their relevance and persuasiveness after the bombings, possibly even serving as a catalyst for a broader public outcry. The rage people feel about being targeted by terrorist attacks is one of the most powerful forces in the political climate today; if we could turn this against those who currently benefit from it, anarchists would quickly gain the upper hand in our struggle against state power.

Banners hang at the Eco-village after the attacks in London.

Further Reading

Shut Them Down! The G8, Gleneagles 2005 and the Movement of Movements

-

The Dissent! media policy succeeded in preventing the rise of media spokespeople—but, in the words of one frustrated activist, “When no one speaks to the media, the police just end up speaking for us!” When one of our goals is to reach and involve a lot of people, we must either establish our own means of reaching them, or else find ways to use the media to our own ends. Mass mobilizations offer an opportunity for anarchist alternatives to seize the popular imagination; we can’t afford to be outdone by reformists, or to underdo things ourselves. ↩