The story goes that the very first gathering of Occupy Wall Street began as an old-fashioned top-down rally with speakers droning on—until a Greek student (and perhaps—an anarchist?) interrupted it and demanded that they hold a proper horizontal assembly instead. She and some of the youngsters in attendance sat down in a circle on the other side of the plaza and began holding a meeting using consensus process. One by one, people trickled over from the audience that had been listening to speakers and joined the circle. It was August 2, 2011.

Here, in the origin myth of the Occupy Movement, we encounter a fundamental ambiguity in its relationship to organization. We can understand this shift to consensus process as the adoption of a more inclusive and therefore more legitimate democratic model, anticipating later claims that the general assemblies of Occupy represented real democracy in action. Or we can focus on the decision to withdraw from the initial rally, seeing it as a gesture in favor of voluntary association. Over the following year, this internal tension erupted repeatedly, pitting democrats determined to demonstrate a new form of governance against anarchists intent upon asserting the primacy of autonomy.

Though David Graeber encouraged participants to regard consensus as a set of principles rather than rules, both proponents and authoritarian opponents of consensus process persisted in treating it as a formal means of government—while anarchists who shared Graeber’s framework found themselves outside the consensus reality of their fellow Occupiers. The movement’s failure to reach consensus about the meaning of consensus itself culminated with ugly attacks in which Rebecca Solnit and Chris Hedges attempted to brand anarchist participants as violent thugs.

How did that play out in the hinterlands, where small-town Occupy groups took up the decision-making practices of Occupy Wall Street? The following narrative traces the tensions between democratic and autonomous organizational forms throughout the trajectory of one local occupation.

This text is an installment in our series exploring an anarchist analysis of democracy, which is collected in our book, From Democracy to Freedom.

Democracy versus Autonomy in the Occupy Movement: A Narrative

A decade and a half ago, I participated in the so-called “anti-globalization movement,” so described by journalists who preferred not to say “anticapitalist.” Beginning with a groundswell of local initiatives, it culminated in a string of massive riots at international trade summits from Seattle in November 1999 to Genoa in July 2001. Although I had been an anarchist for some years already, I learned about consensus process in the course of those experiences. Like many other participants, I believed that this form of decision-making pointed the way to a world without government or capitalism. We cherished the seemingly impossible dream that one day that decision-making process might be taken up by the population at large.

Ten years later, I visited the Occupy Wall Street encampment at Zuccotti Park. It had only existed for two weeks, yet it had already developed its political culture: daily assemblies, “mic check,” consensus process. This was all familiar to me from my “anti-globalization” days, though most people there clearly did not share that background.

I heard a lot of legalistic and reformist rhetoric in the course of my brief visit. At the same time, this was what we had dreamed of, our practices spreading outside our milieu. Could the practices themselves instill the political values that had originally inspired us to employ them? Some of my comrades had argued that directly democratic models could be a radicalizing step towards anarchism. The following months put that theory to the test.

Two weeks after my visit to Manhattan, I was back in my hometown in Middle America, attending our Occupy group’s second assembly. A hundred people from a wide range of backgrounds and political perspectives were debating whether to establish an encampment. It’s not easy for a crowd arbitrarily convened through an open invitation on Facebook to make a decision together. Some argued against occupying, claiming that the police would evict us, insisting we should apply for a permit first. In the nearest city, occupiers had applied for a permit but were only granted one lasting a few hours; everyone who remained after it expired was arrested. A few of us thought it better to go forward without permission than to embolden the authorities to believe we would comply with whatever was convenient for them.

A different facilitator would have let the debate remain abstract indefinitely, effectively quashing the possibility of an occupation in the name of consensus. But ours cut right to the chase: “Raise your hand if you want to camp out here tonight.” A few hands went hesitantly up. “Looks like five… six, seven… OK, let’s split into two groups: those who want to occupy, and everyone else. We’ll reconvene in ten minutes.”

At first there were only a half dozen of us meeting on the occupiers’ side of the plaza, but after we took the first step, others drifted over. Ten minutes later, there were twenty-four of us—and that night dozens of people camped out in the Plaza. I stayed up all night waiting for the police to raid us, but they never showed up. We’d won the first round, expanding what everyone imagined to be possible—and we owed it to people taking the initiative autonomously, not to reaching consensus.

Our occupation was a success. Over the first few weeks, scores of new people met and got to know each other through demonstrations, logistical work, and nights of impassioned discussion.

The nightly assemblies served as a space to get to know each other politically. First, we heard a wide range of testimonials about why people were there. These ranged from boring to fascinating, but they died out swiftly once the business of making decisions via assemblies got underway. Next, we weathered lengthy debates about whether there should be a nonviolence policy, with nonviolence serving as a code word for legalistic obedience. Thanks to the participation of many anarchists, this discussion was split pretty much down the middle, but it enabled many occupiers who had never been part of something comparable to hear some new arguments.

It was interesting to watch so many people go through such a rapid political evolution. I enjoyed the debates, the drama of watching middle-class liberals struggle to converse on an equal footing with anarchists and other angry poor people.

On the other hand, the assemblies were ineffective as a way to make decisions. After weeks of grueling daily sessions, we gave up entirely on formulating a mission statement about our basic goals, consensus having been repeatedly blocked by a lone contrarian. Some people managed to push a couple small demonstrations through the consensus process, but they attracted almost no participants. The assembly’s stamp of approval did not correlate with people actually investing themselves; the momentum to make an effort succeed was determined elsewhere.

While the nightly assemblies helped us get to know each other politically, if you wanted to get to know people personally, you had to spend time at the encampment. Standing night watch, facing off with drunk college students and other reactionaries, I became acquainted with many of the occupiers who had first arrived as disconnected individuals. It was those connections that gave us cause to be invested in each other’s efforts over the following months.

Unexpectedly, the liberals were among the most invested in the protocol of consensus process—however unfamiliar it was, they found it reassuring that there was a proper way of doing things. This emphasis on protocol created rifts with the actual inhabitants of the encampment, many of whom felt ill at ease communicating in such a formal structure; that class divide proved to be a more fundamental conflict than any political disagreement. From the perspective of the liberals, there was a democratic assembly in which anyone could participate, and those who did not attend or speak up could not complain about the decisions made there. From the vantage point of the camp, the liberals showed up for an hour or two every couple days, and expected to be able to dictate decisions to people who were in the camp twenty-four hours a day—often not even sticking around to implement them.

As a part of the minority that was familiar with consensus process yet simultaneously a denizen of the camp proper, I could see both sides. I tried to explain to the liberals who just showed up for the assemblies—the ones who understood Occupy as a political project rather than a social space—that there were already functioning decision-making processes at work in the encampment, however informal, and if they wanted to establish better relations with the residents of the encampment, they should take those processes seriously and try to participate in them, too.

After the first few weeks, the flow of new participants slowed. We became a known quantity once more. Consequently, we began to lose our leverage on the authorities. Meanwhile, it was getting colder out, and winter was on the way. Based on our experience attempting to formulate a mission statement or call for demonstrations, it seemed clear to us that if there was to be a next step, it would have to be decided outside the general assemblies.

I got together with some friends I had known and trusted for a long time—the same group that had called for Occupy in our town in the first place. We discussed whether to occupy a vast empty building a few blocks from the plaza. Most of us thought it was impossible, but a few fanatics insisted it could be done. We decided that if they could get us inside, we would try to hold onto it. But the plan had to be a secret until we were in, so the police couldn’t stop us.

The building occupation was a success. Over a hundred people flooded into the building, setting up a kitchen, a reading library, and sleeping quarters. A band performed, followed by a dance party. That night, dozens of people slept in the building rather than at the plaza, relieved to be out of the cold. Once again, I stood watch all night, waiting for the police—the stakes were higher this time, but they didn’t show up. Spirits were high: once again, we had expanded the space of possibility.

The following afternoon, as we continued cleaning and repairing the building, a rumor circulated that the police were preparing a raid. Several dozen of us gathered for an impromptu meeting. It struck me how different the atmosphere was from our usual general assemblies. There were no bureaucratic formalities, no deadlocks over minutia. No one droned on just to hear himself speak or stared off listlessly. There was no payoff for grandstanding or chiding each other about protocol.

Here, there was nothing abstract about the issues at hand. We were putting our bodies on the line just by being present; these were real choices that would have immediate consequences for all of us. We didn’t need a facilitator to listen to each other or stay on topic. With our freedom at stake, we had every reason to work well together.

The day after the raid, a huge crowd gathered at the original encampment for a contentious general assembly—the biggest and most energetic our town witnessed throughout the entire sequence of Occupy. Our decision to occupy the building, arrived at outside the general assembly, had ironically made the general assembly irresistible to everyone. Some people were inspired by the building occupation and our response to the police raid; others, who assumed the general assembly to be the governing body of the movement, were outraged that we had bypassed it; still others, who had not been interested in Occupy until now, came to engage with us because they could see we were capable of making a big impact. Even if they were only there to argue that we should “be peaceful” and obey the law, we hoped that entering that space of dialogue might expand their sense of what was possible, too.

So the assembly benefitted from the building occupation, whether or not people approved of it. But they only came because of the power we had expressed by acting on our own. It was this power that they sought to access through the assembly—some to increase it, some to command it, some to tame it. In fact, the power didn’t reside in the assembly as a decision-making space, but in the people who came to it and the connections they forged there.

Over the following week, people inspired by the building occupations in Oakland and our little town occupied buildings in St. Louis, Washington, DC, and Seattle. This new wave of actions pushed the Occupy movement from symbolic protests towards directly challenging the sanctity of capitalist notions of property. Our town saw its biggest unpermitted demonstrations in years.

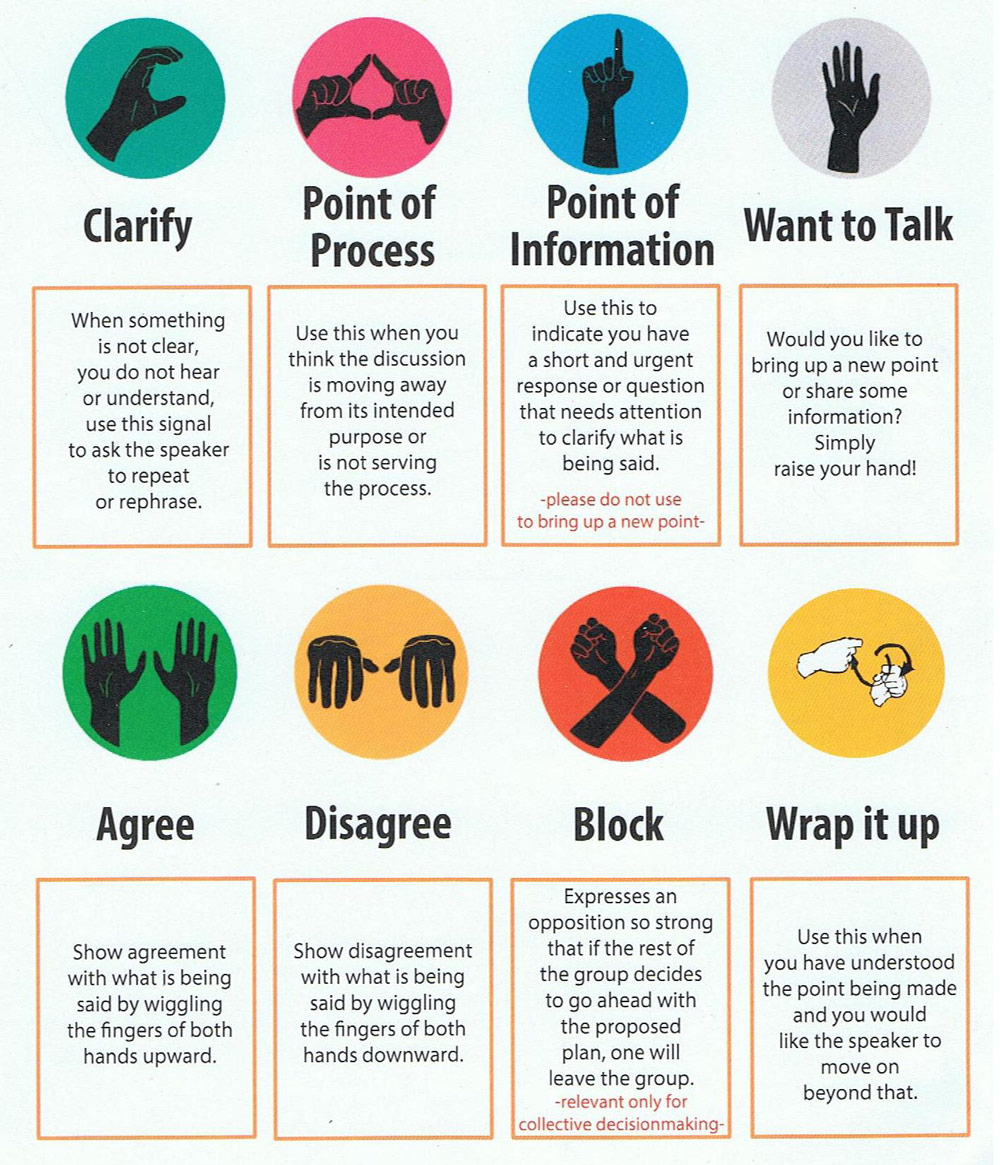

Months later, I compared notes with comrades around the country about how this mass experiment in consensus process had gone. Everywhere, there had been the same conflicts, as some people who saw the assemblies as the legitimate space of decision-making criticized those who propelled the movement forward for acting autonomously. Even in Oakland, the most confrontational encampment in the country, they never made a consensus decision to keep police out of the camp—that decision was made by individuals, independently. A friend from Oakland recounted to me how, when he prevented an officer from entering, a young reformist who had just learned the buzzwords of consensus process angrily shouted “I block you, man! I block you!” at him. In a photograph taken after the riots with which occupiers retaliated against the eviction of their encampment, someone has written on a broken window, “This act of vandalism was NOT authorized by the GA,” as if the GA were a governmental body, answerable for its subjects and therefore entitled to legitimize or delegitimize their actions.

That shows a profound misunderstanding of what consensus procedure is good for. Like any tool, power flows from us to it, not the other way around—we can invest it with power, but using it won’t necessarily make us more powerful. Every single step that made Occupy succeed in our town, from the call for the first assembly to the decision to occupy the plaza to the decision to occupy a building, was the result of autonomous initiative. We never could have consensed to do any of those things in an assembly that included anarchists, Maoists, reactionary poor people, middle-class liberals, police infiltrators, people with mental health issues, aspiring politicians, and whoever else happened to stop by at random. The assemblies were essential as a space where we could intersect and exchange proposals, creating new affinities and building a sense of our collective power, but we don’t need a more participatory—and therefore even more inefficient and invasive—form of government. We need the ability to act freely as we see fit, the common sense to coexist with others wherever possible, and the courage to stand up for ourselves whenever there are real conflicts.

As the movement was dying down, the faction of Occupy that was most invested in legalism and protocol called for a National Gathering in Philadelphia on July 4, 2012, at which to “collectively craft a Vision of a Democratic Future.” Barely 500 people showed from around the country, a tiny fraction of the number that had blocked ports, occupied parks, and marched in the streets. The people, as they say, had voted with their feet.

Anarchists all over the country made mistakes about direct democracy and the general assembly form—a mistake revolutionaries have been making for decades. It could be useful to attend assemblies, but it is not useful to be governed by them.

-Don’t Die Wondering: Atlanta Against the Police Winter 2011-2012