What I find sorely lacking in most of the discussions of veganism I encounter is any sense of economic context. Usually, the question of animal oppression is approached only in terms of compassion and prejudice: animals are exploited and destroyed, vegan activists would have us believe, simply because we see them as subhuman and are willing to abuse them in order to satisfy our greed.

I suspect that the problem runs much deeper than mere cruelty and avarice. Under capitalism, it’s not just animals that are exploited — it’s everyone and everything from farmlands and forests to farmhands and grocery clerks. The oppression of animals is just a little more obvious to us because it involves the murder of living things; but it’s not just animals that have been enslaved and transformed by our society, it’s everything, ourselves included. Without an understanding of how and why our social/economic system drives us to seek to dominate and exploit everything, we will not be able to alter the way animals are treated in any significant or long-lasting way. Capitalism forces us to evaluate our environment and each other according to market value. Under the capitalist system, every man is encouraged to ask the question of how useful the animals and people around him might be as economic resources in his competition with others. Everything becomes fair game for exploitation—because if you don’t exploit something in the rush to gain the upper hand in the free market’s “exchange of goods and services,” someone else will exploit it, and quite possibly use it to exploit you. Those who have realized this are not afraid to exploit animals or humans, to treat them as objects, because they believe that the alternative is to be treated as objects and exploited by others themselves. In this way, capitalism divides us against each other and spurs on our destruction of the environment.

When I walk through the aisles at the supermarket, looking at all the products for sale around me, perhaps I can tell which ones are manufactured from the exploitation of animals, but I can’t tell which ones — if any — are manufactured without exploiting anyone or anything. That is one of the biggest drawbacks about our modern mass-production/distribution/consumption economy: by the time the product has reached you, it is virtually impossible to tell who made it, how it was made, what it was made from, or where it has been. Toilet paper, canned kidney beans, and athletic shoes all sit on the shelves next to each other, as if they appeared out of the air, and it would be a long hard struggle to track down any real, sound information about the origins of any of them. But there are some things I do know, though, even if I can’t research the life story of each individual packet of ramen noodles: there are migrant workers in this country who are underpaid and mistreated, there are corporations (like Pepsi) known for supporting totalitarian governments that mercilessly destroy human life, there are shoe manufacturers (like Nike) that underpay and mistreat foreign workers, there are companies (like Exxon) whose policies result in permanent damage to the environment. So the idea that you can be sure that your dollars are not financing anything inhumane or destructive just by examining the ingredients of a product and ascertaining that it includes no animal products strikes me as absurd. There are a thousand other kinds of oppression, just as outrageous as animal oppression, that keep the wheels of our economy turning, and there is no reason to be less concerned about any of them than about animal oppression.

It seems to me that the long term solution to this problem is not just to buy vegan food and animal-friendly products. If we want to change the conditions that have resulted in the widespread destruction and exploitation that characterize our world, we must work towards a complete overhauling of our economy — we must somehow escape from the vicious cycle of capitalism. The only way to fight capitalism is to undermine its assumptions: that happiness is having things (“the one who dies with the most toys wins”), that there is no realistic way to work with each other rather than competing against each other, that any other economic system means some kind of slavery (like the former communist U.S.S.R.). If these assumptions are untrue, which isn’t hard to imagine, then it should be possible for us to create a different kind of economy and a different kind of world. If people start to conceive of happiness as the freedom to do things rather than have things, if they decide that they enjoy being generous more than being selfish, if they can imagine that it might be possible to create a society in which we work together for the good of everybody rather than against each other and the environment for (what advertisements claim is) our own good, then capitalism will ultimately fall.

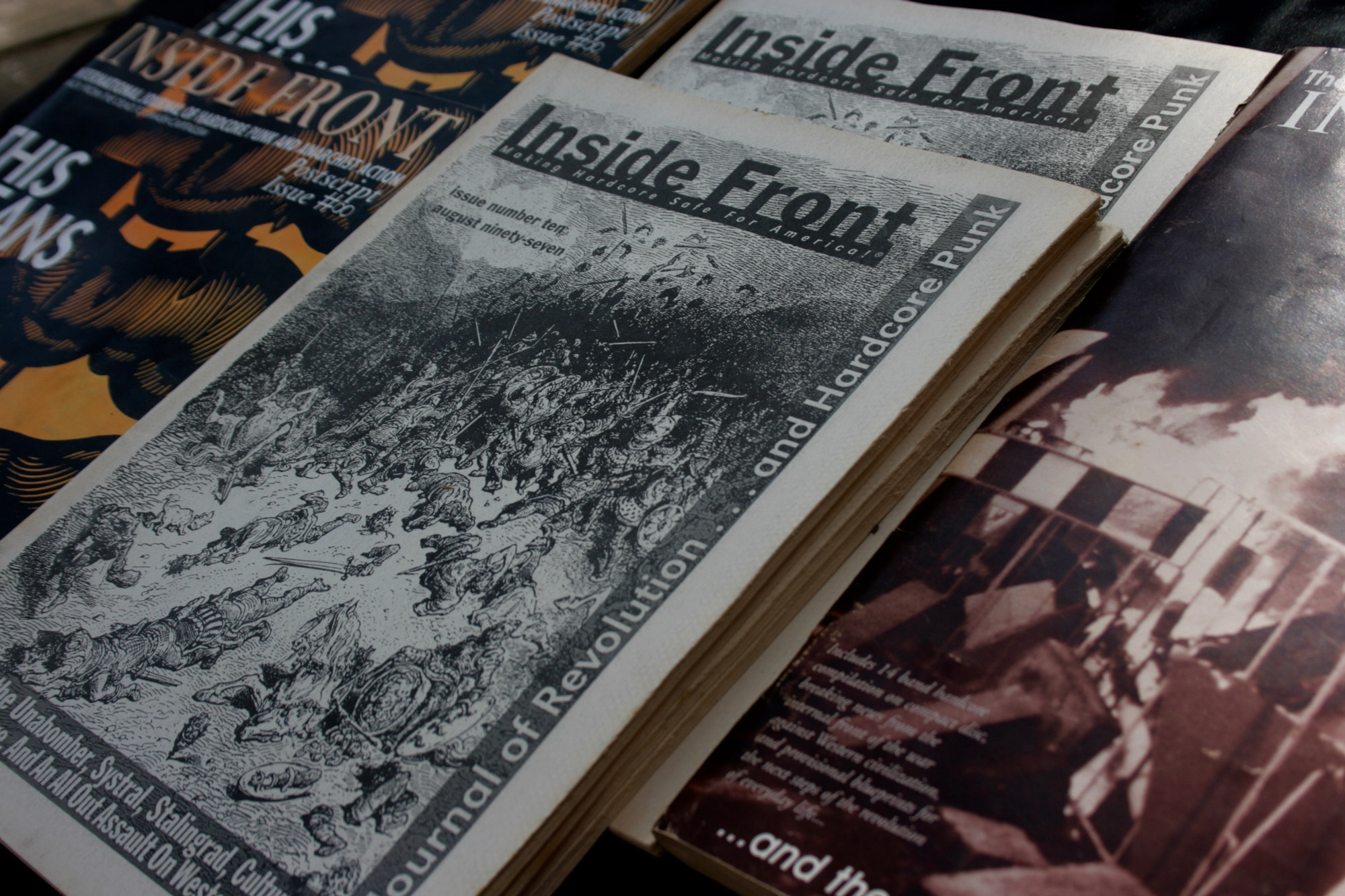

In the meantime, rather than practicing veganism, I practice “freeganism.” I know that as long as I participate in the mainstream economy, whether I am buying vegan or non-vegan products, I am supporting the corporations which represent world capitalism. So rather than just buying animal-friendly products, I try to purchase as few products as possible. I’ve written about this in earlier issues of Inside Front: it is possible, through thrifty living, creative “urban hunting and gathering,” and projects like Food Not Bombs, to survive without contributing more than a minimal amount of money or labor to the mainstream economy. Anything I can get for free at the expense of the exploiting, oppressing capitalist system is a strike against that system, while purchasing vegan food from Taco Bell (which is owned by Pepsi Co.) is still putting money into the hands of an oppressive, exploiting corporation. I live off of whatever resources I can scrounge or steal from our society, trying to avoid animal products when I can, but concentrating above all on keeping my money and labor out of of their hands. A willingness to pump money into the mainstream economy, which is responsible for the oppression of animals and humans and the destruction of the environment, through consumer spending (on fashionable athletic clothes, for example), is not compatible with the professed goal of most people who follow a vegan diet, which is to end the exploitation of animals. That’s why it strikes me as ridiculous that so many vegan activist bands like Earth Crisis are willing to perpetuate fashion consciousness in hardcore by selling so much merchandise — and by speaking only about human cruelty rather than criticizing consumerism in general, they ignore the real causes of animal oppression.

There are some great things about veganism, by the way. First of all, if you can’t bear to put anything into your body that was actually made from the corpse of another living being, veganism is a way to avoid that (although it DOES NOT magically confer the “innocence” of animal exploitation that hardline morons claim for themselves, as my discussion of capitalism and other forms of oppression should make clear). Also, it gives you a different relationship to the food you eat than most of us have: it makes you consider where it came from and what’s in it, rather than just taking it for granted, and it also will probably make you a better cook! And finally, it brings up the issue for everybody. When you won’t eat food unless you know what is in it, it forces the people around you to think for themselves about what is in the food and how it got there. In that way, veganism does more to change the world than writing lengthy political responses to letters ever could: it brings up important questions in everyday life and forces people think about questions that they wouldn’t otherwise encounter.