Early on May 28, 2013, a bulldozer arrived in Gezi Park, at the center of Istanbul, and began uprooting trees. Thousands flocked to the park in response, clashing with the police and catalyzing a movement that spread around the country in defiance of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP). Today, as Erdoğan takes advantage of Turkey’s current leverage within the North Atlantic Treaty Organization to plan another invasion of Syria, it is important to remember that he had to suppress powerful social movements in Turkey in order to cement control. Such social movements still represent our best hope for peace and social change—in Turkey, Syria, and all around the world.

The following text originally appeared in Rolling Thunder in early 2014. The author has added an introduction penned this week. For more on Turkey, you could start by reading about the background of Kurdish resistance or the roots of Turkish fascism.

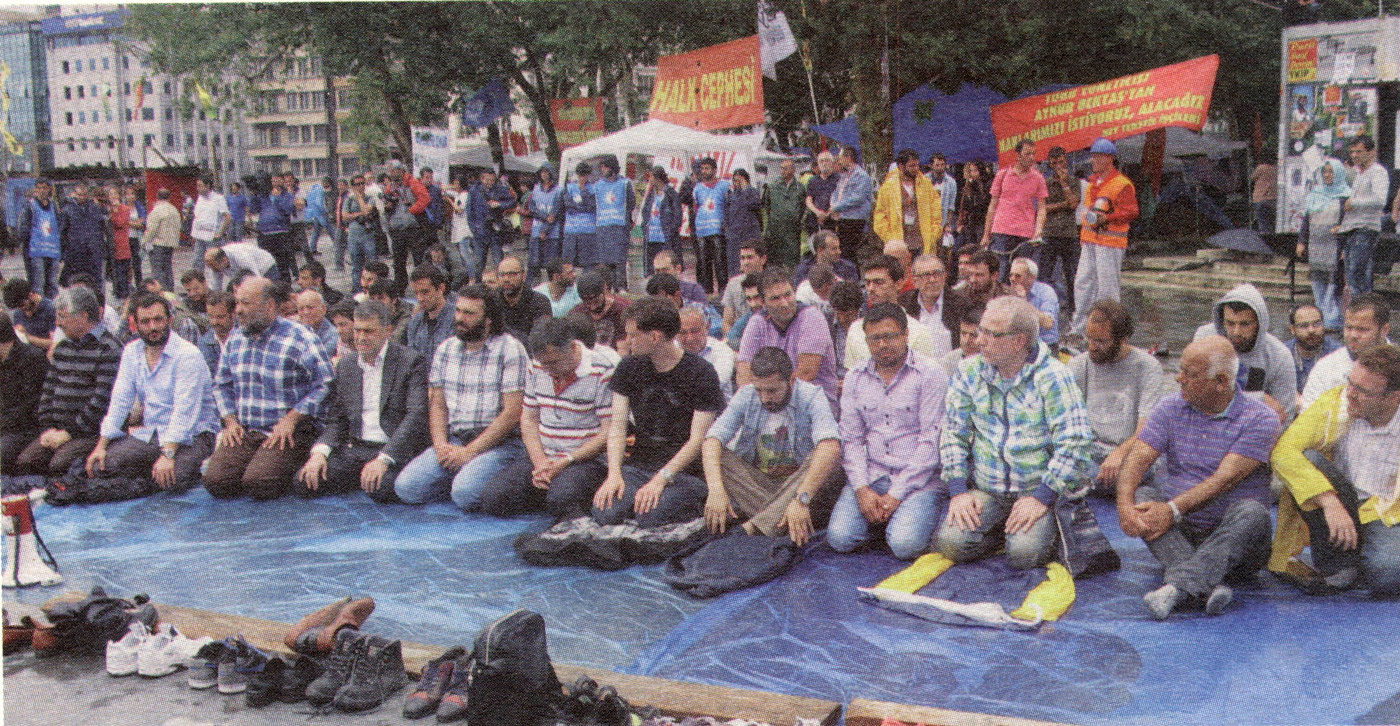

The Gezi Park uprising, June 2013.

Introduction: Looking Back on the Gezi Uprising from 2022

The memory of Gezi is vivid and fresh. It’s as if the barricades went up just last month, not nine years ago. I suppose that’s how you can distinguish a truly historical moment from ordinary run-of-the-mill moments.

What started as a last-ditch effort to protect a public park in the heart of Istanbul accelerated rapidly into an uprising that spread throughout the country, becoming the most widespread and largest movement Turkey had ever seen. From its practices within the occupied park to the humor scribbled on every building, Gezi was unique, a dream realized for any anarchist or leftist radical.

Although the memory is fresh, it is punishingly bittersweet. Looking back on the joy and hope we felt in the streets that June, I wonder—was it naiveté or optimism of the will that led millions to chant “This is only the beginning”?

In hindsight, it was indeed a beginning. But it was not the beginning of the liberation we tried to bring about. Instead, it was followed by a series of counter-revolutionary measures against everything that Gezi stood for.

How much counter-revolution can you fit into a decade? Let’s look at the five fronts on which the reaction has advanced in Turkey since 2013:

1. Consolidation of Power

Gezi was one of many factors that precipitated a falling-out between the two factions within the Turkish brand of islamic neoliberalism, identified with the figureheads Tayyip Erdoğan and Fethullah Gülen. After the rift between them widened, the Gülenist cadres within the armed forces launched an unsuccessful coup attempt against Erdoğan on July 15, 2016. The fallout from this rift between those in power has reverberated throughout Turkey. Erdoğan’s counter-attack was comprehensive; he took advantage of the coup attempt to arrest and imprison all of his opponents, including many of the actors within Gezi. Those who have avoided imprisonment have been blacklisted, lost their employment, and became public targets via the throughly AKP-controlled media channels.

2. Targeting Solidarity between the Kurdish Movement and the Turkish Left

The Gezi uprising was a rare moment—perhaps the only one in living memory—when you could see a Turkish nationalist and a PKK [Kurdistan Workers’ Party] supporter fighting on the same side of the barricades against a common enemy. The AKP regime rightly identified this as a threat to its existence; arguably, it could threaten the existence of the Turkish state-building project as a whole. The AKP has attacked this solidarity with extreme violence and repression while intensifying the war against the Kurdish movement in Turkey and Syria and also, recently, in Iraq. For now, the prospect of solidarity between the Turkish left and the Kurdish liberation movement appears distant. Peace caravans and demonstrations organized in solidarity with Rojava were bombed by Islamist mercenaries under the observation of Turkish intelligence services. The leaders of the HDP (Peoples’ Democratic Party), a project explicitly aimed at establishing bonds between the the Kurdish liberation movement and the Turkish left, have been thrown in jail along with thousands of their members. The complete suppression of the HDP is almost a foregone conclusion at this point, the date of it to be determined by Erdoğan’s political calculations.

3. Wealth Transfer

Gezi’s implicit demands were the removal of Erdoğan and his AKP regime—but at the onset, the politics that drove the defense of the park were shaped by a demand for “the right to the city.” According to some figures, the privatization overseen during the AKP regime amounts to 62 billion dollars and the public land that was sold comprises 75,000 acres. The plunder of public space and resources has accelerated over the past decade as privatization and land development continue to run rampant. Over the past five years, the Turkish lira has lost 75% of its value against the dollar, with the pace accelerating to a loss of 44% last year. Estimates of inflation range between 25% and 70% depending on who is crunching the numbers. Any way you look at it, the currency is at the edge of collapse at the expense of working people. One strategy of survival is to maintain loyalty to the AKP to secure gainful employment and skim off as much as possible. At the top, the AKP cadre and large holding firms close to them have been adding to their fortunes by transferring any remaining wealth to their pockets.

4. Restructuring State Institutions, Intensifying Repression

Alongside the post-coup purges, Erdoğan has been restructuring state institutions including the universities, the governance of charitable organizations, and—most crucially—the judicial system in order to ensure that they all do his bidding. The latest fruits of this restructuring are the convictions of the alleged organizers of the Gezi after a lengthy show trial. Eight people have been handed sentences ranging from 18 years to life for supposedly organizing the Gezi uprising. For those of us who lived through the spontaneous movement that erupted in Gezi, this is a laughable claim: it was a festival of resistance, a carnival of liberation exceeding anything anyone could have organized. Today, it is nearly impossible to even have a peaceful march in Turkey without the police immediately surrounding, beating, and arresting you. The only radical constituent of the Gezi movement that is still able to wield power in the streets is the women’s movement, with their annual March 8 marches and efforts to organize against patriarchal violence.

5. Paramilitary Formations

The AKP’s involvement in Syria has enabled it to form tight links with a variety of jihadist organizations. They have been training and arming groups like al-Nusra, hybridizing them with their homegrown equivalents and opening up Turkey as a safe haven for Islamists. Of course, these favors will be called in when the time comes. The aforementioned suicide bombings and the various paramilitary formations operating in Kurdistan offer an indication of what that might look like. The existence of these armed groups melding Turkish nationalism with Islamism and overlapping with the military and police represents a real threat to all stripes of the Turkish opposition, from revolutionaries to liberal democrats. Even rumors that the paramilitaries might take action have a chilling effect on those attempting to organize against the AKP and Erdoğan.

Gezi Park, seen from above.

Today, we are waiting on the next presidential election—an election that many of us are counting on as what might be the last chance to get rid of Erdoğan, an election in which the HDP and its sympathizers will once again act as the decisive bloc. It feels momentous, and Erdoğan is indeed losing strength as some members of his cadre jump ship one after another. Yet despite the importance of this upcoming vote—the actual date of which remains to be determined—this is all strangely familiar.

In fact, we’ve been here before. For the past ten years, there has always been an election on the horizon that people hope will deal a death blow to Erdoğan. Since Gezi, there have been no less than six of these elections, ranging from a referendum to presidential, parliamentary, and mayoral elections. Some of them were repeated until the “correct” result was delivered. Perhaps this is the counter-revolutionary maneuver that is the most painful. The spirit of direct action and prefigurative politics has been crushed through Erdoğan’s shrewd consolidation of power and brutal repression—leaving us to put all our hope into electoral politics. Once we were fighting for the beginning of a revolution; now we are fighting for the end of our despair.

Of course, no-one saw the Gezi uprising coming. In retrospect, it shared common threads with the momentum and tactics that produced the revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt, the plaza occupations in Spain and Greece, and the Occupy movement in the United States—but at the time, from where we were standing, it took us by surprise. Similarly, many of the ominous developments we see in Turkey are variations on themes that we also see playing out in Russia, the United States, and elsewhere around the world. As internationalists, we must continue to learn from each other’s struggles and tactics and remember that solidarity is our most powerful weapon against the disease of nationalism.

Almost a decade on, as another wave of unrest slowly sweeps back and forth from one side of the planet to the other, the Gezi uprising can serve as a reference point for the high-water mark of the previous wave of rebellion. It might also inform us as to what it will take to surpass it.

One lesson: you might unexpectedly find yourself at the beginning of something momentous. The more prepared you are for that moment, the more likely it will be that you will be able to help shape what that something will become.

June 11, 2013, Taksim Square. “In Seattle, we wrote the legal number on our arms in marker to call a lawyer if we were arrested. In Istanbul, people wrote their blood types on their arms. I hear in Egypt, they just write their names.”

“Addicted to Tear Gas”: The Gezi Resistance

The remainder of this text was completed at the beginning of 2014. For a day-by-day account of the uprising, start here.

Timeline

May 27 – Bulldozers arrive at Gezi Park to remove a few trees as part of the government’s development of Taksim Square. A few dozen friends respond immediately and stop the trees from being removed, starting an encampment that grows tenfold in each day that follows.

The pepper spraying of the woman in the red dress on May 28 produced an iconic image of the resistance, which spread through social media.

May 31 – Having been brutally evicted from the park by riot police, a few hundred people attempt to hold a press conference at Taksim Square but are attacked with water cannons. Social media is buzzing with news of the attack. The neighborhoods around the square explode in spontaneous revolt; street fighting continues until early morning.

June 1 – The Gezi Resistance recaptures the square and the park from the police and starts to set up an occupation; thousands arrive with tents in tow. The clashes spread around Istanbul and Turkey as people march in solidarity with those defending Gezi Park.

June 8-9 – The neighborhoods around the square have been totally transformed by graffiti and barricades, while an autonomous commune takes shape within the park. On June 8, fans from the three major soccer clubs of Istanbul converge on the square for a dramatic show of force. They have put aside previous hostilities towards each other, becoming the principal fighting force against the police, especially the fan club of Besiktas, Carşı. On June 9, there is a much larger demonstration of hundreds of thousands, this time more leftist in character. People claim this is the largest crowd the square has ever seen.

June 11 – The police launch an operation at 7 am to take back the square. Fierce clashes continue into the night, but ultimately the police hold the square.

The evening of the police operation to clear the square, June 11. A call was put out to converge on the square. While the numbers were at their highest, the police launched a barrage of tear gas. It was a miracle that another fatal stampede didn’t occur, reprising the tragedy of 1977.

June 15-16 – Having occupied the square for the past four days, the police use it to stage the eviction of Gezi park at 7 pm. The park is quickly cleared, but Istanbul explodes as the city tries to make its way to Taksim. Demonstrators cross the Bosporus bridge for the second time in two weeks. The fighting goes on well into the next day.

June 16 – Prime Minister Erdoğan makes his appearance at a massive rally in Istanbul in the style of a conqueror while clashes still continue across the city. He continues to defame, insult, and belittle those in the street.

June 18 – Through the initiative of Carşı, forums begin to take place in dozens of parks in different neighborhoods around the city. They are local in flavor, emphasizing various issues that impact the neighborhoods.

June 30 – The Gay Pride march is larger than it has ever been, with 50,000 attending. It is as much a march for the Gezi Resistance as for the LGBT community in Istanbul, pointing to the convergence of many struggles through Gezi.

July 8 – The beginning of Ramadan, the month of fasting for Muslims. The Anti-Capitalist Muslims mark the month by organizing people’s iftars, the breaking of the fast at sunset, in public places on newspapers spread on the ground.

Some of the Participants

Carşı

Carşı is the main fan club of the football team Beşiktaş, with a 30-year legacy behind them. Despite having the Circle A in their logo (previous versions also carried a hammer and sickle), they do not identify as anarchists; the circle A simply represents their “rebel spirit.” Carşı defines itself as apolitical in the sense that it does not support any political party or ideology, yet they have a history of participating in May Day and anti-war demonstrations and opening political banners in their stadium. One of their main slogans is “CARŞI: Against everything, including itself!” Carşı gained a lot of respect during the resistance both for their bravery in street fighting and by providing a space for the soccer fans of all three major Istanbul clubs to unite against the police, putting aside their previous mutual hostility.

On June 8, fans from the three main clubs in Istanbul converged on Taksim Square for a celebratory show of force.

Anarchists

Anarchists were integral to the Gezi Resistance, providing the forms of prefigurative politics that shaped the commune in the park and participating at the forefront in fighting the police. Beyond the smaller crews, the most organized anarchist group was DAF—Revolutionary Anarchist Action1—although the sudden emergence of the movement shocked them as much as everyone else. They set up their space right at the entrance with the Anti-Capitalist Muslims on one side and the Kurdish BDP and PKK on the other. Running three social spaces in Istanbul, they were able to provide logistical support in self-organization and also organized workshops and events on the anarchist struggle worldwide.

LGBT Blok

The LGBT community outdid itself at every step as one of the shining constituents of the Gezi Resistance. They held down a section of the occupation at the park and fought on the barricades during some of the most crucial battles, blowing minds in a traditionally macho and homophobic society where queer people are regarded as passive and cowardly despite every example to the contrary. The annual Pride week occurred right after the eviction of the park and served an important role in keeping people in the streets. The Pride March drew more people than ever before: the first example of how movements in Turkey can count on much larger numbers and energy thanks to Gezi.

Anti-Capitalist Muslims

With their slogan “Allah, Bread, Justice,” the Anti-Capitalist Muslims challenged both the Islamist neoliberalism of the AKP and the conservative secularism of some within the Gezi Resistance. They emerged during the May Day celebrations of 2012, drawing on a current of thought leading back to the Iranian Islamic Scholar Ali Şeriati. They organized Friday prayers and other Islamic celebrations at the park in an effort to combat the “pious vs. sinful” polarization pushed by Erdoğan. One of their most successful initiatives occurred at the onset of Ramadan, the month of fasting, which began a few weeks after the eviction of Gezi. As a response to the government-sponsored lavish feasts to break the fast at sundown, they organized “earth tables.” Throughout the month of Ramadan thousands of people around the country broke their fast together upon newspapers on the ground, sometimes directly in front of water cannons.

Anti-Capitalist Muslims holding Friday prayers at Gezi Park.

Leftist Unions

DISK and KESK are the two trade union confederations on the left that emerged from the struggles of the 1970s and ’80s. DISK was the main organizer behind the 1977 May Day demonstration in Taksim Square that became the site of a paramilitary massacre. Both confederations supported the Gezi Resistance, attempting to supplement it with calls for strikes. Although two such strikes did happen during the uprising, they were completely ineffective in sabotaging the national economy; once again showing the powerlessness of traditional-form trade unions in the modern class-composition landscape.

Müşterekler (Our Commons)

An umbrella group representing various city-based struggles in Istanbul. Many of their members belong to a budding anti-authoritarian Left scene involved in immigrant rights defense, ecological struggles, and fighting the enclosure of the city. They were involved in defending Gezi Park from development long before the struggle blew up, and were the most organized logistical group within the park due to their already extensive network among those interested in right-to-the-city activism. They attempted to push the movement further by reclaiming a derelict parcel of land within the barricaded zone. Like many other groups, they emerged from June 2013 much stronger, with new projects including a weekly news bulletin and a pirate radio station, Gezi Radio (www.geziradyo.org).

A map of the occupation of Gezi Park.

A map of central Istanbul, with the Bosphorus to the east.

Addicted to Tear Gas

I look around and can’t fathom what has become of this place, of the streets where I grew up. Where I went on my first date and went to my first protest, where I had my first drink sitting on the curb, where my friends and I periodically got into trouble. It was all on these streets of Beyoğlu. Now, we are thousands and thousands taunting the police in unison, chanting for them to gas us so we can get going.

And finally it arrives: the canisters are flying in one after another. We are so used to it by now that it is almost a relief to smell the gas; our first reaction is to cheer the arrival of the burning sensation. There’s no panic and no one is running. We make a slow retreat of a few dozen meters before the materials to construct the first barricade of the evening are brought to the forefront. This is the beginning of a two-day battle to take back the square. We’ve all lost count, but probably the fifth or sixth such battle since the end of May.

The AKP government, with Recep Tayyip Erdoğan at its helm, took power in Turkey ten years ago and embarked upon itslong-term project of transforming the country into an exemplary Islamic neoliberal stronghold. The latest stage of Sultan Erdoğan’s vision has been a concerted attack on Istanbul through a number of urban transformation projects that would enclose the remaining public spaces in the city. One of these was to destroy Gezi Park to make way for a commercial shopping complex in the heart of the city, Taksim Square, effectively erasing the long history and culture associated with that space.

Two months prior, in April, there were only about 300 of us at Gezi as part of a day-long festival to fight the development of the park. At that time, my comrades and I acknowledged that we were in yet another losing fight, after having been through so many. There was some energy at the festival, but we were mostly just the usual suspects. It was hard not to be cynical. At least we made a stand, we told ourselves; hopefully history will remember that some were opposed to what Istanbul was slated to become. It was just as depressing as every previous moment of the five years of AKP rule. It felt like there was no space to move, even to breathe, as Erdoğan consolidated his grip on our lives.

Although at home it felt more and more claustrophobic, the pundits of politics and economy observing from afar kept glorifying the successes of the Turkish miracle. “More than 10% annual growth rate!” “Look at Greece and Spain, Turkey is doing amazing!” Yes, Turkey has been spared the austerity measures that have been implemented in countries such as Portugal, Spain, and Greece, but this has been the result of another crisis-fighting strategy: extreme urban development through the enclosure of the city. Although initially hit by the financial crisis in 2008, the AKP government was able to keep full fiscal blowout at bay by attracting foreign liquid capital in a scheme intrinsically tied to urban development projects such as the destruction of Gezi Park.

As I observed the hundreds of thousands around me in Taksim Square, I couldn’t help imagining that this might be the crucial turn from the austerity riots of the past years. Gezi was—at least in part—an uprising against the enclosure of the city in a time of an economic boom; it was not a protest demanding a return to the Keynesian dream. That said, the clock is ticking on the Turkish economy; the foreign debt holders will come knocking on the door soon. One can only hope that a population having struggled during boom-time development won’t settle for a return to liquidity once a financial crisis brings about austerity.

Burnt media vans form a makeshift barricade in front of the Ataturk Cultural Center, draped in the banners of leftist organizations and other groups.

Recovering from Left Trauma

Taksim Square is a heavy place for my parents’ generation. My uncles and aunts have told me the story of the Taksim Square massacre on May Day 1977, when snipers on rooftops and the ensuing panic killed 34 people. Since then, Taksim Square has been the hotly contested zone of May Day celebrations; many of the demonstrations of the past five years have become street battles to take the square. Despite the ritualistic nature of these protests, they were instrumental in injecting life into a Left that had found itself in a rut, powerless.

At first, my relatives hadn’t wanted to talk about the old militant student movement, though they had been integral to it. They claimed to have moved on from that period of their lives. But it was clear to me that rather than having moved on or even sold out, they had been crushed by the successive military coups of 1971 and 1980. Thousands of leftist students were rounded up, imprisoned, and tortured by the military regimes. In addition to dozens of extrajudicial paramilitary killings, military tribunals hanged more than 50 people. The trauma of the iron fist still hangs over the society in Turkey and has been blamed for the “apolitical” culture of my generation, those born in the 1980s and ’90s.

Taksim Square on May Day 1977, the day of the massacre of 34 people.

Cursed by what preceded it, this apolitical generation created as if out of thin air the most defiant, diffuse, and long-lasting popular uprising in the history of the country. Older leftists are still trying to wrap their heads around this. The joyful rebellion did not fit into their stale frameworks; it did not compute with their Trotskys and Lenins.

This was the beauty of the Gezi resistance. That nobody saw it coming. Not one person or group in Turkey can claim with a straight face that they predicted what transpired at the end of May and into June. The euphoria that dominated the streets of Istanbul had a lot to dowith the unexpectedness of the revolt. Millions of people had their wildest wishes fulfilled overnight as if by a magical insurrectionary genie. Isolation and depression evaporated as people found each other in the tear gas.

Barricade number 4 on Inonu Caddesi, with the Bosporus Strait dividing Europe from Asia in the background. This barricade was named for Abdullah Cömert, killed on June 3 by a tear gas canister shot at his head in the southeastern city of Hatay.

Commune

Gezi Park was a beautiful commune for almost two weeks. Spontaneity and autonomy were the rules of the game; after the park was retaken, the first tents went up with the initiative of small groups of friends. The whole park rapidly filled with tents to sleep in and dozens of larger structures hosting almost every single leftist or activist group. Mutual aid was the order of this utopia. Starry-eyed old-timers and fresh militants were living a dream come true. Leaving their normal existence behind for the time being, people who had never imagined a world without police were impressed to discover a more harmonious society in the absence of the state.

German pianist David Martello brought his piano to the barricades on June 12, 2013, providing inspiration and encouragement to all who were tensely awaiting the next police attack.

The encampment at Gezi Park bore some similarities to the experience of Occupy in the US. It was an experiment in self-organization: free stores (called Revolutionary Markets), libraries, a permaculture space, workshops, multiple kitchens, a medic tent, media production zones, and cultural events were part and parcel of the space. Yet in other respects, it was totally different from Occupy.

For example, there were no general assemblies or decision-making processes apart from those organized by the constituents of the camp in their smaller affinity or organizational groups. The central podium was an ongoing open-mic where people were free to speak as they pleased and some larger concerts and film screenings took place.

A library in Gezi Park during the occupation.

Despite the absence of a centralized decision-making body, the camp was home to many different organizations in addition to the individuals and groups of friends who were also there. The occupation resembled an open-air fair of Left, revolutionary, and identity-based groups. Each group eventually carved out a little space where members would camp and congregate.

This was especially the case while the square itself was occupied. Almost every far-left group opened up a tent with their flags flying on top. At one end of the square looms the Atatürk Cultural Center, which was adorned with dozens of banners representing many of the same groups camped out in the square and the park. What a slap in the face this must have been for Erdoğan, who had unleashed police violence for years every May Day to prevent rallies of a few hours. This surreal landscape was refreshing in that it showed a rare moment of unity among groups that evolved through sectarian split after split, stretching back to Turkey’s militant-leftist 1970s. However, it was dismaying that the pissing contest between organizations promoting their names and logos continued even in these circumstances.

The Gezi occupation also differed from Occupy in class composition. While in the US, many of the occupations became de facto homeless encampments, this was not the case in Istanbul. Perhaps because the occupation broke out at the end of the school year, during the day the occupiers were mainly people in their 20s—a budding white-collar workforce slated for the malls and business plazas of AKP’s future. This changed at the end of each workday when thousands of older people passed through until the late hours of the evening.

Critiques have been leveled at the Gezi Resistance for being too nationalistic in tone. While this was partly true at the onset of the uprising, it was quickly transformed by the participation of Kurdish groups. The Peace andDemocracy Party (BDP), the political party of the Kurdish struggle, claimed the space to the left of the entrance. Kurdish youth raised the flag of the PKK and portraits of their leader Abdullah Öcalan, imprisoned in a Turkish island prison since 1999. For those who remembered the bloody 1990s, when the majority of the 35,000 deaths from the civil war occurred, it was surreal to see the face of public enemy number one flying on flags over Taksim square. Up until recently, politicians would not even dare speak Öcalan’s name in public, instead referring to him as the “head of the terrorists.”

Every night, the commune transformed into a massive party and celebration. Huge circular halay dances with hundreds of Kurds singing their songs of liberation occurred at the entrance; deeper inside the park, participants consumed copious amounts of alcohol. This public drunkenness expressed defiance of the AKP and its policies of piety, but it also generated controversy, as some from the encampment wanted a more serious and less intoxicated resistance and others thought it inappropriate to be partying while comrades were still fighting the police in Ankara and elsewhere in Turkey—even in other Istanbul neighborhoods such as Gazi.

“Freedom for the headscarf and for alcohol!”

During the taking of the square and the weeks that followed, the air was thick with the excitement of a city in resistance. Indeed, “resistance” became the assumed name for what was going on; those on the streets saw themselves as part of a resistance movement against the AKP, its vision for Turkey, and its police state. This resistance was expressed in the creative energy, wit, and humor unleashed upon the walls of Istanbul. The liberated zone was visually transformed, thanks in part to street vendors who seamlessly switched from selling their usual fare of sunglasses, clothes, and tourist schwag to spray paint, helmets, and gas masks.

Wall space ran out; you had to wander around searching for a place to throw up your most recent witty slogan.Istanbul jam-packed the streets with obscure references to popular culture, internet memes, and nose-thumbing at the government. Word plays celebrated the ubiquitous tear gas:“ Does it come in strawberry?” Erdoğan’s statements were flung back at him, such as when he said each woman should bear three children: “I’m gonna make three kids and have them jump you.” Another hilarious quip waited around every corner: “Tayyip Winter is Coming,”2 “We’re gonna destroy the government and build a mall in its place,” “Incredible Halk,”3 “You weren’t gonna ban that last beer,”4 “Everyday I’m Chapuling,”5 and on and on for kilometers.

“Until you run out of gray paint!”

The takeover was so complete that even some of the non-sympathetic business establishments had to comply or suffer mob justice. One of the owners of a döner kebab stand at the entrance of Istiklal Avenue off of Taksim Square made the mistake of posting on Facebook about the “dogs” who had taken over and his desire to live in a Muslim country. His restaurant was reduced to rubble moments after and the board of his company had to fire him. Other businesses that did not demonstrate solidarity with the resistance were repeatedly pressured and taunted. Even Starbucks Turkey, having received some heat for not assisting protestors, had to issue a press statement expressing that it was with the resistance and would always provide support.

One of the owners of a döner kebab stand at the entrance of Istiklal Avenue off of Taksim Square made the mistake of posting on Facebook about the “dogs” who had taken over and his desire to live in a Muslim country. His restaurant was reduced to rubble moments after and the board of his company had to fire him.

The fact that many from the bourgeoisie supported the uprising underscores the central contradiction of the movement. Members of the old-guard secular and liberal bourgeoisie appeared to embrace the Gezi Movement—most notably the Koç Group, one of the few family brand-name dynasties in Turkey. They went as far as providing infrastructural support by opening up their franchise of the Hyatt alongside the park to serve as a makeshift hospital. Mobile telephone providers brought cell phone transmission vans behind the barricades in orderto facilitate the ever-increasing traffic of text messages and tweets. Ironically, they had to hang banners reading “This vehicle is here so that you have reception” as insurance against arson.

How could the interests of a faction of the bourgeoisie converge with those wanting to stop development in Istanbul? This was a product of an intra-ruling-class conflict that had been brewing for years between green (Islamic) capital, under Erdoğan’s favoritism and facilitation, and the old-guard secular capitalist class that had been sidelined and saw the Gezi uprising as an opportunity. It also reflected the desire to be part of a movement to preserve the individual freedoms and rights of modernity, recently under attack by the Islam-tinted neoliberalism of the AKP. The fact that a part of the ruling class of Turkey supported the Gezi movement points to its success at becoming all-encompassing and also its failure to become an anti-capitalist force, despite the massive number of anti-capitalists involved.

“Tayyip [Erdoğan] blocked us on Facebook!”

Barricades

All of this transpired behind dozens of barricades set up around the liberated zone of Taksim and the park. On one of the main avenues leading into the square, Inönü Avenue, there were 15 separate barricades constructed from bricks, construction debris, busses, cars, rebar cemented down to point outwards, trash containers, and everything else. Constructed from materials passed hand-to-hand by human chains of fifty or more people, these barricades stood many meters high.

As in other cities where barricades have stood consistently, such as Oaxaca where in 2006, they were maintained for months, the barricades developed their own rebel culture. Crews of mostly younger kids or leftist militant youth claimed barricades for their own with a sense of pride and conviction. Little tents and squatted spaces storing rocks and bottles near certain barricades also provided shelter for their guardians to rest. These were the outliers, the barricades at the edge of the commune. The more central ones had been claimed with banners and flags in the leftist pissing contest.

Clearing the Square

I am woken up by a comrade who tells me that the police are in the square. I rush to get there. I run across the barricade of the Socialist Democratic Party (SDP) at the edge of the square, a few hundred meters from their offices. It’s a massive metal structure made of scaffoldings, concrete barriers, and other material scavenged from construction sites. Molotov cocktails are being tossed by a handful of people in front of the barricade, behind a shield that reads “SDP Public Order Enforcement.” From the higher vantage point of the park, hundreds of people are watching this unfold as if at a soccer match, cheering when a Molotov explodes on the advancing water cannon and booing when the cannon attempts to ram through the barricade. A few hours later, the media posts pictures of those tossing the firebombs and the twitter feeds light up with conspiracy theories about how they are actually police provocateurs. The evidence? A bulge beneath one of their belts—supposedly a radio or firearm.

This assumption takes hold like wildfire; in no time, even the international media is circulating it.

Leftist militant or police infiltrator? Many pacifists were quick to label those fighting back during the eviction of the square on June 11 as paid police provocateurs. None of these allegations proved true.

Those at the barricade eventually have to retreat into the SDP office, and 70 people are arrested in a raid. Among them is Ulaş Bayraktaroğlu, identified in pictures clearly as one of the main people throwing the Molotovs: he’s a former political prisoner from the state-invented Revolutionary Headquarters case, and a member of the central committee of the SDP. The police also show a handgun they say was found among other weapons in the offices. The conspiracy theorists update their stories. Despite their determination to remain in denial, the pacifists involved in the Gezi Resistance are confronted with the fact that this movement also includes bona fide leftist militants, some of whom are involved in armed factions. So much for the spin doctors and liberal intellectuals who want to frame Gezi as Turkey’s version of Occupy, who hurry to label those who fight back as provocateurs.

All day and into the night, there is intense street fighting in and around the square, while inside Gezi Park a strange tranquility reigns. The calm is occasionally interrupted by medics rushing the injured from the streets into the medical area. From time to time, the police launch a barrage of tear gas into the park; some put on their gas masks so they can continue their conversations, while others rush to extinguish the canisters. In the end, the square is left to the police. All in all, it feels like another normal day at Gezi.

Enclaves of Militancy

One evening, I go to the neighborhood of Gazi, a stronghold of DHKP-C (The Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party—Front) and other leftist urban guerillas. The DHKP-C has come to resemble a death cult of martyrdom in their use of suicide bombers. Despite their undeniable ability to assassinate police, in their communiqué of support for the Gezi Resistance they said that they would not launch any attacks until absolutely necessary, as they want to see the street-fighting movement mature without such interventions. Hats off to them.

The fighting never stopped in the neighborhood of Gazi even when the reclaimed Gezi Park resembled a massive party behind barricades. Although only 19 kilometers away, Gazi is much further in class terms from the more white-collar resistance in Gezi, and has its own history and culture of resistance. A slum dating to the ’60s, it was the destination of many refugees from the Kurdish civil war, and it has always been a strong enclave of the leftist Alevi population of Istanbul.

In 1995, a paramilitary drive-by attack on two cafés and a bakery left an elderly man dead before the attackers fled to the local police station. It was a provocation in the true sense, not the kind alleged by pacifists at Gezi. After the vehicle rushed to the police station, neighbors immediately gathered in front of it, only to be fired upon with high-caliber machine guns. Another person died on the spot and many others were wounded.

Gazi exploded. For four days, it was in open revolt, with battles against the police and the army. In the end, seventeen people were killed and the rebellion was brutally crushed, but it left a deep mark.

Some Greek comrades who go to Gazi looking for that Aegean solidarity in the flame of a bottle say that they have never seen such large Molotovs. Indeed, every evening a march starts up on the main street and becomes an urban war with fireworks, stones, slingshots, and Molotovs directed against the police and their armored vehicles, met by tear gas and a plethora of explosives and projectiles. People from the neighborhood tell me that at times both sides have also fired upon each other, but no one has caught a bullet yet.

At Gezi Park, the Gazi neighborhood has become a mythical land where superhero leftists wage war on the pigs. It’s distant enough to be an Other inspiring admiration. This reminds me of how US liberals love it when the Third World riots against corrupt governments, yet line up to protect the police from angry youth in their own cities. The sentiment in Turkey is not as bad as in the US though—how could it be? When the police attack Gezi, people fantasize about Gazi coming to the rescue. As usual, Twitter is the venue for rumors: “Gazi neighborhood is on the highway marching to Taksim!” “The police are totally fucked now that Gazi is coming,” but the superheroes never arrive en masse.

That is, not until the last attack on the park on Saturday June 15. That day, thousands of residents from Gazi walked on the highway at night and fought their way to Taksim, finally reaching the city center by morning. They joined in with those attempting to take back the square; but even with their help, in the end, we could not recapture the square for a second time.

Counter-Insurgency

Tension reigned after the police took Taksim square on June 11. Everybody was waiting for the inevitable final battle. It was clear that the police had taken the square in order to prepare a staging ground from which to take back Gezi Park. Walking around the encampment, you could feel the urgency. Some were collecting the most valuable things to be rescued in case of a raid; others were preparing, filling balloons with a panoply of fire accelerants. The counter-insurgency strategy of the state was in full force: Erdoğan and his cronies kept emphasizing that naïve young environmentalists were becoming pawns in the hands of leftist terrorists, and that those who were behind all this unrest were actually the “interest lobby”6 or “foreign agents.”

The government used outright lies to rile up its base against the Gezi Resistance. The day after the park was reclaimed for the commune, on June 1, the heaviest fighting occurred in Beşiktaş, as the soccer fan club Carşı tried to make its way up the hill to reach Taksim. They fought for hours in their own neighborhood, in one instance hijacking a massive bulldozer to charge the police lines. When it seemed like the police were on the verge of committing a massacre, hundreds of people fled into a nearby mosque seeking shelter. The muezzin, who sings the call for prayer, let people into the mosque and facilitated the formation of a makeshift clinic. Blood was oozing from multiple head injuries and many were vomiting from the tear gas.

This episode was brought up over and over again by the AKP and Erdoğan himself to illustrate the sinful nature of the resistance. They had entered a mosque with their shoes! They were drinking beer and having orgies! People running for their lives had entered the mosque with their shoes on, but all that transpired inside was a frantic effort to stanch bleeding wounds. Such lies were refuted even by the officials of the mosque itself and served only to infuriate those who were involved in the protests.

The mosque of Valide Sultan is turned into a makeshift medical center treating people injured on the street.

Erdoğan’s strategy was to polarize the country by defaming the Gezi Resistance. He was counting on his 50% electoral victory, emphasizing his democratic ascension to power. Erdoğan became such a defender of democracy that when he was at his mildest, he would encourage the resistance movement to meet him at the polls in the upcoming elections. The possibility that those reclaiming Gezi and Taksim Square could be done with both the military—the brutal guardians of secular democracy—and with democracy itself, which brought autocratic neo-Islamism to power, was beyond the comprehension of those in power in Turkey. Where the experiment in autonomous self-organization will lead the rebels of Turkey is still uncertain, but the circumstances in which the struggle emerged point to a critique of democracy itself.

Meanwhile, the government was reading from the counter-insurgency playbook page by page. The AKP met with self-appointed representatives of the movement to seek concessions and prepare a pretext of failed negotiations. The commune rejected such representation outright, holding autonomous forums at seven different areas of the park to discuss how to move forward. The park was cleared while these discussions were still in their initial stages.

Although there were no “naïve environmentalists” at Gezi, there was a degree of naïve trust that the negotiations with the government could at least delay the impending attack. Consequently, the final attack came when people least expected it. The police attacked on June 15, when the park was filled with its usual evening crowd of children and the elderly. They entered Gezi Park, destroying everything and brutally beating everyone in their way. The city exploded once again, as neighborhoods started to make their way towards Taksim to participate in a battle that would last for more than a day.

Fighting for the Commune

There was something odd about the water cannon that evening, during the eviction of Gezi Park. Instead of spraying at the fiercest members of the resistance at the front, the nozzle was directed to spray over everyone. There was no tear gas launched at that moment, yet the air was acidic, burning in our lungs. Were they using transparent tear gas? Was it some new crowd control weapon?

It became clear what was happening when we saw people running into sympathetic bars, furiously stripping off their clothes soaked by the water cannon to reveal that their whole bodies were bright red. Some were convulsing, trying desperately to rub anti-acid solutions all over their skin. The next morning, the newspapers published photos of the pigs loading jugs of pepper-spray into the water cannons. The initial pepper spraying of the woman in the red dress had produced an iconic image of the resistance, which spread through social media. With no sense of irony, the police were now dousing the entire population in pepper spray from the nozzle of the water cannon.

The barricade wars went on until the first hours of the morning. After a few hours of sleep, we were back facing the tear gas and ripping up cobblestones on Sıraselviler, one of the streets that lead to Taksim. It was the usual back and forth as we advanced toward the water cannons, only to be sprayed back to our original position behind the barricades. It was Father’s day; some people had hung a banner for our patriarch sultan, reading “Happy Father’s Day, Dear Tayyip.”

Finally, the police overcame our barricades and there was panic as they charged down the street arresting people. I had the keys to a nearby apartment, so I gathered a group of fugitives who seemed helpless and lost and herded them into it. Eleven people around their mid-20s flooded into the apartment with relief. Peeking out the window, we saw a manhunt on the streets—plainclothes police were sweeping up everyone they found. The fugitives hadn’t forgotten their manners; they clumsily took off their shoes at the door even though I insisted that it didn’t matter under the circumstances. I was reminded of Erdoğan railing against the infidels who didn’t take off their shoes when they went to have their orgy at the mosque.

It was a bit awkward, as none of us really knew each other; there seemed to be three or four different groups in the tiny apartment. Everyone was riled up and speaking frantically about the events of the day and the weeks past. Suddenly, I realized that some of them were nationalists; others were upset about people throwing rocks at the police. This was the spirit of the Gezi Resistance: finding yourself in the same space with people you never thought you had anything in common with. I was tempted to argue with them, but after all the tear gas I didn’t have it in me. Later I lamented that missed opportunity.

After the police left, we went back out into the street. It was 9 pm; as on every other night over the past three weeks, people were leaning out of their windows banging on pots and pans. Cars were honking; some residents started chants from their windows as the pot banging subsided: “Shoulder to shoulder against fascism!” “No liberation alone, either all together or none of us!”

Night had fallen. We began converging on Istiklal Avenue. Once we were a few thousand, we started marching toward the square with the conviction that it belonged to us. The police attacked with tear gas and water cannons. How many times can you experience the same sequence of events and still find joy in the face of it? A group of young and fearless street fighters headed to the front with one of those boxes of fireworks intended to be placed on the ground and watched from a safe distance. They lit it up and held it aimed at the closest water cannon, advancing slowly as bright colors exploded on the line of cops. The crowd behind them applauded wildly as we advanced to reinforce the growing barricade before setting it on fire.

The battle continued into the early morning hours until there were not enough of us left in the street. We returned home wondering what would happen the next day, and what would happen to Turkey in the future.

This is Only the Beginning

Once the police cleared the park, they continued by raiding the homes and offices of the best-known participants. The first raids were predictable: the state went to the addresses of leftist militants and groups, as it had for decades. Dozens of operations took place and many of their cadres were arrested. In addition, there were raids targeting the leaders of Carşı, the soccer fan club of Beşiktaş, as well as those who tweeted under their legal names about what was happening in the streets.

The euphoria of the Gezi resistance hasn’t evaporated yet. The stories are on everyone’s lips; it’s all people talk about in the cafés and bars of Istiklal. During Pride Week, I attended some of the events; the theme this year was resistance. Both the trans march and the main Pride march were bigger than they had ever been: 50,000 people adorned in rainbows in the face of a traditionally homophobic Turkish society. Friends commented that this was probably the second time that there were more straight than gay people in the Gay Pride march—the first being thirteen years ago, when there were only a few dozen people, most of them allies marching in solidarity.

At the onset of the rebellion, there had been instances when anti-women, anti-sex worker, and homophobic chants could be heard in the streets. Queers and feminists intervened in various ways when this took place; they succeeded in countering this manifestation of patriarchy in a transformative way.

The story goes that during the first days of the uprising, after the police were kicked out of Taksim and the square was reclaimed for the people and barricaded, there was a moment of calm. A delegation of Carşı members took advantage of this to pay a visit to the offices of one of the main LGBT organizations in Turkey. Like other rebel identities and leftist groups, this organization also had an office in the liberated zone of Beyoğlu from which it was providing crucial infrastructural support to the uprising. Carşı entered to offer an apology for their homophobic and sexist chants. They explained that this was what they had been taught by society, but now they understood their mistake. As a token to show the sincerity of their apology, they had brought a shield that had previously belonged to the riot police.

After the dust settled, I met up with a friend I’d made during the heady days of the commune, a student from Kurdistan attending Istanbul Technical University for an engineering degree. We talked about the peace process the AKP had been crafting with the PKK since the winter. He was extremely cynical about the politicking, seeing the Gezi Resistance as the true path to peace for the Kurdish struggle. We exchanged stories we’d heard about personal transformation during the uprising. He told me about the tensions between their BDP tent, with the flags of Öcalan, and some of the Turkish nationalist elements in the Gezi occupation. That argument had become a dialogue that continued, interspersed with battles with the police, throughout the events. Suddenly finding themselves on the receiving end of state violence and a media blackout, many Turks had to come to grips with the fact that their perceptions of the war in Kurdistan had been mediated by the same corporations that were silencing them now.

Sharing this space of resistance against a common enemy inspired a revolutionary reconciliation. Yet with summer lethargy taking over, the first manifestation of the Gezi Spirit came to an end. June had left five dead and hundreds with serious injuries, some in critical condition. Physical and figurative wounds needed healing. Although from afar, it might seem that things have died down since June, on the ground there is a tense anticipation of what is to come. One challenge for the resistance will be the upcoming election cycles: municipal elections in spring 2014, and general elections a year later. All shapes and sizes of political leeches are looking to co-opt the movement.

It is incredible how the sense of nausea, helplessness, and depression that had overtaken many in the face of the steamroller of the AKP has evaporated after Gezi. It is still an open question how the Gezi Resistance will develop in the future and whether or not it will be able to further the practices first developed behind the barricades. Although one cannot predict the course of the coming years, it is unquestionable that a genie has come out of the bottle and millions have found each other. This spirit is haunting Turkey and the worst nightmares of those in power; everyone knows that Gezi will have a lasting impact on social and political life in Turkey. The Gezi Resistance is prepared for the long haul. As we reminded each other in one of the most popular chants:

This is only the beginning. Continue the struggle!

People working together to build barricades.

Further Readng

- Postcards from the Turkish Uprising

- The Roots of Turkish Fascism

- Understanding the Kurdish Resistance

-

Recently, DAF collapsed when it emerged that a couple at the center of the organization had been employing physical and emotional abuse towards members. ↩

-

A reference to the TV series Game of Thrones. ↩

-

The Incredible Hulk is detourned by replacing Hulk with Halk, the Turkish word for “the people.” ↩

-

The AKP has attacked the bustling street life in Beyoğlu by passing laws against alcohol consumption. ↩

-

One of Erdoğan’s initial remarks on the uprising was to call its participants çapulcu, looters or marauders. Participants assumed this name for themselves, proudly proclaiming that they were all çapulcus. ↩

-

We assume that Erdoğan meant to implicate the old-guard bourgeoisie with this epithet, but also to cultivate support among those who see interest as a sin in Islam. ↩