Born on December 9, 1842 into an aristocratic family in Tsarist Russia,1 Peter Kropotkin developed radical ideas in the course of his scientific research. In 1874, a few hours after he presented a well-received report regarding glacial formations to the Geographical Society, he was arrested and accused of subversive activity. The following narrative, derived from his own memoir and other historical documents, details his escape from a St. Petersburg prison two years later.

This is adapted from our forthcoming narrative history of anarchism; you can read another advance selection here. The above illustration is by Julian Watson from Kropotkin Escapes, a forgotten edition of Kropotkin’s account of his escape, currently being reprinted by Detritus Books. To learn more about anarchism, start here.

Peter Kropotkin.

The year 1876 arrives with wintry breath. Two years in the Tsar’s prisons have taken their toll on Peter Kropotkin. Though still in his early thirties, he has suffered scurvy, malnutrition, rheumatism, and a series of debilitating illnesses. Kropotkin’s brother has been exiled to Siberia; many of his fellow prisoners have died or lost their sanity, and he is approaching the end of his rope. Fearing that he too will die before his trial begins, the authorities transfer him to a hospital prison.

Here, with fresh air and a window that admits sunlight, he immediately begins to recover—if anything, too quickly, he fears. He takes great care to play the invalid so they don’t transfer him again.

One afternoon, a guard whispers magic words to him: “Ask to be taken out for a walk.”

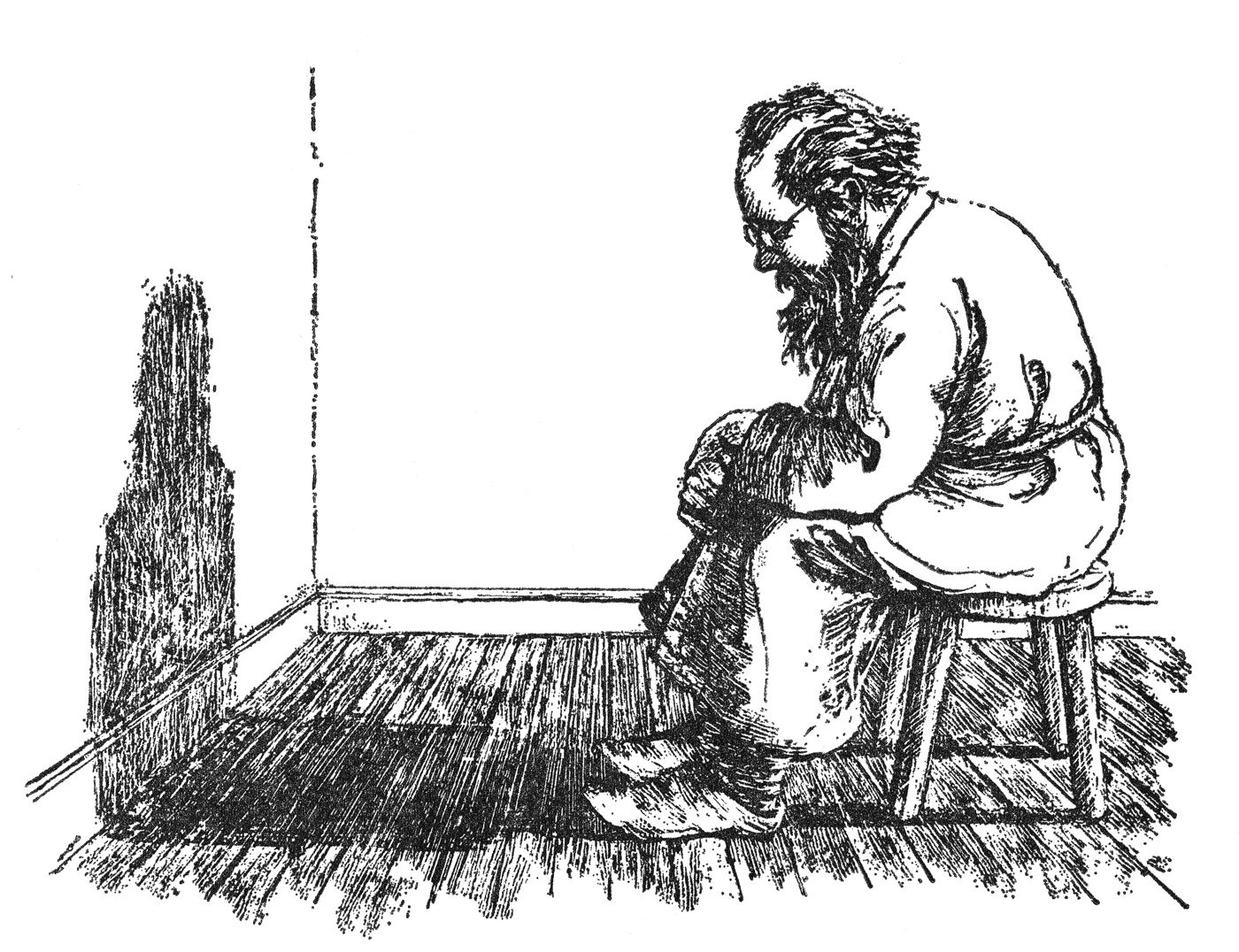

Peter Kropotkin exercising with a wooden stool in the Fortress of Peter and Paul before his transfer to the hospital prison. An illustration he drew himself.

The yard is three hundred paces long, and at the other end of it is a gate—an open gate. Beyond the sentry box, Kropotkin can see people and vehicles passing on the street.

He is permitted to walk back and forth in a line perpendicular to the yard. A sentry accompanies him, five paces away, always between him and the gate. However, as nothing wearies a healthy young man more than moving at a snail’s pace, the sentry often drifts a few steps ahead. With a mathematician’s eye, Kropotkin guesses that if he bolts at such a moment, the guard will run toward him, rather than ahead to block his path; thus, while he will travel in a straight line, his pursuer will have to move in an arc, and it might be possible to retain his lead.

When he returns to his cell, he can barely steady his hands to scratch out a message to smuggle to his comrades:

“This nearness of liberty makes me tremble as if I were in a fever. They took me out today in the yard; its gate was open, and no sentry near it…”

An illustration from the hand of Peter Kropotkin, showing him in the window of the prison.

The flannel dressing gown will not do: it drags on the ground, and he is forced to carry the lower part over his arm the way courtly ladies carry their trains. But his captors will not permit him any other garment.

Between visits from the guard, he practices throwing it off in two swift movements. The guard passes his door, glancing in to see Kropotkin lying in his sickbed; a moment later, Kropotkin is on his feet, whipping the gown over his head and casting it away; another moment, and he is back in the bed, wearing the gown, ready for the guard’s next pass.

The day comes—June 29, 1876. The signal is to be a single red balloon ascending into the sky. Kropotkin takes off his hat to show that he is ready; he hears the rumble of a carriage in the street and scans the horizon, heart pounding—but there is nothing, the sky remains empty. Finally, his time is up, and he is led back to his cell. Convinced that his comrades have been captured, he speculates gloomily that he will learn what happened from them when he is transferred back to the fortress to die.

In fact, on that morning, his friends had discovered that there was not a single red balloon for sale in all the markets of St. Petersburg. At length, they obtained an old one from a child, but it no longer flew. In desperation, they bought a red rubber ball and attempted to inflate it with hydrogen; but when they released it, it floated only a few feet up, stopped just short of the top of the courtyard wall, and drifted back down to them. Finally, they tied it to the top of a woman’s umbrella, and she walked back and forth on the street, holding the umbrella as high above her head as she could—but not high enough.

As it turned out, this was a stroke of luck. After Kropotkin’s walk was over, when the carriage departed along the route that would have been used for his escape, it was stopped short in traffic by a line of carts.

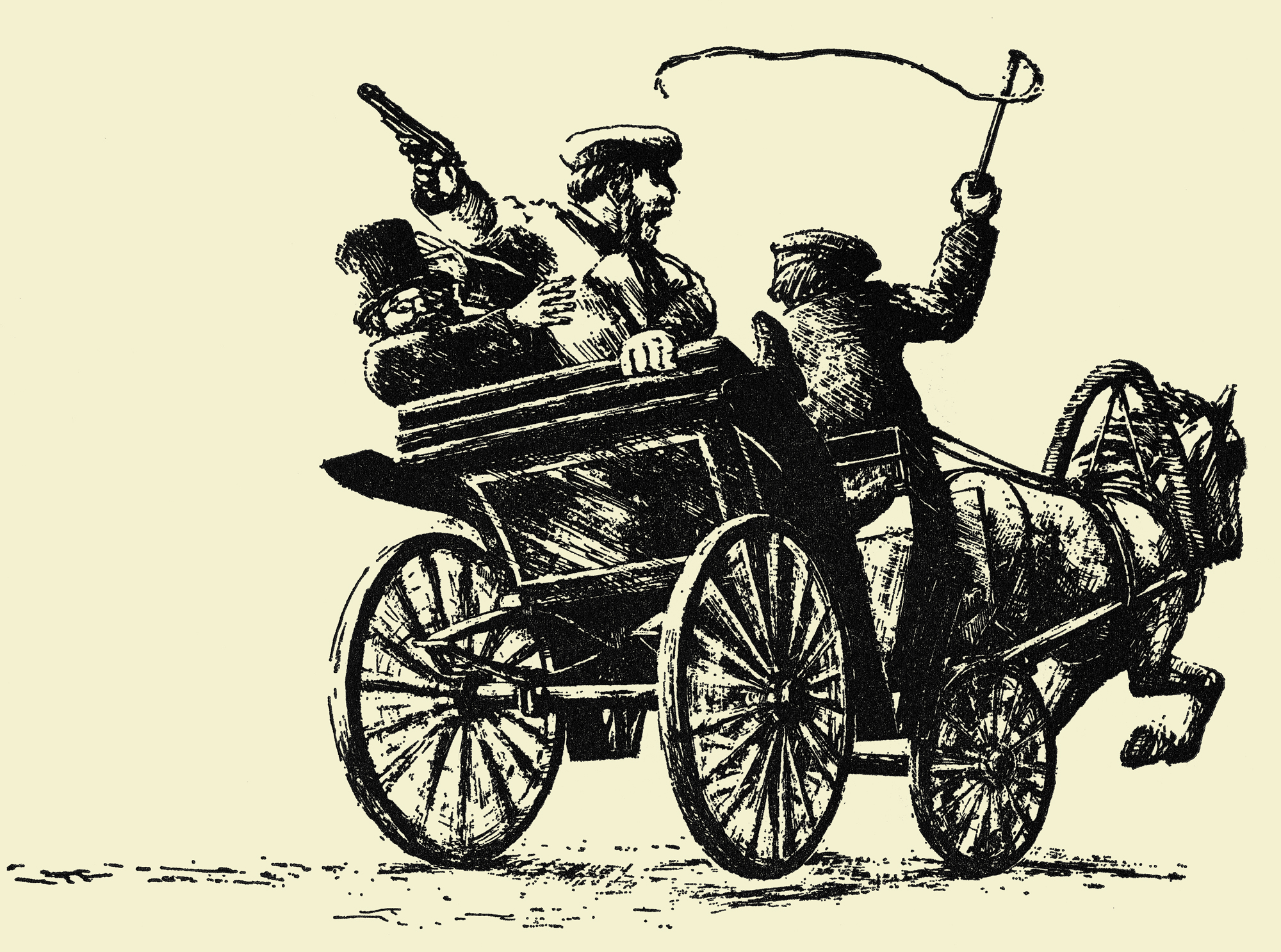

Another illustration by Julian Watson from Kropotkin Escapes, currently being reprinted by Detritus Books.

“A present from an admirer.” The guard passes a small watch through the bars. Kropotkin goes to the window to watch the woman departing unhurriedly toward the boulevard. If she is whom he thinks she is, she is risking her life by stepping within those walls.

He examines the watch. At first, it seems unremarkable; but when he pries the case open, there is a tiny scrap of paper pressed against the clockwork. His hands tremble again as he decodes the cipher.

Two hours later, Kropotkin is led out for his walk—perhaps the last before transfer. Again, he hears a carriage on the boulevard; again, he takes off his cap. On cue, a distant violin takes up a cheerful melody. His heart is racing as he shambles slowly along the footpath. He glances at the soldier, taking in the man’s powerful frame and the bayonet shining on the end of his rifle—and beyond him, across the yard, the open gate.

At the end of the path, he turns around; as usual, the soldier has drifted a few paces ahead. The time has come. He straightens his body and seizes the gown to throw it over his head—but the violin stops! He forces a cough and casts a furtive glance at the sentry, who is none the wiser.

A quarter of an hour passes. Time is running out. Finally, a line of carts enters the gate, one by one, parking at the other end of the yard.

The violinist resumes immediately, striking up a wild mazurka. Kropotkin shuffles again to the end of the path, terrified that the music will cease once more before he reaches it. When he turns around, he sees that his attendant has fallen several paces behind: the guard is facing away, contemplating the peasants unloading the carts. There will never be another chance like this.

A mazurka by Antoni Kątski [Anton de Kontski]. “Immediately, the violinist—a good one, I must say—began a wildly exciting mazurka from Kontski, as if to say, “Straight on now, — this is your time!” -Peter Kropotkin, Memoirs of a Revolutionary.

In a flash, the dressing gown is on the ground and he is sprinting across the grass. At first, he attempts to economize his strength, as it has been years since he has been able to run—but then the peasants drop their bundles and charge after him, shouting to attract the attention of the guard, who takes off in pursuit as well. Then he runs like a man possessed.

He hears the footsteps of the guard behind him, curses and panting as close as the pulse pounding in his ears. The soldier is swinging his bayonet, nearly grazing Kropotkin’s skin; were he not so close, he would undoubtedly fell the fugitive with a bullet. Yet the prince somehow keeps a single step ahead of him, and the two cross the entire field this way.

Another sentry is posted at the gate of the hospital, directly across from the waiting carriage. Kropotkin and his pursuers are charging right towards him, but he is engaged in furious argument with a seemingly drunken peasant about a certain parasite of the human body:

“And did you know what a tremendous tail it has?”

“What, man, a tail?” scoffs the soldier. “That’s enough of your tales!”

“It does, a tail! Under the microscope, it’s this big!” He stretches out his arms as Kropotkin, the soldier, and the peasants come storming through the gate in a mad procession.

An illustration by Kropoktin showing his escape from the hospital prison.

Ahead, Kropotkin sees the carriage, now only a leap and a bound away; but the coachman is facing away from him. Kropotkin almost shouts out his comrade’s name, then catches himself and claps his hands instead. The coachman glances around and immediately rouses his horse, crying out, “Get in, quick, quick!” Kropotkin’s foot is on the running board. His comrade is waving a revolver in the air: “Go, go! I’ll kill you, you bastards!”

“Stop them! Get them!” But the horse is already galloping down the boulevard. Kropotkin’s friend pushes an elegant overcoat and top hat into his hands. They take the first turn so sharply that the carriage almost turns on its side, but the two men throw themselves inward, righting it. They exchange a glance of disbelief.

Behind them, the gate of the prison is in an uproar. The officer of the guard has rushed out at the head of a detachment, but cannot regain his head to give orders. “Catch him! Chase him! Curse you, you imbeciles, I am ruined!” A man carrying a violin appears, asking everyone in turn what happened, who escaped, where he went, and what they think they will do. He takes special care to express his sympathy at length to the flustered officer. An old peasant woman in the crowd plays Cassandra: “They’re bound to make directly for Nevsky Prospekt. If you take these horses, you could easily intercept them.” No one pays her any mind.

An illustration by Peter Kropotkin, showing him escaping in the open carriage pulled by the horse Barbarian; two years later, Barbarian assisted Kropotkin’s friend Stepniak in escaping, as well, after Stepniak assassinated the chief of the Russian secret police.

Kropotkin and his comrade gallop all the way down Nevsky, finally pulling up at the Kornílov house. His sister-in-law is waiting there with Aleksandra Kornílova; they shave off the fugitive’s long beard and give him a change of clothes. Then Kropotkin and his comrade take a cab out to the Gulf of Finland, where they watch the sun setting through the open sky toward the island of Kronstadt.

Meanwhile, the police are raiding houses all over St. Petersburg in a desperate bid to recapture the escapee. They must find a place to hide out until it is late enough to go to the safe house. “How about Donon?” his partner suggests, naming the city’s most fashionable restaurant. “No one will think to look for you there!”

They sweep through a brightly lit hall crowded with high society and take the room reserved for private parties. Kropotkin’s comrades show up one by one, giddy and famished. This is the last time they will all be together.

The friends pass a joyous evening eating and drinking, telling old stories, and collapsing in laughter. “What, man, a tail?”

-

According to the Old Julian calendar employed in the Russian Empire at the time of Kropotkin’s birth, this date was reckoned November 27. Russia did not adjust its calendar to the one used in Western Europe until the Russian Revolution. ↩