Anarchists have observed May Day as a holiday celebrating revolutionary labor movements since 1886. Last year, anarchists around the world honored May Day despite the combined challenges of the pandemic and state-enforced lockdowns. Ahead of tomorrow’s May Day, we are publishing an analysis of what happened to the powerful labor unions of the mid-20th century, written from within one of them. This text first appeared fifteen years ago in the second issue of Rolling Thunder, our anarchist journal of dangerous living.

Since those days, the circumstances this text describes have only become worse, as one economic crisis has followed another while labor unions have struggled to respond. The combative unemployment that some young dropout anarchists chose as a strategy at the turn of the century has become, at some points, almost a generalized condition. At the same time, the political polarization of the white working class has rendered untenable some of the optimism with which the following text concludes—showing the cost of what happens when we miss opportunities to present revolutionary solutions to the problems engendered by capitalism. The reduction of the political spectrum to different flavors of centrist neoliberalism paved the way for nationalists like Trump to falsely represent themselves as “rebels” fighting “the elites” on behalf of the common people.

Today, when the working class has been divided into the remote, the precarious, and the unemployed, rather than focusing on a rearguard struggle to preserve the rapidly eroding economic positions and infrastructure of the previous century, we have to find new, dynamic ways to interrupt and overturn the capitalism economy as a whole. The price for not doing so will be a reaction even worse than the Trump regime.

For more on this subject, we recommend Work, our analysis of how capitalism has changed over the past century—and what it means to fight it today, especially in post-industrial areas.

RE: Report from the Shopfloor How Unions Lost Their Teeth

MEMO: How I spent my summer in the Midwest

TO: CRIMETHINC. HEADQUARTERS

FROM: AGENT 356592

The summer of the big AFL split, I infiltrated the federation by interning as an organizer for a certain dissident janitors union. The legends of past labor struggles were my introduction to anarchism as a youth, and I wanted to bring back some labor organizing skills to my southeastern town, which had been forgotten by virtually all unions. Today’s business unions generally follow a strategy of density: they focus on organizing areas where there is already a sizable Union presence, leaving historically un-unionized communities like my own to fend for themselves.

Thanks to this strategy, my internship took me to a Midwestern railroad town with a vibrant history of class struggle—though it seemed that much of that militant energy had been tamed by the time I arrived. The local I worked for had been established thirty years earlier, when some uppity janitors realized they didn’t have to be treated like dirt. Although the activity of the union had declined, the stories and pictures of picket lines, office occupations, and sabotage by janitors touched a soft spot in my heart, and I had high hopes.

Along with several other interns, I was part of one of two “surveying teams,” responsible for initiating contact with janitors and creating a database with information on possible union targets. The work itself was pretty simple, though in the course of gathering intelligence I quickly accrued enough counts of trespassing and breaking and entering to make even a seasoned CrimethInc. agent jealous. All this, and officially sanctioned dumpster diving! Imagine my delight at being knee deep in employee lists, invoices, and office memos instead of rotten produce and dumpster juice. A kid could get used to this.

We’ve traded death from starvation for death from boredom

The wealthy side of the city had seen the appearance of a lot of office buildings and corporate parks, most of which had not been documented by the union. These were not unionized buildings, yet obviously people were cleaning them. Who were they? It was up to us to solve this mystery.

I haven’t spent much time in office buildings, and seeing them from the outside I used to assume they were basically impenetrable catacombs of cubicles staffed by security guards and video cameras. Most of the ones I entered were not, as it turned out, and the ones that were were that much more fun. A couple of us would roll up to the security desk and start talking, making up some excuse or just chatting, trying to get information from the guard. While he was distracted, someone else would sneak into the building and try to find the janitors’ closets.

It’s one thing to distract a retail employee while your buddy slides something into her purse. It’s another to try to sneak by a fully-armed guard who hasn’t seen an exciting day on the job since that bag of popcorn caught fire in the microwave and set off all the sprinklers on the fourth floor. They take their jobs very seriously.

Yet it turns out it’s possible. I button my shirt, hold my breath, and go. Look straight ahead and just get on the elevator.

I only had a problem once, when the security guard saw me and told me to wait in the lobby. I disappeared up the stairs when he was distracted and had a heyday in the office, but when I came back down he was looking around for me and I had to hide behind a column. When I heard him talking to another guard, I bolted and didn’t look back.

At a fortress-like building, I pretended to smoke until an employee walked out the locked back door. She politely held it open for me and I got to work rummaging through the basement closets and pocketing some nice pens.

Except for my lack of a tie, I fit in fairly well at the offices. I got into character and became an up-and-coming intern for some insurance or telecommunications company. No one really minded when I asked questions or poked my head into the wrong door. No one could have recognized anyone outside of their immediate office anyway—capitalist alienation was on my side for once. To them, I was just another faceless drone aiming for the American Dream.

Janitors’ closets tend to be next to bathrooms or in other out-of-the-way places. In each building, I was looking for the name of the janitorial corporation that held sway there; I usually found these written on a trash can or on a container of cleaning chemical. There were about eight national or international cleaning companies operating in the area.

This worked for about half of the sites, but at the others we had to wait until nightfall to try to meet with the janitors themselves. The buildings were usually locked after 6 pm, but at corporate parks janitors might be found walking between buildings or taking out trash. In our expeditions, we discovered a trend that should not have been surprising: all the non-unionized janitors were Spanish-speaking Latinos. The local union staff didn’t have a single Spanish speaker—can you believe that?—so I attempted to speak using the very few Spanish words I knew (trabajo, durruti, syndicato, nada).

We had two Spanish-knowledgeable comrades on the intern staff, and they organized a meeting for Latino janitors in the area. Only a dozen or so came, and they reported being threatened by bosses if they attempted to work with the union. The communication barrier was embarrassing on the part of the union, as several of the work problems they raised could have been easily solved by a Spanish-speaking staffer. The local is working on the problem, and I hope they get things rolling soon.

The movement as a whole has been slow in responding to immigrants’ needs, especially as it has become entangled with nationalism and legalism and the drudgery that comes with being a mediating part of the status quo.

But it wasn’t always like this.

Our dreams will never fit in their contracts

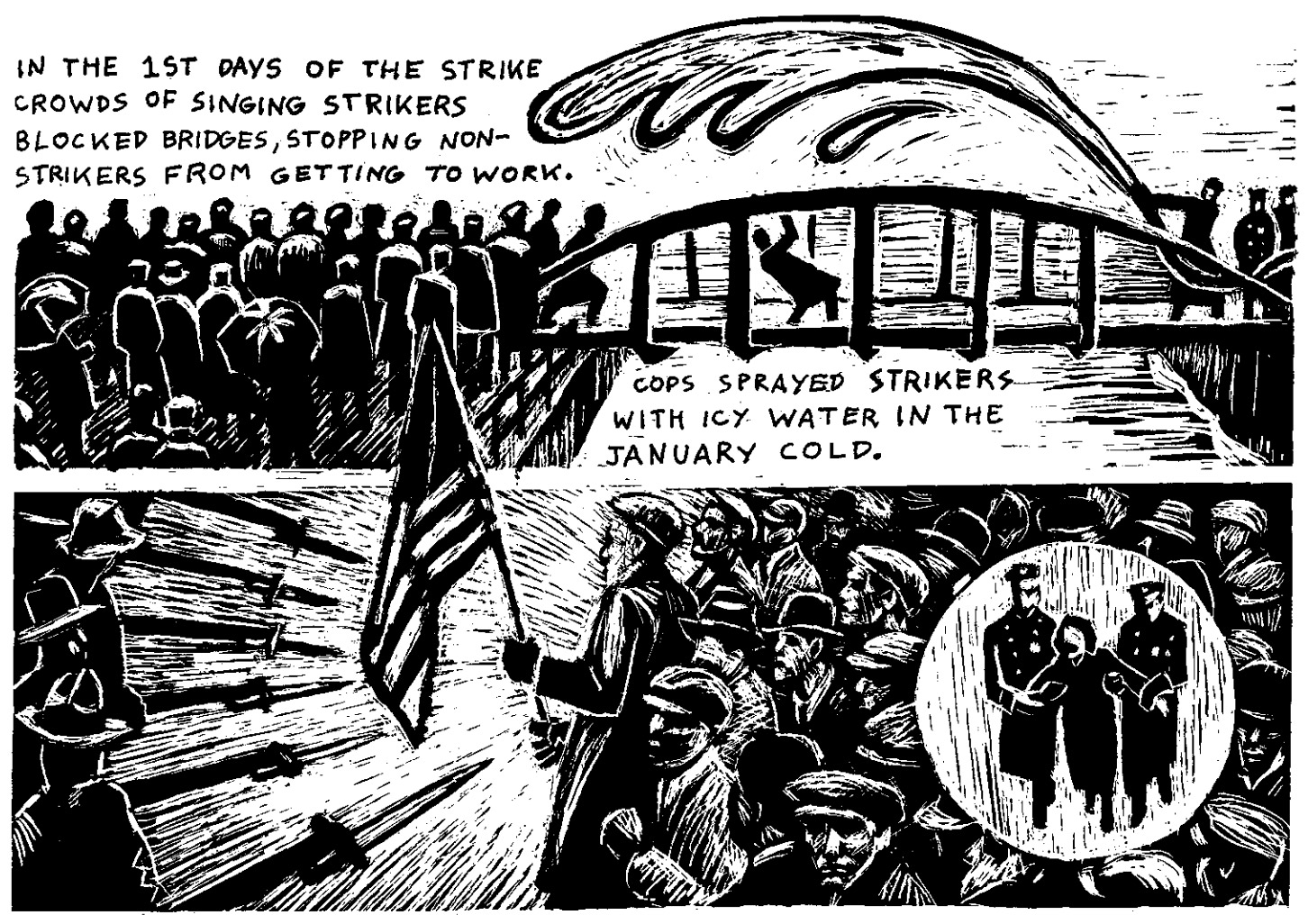

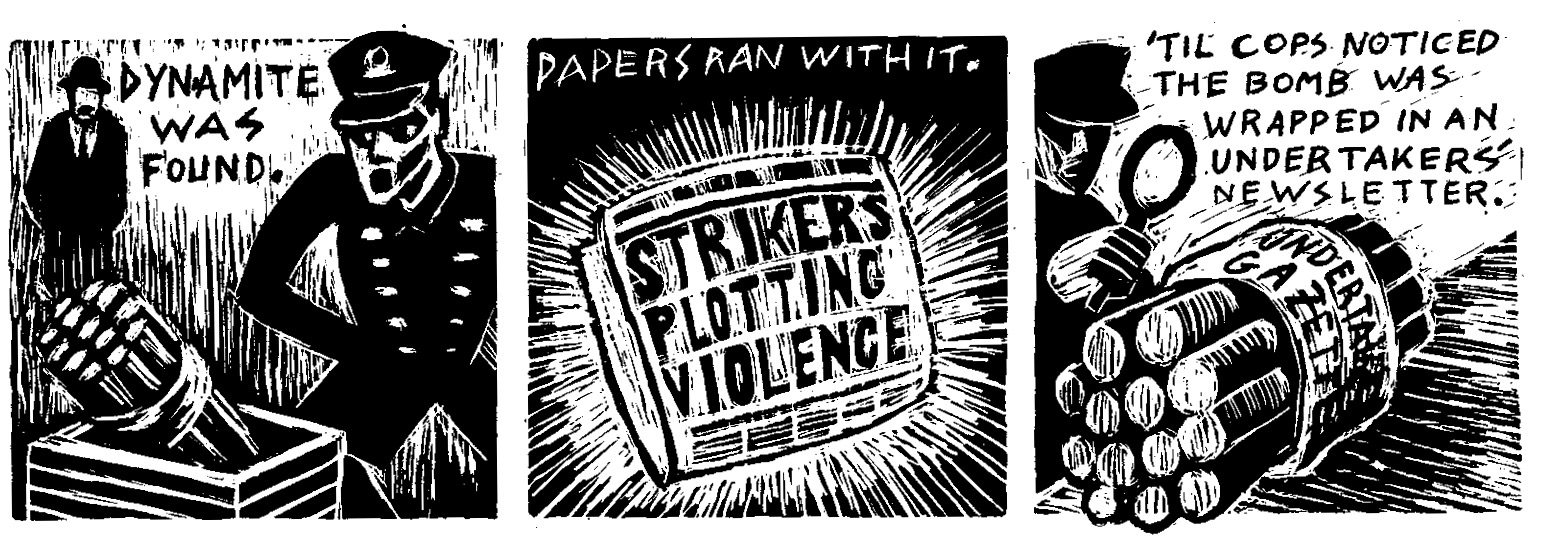

The labor movement was born and bred on sabotage as an illegal underground conspiracy of workers fighting to raise wages and improve working conditions by any means necessary. In the nineteenth century, disgruntled employees met by night and destroyed the wool and cotton mills threatening their livelihoods—to such an extent that “machine breaking” was made a capital offense in England. Early US labor agitators had to fear for their lives, as they were often chased out of town or lynched. Strikes crippled railroads and factories, cops and soldiers attacked picketing workers and families. It seemed the whole world might erupt in a global class war between the haves and have-nots.

Fearing industrial chaos, governments forced employers to yield to some of the workers’ demands. Workers’ movements were integral to the implementation of the eight hour day, safety and health regulations, and the National Labor Relations Act. The day had been won for the workers, and many on both sides of the class divide felt unions were on their way to redistributing wealth and power once and for all.

But in the course of all this, a funny thing happened. Unions themselves became legitimate players on the political playing field—with clout, bargaining power, and, most of all, healthy bank accounts. The struggles continued, but they began to have less heart. More money, but less heart. Business agents, grievance procedures, lobbyists, closed shops, dues check-off and “labor-friendly” politicians helped integrate—or entangle—unions into the smooth functioning of governments and economies, and it wasn’t much longer before they had become pale shadows of their former selves. Were unions still a tool for class war, or just glorified human resources departments?

To return to my summer—the stranglehold of legalization had choked the town’s labor movement years before, though many in the movement still showed a radical spirit. The president of my local, a jovial and warm-hearted long-time labor leader, reminisced over the occupation of a prominent downtown office tower and confided that one could seriously disrupt plumbing by flushing tied tampons down a toilet. This indicated not only willingness to be arrested, but also willingness to act without being arrested—an even more desirable trait—and his eyes lit up when I whispered to him some of my own adventures.

However, any direct action was relegated to war stories or video “action footage,” thanks to those bank accounts and laws making unions accountable for member action. The bosses can actually sue unions for illegal job actions. The unions are tamed; there is little discussion as to whether promoting a little sabotage is worth de-certification and bankruptcy.

The local had for a time cancelled union meetings because it seemed there simply was nothing to talk about—but with contract negotiations looming on the horizon, it was time to get into gear. At one of the first meetings I attended, a woman spoke up, saying that she had read the contract and that the union wasn’t for the worker, it was a tool for the bosses. The officers quickly countered that no, the union is for the workers and she needed to re-read the contract. The union is the workers, they said. The union is the workers, and the staff is just employed by the workers.

But over the course of the summer there was a subtle shift from the intern orientation, at which it was hammered into us that “the Union is the Workers,” to the confession on-site that the union is a business. Unions need money to run, and to get it, they are in the business of representing workers and handling grievances, and occasionally getting better wages and improving job conditions. The unions’ “strategic planning” can also be read as a business strategy: unions have to find areas where there is already a market for their product (the union); job sites with few employees won’t be able to repay in dues the cost of establishing the union, so those sites are ignored. On the other hand, organizing a factory of 200+ can get an agitator a position as a sort of business agent—then you’re “set for life,” I was told.

“The factory works because I do”

The local I worked for was well-established and had “union shop” contracts, according to which workers hired by certain employers were forced to join the union after a certain number of days of employment. In fact, the union didn’t even have to meet with the workers for them to sign up; their bosses gave them the union card and made them fill it out. This contributed to the union’s disconnection from its membership. Often, members didn’t even know they were in a union, or didn’t know what it did; and for that matter, the union didn’t keep track of its membership. The member lists we were supposed to use to call folks out for rallies were horribly out of date. But what did it matter? The dues were decided at the international level, not the local. The employers deducted dues from paychecks and sent a monthly lump sum.

Collaborating with the boss is good for business, and unions have gotten into the business of collaboration. I had a chance to look at the contract the woman was complaining about. The most disappointing aspect, as always, is the “No Strike/No Lockout” paragraph, which explains that the union cannot strike as long as the terms of the contract are followed. Even better, when there is a legal strike, the union pledges that it will send a “minimal staff” into the striking offices in order to keep them functioning—yes, the union will scab itself!

The union encountered some difficulties reining in its membership in preparation for the upcoming contract negotiations. The union wanted its members to want full-time status, but most of the part-time workers weren’t especially interested in changing. This was an example of a complaint I’ve heard often in my small southern town: the unions, people say, disregard their individual situations and force them to accept what the union says is “better for the whole.”

Though this critique tends to come from conservatives and is disregarded by leftists who think they can figure out what’s best for everyone, it has a certain radical undercurrent to it. Most unions have become large and bureaucratic, and their political and economic legitimacy is based on their ability to keep their members in line. The union knows what’s best; in order for negotiations to go well, your desires have to fit into a certain box so that the negotiators can squeeze them into an even smaller contract. The union has to be able to give the bosses a promise of stability, a guarantee of the security of the status quo and the smooth running of production. Otherwise, it’s out a customer.

As these unions are inextricably entrenched in the functioning of the economy, of course they’re more interested in the right to employment than the right to enjoyment. Business unions are about making sure that everyone wants the same thing, rather than the workers uniting and standing up together for their individual desires.

Consumption Unionism

There were pockets of dissatisfaction within the local, and at moments there seemed to be hope for change within the membership. But the members themselves had been beaten, both by the employers and by the union. One young man explained that the bosses had threatened to deal harshly with disrupters, and he was unwilling to stick his neck out on the job without the support of his co-workers—which was non-existent. Defeat, yet again.

Beyond the institutionalized constraints, the biggest roadblock to a vibrant union was the basic lack of a culture of solidarity. Folks didn’t stick up for one another against the boss. “Union” was just another deduction from wages, not something that existed in the relationships between workers on the job. What good was a union card if it sat idle in your back pocket? Credit cards, discount cards, membership cards. Unionism became just one more thing to consume in order to get a better job, participation optional.

This isn’t to say that legalized unions bring no benefits to the workers themselves. US unions pride themselves on raising the standard of living and creating a large middle class. Many unions have helped to bring at least some fragment of the American Dream™ to US families. But this has altogether neutralized these workers’ opposition to capitalism, and removed them from participation in social struggle. Middle class workers, thanks to and along with their unions, have been effectively domesticated.

Why struggle against capitalism, one might ask, if one has a working garbage disposal of one’s very own? It’s a question of values. The workers movement has always struggled for two things:

1) Autonomy, freedom, and power over the workplace and daily life; and

2) Wealth.

The bosses and politicians have ceded a fraction of their wealth but have not given up any power. Workers who might want to fight for more autonomy or power are held hostage by the middle-class lifestyle they already have; to strive for freedom would mean to risk their little hard-won comfort. Indignity at work is the price you have to pay to live the dream of two cars and a pile of debts.

Putting the “Work” back in “Ex-Worker”

Here, amid all this co-option and concession, I see opportunities for anarchist intervention and participation in the labor struggles of today. My home town, for example, as a place most unions have ignored, is a prime site for a renaissance of labor organizing without money, limitations, or institutions.

And outside our punk and activist ghettos, we dropout anarchists have a lot to offer. We’re used to living on next to nothing, so bosses can’t threaten us; if we can link up with others fed up with their power, we can threaten them. Our lust for freedom and autonomy, and our willingness to go without the consolation prizes of convenience, could help us develop new methods of cooperation and workplace action that no union today can even consider. We’ve acted outside formal structures for so many years that we take all the benefits of being able to do so for granted; in league with our fellow work-haters, we could open new avenues for genuine revolt. We’ve dumpstered meals for hundreds for our own conferences; let’s make sure there’s never a hungry belly at a picket line. Our infoshops and Food Not Bombs groups have given us good practice building community organs; let’s offer working parents daycare and free breakfast for their kids. And fun—fun is almost an ideology for most of us; let’s share our games and schemes and optimism with workers and co-workers, so that no one ever has to go home and waste away in front of the TV again. The togetherness that comes from those is exactly the foundation that makes collective resistance possible.

Us dropouts have a lot going for us that today’s union organizers don’t. Unlike most of them, we have no overhead. We can steal or scam what we need to fight with, squat or dumpster what we need to get by, and travel by rail or by thumb just as the I.W.W. union faithfuls used to. The money we raise for labor organizing can be put to better use than staff salaries or rental cars. As an intern with the established union, I still had to compute everything according to the scarcity logic of capitalism—from the pizza we ate to turning on the lights in the office, we were always reminded that we were spending or wasting our members’ hard-earned money. Organizers who don’t depend on dues for their livelihoods, on the other hand, can look at workers as real people and not just potential sources of income. Such union representatives could be collaborators against the bosses, not agents for them.

This isn’t to say we revolutionaries should spend all our time doing grunt work for the “real” labor movement. If we’re serious about this, we can make our own connections with grassroots labor militants and act on our own terms outside the bureaucratic institutions that have been holding the movement back. The formal labor movement still has plenty of organizers and members with radical visions and vibrant spirits, but perhaps we can do some things they want to but can’t: wheatpasting, visiting houses, smashing offices…

And this participation can go both ways: if we get involved in labor struggles, other labor activists will be more likely to join in ours. In the middle of the summer, I invited my fellow interns and the local staff to join in an anti-G8 solidarity rally organized by the regional Anarchist Action group. The union staff was excited to meet other potential allies, and the anarchist group was very interested in labor involvement, though the two hadn’t worked together before. After work, wearing our bright red union shirts and bearing dumpstered buckets for festive drumming, we joined in a parade that ended at the local Board of Trade. In the course of this unpermitted march, we were corralled, pepper sprayed, and beaten, but I was surprised and impressed by the willingness of the interns to stick through the action and not back down. Though short-lived, it was an exciting and inspiring few blocks in the streets, chanting class war slogans alongside the folks with whom I had taken my first meaningful steps into the class war.

Epilogue

Ironically enough, as I finish this report a strike has struck, of all places, right outside my home town. The company wants to cut pensions and jack up healthcare costs. The cement plants employ most of the people in the area, and only one of them is unionized. The other plants are watching—the bosses nervously, the workers excitedly. If the strikers get their demands, there’s a good chance there will be inspiration for the union to move into the other sites. And so, after all my ranting and raving against unions and their contracts and compromises, a few of us went down to hang out with the workers and bring lots and lots of dumpstered food. The picket is strong—every worker in this 100+ employee plant is off the job in this right-to-work1 state. Scabs are having trouble keeping up output: after a week, four customers have already stopped ordering. I got a chance to talk to the folks down there with their drawls, John Deere caps, Harley t-shirts, and, of course, sweet tea. They are sticking together and they all support the union. It’s inspiring to find another bastion of resistance in this once-hopeless humid town. I got some numbers, and we are going to keep in touch. They enjoyed the d.i.y. mashed potatoes and I promised to bring more. I didn’t talk anarchism on the picket line—I didn’t need to. They know what’s up. Every southern working class redneck knows she’s been abandoned by the politicians and that their bosses don’t care about them. The question is what we can do about this, together.

-

“Right to Work” is a euphemism for scab-friendly. ↩