Fundamental social change involves two intertwined processes. On the one hand, it means shutting down the mechanisms that impose disparities in power and access to resources; on the other hand, it involves creating infrastructures that distribute resources and power according to a different logic, weaving a new social fabric. While the movement for police abolition that burst into the public consciousness a month ago in Minneapolis has set new precedents for resistance, the mutual aid networks that have expanded around the world since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic point the way to a new model for social relations. The following report profiles three groups that coordinate mutual aid efforts in New York City—Woodbine, Take Back the Bronx, and Milk Crate Gardens—exploring their motivations and aspirations as well as the resources and forms of care they circulate.

This is the first installment in a series exploring mutual aid projects across the globe.

Food distribution at Woodbine, a social center in New York City.

With politicians such as Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez calling for the people to engage in mutual aid in order to survive the COVID-19 crisis, those not previously familiar with the term might never guess it was coined by an anarchist scientist who advocated against central government. As economies collapse and the institutions of state and capitalism fail to protect people’s health and livelihoods, communities have been left no choice but to rely on each other. This has led to a proliferation of spontaneous mutual aid networks in communities where none previously existed, often cohering around Facebook groups and Google documents.

Many communities, particularly those of poor and working class people, have long understood that we cannot rely on governments to meet our needs and have been providing for each other through autonomous grassroots collectives since well before anyone heard of the coronavirus. Now, the question is how to use the momentum of mutual aid’s recent popularity to transform the status quo and make these principles the basis for a new way of living together. An important first step will be to establish a clear distinction in the public consciousness between real mutual aid projects, which are founded on the principles of autonomy, horizontality, and solidarity, and initiatives that promote mutual aid in name only—those based more on a charity model, which serve to supplement and stabilize, rather than disrupt, state and capital.

In New York City, mutual aid networks have sprung up online since March in neighborhoods throughout the five boroughs. Existing mutual aid groups that have established deep roots in their communities, however, are in a unique position to meet people’s immediate needs and organize for long-term change in the midst of the current crises. The recent influx of enthusiasm and energy around this work, combined with our shared experience of disillusionment, anxiety, and rage, makes the unprecedented situation a potent crucible in which to build dual power.

Food distribution at Woodbine.

Since March, mutual aid initiatives already embedded in their NYC communities have adapted what they do and how they do it to the needs and limitations of our new reality. The organizers of Woodbine, a volunteer-run hub in Ridgewood, Queens “for developing the practices, skills, and tools needed to build autonomy,” have been building ties with their neighbors since they opened the doors of their community space on Woodbine Street in January 2014. The space has hosted weekly Sunday dinners since the following May, as well as poetry readings, clothing swaps, skillshares, seed exchanges, and a broad range of lectures and discussions on topics like the Rojava revolution and climate resilience. It has functioned as an organizing space for projects such as a community garden and a CSA where local residents purchase produce directly from independent farmers in the Hudson Valley. Having established space and infrastructure, as well as relationships with their neighbors in Ridgewood for six years, Woodbine has sprung into action as a relief hub over the past three months, sharing food, masks, and information with the community.

“Shortly after the pandemic started, we realized we weren’t going to be able to use the space as we normally would,” says Matt Peterson, one of the organizers of Woodbine. “But we still had the space, and the community and the people organizing with us, so it was clear that we had to turn it into a kind of mutual aid hub.”

When a local homeless outreach organization called Hungry Monk began operating an emergency food pantry out of Ridgewood’s Covenant Lutheran Church on March 10 to address the needs of those who have lost their income due to the citywide shutdown, several people from Woodbine began volunteering with them. They had the idea to collaborate with the organization by utilizing Woodbine as a satellite location for the food pantry; they now distribute free produce and prepared meals, which Hungry Monk receives from supermarkets and food rescue organizations, to their neighbors every Wednesday and Thursday at 10 am. Matt explains that they serve more than 300 people on each of these days; between their food distributions and the ones that Hungry Monk operates at the church on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays, they serve thousands of people a week. “They start lining up almost two hours before we open,” he says. “The lines are blocks long.”

Food distribution at Woodbine.

The two collaborating groups also offer home deliveries of food in Ridgewood and the surrounding neighborhoods of Glendale, Middle Village, Maspeth, and Bushwick for people who are unable to pick it up. This includes those experiencing symptoms, seniors, people with disabilities, as well as those who have young children they can’t bring with them to pick up food.

Since they started doing this, more than one hundred of Woodbine’s neighbors in Ridgewood have expressed interest in working with them. Because the group’s aim is not to be a humanitarian aid organization that merely fills the void left by failed government programs, but to build autonomy in Ridgewood, they are excited by the chance to collaborate in ways they weren’t able to before. In the coming months, they plan to hold in-depth conversations with their neighbors on how they can work together to meet other needs beyond food, such as education, childcare and housing. “We have to think about how to grow in scale in terms of meeting the needs of the neighborhood,” says Matt, “but also how to grow in scale in terms of our political visions.”

An important factor in generating so much new interest and support has been Woodbine’s dedication to making their work visible by posting about it on social media, writing essays, talking to the media, and, most recently, putting out a newsletter including analysis about how the neighborhood can self-organize at this critical moment. Their latest efforts with the food pantry have shone a light on the group’s history in the neighborhood. From the writings and videos on their website, local residents can see that the people in this space on Woodbine Street have been preparing for this kind of situation for quite some time. Matt also stresses the importance of showing up on a regular basis when laying the groundwork for a mutual aid network, and how the consistency of their twice-weekly food distributions has helped to solidify their relationship with the community. “I think it’s that kind of consistency that builds trust,” he says.

A group of Bronxites known as Take Back the Bronx have been consistent in their efforts to unite their neighborhoods in mutual aid since they formed out of the Occupy movement in 2011. Their deep roots in the area and the trust they have established with their neighbors have prepared them to respond to this latest disaster in ways that more spontaneous mutual aid networks might find difficult.

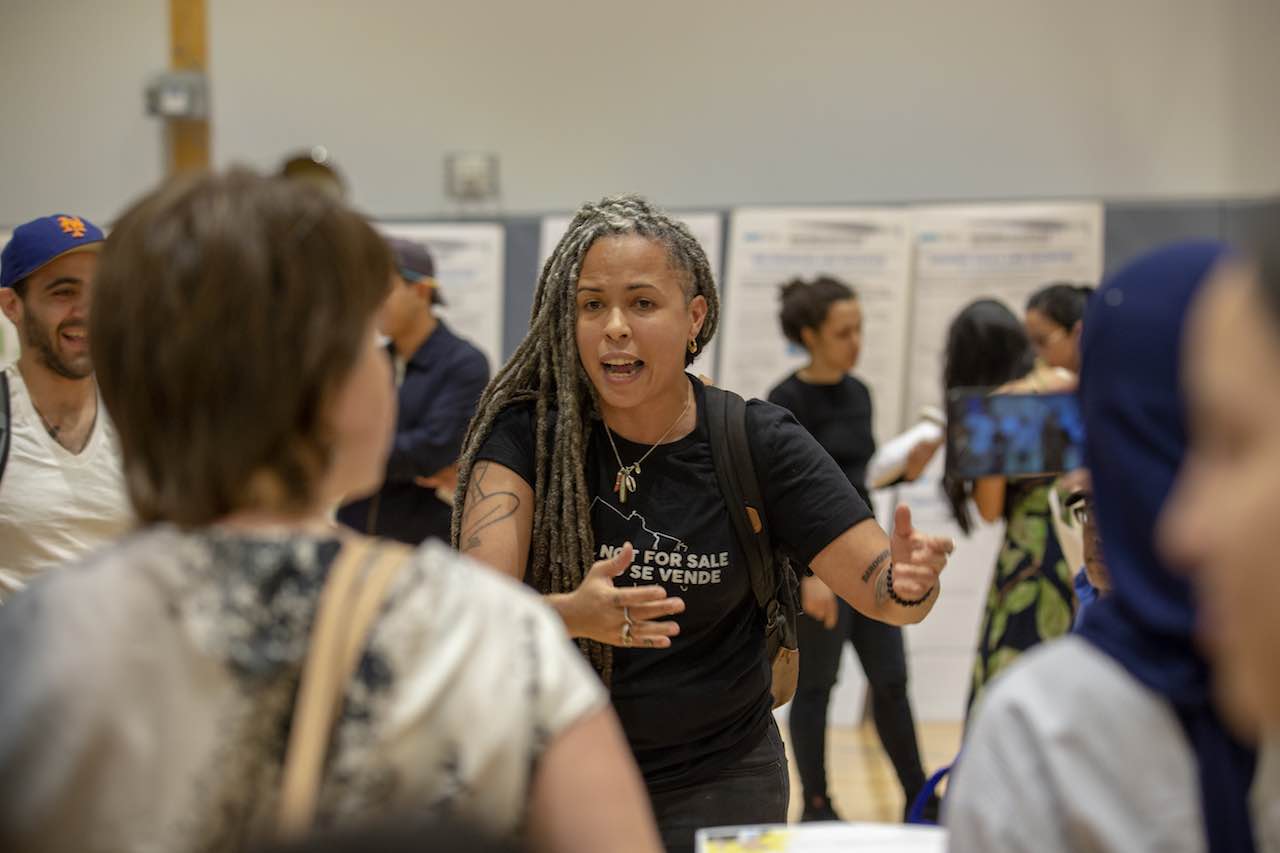

Shellyne Rodriguez of Take Back the Bronx at an open house in East Tremont on June 14, 2018 to confront city officials over the proposed rezoning of a part of the South Bronx. Photo from the Hunts Point Express.

Lisa recalls when the group changed their name from Occupy the Bronx. “We figured out early on that we didn’t want the word ‘occupy’ in our name, because we were already a community that was occupied,” she says. “It was a really good move, because it weeded out people that didn’t share our ideology.”

For TBBx, mutual aid is not just about meeting each other’s immediate needs—it’s also about building relationships between neighbors so they can fight together for their common interests. Currently, they have organized active rent strikes among the residents of three buildings, and plan to conduct a survey in the housing projects in Mott Haven, along with several doctors from Montefiore Medical Center, to ascertain what the tenants’ health needs are right now and how much access they have to medical care. They have also supported essential workers in demanding the personal protections their bosses aren’t providing for them. In addition, since their inception, they have protested police harassment and murder in their neighborhoods and organized against local politicians who promote gentrification.

https://twitter.com/AshAgony/status/1126656549915635713

The group builds the solidarity that is crucial to this kind of direct action through consistent mutual aid efforts such as their FTP project (Feed the People/Fuck the Police). Typically, they share hot meals with the community once a month at Hunts Point; they have recently adapted to the pandemic by switching to home deliveries of food. They include political literature in the bags they deliver, calling the recipients to discuss not only their needs, but also what the people receiving food can do to meet others’ needs, such as delivering food if they have a car, or calling people to let them know about the deliveries. The other purpose of these calls is to feel out where people are at politically and discuss what steps they can take to fight for systemic change together. “We know that in order to organize our communities, we need to meet people we’re they’re at,” says Lisa. “Because we are the people, we know what our needs are.” The food they share is donated by individuals within the community, some of whom share what they get from food pantries. “Contrary to popular belief,” says Lisa, “poor people give more than rich people do. We share what little we have.”

TBBx doesn’t take any donations from the government; they refuse to work with politicians, police, or nonprofit organizations. Their stated goal is for Bronx residents to gain autonomous control of their borough, a vision that includes cooperatively owned apartment buildings as well as the abolition of police, courts, and prisons. Lisa cites Indigenous communities like the Zapatistas as examples of people governing themselves. “I think we not only need to have a dialogue about it in a broader sense,” she says, “but let’s just try it. You learn by doing.”

https://twitter.com/TakeBackTheBX/status/1221577052119339015

Since the crisis began, people and groups already engaged in mutual aid have come together in solidarity to start new projects to empower their communities. One example of this is Milk Crate Gardens, a coalition of individuals and collectives with years of combined experience getting their hands in the dirt to promote food sovereignty and social justice throughout New York City. In March, Candace Thompson, founder of an urban foraging initiative called The Collaborative Urban Resilience Banquet, learned that the city was looking to clear out 2700 raised-bed gardens at JFK Airport, once part of the Terminal 5 Farm there. She and the others saw an opportunity to not only feed marginalized people in the current economic crisis, but to empower them to feed themselves now and in the future. They set up a Google form for requests and did their first distribution in early May, focusing on specific zip codes in Brooklyn and Queens. With the help of volunteers, they delivered the first 325 of these milk crates containing soil and seeds to people experiencing food insecurity, allowing them to grow their own food and medicine in their homes.

“We want to set them up for success,” says Luz Cruz, an organizer with the food/agriculture project Cuir Kitchen Brigade, one of the collectives that comprise Milk Crate Gardens. To ensure that the recipients have the knowledge they need to start on the path to food sovereignty, the group conducts skill shares on how to care for the plants as well as how to utilize the ones with medicinal benefits. Jacqueline Pilati, another coalition member who organizes the urban seed justice collective Reclaim Seed NYC, is creating a do-it-yourself video and zine as part of the project’s educational component. The coalition has also published a zine on urban agriculture.

Cuir Kitchen Brigade, a food project in New York City in solidarity with Puerto Rico’s sustainable agro-ecology movement, frontline communities affected by climate change, and individuals oppressed by political regimes. Photo from their website.

The motivating idea behind this project is that becoming more involved in our own food system, diminishing the need to go to the supermarket, creates a ripple effect of self-sufficiency that benefits us in more ways than just financially. “There’s a healing of trauma in taking responsibility for our lives and our beings,” says Luz.

When discussing the long-term potential for mutual aid in New York, Luz mentions that while not everyone involved in Milk Crate Gardens identifies specifically as anarchist, they have had very few issues with each other because of their shared dedication to creating radical change. Lisa of TBBx also believes cooperation between collectives will be vital to creating a new way of living from the devastation we are currently experiencing. “I think everything is about building relationships, strategizing and having political talks,” she says. “To have a revolution, everyone doesn’t have to be on the same plane, but you have to be ready to take action and fight together. It’s about finding the thread that binds us.”

One question for mutual aid networks to consider is how to harness the energy of the many people who now feel called to participate in this work, often looking for a kind of meaning and connection that was lacking in their day-to-day lives before—an experience that is all too pervasive in dense yet alienating cities like New York. At Woodbine, they are now considering how they can create a long-term organizational framework out of this very localized network of neighbors who have recently expressed interest in participating. Matt believes a key factor in building dual power will be outreach, which includes talking to people, fliering, and learning about the situations of their neighbors and how they can collaborate to meet each other’s needs.

Food distribution at Woodbine.

A belief in the importance of physical infrastructure in building autonomy and community resilience was what motivated members of Woodbine to establish themselves in their current home in Ridgewood six years ago. Having seen how Hurricane Sandy devastated New York City, they were convinced that holding physical space would be essential to responding to future disasters, an idea that has certainly been borne out in the upheaval of the past three months. One thing they have suggested could be helpful right now is utilizing spaces that aren’t being used, such as storefronts, as hubs for mutual aid and for organizing mass actions such as strikes and occupations. Matt believes this can be accomplished without force by building relationships. “People will have to self-organize wherever they are, to understand if there are needs for additional spaces they don’t already have,” he says.

About the recent swell of interest in mutual aid, Lisa says, “I try to be an optimist and a realist. We’ve been able to keep connections with people because they are sitting home more. Because it’s such a dire situation, people have welcomed the dialogue and the outreach more so than before. People are tired of sitting at home watching Netflix, being scared about what’s gonna happen after things are lifted and we’ve really got to pay rent. They’re looking forward to some change, and we’re saying, ‘That’s possible. Do you want to get down with this?’ We’ve been saying it all along.”

Perhaps the most important thing these groups demonstrate is that building a mutual aid network takes time, patience, and a dedication to developing solid relationships with one’s neighbors—a process that many of us, particularly city dwellers, have to relearn or learn for the first time. Our willingness to do so will help to determine whether mutual aid can become more than just a trend on the scale of our society as a whole.

“It isn’t new, but it is normal,” says Lisa. “This is the way that we are supposed to be living.”