For ten years now, we have observed April 15 as Steal Something from Work Day. Coinciding with tax day—when the government robs workers of a portion of their earnings to fund the police, the military, and various welfare programs for the ultra-rich—Steal Something from Work Day celebrates the creativity of workers who take a swipe at the economy that exploits them.

Yet today, the consequences of the global rip-off called capitalism have gone so far that nearly a quarter of us have no employment or source of income whatsoever. Many of those who still have jobs are being forced to risk death on a daily basis just to bring home a paycheck, while more privileged workers have seen their jobs invade their very homes. Tax day is pushed back to July—it’s difficult to rob those who have no income, though our oppressors aim to squeeze it out of us sooner or later.

The crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic should put things in proportion. While executives and loss prevention experts wring their hands about workplace theft, sticky-fingered employees are not the ones responsible for systematically draining resources from hospitals or accelerating catastrophic climate change. It’s not stealing from work that is outrageous—the outrageous thing is how much capitalism has stolen from us.

But How Do We Steal from Work in a Pandemic?

As history accelerates, the humble little gesture of workplace theft, via which so many workers have asserted their autonomy and made ends meet, has almost become outmoded. In a global disaster that is just a taste of things to come, we have to become more ambitious about what we aim to seize.

“Essential” Workers

The workforce has been divided into “essential” workers, “remote” workers, and the unemployed. In many cases, “essential” simply means “disposable”—along with doctors and nurses, it describes a range of low-paid jobs that involve a high risk of exposure to COVID-19. Of course, if you are working one of these jobs, you still have access to material goods; you can still steal from a grocery store or warehouse.

When so many people have no access to resources whatsoever—while employers and the politicians above them are conspiring to force us to risk a million deaths to re-start the economy—stealing to support those who cannot buy products becomes a solemn duty to humanity.

What can “essential workers” do besides sneaking food, medical supplies, and cleaning products out of workplaces? Can we set our sights on something more systematic?

Last month, facing layoffs, General Electric employees demanded to be kept on to build ventilators for the treatment of COVID-19. This points to the possibilities for workers to steal back their entire workplaces. Yet making demands of corporations like General Electric will produce few results unless we are able to find ways to exert leverage on them.

In Greece, unpaid workers in Thessaloniki went further, seizing the factory they had worked in and using it to manufacture their own line of ecological cleaning supplies. This is an example of workplace theft writ large, one we can aspire to emulate in the United States over the coming years.

Could we steal the existing infrastructure and use it to produce a different society? Should we aspire to take over the global supply chain and run it more efficiently than its current overlords do?

The quintessential 21st century work environment is the Amazon warehouse. Surveillance devices and software force humans to behave like robots. In some Amazon warehouses, gigantic screens display footage of employees who were caught stealing to terrorize workers into obedience. Cashing in on the pandemic, Amazon has added over 100,000 new positions, but all the profits are still concentrating at the top. Signs in Amazon warehouses instruct workers to remain three feet apart at all times as an anti-viral measure, when their work stations are actually two feet apart. Is there a place for such places in our dreams of the future?

Before we decide what aspects of the global supply chain to keep, let’s look closer at the meaning of the word “essential.” Police in some parts of the US have explicitly stated that “protesting is not listed as an essential function”; they aim to take advantage of the pandemic to suppress any dissent, though dissent is the only means by which we can assert our needs and defend our safety. Freedom is inessential, along with the lives of frontline workers. Meanwhile, the governor of Florida has deemed professional wrestling an essential function along with all other “professional sports and media production[s] with a national audience.” As in ancient Rome, what is essential is bread and circuses.

So we should not accept the concept of “essential workers” at face value. Capitalism has monopolized activities like food production that used to take place on a more decentralized basis. We are among the first human beings to be born into a society in which the only way to obtain food is to go to a grocery store staffed by employees. Most of us have no other option today; this monopoly is what makes grocery store workers “essential.” In almost any other model, these workers wouldn’t be the only line between us and starvation.

On a fundamental level, Amazon warehouses and corporate grocery store chains are like police: they are essential to the maintenance of this social order, but they are not necessarily essential to life itself. We depend upon them because—through centuries of successive enclosures of the commons—we have been robbed of everything that sustained our species through the first million years of our existence.

When we are thinking about how to steal our lives back from work, this suggests another point of departure, alongside individual workplace theft and collective workplace occupations. We can begin to re-establish means of subsistence outside the economy—for example, via occupied urban and suburban gardens. Especially for those who are now unemployed, this is a way to steal the possibility of subsistence from a world optimized for employment alone. Perhaps, one day, where there are currently Amazon fulfillment centers, there can be community gardens complete with collective dining areas and childcare bungalows.

Remote Workers

In the age of surveillance technology, some of the differences are eroding between warehouse workers who are monitored by drones and white-collar workers who are monitored by technologies that take screenshots at random throughout the workday. All of us are being “optimized” according to capitalist control mechanisms and criteria. In remote or “smart” working, our employers invade our bedrooms, ruthlessly fixing our most intimate activities to the demands of the market. Middle-class workers have to worry about whether the décor of our bedrooms and the behavior of our children will be acceptable to our employers. Nothing is sacred.

Camera-bearing drones maintain surveillance inside warehouses, just as the camera on the device you are using to read this article can be used to surveil you.

At the same time, as more and more of our lives become dependent on digital technologies, some of the differences between the employed and the unemployed are also eroding. Among those of us who are unemployed, many of us also spend our days in Zoom meetings and clicking around on phones and computers. Our behaviors—paid or not—can be almost identical. Our online activity continues to provide income to corporations employing a profit model based on the attention economy, harvesting data, and the like.

Presciently, for Steal Something from Work Day 2013, one of our authors analyzed the ways that time theft alone can fail to take us beyond the regimes of capitalism:

Workers who engage in tactics of la perruque [i.e., time theft], but use the reclaimed hours to participate in a digital capitalism that commodifies user attention, merely sneak from one job to do another. In 2013, we call it “social media”—in thirty years, it will have no name. […] We add stars and comments to Amazon products improving their sales; we self-surveil with Facebook; and we help search engines anticipate human desires by performing as a human test audience for them.

So while time theft is the one ostensible remaining means of stealing something from work for an entire social class now under de facto house arrest, we should not assume that it will suffice to get us beyond the logic we are trying to escape. That goes for the unemployed as well as for those working remotely.

What is the solution? To return to the wisdom of our forebears, we should never use any tool produced by the capitalist system for its intended purpose. To quote “Deserting the Digital Utopia,”1

“There is an invisible world connected at the handle to every tool—use the tool as it is intended, and it fits you to the mold of all who do the same; disconnect the tool from that world, and you can set out to chart others.”

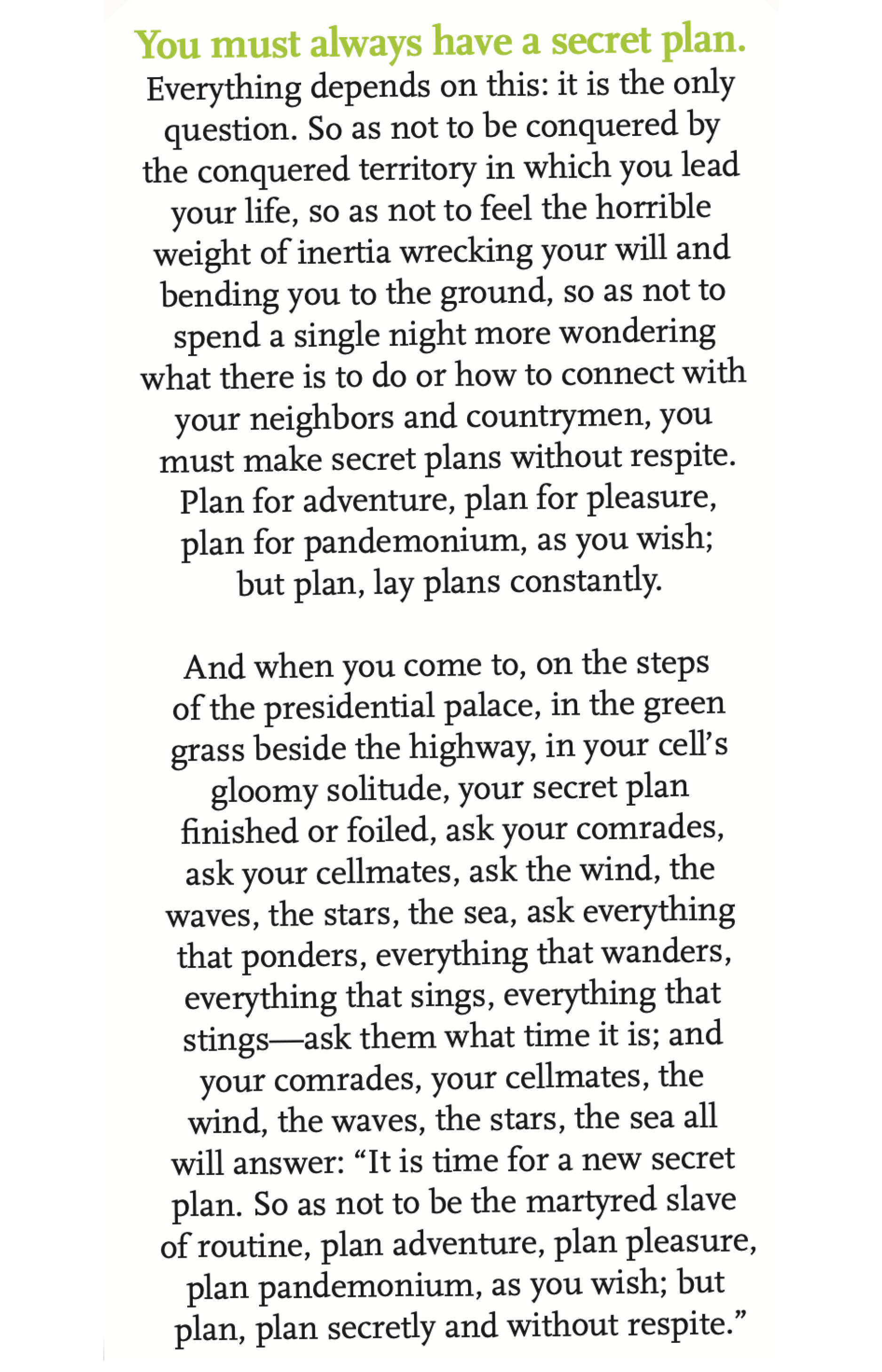

For those confined to working or playing online from home, this offers a way to think about our little individual revolts. When you are engaging in time theft, don’t just click around on the internet, delivering additional information to the corporations and governments that are spying on all of us. We have to use this time creatively and effectively to prepare for the next phase of global collapse. Teach yourself a skill that you can use away from the computer, something that can help you heal or nourish people, whether biologically or psychologically. Create new connections and networks that can assume an untraceable offline form in the near future. Print out letters and deliver them to all the tenants around you inviting them to participate in the unfolding rent strike and offering them support. Remember, you must always have a secret plan.

Now more than ever, stealing something from work has to mean assaulting the system that forces work on us in the first place.

We conclude with one employee’s narrative of a lifetime of workplace theft, a memoir of a simpler time when it was easier for many people to channel resources from the capitalist economy into joyous anti-capitalist creative activity. If the pandemic, automation, and surveillance technologies continue to transform our lives in the ways they have been, such stories may soon belong only to a comparatively idyllic past—but that only makes it more important to pass them on, so those who come after us can see everything that they have lost and whet their appetites to fight harder.

Time is Always the Best Thing to Steal from Work

I’m writing this on company time under stay-at-home orders.

I want to share an incomplete list of all of the things I’ve stolen from work over the course of my two and half decades as part of the work force. I want to start by acknowledging that my situation is likely different than yours. When and where we grew up, where we are living now. The kind of work we do. The relative privilege that each of us benefits from.

This is not a prescription or playbook. You might have access to opportunities I have not. The time and place and situation may be different, but the bosses are still the bosses and the fight is still the fight. Look for the cracks and squeeze through them.

Paper Delivery

When I was in junior high school, I had a paper route. I delivered the paper every day after school. Once a week, there was a coupon day. An extra stack of little papers arrived at my house with the bundle of newspapers. I was supposed to stuff these coupons into all the newspapers before delivering them. I was a good kid. At the beginning, I did what I was supposed to. It made the load of papers in my satchel weigh twice as much.

Still, I couldn’t help suspecting that most people didn’t care about the coupons. So I performed an experiment. I stopped stuffing the paper with coupons and waited to hear who complained. I made a mental list of the few houses at which people really wanted the coupons. I’d include the coupons in the papers I delivered to those houses. All the rest of them went straight into the recycle bin.

This saved me a literal weight off of my shoulders. It also freed up an extra hour of precious post-school daylight hours to play with neighborhood friends. The paper route was supposed to teach me the value of a job well done—and it did.

High School Tech Support

In high school, I was in a computer class. We students had free rein to use whatever we wanted, as long as we did tech support for teachers who were having issues. Jammed printer. Dead network. Missing mouse. We would come fix it.

Most of the time, though, I was in the corner using the high-speed audiocassette dubbing machine. It could transfer one tape to three others at the same time, at four times normal speed. I started a little do-it-yourself record label using that machine. This changed my life, connecting me to other young people around the world in the days when the internet was just getting off the ground.

I also designed, printed, and mass-produced countless zines on those high school computers, printers, and copiers.

Pool Admissions Desk and Concession Stand

Around the same time, I worked in a concession stand at a fancy pool serving upscale neighborhoods. I made minimum wage. I never paid for nachos or slushees, and neither did my coworkers, friends, or casual acquaintances.

In subsequent years, I also worked at the admissions desk. I operated the cash register. People who came to swim paid me and went on their way. Dollar fifty for kids. Two dollars for adults. Fifty cents extra for the water slide. All day. Over and over.

On hot summer days, the pool brought in several hundreds of dollars per day. Some days, a group would come in from a day care or camp. Those were big days.

It’s hard to skim off the top of a $1.50 charge. If you’re keeping the change, your pockets get heavy and jingly. There’s also a paper trail of receipts.

But not if the cash register is broken. Weirdly, every summer I worked there, the cash register would stop working the first or second week. In effect, this reduced the cash register to a money drawer, abolishing the paper trail of receipts. I would do the math in my head, pop the drawer open, make change, and keep a running count in my head. How many customers have come through the door today? How much can I skim without anyone noticing?

The answer: I bought a new computer, printer, monitor, and scanner to take with me to college. And a lot of records!

Learning to do math in your head can be an important skill if you weren’t born with a silver spoon under your tongue.

Grocery Store

Every shift during my lunch break, I’d wander over to the juice aisle, pick out a bottle, then go to the hot foods bar and heap up a pile of French fries. If my friend was working the hot foods register, we talk for a bit, putting on a little performance for any potential spectators. If not, I’d just go sit down and start eating.

As a cashier, I had a lot of discretion and prerogative. If something didn’t ring up properly, or lacked a barcode, or neither I nor the customer knew the produce code… they got it for free. Or, if I didn’t get the feeling that they were down, I’d ring it up for twenty-five cents. That way, they still saw me ring up something and weren’t forced to make a decision about the ethics of workplace theft.

Any time friends came through my checkout line, I pantomimed ringing up their groceries, turning each so the barcode was facing up, away from the scanner. I’d say “boop” out loud with my voice. We’d share a nod, a wink. Then I’d ask them to buy me a pack of gum. Total bill: twenty-five cents.

Once, I made the mistake of trying to pass along those savings to my best friend’s dad. He was pretty cool on most accounts. For example, during Sunday church, rather than making them listen to sermons, he taught his kids algebra and other math that was advanced for their respective ages.

But on this day, I grossly misread his sense of ethics. When he noticed that I was scanning items upside down, he started making a stink, raising his voice about his principles. Luckily, I was able to recover the situation before anyone figured out what was going on.

I was the slyest employee thief when taking food off the shelf; I always left with something tucked down my pants. A meal or two to tide me over from one shift to the next.

I also stole pantloads of film, processing, and prints. I would drop off a few rolls of photos from punk rock shows at the film developing desk, checking the boxes for all the upgrades: oversized prints, duplicates, fancy finish. When I picked them up, I’d say I had some other shopping to do before checking out. They just let me walk away with them. I never once paid for film, processing, or prints there. The good ol’ days.

College Computer Lab

In college, I worked in the computer lab. The university had a really fancy computer sitting unused in storage. I took all its internal parts home with me one by one. Later, I bought a case and reassembled them into a new computer to serve the general public in a shared computer lab at a DIY collective space.

Like many other things, stealing from work was easier in the 1990s.

Web Design Internship

It turned out I was good at web design. I’d crank out the work really quickly, then spend the rest of the time designing zines and working on other creative projects.

Every Computer-Focused Office Job

I have always stolen time from office jobs. It was especially useful to be good at keyboard shortcuts in order to hide or destroy whatever I was up to when the bosses came around.

I also took all the normal office things: cables, paper, printouts, photocopies, staplers, staples, tape, keyboards, mice, laptop stands, chairs. I’ve stolen a few computers from jobs. Once, I traded a couple such computers for a car that I then drove around the country on a Great American Road Trip.

When it’s provided, I always load up on food. Snacks for myself now, snacks for myself later when I’m not in the office. If friends come visit me at work, they eat for free, too, but they should also load up their bags and pockets. I try to make a point of using office-provided food to channel meals, snacks, and drinks to the houseless.

In the Time of Global Pandemic

This trip down memoir lane is all fine and good, even if some of the particulars aren’t necessarily useful anymore. But what does it mean to steal something from work when many people are working from home or out of work entirely?

If you still have a job at a physical place and still have access to physical stuff, you can continue to steal. Food, supplies… toilet paper! Take some for yourself, for your friends and family, for your mutual aid network. Don’t just hoard it—everything you pass on to those in need will be returned to you fourfold.

You can also steal for others so that they don’t have to. Do it without them knowing, if you think knowing might make them anxious. Cashiers still have the prerogative to selectively miss ringing up items for customers buying supplies during the pandemic. People loading bags of food for delivery can slip in an extra of this or that.

If your workplace is now your living room couch, dining room table, or bedroom, there are still ways you can steal something from work.

If you’re lucky enough to have “unlimited” paid time off (PTO), then for goodness’ sake, take paid time off! Use it to focus on your physical and mental health. Use it to care for your friends and neighbors. Use it to volunteer in mutual aid projects.

If you have flexibility to take some time away from the computer while on the clock, do it! Even if you don’t actually go anywhere, just step away from the computer for a while.

You can steal time.

You can take time during your workday, between Zoom meetings and Slack channel discussions, to do whatever you want. You can put some time on your calendar as “quiet working hours” to protect your calendar from meeting invitations. You can watch movies, educate yourself, or even write an article for an anarchist website about stealing from work! If you need it, take a nap or stare out the window.

It’s OK not to be productive™ in this situation. This time is not simply working remotely. We are working remotely during a global pandemic that has already killed over 100,000 people, an ongoing fascist takeover, and large-scale economic failure. You have permission to forgive yourself for not writing the next King Lear, discovering the next calculus, learning another language, or mastering a musical instrument.

If you want to do these things, you should. If not, that’s OK too. Just take care of yourself out there. Remember, your time is the most valuable non-renewable resource that you’ll ever have.

If your heart is free, the time you spend is liberated territory. Defend it!

-

The text continues, “The ideal capitalist product would derive its value from the ceaseless unpaid labor of the entire human race. We would be dispensable; it would be indispensable. It would integrate all human activity into a single unified terrain, accessible only via additional corporate products, in which sweatshop and marketplace merged.” Now we are seeing sweatshop, office, and even bedroom merged. ↩